Nana (echos)

Phthora nana (Medieval Greek φθορά νανὰ) is one of the ten modes of the Hagiopolitan Octoechos consisting of 8 diatonic echoi and two additional phthorai. It is used in different traditions of Orthodox chant until today (→ Neobyzantine Octoechos). The name "nana" is taken from the syllables (written in ligatures "ʅʅ") sung during the intonation which precedes a melody composed in this mode. The name "phthora" derived from the verb φθείρω and means "destroy" or "corrupt". It was usually referred to the diatonic genus of the eight mode system and as a sign used in Byzantine chant notation it indicated a "change to another genus" (μεταβολὴ κατὰ γένος), in the particular case of phthora nana a change to the enharmonic genus. Today the "nana" intonation has become the standard name of the third authentic mode which is called "echos tritos" (ἦχος τρίτος) in Greek and "third glas" (третий Гласъ) in Old Church Slavonic.

The different functions of phthora nana

In the theory and notation of Byzantine and Orthodox chant nana is the name of a special phthora which had been used in different ways according to its historic context:[1]

- as a phthora which has its proper melos (intonation and cadence formulas), it may denote a special kind of echos (mode) that has been identified with the echos tritos (third mode) since the 16th century, but deviates from the later diatonic echos tritos by the division of its tonal system and its tetrachord. The name "νανὰ" (ʅʅ) was used for its proper enechema, and within the Hagiopolitan Octoechos whole troparia can be found in the tropologion or the chant book Octoechos which are composed in the melos of phthora nana (φθορά νανὰ).

- within the heirmologic or sticheraric melos, it may denote a temporary change to the enharmonic genus (μεταβολὴ κατὰ γένος) and to the triphonic tone system (μεταβολὴ κατὰ σύστημα) within another mode, like echos tritos, echos plagios tetartos or echos plagios protos (plagal first mode) for instance, to an intervallic structure and tone system that is proper to phthora nana as an own echos.[2]

- as echos kratema, phthora nana could used as an own mode which had been used in improvised sections like kratemata or teretismoi which had been sung over abstract syllables. Byzantine composers like Manuel Chrysaphes the Lampadarios mentioned, that the phthora nana always leads to the echos plagios tetartos (fourth plagal mode), before the melos can change into another mode.

- as exoteric "phthora atzem", the sign was used for the transcription of music composed in makam acem, a makam connected to a certain Persian dastgah.

- as a modulation sign, phthora nana played a crucial role to change between the third to the plagal fourth mode. Hence, there can be found some parallels between the b flat as used by Guido of Arezzo, and the temporary use of phthora nana in psaltic compositions which changed between the modes. As such phthora nana was used as an alteration sign within the heptaphonic solfeggio of Chrysanthos' New Method, which transcribed its triphonic tone system by a frequent use transposition (a certain μεταβολὴ κατὰ τόνον which turns γα into νη similar to the Guidonian mutation memorised as «F fa ut»).

Hagiopolites treatise about phthora nana

It is supposed that the Hagiopolites treatise served during the 9th century as a manual preceding a chant book called tropologion. The book contained a collection of simple hymns troparia as well as heirmoi which served as melodic models (μέλοι) for the 10 modes of Octoechos.

Nana holds the status one of the two "special" additional echoi or "mesoi" (medial forms between authentic and plagal echoi) in the system of the Hagiopolitan Octoechos. The other one is called nenano. Already in the Hagiopolites treatise the phthorai nana and nenano have been characterized as both echoi and "not echoi, but phthorai" (→ phthora). This means that they were proper modes with their own models, but they had to be integrated within the Octoechos and its eight-week cycle.[3] Thus, phthora nana was subordinated to the tetartos, and the treatise also referred to it as "Mesos tetartos": as a third medial mode of the tetartos which was neither authentic (kyrios) nor plagal (plagios).

