Balkline and straight rail

Balkline (sometimes spelled balk line[1] or balk-line) is the overarching title of a large array of carom billiards games generally played with two cue balls and a third, red object ball, on a cloth-covered, 5 foot × 10 foot, pocketless table that is divided by balklines on the cloth into marked regions called balk spaces. Such balk spaces define areas of the table surface in which a player may only score up to a threshold number of points while the object balls are within that region.[2][3]

The balkline games developed to make the precursor game, straight rail, more difficult to play and less tedious for spectators to view in light of extraordinary skill developments which allowed top players to score a seemingly endless series of points with the balls barely moving in a confined area of the table playing area.[2][4] Straight rail, unlike the balkline games, had no balk space restrictions, although one was later added. The object of the game is simple: one point, called a "count", is scored each time a player's cue ball makes contact with both object balls (the second cue ball and the third ball) on a single stroke. A win is achieved by reaching an agreed upon number of counts.[2][5]

Carom billiards players of the modern era may find it surprising that balkline ever became necessary given the considerable difficulty of straight rail. Nevertheless, according to Mike Shamos, curator of the U.S. Billiard Archive, "the skill of dedicated players [of straight rail] was so great that they could essentially score at will." The story of straight rail and of the balkline games are thoroughly intertwined and encompass a long and rich history,[2][6] characterized by an astounding series of back and forth developments, akin to a billiards evolutionary arms race, where new rules would be implemented to make the game more difficult and to decrease high runs to keep spectators interested, countered by new shot inventions and skills interdicting each new rule.

Rise and "fall" of straight rail

Straight rail from which the balkline games derive, sometimes called carom billiards, straight billiards, the three-ball game, the carambole game, and the free game (or libre) in Europe, is thought to date to the 18th century, although no exact time of origin is known. It was known as French caroms, French billiards, or the French game in early times, taking those bygone names from the French who popularized it. The derivation of the name straight rail is not clear. An early mention appears in the March 23, 1881 edition of The New York Times[2] wherein it is referred to as "the straight rail game."[7]

At straight rail's inception there was no restriction on the manner of scoring, such as a number of cushions that must be contacted on a shot, as in the game of three cushion billiards, nor a requirement that the balls leave a region of the table, as in the balkline games.[2]

In 1855, the first public stakes straight rail match in the U.S. took place in San Francisco. The contestants, Michael Phelan and a Monsieur Damon of Paris battled for seven hours, but the high run, set by Phelan, was just nine points. A technique soon developed, known as crotching, which vastly increased counts. The "crotch" refers to the space near the corner of a table where the rails meet. By moving the two object balls into the crotch, a player could endlessly score off of them, all the while keeping them immobilized in that corner.[2]

Crotching was quickly banned in 1862. Under the prohibitive rule (the first use of a balk space), the crotch was defined as the triangular region found by connecting a line between the points measuring 4½ inches down each rail forming the corner, and in which only three counts could be scored before at least one ball had to be driven away.[2] The no crotching rule is still in place in the official rules for straight rail promulgated by the Billiard Congress of America, the governing body of billiards in the United States.[8]

Straight rail became progressively more popular and skill in the game increased commensurately.[2] For example, Albert Garnier, author of Scientific Billiards (1880)[9] and the champion of the first world title straight rail tournament in 1873, averaged 12 points over the course of the competition and posted a high run of 113. Although unimpressive compared with later records (in 1931 legendary player Charlie Peterson achieved an astounding 10,232 high run count), the many-fold increase in scoring average and high run as compared with the 1855 contest was a result of refinement of gather shots and, most importantly, the development of a variety of "nurse" techniques[2] (also called nursery cannons in the UK).[10]

A gather shot is one in which the intent is to bring the cue ball and object balls together, ideally near a rail. A nurse describes fine, close-quarters manipulation of object balls once gathered near a rail, which results in both balls being touched by the cue ball, but with all three balls barely moving, or that result in a position that can be duplicated over and over.[2]

