2014 Nuclear Security Summit

| 2014 Nuclear Security Summit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Host country |

|

| Date | March 24–25, 2014 |

| Venue(s) | World Forum Convention Center |

| Cities | The Hague |

| Participants | 58 representatives |

| Follows | 2012 Nuclear Security Summit |

| Precedes | 2016 Nuclear Security Summit |

| Website |

nss2014 |

The 2014 Nuclear Security Summit was a summit held in The Hague, the Netherlands, on March 24 and 25, 2014.[1] It was the third edition of the conference, succeeding the 2012 Nuclear Security Summit. The 2014 summit was attended by 58 world leaders (5 of which from observing international organizations), some 5,000 delegates and some 3,000 journalists.[2] The representatives attending the summit included U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The main goal of the conference was generally to improve international cooperation and more specifically to assess which of the objectives that were set at the previous summits in Washington, D.C. and Seoul had not been accomplished in the previous four years and proposing ways of achieving them.[3]

The Nuclear Security Summit aimed to prevent nuclear terrorism by:[1]

- reducing the amount of dangerous nuclear material in the world - especially Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU);

- improving the security of all nuclear material and radioactive sources;

- improving international cooperation.

Some of the participating countries were interested in leading a certain security theme to a higher level. They could do so by offering a 'gift basket',[3] which is an extra initiative that can function as a role model for a specific security aspect (provided that it is supported by other countries). The Netherlands, for example, has been developing a gift basket that improves expertise and (international) cooperation regarding nuclear forensics with the help of the Netherlands Forensic Institute.

Although nuclear terrorism and its prevention by reducing and securing nuclear supplies are officially the main topic, the Ukraine crisis overshadowed the talks. The event formed the backdrop for an emergency meeting of G7 leaders on Russia’s annexation of Crimea earlier in March 2014.[4][5] Russian President Vladimir Putin was not attending, instead sending Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, who was expected to hold talks with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. Notable absentees from the summit were North Korea and Iran, excluded by mutual consent.

Background

Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) and plutonium can be used to manufacture nuclear weapons. However, HEU is also used in research reactors and for medical isotope production. Plutonium is used by some countries as fuel for nuclear power plants. The leaders gathered at the Neclear Security Summit aimed to minimise the use of these materials, the amount kept in storage and the number of storage locations, keeping in mind the uses allegedly beneficial to mankind.

In the 4 years since the Washington Nuclear Security Summit in March 2010, NSS countries have taken steps to accomplish this goal, as outlined in their National Progress Reports.

Nuclear and other radioactive materials are used extensively in hospitals, industry and universities. Some of these places with radioactive materials are open to the public. Better securing these materials is one of the main objectives of the Nuclear Security Summits. In addition to better physical security, improving of sensitive information would also help to reduce the likelihood of a terrorist act with radiological or nuclear material, a Dirty bomb.

Installing radiation detection equipment would increase the probability of getting caught when smuggling and this would decrease the likelihood of people trying to acquire the materials in the first place. In these areas the NSS participants reported progress.

Participants

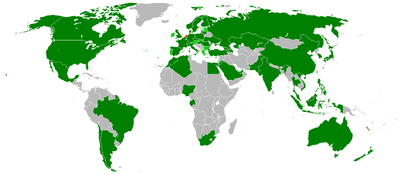

The 2014 Nuclear Security Summit was the largest conference ever held in the Netherlands at the time. The 53 participating countries and 4 observing organizations of the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit were:[6][7]

Reported results

According to the submitted National Progress Reports of the participating states, 26 of the 28 NSS countries that had at least 1 kg of HEU at the time of the Washington Summit indicated that they have taken action to reduce the amount of dangerous nuclear material. Since the Seoul Summit, at least 15 metric tons of HEU had been down-blended to Low Enriched Uranium (LEU), which will be used as fuel for nuclear power plants. This would be the equivalent to approximately 500 nuclear weapons.

