Alderley Edge Mines

|

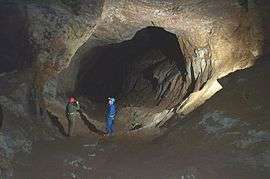

Passage in West Mine | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Alderley Edge Location in Cheshire | |

| Location | Alderley Edge |

| County | Cheshire |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°17′46″N 2°12′43″W / 53.296°N 2.212°WCoordinates: 53°17′46″N 2°12′43″W / 53.296°N 2.212°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Copper Lead Cobalt |

| History | |

| Opened | Early Bronze Age |

| Closed | 1920s |

| Owner | |

| Company | National Trust |

The Alderley Edge Mines are located on the escarpment in Alderley Edge, Cheshire. Archaeological evidence indicates that copper mining took place here during Roman times and the Bronze Age, and written records show that mining continued here from the 1690s up to the 1920s. The site was the location of the Alderley Edge Landscape Project and the Pot Shaft Hoard.

Many of the mines are owned by the National Trust. The Derbyshire Caving Club have leased the access rights, and they continue to explore and search for areas of mining that have been closed for centuries.

Location and geology

The mines are located on the escarpment in Alderley Edge, Cheshire.[1] The area has a mix of Jurassic Lias material, along with Triassic salt formations, Mercia Mudstone Group material, pebble beds and Sherwood Sandstone Group material, and Westphalian and Namurian components from the Carboniferous era.[2]

History

Bronze Age

In the 19th century, crudely shaped stones were found in the bottom of old workings and were thought to be Bronze Age hammer stones.[3] A wooden shovel was found and recorded in 1878.[4] The findings from the 1878 investigation were written up by Roeder and Graves;[5][6] these added to the theory of Bronze Age working that there was a possibility of Roman mining. The picture was transformed in 1993 when a wooden shovel was rediscovered by Alan Garner. The shovel was carbon-dated to around 1780 BC.[7] Subsequently, the Alderley Edge Landscape Project was established, and excavation around Engine Vein revealed what are believed to be Bronze Age smelting hearths dating to around 2000 BC.[8]

Roman mining

Roman mining was considered unlikely until the finding in 1995 of a 4th-century Roman coin hoard (the "Pot Shaft Hoard") in an abandoned shaft at Engine Vein mine.[9] This dated the shaft to the 4th century and its regularity and depth suggested that the Romans may well have worked it. An archaeological excavation was undertaken by Derbyshire Caving Club members supervised by the Alderley Edge Landscape Project archaeologists and, at the bottom, timbers were revealed which were carbon-dated to the last century BC. Given that they were heartwood from cut timbers, the dating cannot be precise and the shaft is now believed to be Roman in origin. The passage from the shaft to the Vein was driven from the direction of the shaft and resembles other Roman workings in the United Kingdom, such as at Dolaucothi, and in Germany, such as at Wallerfangen.

Between the Roman working and 1690, there is scant evidence of mining except a reference to "myne holes"[10] which cannot be relied on as evidence of mining in progress.

17th and 18th centuries

From 1693[11] to the mid-19th century, various people are reported to have explored the Edge for copper and work was done at Saddlebole, Stormy Point, Engine Vein and Brinlow.[12] It is likely that the near-surface sections of Wood Mine were investigated during this period. One operator of note was Charles Roe of Macclesfield, who worked the mines from 1758 to 1768 before moving to Anglesey on the discovery of major deposits of copper at Parys Mountain.[13]

Early 19th century

Apart from Roe, the history of working up to 1857 is patchy. The best recorded period was between about 1805 and 1815 when a company of local men including a Derbyshire miner, James Ashton, tried to exploit the mines for lead. During the course of their work, they identified the presence of cobalt which was in demand during the Napoleonic blockade of supplies.[14] Evidence in the field points to the working of a series of mines on a north-south fault running from Saddlebole to Findlow Hill Wood. Some parts of Engine Vein and possibly West Mine appear to have been excavated at this time. The work ended when the price of cobalt fell. The leases for the period tell the story for Ashton who sacrificed his salary for his share in the company, but even lost this when the company called for more capital than he could provide – and yet he was the man down the mine doing the work.[15]

Late 19th century

In 1857, a Cornish man, James Michell, started work at West Mine[16] and moved on in the 1860s to Wood Mine and Engine Vein.[17] His company lasted 21 years (the length of the lease) although Michell died in an accident in the mines in 1862.[18] During this working period, nearly 200,000 tons of ore were removed yielding 3,500 tons of copper metal. The mines closed in 1877 and the Abandonment Plan of 1878 shows all the workings open at that date. This period saw the mining of West Mine and Wood Mine and the reworking of Engine Vein, Brinlow, Doc Mine and other smaller mines on the Edge.[19][20][21]