There are many types of nurses, including the chuck nurse, pass nurse, Dion's nurse, edge nurse, rail nurse, and others. The most important of these is the rail nurse—so important to the game, in fact, that sometimes the nurse is simply called the "straight rail"—which involves the progressive nudging of the object balls down a rail, ideally moving them just a few centimeters on each count, keeping them close together and positioned at the end of each stroke in the same or near the same configuration such that the nurse can be replicated again and again. There is great skill and technique involved in maintaining a nurse, as well as in fixing a nurse or gathering again when a nurse breaks down too far for recovery.[2][11]

At the U.S. straight rail professional tournament held in 1879, Jacob Schaefer, Sr. scored 690 points in a single inning at the table (with the prohibition against crotching in place). With the balls barely moving and repetitively hit, there was little for the fans to watch.[12] Schaefer was quickly "hailed as 'the wizard'... Billiards officials, recognizing that Schaefer was a peerless performer in "nursing," wrote an 8 inch balkline into the rules..."[13]

This marked the demise of professional straight rail in the U.S., which only had a six year run from 1873 to 1879. Meanwhile, straight rail professional play continued in Europe, with high run counts consistently climbing. Frenchman Maurice Vignaux posted a 1,531 count in Paris in 1880, while American George Spears had a high run of 5,041 in 1890. Later runs of over 10,000, in addition to the one previously noted, have been accurately reported.[2]

Today, straight rail play is relatively uncommon in the U.S. but retains popularity in Europe, where it is considered a fine practice game for both balkline and three cushion billiards. Additionally, Europe hosts professional competitions known as pentathlons after the ancient Greek Olympic competitions, in which straight rail is featured as one of five billiards disciplines at which players compete, the other four being 47.1 balkline, cushion caroms, 71.2 balkline and three-cushion billiards[2]

Ascendancy of balkline

The new game appearing in 1879, called the champion's game or limited-rail, is considered an intermediary game between straight rail and balkline and was designed with the specific intent of frustrating the rail nurse.[2] The game employed diagonal lines – balklines – at the table's corners to regions where counts were restricted, thus "cutting off four triangular spaces in the four corners, [taking] away 28 inches of the 'nursing' surface of the end rails and 56 inches on the long rails."[14]

Reporting on the first tournament at which the champion's game was featured in 1879, sponsored by H. W. Collender, The New York Times wrote: "taken as a test, the games thus far played indicate that the new game has taken well with the public, for whose amusement it was chiefly designed. That the rules binding it have effected a great improvement on the ordinary game of French caroms there can be no doubt."[15][16]

Despite its divergence from straight rail, the champion's game simply expanded the dimensions of the balk space defined under the existing crotch prohibition. The aim of stopping the rail nurse was not successful. Jacob Schaefer, Sr. the same player whose 690 count was in large part responsible for the institution of new rules, in short order developed a technique allowing him and other players to reverse the direction of the rail nurse. The balls could thus be endlessly nursed down the rail, reversed in orientation, and nursed the opposite direction without ever even entering the expanded balk space.[2]

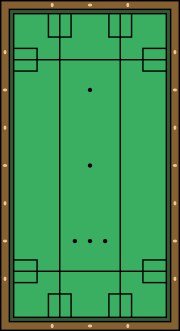

In the balkline games, rather than drawing balklines a few inches from the corners, the entire table is divided into rectangular balk spaces, by drawing balklines a certain distance lengthwise and widthwise across the length of the table a set distance parallel out from each rail. This divides the table into eight rectangular balk spaces.[2]

For the most part, the differences between one balkline game to another is defined by two measures: 1) the spacing of the balklines, and 2) the number of points that are allowed in each balk space before at least one ball must leave the region. Generally, balkline games, and their particular restrictions, are given numerical names indicating both of these characteristics; the first number indicated either inches or centimeters depending on the game, and the second, after a dot, indicates the count restriction in balk spaces, which is always either one or two. For example, in 18.2 balkline, one of the more prominent balkline games and of U.S. origin, the name indicates that balklines are drawn 18 inches distant from each rail, and only two counts are allowed in a balk space before a ball must leave.[2][17] By contrast, in 71.2 balkline, of French invention, lines are drawn 71 centimeters distant from each rail, also with a two count restriction for balk spaces.[18]

