Addiewell

| Addiewell | |

| Scottish Gaelic: Tobar Adaidh | |

| Scots: Aidieswall | |

Entrance to the Addiewell and Loganlea Memorial Garden |

|

Addiewell |

|

| OS grid reference | NS989625 |

|---|---|

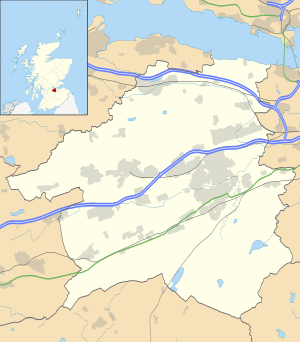

| Civil parish | West Calder |

| Council area | West Lothian |

| Lieutenancy area | West Lothian |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WEST CALDER |

| Postcode district | EH55 |

| Dialling code | 01506 |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | Livingston |

| Scottish Parliament | Almond Valley |

Coordinates: 55°50′42″N 3°36′50″W / 55.845°N 3.614°W

Addiewell (Scots: Aidieswall,[1] Scottish Gaelic: Tobar Adaidh)[2] is a former mining village in the Scottish council area of West Lothian. A new prison, HMP Addiewell, opened in 2008.

History

There are two separate districts, Addiebrownhill and Loganlea. Addiewell is near Stoneyburn and West Calder. There is one church, namely St Thomas the Apostle Church[3] (of the Roman Catholic Church). The former church of Scotland is now used as a warehouse by the owner of one of the village shops.

In 1852 James Young left Manchester to return to live in Scotland. On return he bought the United States-registered patent for the production of paraffin oil by distillation of coal,[4] known as the oil shale industry. Both the US and UK patents were subsequently upheld in both countries in a series of lawsuits, and other producers were obliged to pay him royalties. After his patents expired in 1864,[5] in 1865 Young bought out his business partners at the Bathgate-based chemical works, and choose to build a larger factory at Addiewell, due to its location on the Breich river.[4]

After agreeing purchase of 70 acres (28 ha) 1 mile (1.6 km) west from the village of West Calder,[5] Young needed to develop a model village for his workers. Finding clay beneath the soil, he built a brickworks, allowing him to greatly reduce construction costs. Laid out on the principles set out by Cadbury at Bournville, and developed mainly between 1865 and 1870, a public school was built with accommodation for 327 children.[6] Young named a number of the streets after his heroes, namely: Humphry Davy; Michael Faraday; David Livingstone; Robert Stephenson; and James Watt.[7] However, he operated the village on the principles the developers of the South Wales Coalfield, where by workers were paid in a local currency to ensure that their wages were spent within the village, and that the men did not over drink alcohol.

Addiewell chemical works

Employing 700 workers, Young found that the heavily polluted river could not be used for production purposes, and so was forced to drive his own water wells. At peak production, the plant consumed annually:[8]

- 526,000,000 imperial gallons (2.39×109 l; 632,000,000 US gal) of water

- 73,210 long tons (74,380 t) of coal, used also to power the 280 horsepower (210 kW) steam engines

- 134,000 long tons (136,000 t) of bituminous shale

- 2,940 long tons (2,990 t) of sulphuric acid

- 628 long tons (638 t) of caustic soda

In output, it produced:[8]

- 2,285,400 imperial gallons (10,390,000 l; 2,744,700 US gal) of illuminating oil

- 172,000 imperial gallons (780,000 l; 207,000 US gal) of lubricating oil

- 120,000 imperial gallons (550,000 l; 140,000 US gal) of naphtha

- 1,300 long tons (1,300 t) of paraffin

- 585 long tons (594 t) of ammonium sulfate, a fertilizer

The plant burnt its own liquid waste, the coal ash was used to repair local roads, while the 11,000 long tons (11,000 t) of shale waste was disposed by conveyor belt to local waste heaps.[8] Due to the volume of materials required to enable the works, Young in part sponsored the Caledonian Railway's Cleland and Midcalder Line.

In 1866 Young sold the company to Young's Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company.[4] Although the nearby Woodmuir colliery had supplied coal to the works, its workforce was excluded from living in the village until Young sold the company.[7]

When the reserves of torbanite eventually gave out, the company moved on to pioneer the exploitation of West Lothian's oil shale deposits, the only workable deposits in Europe outside Russia, if not so rich in oil as torbanite. By the 1900s nearly 2 million tons of shale were being extracted annually across West Lothian, employing 4,000 men.[4]

The refinery closed in 1921, the associated candle works in 1923.[8] The reduction in workers brought about the demolition of some of the early housing.[7] The paraffin works were due to close pre-World War II, but were saved by the onset of hostilities by virtue of reducing imports. After the paraffin works closed in 1956, the site remained derelict until the last buildings were cleared in 1986.[8]

Present

Addiewell has a combined school, comprising St Thomas' RC and Addiewell Primary and an on site community centre, constructed to compliment the schools and provide a function hall for all local groups.

Addiewell has three shops, one pub and a community facility/softplay/gym called The Pitstop. The local football team is called Loganlea United.

The prison, built to hold up to 800 maximum security prisoners on the site of the former chemical works, opened in December 2008.

Representation

Addiewell is part of the Livingston UK Parliament constituency, currently represented by Graeme Morrice of the Scottish Labour Party.

Addiewell is part of the Almond Valley constituency in the Scottish Parliament, represented by the locally raised Angela Constance of the Scottish National Party.

Transport

Developed as part of the Caledonian Railway's Cleland and Midcalder Line, Addiewell railway station is now on the Shotts Line from Glasgow Central to Edinburgh Waverley. With an hourly service in each direction, it has recently been upgraded to support the new prison.

People from Addiewell

- Angela Constance - SNP politician, MSP

- Jimmy McGuigan - footballer

References

- Alistair Findlay (2010) Shale Voices Luath Press Ltd (ISBN 978-1906307110) - memoir of the shale oil industry

Notes

- ↑ The Online Scots Dictionary.

- ↑ List of railway station names in English, Scots and Gaelic Archived January 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. - NewsNetScotland

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Russell, Loris S. (2003). A Heritage of Light: Lamps and Lighting in the Early Canadian Home. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3765-8.

- 1 2 David Bremner (1869). "The Industries of Scotland: Their Rise, Progress and Present Condition". Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- ↑ "Addiewell". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 3 "Addiewell". scottishshale.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Addiewell Chemical Works". scottishshale.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Addiewell. |