Phthora nana according to the theory and practice of psaltic art

The concrete intervals of the enharmonic genus are less subject than the explanation of relationships between the modes. Often certain paragraphs of the Hagiopolites concerned about the phthora nana have been re-interpreted again and again according to the current tradition of psaltic art.[4]

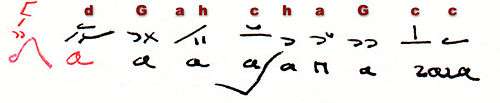

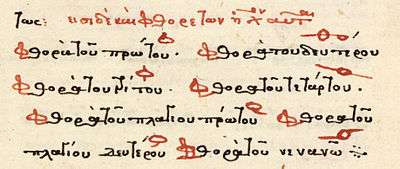

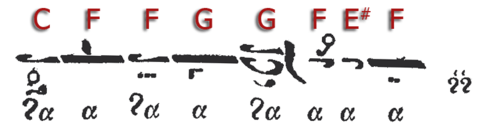

Its enechema

In contemporary theoretical explanations the phthora nana had not only been regarded as a melodic model for stichera and heirmoi, but also as a transition model as well, which mainly connected tritos with tetartos echoi.

According to theoretical explanations of the Papadike, phthora nana was not only defined by its melos like a proper echos itself, as such it had been subordinated to certain echoi already in the Hagiopolites treatise. Manuel Chrysaphes, Lampadarios at the Byzantine court, emphasised that phthora nana is only used as a phthora of the echos tritos, but within its melos it causes always a change into the echos plagios tetartos. Any other changes have to be made after the transition into the plagios tetartos:

εἰ δὲ τρίτου μόνον, ἵνα κατέλθῃς καὶ τὸν πλάγιον τετάρτου ἀνεμποδίστως καὶ ποιήσῃς καὶ τὸν ἦχον, καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα ὡς βούλει εἰς τὰ ἔμποσθεν ποιήσεις.[5]

He also mentioned that the phthora had its own solfège (parallage), so that it solved the diatonic echos tritos and binds it to the echos plagios tetartos (δεσμοῦσι καὶ λύουσι "binding and solving").

αὕτη δὲ ἡ τοῦ νανὰ φθορά, ἥτις ἐστὶν ἀπὸ παραλλαγῶν ἦχος τρίτος, οὑχ οὕτως, ἀλλὰ σχεδὸν εἰπεῖν ἔστιν ὡς ἦχος κύριος, διότι καὶ στιχηρὰ ἰδιόμελα πολλὰ ἔχει καὶ προσόμοια καὶ εἱρμοὺς καὶ καλοφωνικὰ στιχηρά, ὡς οἱ κύριοι ἦχοι. ἀλλὰ καὶ ἀλληλουϊάρια εἰς τὸν πολυέλεον καὶ εἰς τὸν ἄμωμον τῶν λαϊκῶν. καὶ εἰκότως ἂν καλέσειε ταύτην ἦχον καὶ οὐ φθοράν, καθὼς ἔχει καὶ ἡ τοῦ νενανῶ γλυκυτάτη καὶ λεπτοτάτη φθορά.[6]

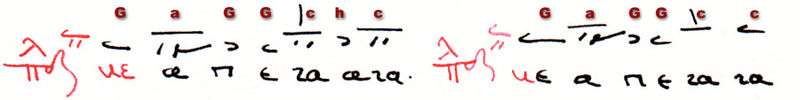

The distinction, that it was by the own solfège (apo parallagon) "like a kyrios echos of its own" (os echos kyrios),[7] meant on the surface, that the tritos could be based on the octave on B flat (heptaphonia) with the finalis F, while it had to change into the tetartos octave which was based on C and therefore used b natural as seventh degree.[8] The triphonic solfège could be solved again from the enharmonic into the diatonic genus, but it was in fact not just a change of the genus (μεταβολὴ κατὰ γένος, metavole kata genos), but also a change from the triphonic into the tetraphonic tone system (μεταβολὴ κατὰ σύστημα, metavole kata systema).[9] It was not organised by separated tetrachords (tetraphonia), but by connected ones (triphonia: C—F—b flat). Hence, the "own triphonic parallage" intermediated between both octave species, which were otherwise very far from each other. Already in this transitional function it formed an alternative melos of the tetartos echoi.