Since 2009, 12 countries worldwide (Austria, Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Libya, Mexico, Romania, Serbia, Taiwan, Turkey, Ukraine and Vietnam) had removed all HEU from their territory. 15 NSS countries reported that they had repatriated HEU or plutonium or were in the process of doing so. Some NSS countries were also assisting other countries in efforts to repatriate HEU or plutionium.

During the Summit, 13 countries had subscribed to the HEU-free Joint Statement. They underlined the importance of HEU minimisation and called upon all countries in a position to do so to eliminate all HEU from their territories in advance of the NSS 2016.

17 Countries had converted or were in the process of converting at least 32 of their own research reactors of medical isotope production facilities. NSS countries also assist other countries in converting their reactors. 9 NSS countries reported that they were researching and developing techniques that use LEU instead of HEU.

Almost all NSS countries stated that they had updated or were currently reviewing, updating or revising nuclear security-related legislation, such as that relating to physical protection, transportation and handling of radioactive sources, in order to comply with international guidelines and best practices.

During the summit, 30 countries supported development of a National Legislation Implementation Kit on Nuclear Security that countries could use as building blocks to incorporate the various guidelines into binding national regulations

Schedule and Agenda

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

March 24

The schedule for the first day of the summit was as follows:[8]

- From 1:30 pm (CET) prime minister Mark Rutte receives the heads of delegation at the World Forum Convention Center in The Hague.

- The session is opened at 3:00 pm (CET).

- The conference continues at 3:30 pm (CET) behind closed doors. Press briefings and bilateral meetings are also held.

- King Willem-Alexander receives the heads of delegation at Huis ten Bosch for a joint dinner from 7:00 pm (CET).

Additionally, an emergency meeting of the G7 took place at 6:30 pm (CET) at the Catshuis (the official residence of the prime minister) to discuss the situation in Crimea.[9] Prior to the meeting, British prime minister David Cameron announced that the upcoming G8 meeting in June that was planned to be held in Russia will not occur in that country due to its role in the Crimean crisis.[10]

March 25

The summit continued the next day with the following events:[8]

- The days starts with informal discussion on the future of the NSS process at 10:00 am (CET).

- From 10:10 am (CET) press briefings and bilateral meetings will be held.

- The official group photo with the heads of delegation is taken at 12:15 pm (CET).[11]

- At 3:15 pm (CET) the session will be closed.

- Final press conferences will follow starting at 4:00 pm (CET).

Agenda

The Hague Summit built upon the accomplishments of the two previous Nuclear Security Summits in 2010 and 2012 and focused on three main goals:

- Reducing the amount of dangerous nuclear material in the world.

- Improving the security of all nuclear material and radioactive sources.

- Improving international cooperation.

Summit consequences

Japanese turnover of nuclear material

Japan welcomed the opening of the summit with the pledge that it agreed to transfer to the U.S. a (relatively small) part of its nuclear material: more than 700 pounds of weapons-grade plutonium and a large quantity of highly enriched uranium, a decades-old research stockpile allegedly of American and British origin, said to be large enough "to build dozens of nuclear weapons", according to American and Japanese officials. The amount of highly enriched uranium had not been announced, but was estimated in the press at 450 pounds.

This announcement was considered the biggest single success in the five-year-long push of U.S. President Obama to secure the most dangerous materials. Since he began the meetings with world leaders, 13 nations had eliminated their caches of nuclear materials and many more improved the security measures around their storage facilities, in order to prevent theft by potential terrorists.

For years, Japan's stockpiles of weapons-grade material were not a secret, but its security was criticized, and Iran had cited Japan's stockpiles of bomb-ready material as "evidence of a double standard" about which nations could be trusted. In February 2014, China began denouncing Japan's supply, in apparent warning that a nationalistic turn in Japanese politics could result in the country seeking its own weapons.