The first true balkline game was proposed in 1875 but was rejected. However, because high runs once again increased as skill compensated for the new conditions, in 1883 the balkline games were accepted, replacing the Champion's game in tournament play. Although initially the balklines were set closer to the rails, first at 8, then 10 and for a time at 12 inches, a contingent of the great players of the era, Joseph Dion, William Sexton, Maurice Daly, George F. Slosson and Jacob Schaefer, Sr. agreed upon 14 inches as the better measure. In 1885, 14 inches was adopted as the official balkline distance. Later a variety of distances and count restrictions were proposed and tried.[19]

Balklines did not stop the rail nurse but they did restrict its use. Soon a new type of nurse was developed which exploited a loophole in balkline rules: so long as both object balls straddled a balkline, there was no restriction on counts, as each ball lay in a separate balk space. The new technique, deemed the anchor nurse, again increased runs greatly. The anchor nurse is a stationary shot in which both object balls, falling on either side of a balkline, are hit repeatedly without moving—they are "anchored" in place. Once again a new rule was necessary to combat this new skill development; thus arose the Parker's box in 1894.[2]

Named after Chicagoan J. E. Parker, the tournament director who suggested it after Jacob Schaefer, Sr. and Frank C. Ives both posted extensive runs at his room using the anchor nurse, the Parker's box is a rectangular marking straddling the spot where the balkline meets each rail. Enclosing a space 3½ inches out from the rail and 7 inches across, the box marks a region where both balls are considered in balk, despite that the object balls may technically fall on either side of a balkline. When first instituted, ten shots were allowed while the balls were inside the Parker's box or "in anchor". This was reduced to five in 1896 when 18.2 balkline was gaining popularity.[2]

True to form, the next skill development response was the chuck nurse, known as a rocking cannon in the United Kingdom. With one ball frozen to the cushion in the Parker's box, but the second object ball away from the rail just outside the borders of the Parker's box, the cue ball is gently rebounded off the frozen ball not moving it, but with just enough speed to meet the other object ball which rocks in place, but does not change position. In 1912, playing 18.2 balkline, William A. Spinks ran 1,010 continuous points using the chuck nurse and broke off his run without ever missing.[2]

There were a number of proposals to curtail the chuck nurse's effectiveness, including removing the four balk spaces on the end rails where dominant players in the 1920s such as Willie Hoppe, Welker Cochran and Jake Schaefer, Jr, (Jacob Sr.'s son) had perfected their nursing skills, but leaving balk spaces in place on the long rails.[20]

The solution ultimately reached, and the change that brought the general rules of balkline into configuration with what is played today, was the establishment of eight anchor spaces. The anchor space is simply a doubling of the Parker's box to 7 inches distant from the rail and 14 inches parallel to the rail; simple, but placing the chuck nurse out of reach. The new restriction was instituted for a 1914 tournament, the first in 14.1 balkline, specifically to curtail the chuck nurse.[2]

Over its history balkline has had many variations including 8.2, 10.2, 12.2, 12½.2, 13.2, 14.1, 14.2, 18.1, 18.2, 28.2, 38.2, 39.2, 42.2, 45.1, 45.2, 47.1, 47.2, 57.2 and 71.2 balkline. In its various incarnations, balkline was the predominant billiards discipline from 1883 to the 1930s when it was overtaken by three cushion billiards and pocket billiards. Balkline is not very common in the U.S. but still enjoys a large popularity in Europe and the Far East.[2][21]

References

- ↑ "To Play 14-inch Balk Line". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. November 24, 1896. p. 10. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Shamos, Michael Ian (1993). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York, NY: Lyons & Burford. pp. 8, 15, 41, 46, 50–1, 86–7, 104, 108, 157–8, 167, 232–4. ISBN 1-55821-219-1.