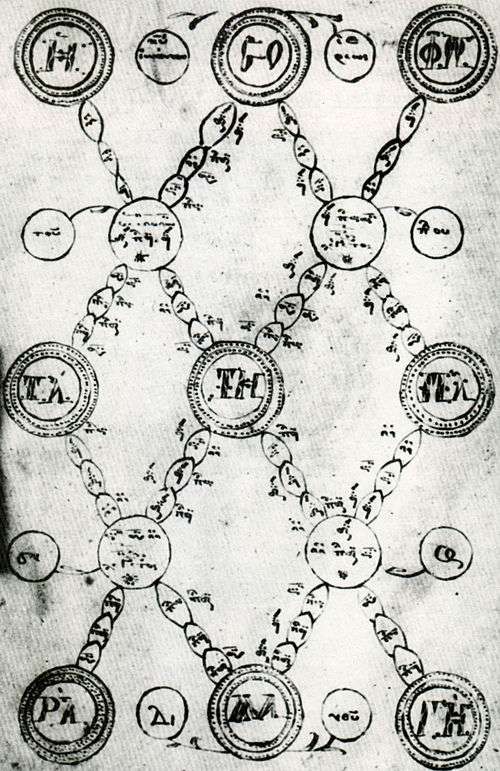

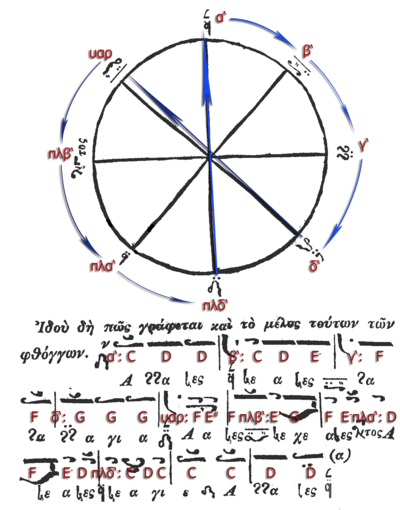

Its tone system

The phthora could intermediate, because it was distinct by its triphonic tone system and its enharmonic genus (the minor tone was always on the top of a tetrachord and smaller than a Western half tone—a diesis). Ioannis Plousiadinos invented an own system of parallage in shape of a square made up by four X. It was constructed to represent the triphonic combinations of conjunct tetrachords, but only the last two X on the bottom described the triphonia of the phthora nana—the triphonia based on echos varys (left) and the triphonia based on the plagios tetartos (right). Both possibilities were illustrated at the end of John Koukouzeles' didactic chant Mega Ison.[10]

Its great sign and its dynamis as echos kratema

The Papadikai list between six and ten phthorai which represent the ten modes of the Hagiopolitan Octoechos—the diatonic eight modes (which did not need eight phthorai, since the echoi just represented the four elements of a tetrachord) and the two additional phthorai as their own echoi.[11]

In this very particular sense, the term "phthora" did neither refer to nenano nor nana, but simply meant the use of a transposition sign in order to indicate the precise place of a temporary transposition (μεταβολὴ κατὰ τόνον).

γνωστών σοι δὲ ἔστω καὶ τοῦτο, ὅτι ἡ φθορὰ αὕτη οὐκ ἔχει καθώς ἐστιν ἡ τοῦ πρώτου ἢ τοῦ δευτέρου, ἢ τοῦ τρίτου, ἢ τοῦ τετάρτου, ἤ τοῦ πλαγίου δευτέρου, διότι αἱ τούτων τῶν ἤχων φθοραὶ δεσμοῦσι καὶ λύουσι ταχίον καὶ ποιοῦσιν ἐναλλαγὴν μερικὴν πὸ ἦχον εἰς ἄλλον καὶ ἔχουσι τοῦτο καὶ μόνον.[12]

Note also, that these phthorai [νενανῶ and νανὰ] are different from those of ἦχος πρῶτος, ἦχος δεύτερος, ἦχος τρίτος, and ἦχος τέταρτος or ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου, since the phthorai of the latter [diatonic] echoi bind or solve quickly and thus, they only create a temporary change from one echos to another one, this is the only purpose they have.