At various moments right-wing politicians in Japan had referred to the stockpile as a deterrent, suggesting that it was useful to have material so that the world knows the country could easily fashion it into weapons.[12]

Agreements

In The Hague Nuclear Security Summit Communiqé,the attending leaders raised the bar by committing to minimise their stockpiles of plutonium, in addition to minimising HEU.

Leaders of 35 countries have agreed to adopt the Nuclear Security Guidelines, including Algeria, Armenia, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Mexico, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.[13] The leaders of the remaining 18 countries have refused to adopt the Nuclear Security Guidelines, namely China, Russia, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, Argentina, Thailand, South Africa, Malaysia, Nigeria, Singapore, Egypt, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Jordan, and Gabon.

2016 Summit

The next Nuclear Security Summit will be in 2016, hosted by the United States. During the summit in The Hague, both Washington and Chicago were mentioned as locations.

Security

With the gathering of 58 high officials, security was an absolute priority.[14] As a result, the security measures taken during the summit were unprecedented for the Netherlands.[15] Around 13,000 police officers (four times the amount as during the royal succession in 2013),[16] 4,000 gendarmes, and 4,000 military personnel were deployed.[17] Several NASAMS air-defence systems were placed at various spots around The Hague and two F-16 fighter jets were permanently patrolling The Hague airspace.[18] More F-16s were on stand-by for interception tasks and came into action on March 24 when a cargo plane unintentionally entered Dutch airspace without permission.[19] Apache helicopters were on stand-by as well, and Cougar and Chinook helicopters were available for transportation needs. Police helicopters were also patrolling the airspace. Naval ships were guarding the coastline and NATO assisted the Dutch military with AWACS airplanes.

The area directly around the World Forum Convention Center, where the summit was held, was completely closed off with fences borrowed from the UK which were previously used at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.[20] Because of the heavy security precautions, a number of roads around the World Forum Convention Center and some major motorways between Schiphol Airport and The Hague were partially or completely closed for regular traffic.[21] It was feared that these measures would lead to severe traffic jams in the busy Randstad, but the amount of traffic was less than was expected on the first day of the summit and major problems did not occur, presumably due to the government's advice for commuters to avoid the western Randstad or to take the train instead.[22]

See also

- Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear proliferation

- Proliferation Security Initiative

References

- 1 2 "Nuclear Security Summit 2014". NSS 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Nucleaire top in Den Haag: maatregelen en cijfers". Elsevier (in Dutch). January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- 1 2 "About the NSS". NSS 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ↑ "World leaders gather for Hague nuclear summit". The Washington Post. March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine Crisis Threatens to Overshadow World Nuclear Summit". The Voice of America. March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Countries & Achievements". NSS 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ "NSS 2014: Heads of Delegations" (PDF). NSS 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- 1 2 "Updated Media Note" (PDF). NSS 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Rutte opent NSS-top 2014". NOS (in Dutch). March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "G8 summit 'won't be held in Russia'". BBC. March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Video: leaders getting ready for official group photo". March 24, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Japan to Let U.S. Assume Control of Nuclear Cache". NYT. March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Two thirds NSS countries: from guidelines to law". NOS. March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Het land op zijn kop voor nucleaire top". Telegraaf (in Dutch). November 25, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "'Grootste veiligheidsactie ooit': dit staat Nederland in maart te wachten". Volkskrant (in Dutch). January 27, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "De NSS komt eraan". NOS (in Dutch). March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "NSS is grootste klus voor Defensie". NOS (in Dutch). March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "F-16's in de lucht tijdens top". NOS (in Dutch). March 9, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "F-16's onderscheppen vliegtuig". NOS (in Dutch). March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Londense hekken naar Den Haag". NOS (in Dutch). March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Top ontregelt verkeer Nederland". NOS (in Dutch). March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Verkeersinfarct rond NSS blijft uit". NOS (in Dutch). March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2014 Nuclear Security Summit. |