- ↑ Cohen, Neil, ed. (1994). The Everything You Want to Know About Sport Encyclopedia. Toronto: Bantam Books. p. 79. ISBN 0-553-48166-5.

- ↑ Stein, Victor; Paul Rubino (1994). The Billiard Encyclopedia: An Illustrated History of the Sport (2nd ed.). New York: Blue Book Publications. pp. 301–2. ISBN 1-886768-06-4.

- ↑ Grolier Inc., ed. (1998). The Encyclopedia Americana. Danbury, Ct: Grolier Incorporated. p. 746. ISBN 0-7172-0131-7.

- ↑ Hoyle, Edmond (1907). Hoyle's Games (Autograph ed.). New York: A. L. Burt Company. p. 40.

- ↑ The New York Times (March 23, 1881). Carter Beats Gallagher.; the Toledo Player Gains the Lead Early and Retains it till the End. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ↑ BCA Rules Committee (1998). Billiards — The Billiard Congress of America Official Rules and Records Book (50th anniversary commemorative ed.). Coralville, Iowa: Billiard Congress of America. pp. 85–6. ISBN 1-87849-308-6.

- ↑ Garnier, Albert Scientific Billiards. Retrieved February 2014.

- ↑ Hoppe, Willie (1975). Thomas Emmett Crozier, ed. Thirty Years of Billiards. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23126-7.

- ↑ Jim Loy (1998). The Rail Nurse Archived January 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ Shamos, Michael Ian (1991). Pool. Hotho & Co., June, 1991. ISBN 99938-704-3-9.

- ↑ Menke, Frank Grant (1939). Encyclopedia of Sports. New York City: F. G. Menke, Inc. p. 80.

- ↑ New York Times Company (November 10, 1879). "Billiards under New Rules.; a Tournament in Which Rail Play Will Be Restricted-the Programme". The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ↑ New York Times Company (November 17, 1879). Miscellaneous City News; First Week of the New Game. Record of the Players in the Collender "Champion's Game" Tournament. The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ↑ "Meeting of the Champions; The Big Billiard Tournament to Begin To-morrow — What Ives, Schaefer, and Slosson Have Been Doing in Practice — The Older Players Not Afraid of the Big Runs Made by Ives — Something About the Rise and Progress of the Young 'Napoleon' of the Billiard World", no byline, The New York Times, December 10, 1893, p. 10; The New York Times Company, New York, NY, USA. Uses the term "champion's game".

- ↑ "Change Is Planned in Balkline Game; Miller Proposal Would Eliminate Four of Nine Zones in Effort to Stop Long Runs". The New York Times. August 10, 1924. p. 24. Retrieved May 4, 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Kieran, John (December 7, 1937). "Sports of the Times; Reg. U. S. Pat. Off". The New York Times. p. 35. Retrieved May 4, 2010. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ New York Times Company (October 28, 1888). Drawbacks to Billiards; Personal Solicitude the Source of Nearly All. Lost Professional Pride and Pluck Both Evades Public Matches and Suppresses Them. The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ↑ New York Times Company (August 10, 1924). Change Is Planned in Balkline Game; Miller Proposal Would Eliminate Four of Nine Zones in Effort to Stop Long Runs. The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- ↑ New York Times Company (October 24, 1919). Hoppe Hoppe Adds Morningstar's Scalp to His Collection Made in Billiard Title Tourney; Hoppe Maintains Row of Victories Billiard Champion Takes Measure of Morningstar in 18.2 True Play at Astor. Cochran Makes Long Run Sets High Mark for Tourney of 165 in Beating Yamada--Sutton's Play Falls Off-Badly. Hoppe Gets Long Lead. Gathers Big Cluster. High Run of 165. Mostly Cushion Shots. Sutton Not in Form. Schaefer Has Little Trouble. The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

External links

- Animation showing the "rail nurse" with a description.

- Animation showing the "chuck nurse" with a description.