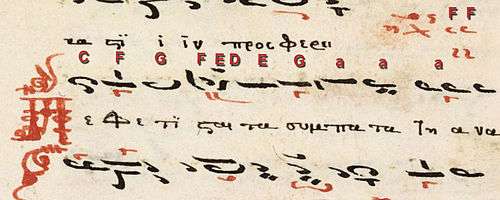

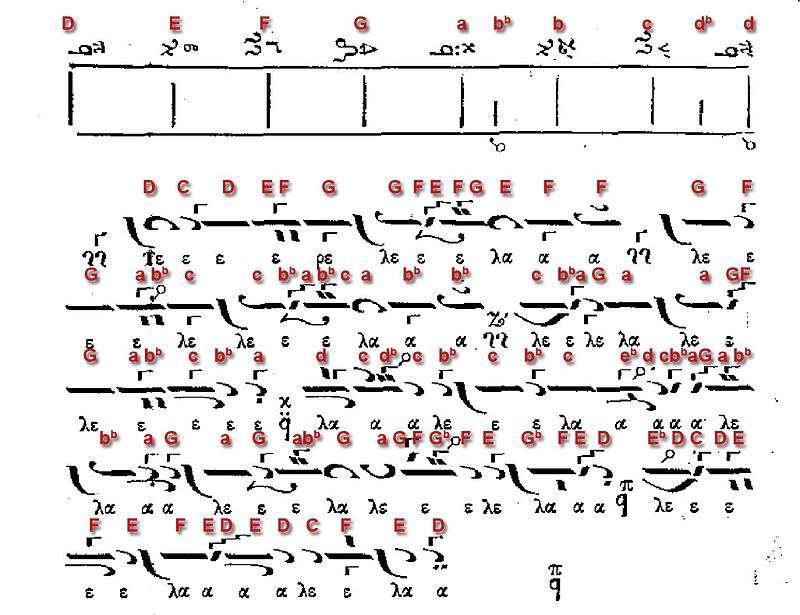

The list of phthora did not include one to indicate a change into the melos of phthora nana. This change was instead caused by one of the great signs (μεγάλα σημαδία), the xeron klasma (ξηρὸν κλάσμα), like here in the sticherarion of the Biblioteca ambrosiana, where the medial signature of phthora nana (a temporary change into its melos) is prepared by this great sign.[13]

This sticheron could be sung as well by a protopsaltes in the soloistic kalophonic style. If the medial signature of nana was the end of the section chosen for the realisation of a sticheron kalophonikon, this sign could cause, that a whole kratema, a section in abstract syllables like το—το—το for instance, was created in the phthora nana as an echos kratema.[14]

Nana as exoteric phthora atzem

The phthora nana was called in various theories "phthora atzem" which referred to perde acem (the fret on the long necked lute tambur called "acem" which was a common reference for Ottoman musicians) or even to makam acem—the "Persian makam" or "phthora." Panagiotes Keltzanides' edition offered a seyir—a melodic example to illustrate makam acem—on page 81:

It is close to the melodic models of the Persian Dastgāh-e Šur.

The enharmonic echoi of the current Octoechos

The reform of the Byzantine neume notation in the early 19th century redefined the mele according to each genre (troparic, heirmologic, sticheraric, papadic), it also transcribed for the first time the rhythm which was so far part of an oral tradition or method, how to do the thesis of the melos. In these transcriptions the diatonic tritos echoi had little relevance. Chrysanthos of Madytos, together with Chourmouzios the Archivist and Gregorios the Protopsaltes one of the three "great teachers" that undertook the reform, published a treatise explaining the principles of the new system, entitled "Theoretikon Mega tes Mousikes".[15]

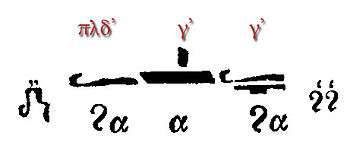

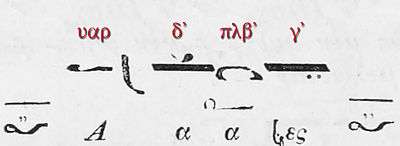

While there was once a diatonic form of echos tritos and echos varys, it has no longer any relevance for the current tradition of Orthodox chant, even if it based on Byzantine monodic chant. Orthodox chanters know nowadays only the intonation "nana" (ʅʅ), when they would like to perform melodies composed in echos tritos. Already Papadikai of the 16th century identified "nana" signature in their lists with the diatonic intonation "aneanes."[16] But its long formula was already replaced by the short of νανὰ in Chrysanthos explanation of the former papadic practice of solfège using the enechemata:

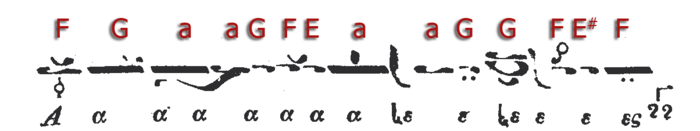

This simple form is used until today, but Chrysanthos also developed its whole melos as a kind of exegesis ("interpretation") of the simple traditional echema of phthora nana:

Chrysanthos' exegesis of the real nana intonation uses the enharmonic intervals:

Διὰ τοῦτο ὅταν τὸ μέλος τοῦ ἐναρμονίου γένους ἄρχηται ἀπὸ τοῦ γα, θέλει νὰ συμφωνῇ μὲ τὸν γα ἡ ζω ὕφεσις, καὶ ὄχι ὁ νη φθόγγος. Καὶ ἐκεῖνο ὅπερ εἰς τὴν διατονικὴν καὶ χρωματικὴν κλίμακα ἐγίνετο διὰ τῆς τετραφωνίας, ἐδῶ γίνεται διὰ τῆς τριφωνίαςὭστε συγκροτοῦνται καὶ ἐδῶ τετράχορδα συνημμένα ὅμοια, διότι ἔχουσι τὰ ἐν μέσῳ διαστήματα ἴσα· τὸ μὲν νη πα ἴσον τῷ γα δι· τὸ δὲ πα [βου δίεσις], ἴσον τῷ δι κε· τὸ δὲ [βου δίεσις] γα, ἴσον τῷ κε [ζω ὕφεσις−6]· καὶ τὰ λοιπά.[17]

- νη πα [βου δίεσις] γα, γα δι κε [ζω ὕφεσις−6], [ζω ὕφεσις−6] νη πα [βου ὕφεσις−6].

Hence, if the melos of the enharmonic genus starts on F γα, F γα and b flat [ζω' ὕφεσις−6] should be symphonous, and not the phthongos c νη'. And like the diatonic and chromatic scales are made of tetraphonia, here they are made of triphonia:

- C νη—D πα—E sharp [βου δίεσις]—F γα, F γα—G δι—a κε—b flat [ζω' ὕφεσις−6], b flat [ζω' ὕφεσις−6]—c νη'—d πα'—e flat [βου' ὕφεσις−6].

Thus, also conjunct similar tetrachords are constructed by the same intervals in the middle [12+13+3=28]: C νη—D πα is equal to F γα—G δι, D πα—E sharp [βου δίεσις] to G δι—a κε, E sharp [βου δίεσις]—F γα is equal to a κε—b flat [ζω' ὕφεσις−6], etc.

He applied this intonation to the traditional varys enechema:

There is also a diatonic form of echos varys,[18] but according to Chrysanthos' adaption to the Ottoman tone system it was no longer based on a pentachord between kyrios tritos and varys, but on a tritonus on a low b natural.[19]

References

- ↑ For a general description of the different aspects of phthora see Ioannis Zannos (1994, 181–187).

- ↑ See André Barbera's article about "Metabole." "Triphonia" (σύστημα κατὰ τριφωνίαν) is the Greek name for a tone system which is organized in conjunct tetrachords, in case of Nana: C πλδ'—D α'—E β'—F γ'/πλδ'—G α'—a β'—b flat γ'. It also corresponds to the ancient Greek "lesser perfect system."

- ↑ See the quotation in the article of phthora nenano which concerned both phthorai.

- ↑ See the quotations collected by Ioannis Zannos (1994, 103–117).

- ↑ Manuel Chrysaphes (Conomos 1985, 58f).

- ↑ Manuel Chrysaphes (Conomos 1985, 58f).

- ↑ Manuel Chrysaphes illustrates the autonomy of phthora nana, that whole heirmoi, idiomela and prosomoia, stichera kalophonika, alleluiaria and polyeleoi had been composed just in this phthora as if it was a real kyrios echos.

- ↑ Likewise it could change from tritos, F—f with the finalis c, to the tetartos octave (G—g with f sharp) and its plagal finalis G.

- ↑ Zum Begriff der "Metabole" siehe Barbera (2011).

- ↑ See Kyriatzides' edition (1896, 141–144) of Chourmouzios' transcription (EBE MΠΤ 703).

- ↑ A published collection of Byzantine music treatises is found in Lorenzo Tardo's «L'antica melurgia bizantina» (1938).

- ↑ Manuel Chrysaphes (Conomos 1985, 58).

- ↑ For a general study see the dissertation by Maria Alexandru (2000).

- ↑ See for example the sticheron kalophonikon over the first section of the sticheron idiomelon Τῷ τριττῷ τῆς ἐρωτήσεως in echos tetartos dedicated to Saint Peter (29 June ). John Koukouzeles' kratima was composed in phthora nana as "echos kratema."

- ↑ Chrysanthos (1832).

- ↑ See GB-Lbl Harley 5544, fol. 7r-v.

- ↑ Chrysanthos (1832, p. 114, § 261).

- ↑ According to Georgios Konstantinou (1997), the theory of the school of Lycourgos Angelopoulos and Simon Karas, also the phthora nana is sung in a so-called "hard diatonic" intonation which sounds like the modern equal temperament in comparison with traditional singers, who still intone the melos of the phthora with enharmonic intervals.

- ↑ Oliver Gerlach (2015). Panagiotes Keltzanides (1881, 131–144) relates the makamlar dügah, evic, acem kürdi, sultanin arak, beste-nigar, beste-isfahan, nihavend and ferahnak, and evic buselik with the mele of echos varys based on fret "arak."

Theoretical sources

Hagiopolites

- Raasted, Jørgen, ed. (1983), The Hagiopolites: A Byzantine Treatise on Musical Theory, Cahiers de l'Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin, 45, Copenhagen: Paludan.

- Bellermann, Johann Friedrich; Najock, Dietmar, eds. (1972), Drei anonyme griechische Traktate über die Musik, Göttingen: Hubert.

Dialogue treatises

- Hannick, Christian; Wolfram, Gerda, eds. (1997), Die Erotapokriseis des Pseudo-Johannes Damaskenos zum Kirchengesang, Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica, 5, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 3-7001-2520-8.

Papadikai and their explanations

- Alexandru, Maria (1996). "Koukouzeles' Mega Ison: Ansätze einer kritischen Edition". Cahiers de l'Institut du Moyen-Âge grec et latin. 66: 3–23.

- Conomos, Dimitri, ed. (1985), The Treatise of Manuel Chrysaphes, the Lampadarios: [Περὶ τῶν ἐνθεωρουμένων τῇ ψαλτικῇ τέχνῃ καὶ ὧν φρουνοῦσι κακῶς τινες περὶ αὐτῶν] On the Theory of the Art of Chanting and on Certain Erroneous Views that some hold about it (Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery MS 1120, July 1458), Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica, 2, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 978-3-7001-0732-3.

- Fleischer, Oskar, ed. (1904), "Die Papadike von Messina", Die spätgriechische Tonschrift, Neumen-Studien, 3, Berlin: Georg Reimer, pp. 15–50; fig. B3-B24 [Papadike of the Codex Chrysander], retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Hannick, Christian; Wolfram, Gerda, eds. (1985), Gabriel Hieromonachus: [Περὶ τῶν ἐν τῇ ψαλτικῇ σημαδίων καὶ τῆς τούτων ἐτυμολογίας] Abhandlung über den Kirchengesang, Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica, 1, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 3-7001-0729-3.

- Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes. "London, British Library, Harley Ms. 5544, fol. 3r-8v". Papadike and the Anastasimatarion of Chrysaphes the New, and an incomplete Anthology for the Divine Liturgies (17th century). British Library. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Chourmouzios Chartophylakos (1896). Kyriazides, Agathangelos, ed. "Τὸ Μέγα Ἴσον τῆς Παπαδικῆς μελισθὲν παρὰ Ἰωάννου Μαΐστορος τοῦ Κουκκουζέλη". Ἐν Ἄνθος τῆς καθ' ἡμᾶς Ἐκκλησιαστικῆς Μουσικῆς περιέχον τὴν Ἀκολουθίαν τοῦ Ἐσπερίνου, τοῦ Ὅρθρου καὶ τῆς Λειτουργίας μετὰ καλλοφωνικῶν Εἴρμων μελοποιηθὲν παρὰ διάφορων ἀρχαιῶν καὶ νεωτερῶν Μουσικόδιδασκαλων. Istanbul: Alexandros Nomismatides: 127–144.

- Tardo, Lorenzo (1938), "Papadiche", L'antica melurgia bizantina, Grottaferrata: Scuola Tipografica Italo Orientale "S. Nilo", pp. 151–163.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chrysanthos of Madytos. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Enechemata. |

Treatises of the New Method (since 19th century)

- Chrysanthos of Madytos (1832), Θεωρητικὸν μεγὰ τῆς Μουσικῆς, Triest: Michele Weis, retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Anastasiou, Spiridon; Keïvelis, Ioannis G. (1856). Απάνθισμα ή Μεδζμουαϊ μακαμάτ περιέχον μεν διάφορα τουρκικά άσματα. Istanbul: Taddaios Tividesian. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Keltzanides, Panagiotes (1881). Μεθοδική διδασκαλία θεωρητική τὲ καὶ πρακτική πρὸς ἐκμάθησιν καὶ διάδοσιν τοῦ γνησίου ἐξωτερικοῦ μέλους τῆς καθ᾿ ἡμᾶς Ἑλληνικῆς Μουσικῆς κατ᾿ ἀντιπαράθεσιν πρὸς τὴν Ἀραβοπερσικήν. Istanbul: A. Koromela & Sons.

- Konstantinou, Georgios N. (1997). Θεωρία καί Πράξη τῆς Ἐκκλησιαστικῆς Μουσικῆς. Athens: Nektarios D. Panagopoulos.

Studies

- Alexandru, Maria (2000). Studie über die 'großen Zeichen' der byzantinischen musikalischen Notation unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Periode vom Ende des 12. bis Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts. Universität Kopenhagen.

- Barbera, André. "Metabolē". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Gerlach, Oliver (2014). "'The Heavy Mode (ēchos varys) on the Fret Arak' — Eastern Chant in Istanbul and the Various Influences during the Ottoman Empire". Porphyra. 22: 82–95.

- Zannos, Ioannis (1994). Ichos und Makam - Vergleichende Untersuchungen zum Tonsystem der griechisch-orthodoxen Kirchenmusik und der türkischen Kunstmusik. Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik. Bonn: Verlag für systematische Musikwissenschaft. ISBN 978-3-922626-74-9.

External links

- Phokaeos, Theodoros. "Modern parallage of the cherouvikon composed in phthora nana (echos tritos)". Marios Demetriou.

- Phokaeos, Theodoros. "Cherouvikon composed in phthora nana (echos tritos)". Marios Demetriou.

- Poyraz, Nuri Halil. "Saz semaisi in makam acem".