20th century

There were some limited and unsuccessful attempts to re-open the mines in 1911,[22] during the First World War, and shortly after.[21] However these ended in the 1920s[23] in a sale of equipment in 1926.[21] From the 1860s onwards, there have been many thousands of visitors to the mines, many – including the earliest – with good lighting and experienced leaders. However, many other visitors, especially between 1940 and 1960, were ill-equipped and unprepared. This led to a series of accidents, which included four fatalities. This included two deaths at West Mine in 1929.[24] The West and Wood Mines were finally blocked in the early 1960s.[25] In 1969, the Derbyshire Caving Club obtained permission from the National Trust (the owners) to re-open Wood Mine and since then much has been found by excavation and exploration, and thousands of people have visited the mines in supervised groups. Since 1969, more mines have been re-opened than were known to exist at the time and all the mines have been professionally mapped by the Derbyshire Caving Club.[20] From 1995 to 2005, a major investigation was undertaken by the Manchester Museum in conjunction with the National Trust, the Caving Club and many others resulting in two significant publications covering the archaeology[8] and wider history of Alderley Edge.[10]

Mines

A number of different mines are located at Alderley Edge. The Mottram St Andrew mine also has connections with the Alderley Edge mines.[1]

Brynlow Mine

Engine Vein is around 300 metres (980 ft) long and 25 metres (82 ft) deep, at an altitude of 155 metres (509 ft). It is one of the earlier mines, with hand picked tunnels, that connects to the Hough Level.[1]

Cobalt Mine

Engine Vein is around 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) long, 16 metres (52 ft) deep, and is at an altitude of 190 metres (620 ft). These mines start at the Engine Vein and run to the current location of the car park.[1]

Engine Vein

Engine Vein is a 750 metres (2,460 ft)-long, 60 metres (200 ft)-deep vertical vein mine, at an altitude of 195 metres (640 ft). It connects to the Hough Level.[1]

Hough Level

The Hough Level is a connecting tunnel that links the Brynlow Mine, the Engine Vein and Wood Mine. It is 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) long and is at an altitude of 135 metres (443 ft).[1]

New Venture

The New Venture mine is located close to West Mine, and is at an altitude of around 145 metres (476 ft).[1]

Pillar and Doc Mines

The Pillar and Doc mines are small, shallow mines near Stormy Point. Between them lie bronze age mines. They are around 50 metres (160 ft) long, 10 metres (33 ft) deep, and are at an altitude of 165 metres (541 ft).[1]

Twin Shafts

Open cast mines on Stormy Point, the Twin Shafts are around 10 metres (33 ft) deep, and are at an altitude of 170 metres (560 ft).[1]

West Mine

West Mine is on multiple levels, and is mostly made up of 19th century tunnels. It is around 10,000 metres (33,000 ft) long, and 50 metres (160 ft) deep, at an altitude of 145 metres (476 ft).[1] It was open for day trips in the 1920s, until two young adults lost their way in the mine in 1929, and their bodies were discovered by chance several months later.[24]

Wood Mine

Wood Mine mostly consists of 19th century tunnels. It is around 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) long, and 30 metres (98 ft) deep, at an altitude of 160 metres (520 ft).[1]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alderley Edge Mines. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "List of Alderley mines". Derbyshire Caving Club. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ "New Historical Atlas of Cheshire". Keele University. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Boyd-Dawkins, W. (1876). On the Stone Mining Tools from Alderley Edge. Jour. Anthropological Inst. G.B. and Ireland, Vol. V, pp 2-5.

- ↑ Sainter, J.D. (1878). The jottings of ... some rambles round Macclesfield. Swinnerton and Brown, Macclesfield.

- ↑ Roeder, C. (1901). Prehistoric and subsequent mining at Alderley Edge, with a sketch of the archaeological features of the neighbourhood. Trans. Lancs. Cheshire Antiquarian Soc. Vol. 19, pp 77–118.

- ↑ Roeder, C.; Graves, F.S. (1905). Recent archaeological discoveries at Alderley Edge. Trans. Lancs. Cheshire Antiquarian Soc., Vol. 23, pp 17–2.

- ↑ Garner A.; Prag A.J.N.W.; Housley R. (1993). The Alderley Edge Shovel, An Epic in three Acts. Current Archaeology. (137) pp 172-175.

- 1 2 Timberlake, S.; Prag, A.J.N.W. (2005). The Archaeology of Alderley Edge. British Archaeological Reports No 396. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges Ltd. ISBN 1 84058 007 0.

- ↑ Nevell, Michael (December 1996). The 'Pot Shaft' Hoard, Alderley Edge, Cheshire. Coins in Context: the controlled micro-excavation of a fourth-century Roman coin hoard. Final Report. University of Manchester Archaeological Unit.

- 1 2 Prag (editor), A.J.N.W. (2016). The Story of Alderley: Living with the Edge. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 360. ISBN 9780719091711.

- ↑ Bennett, J.H.E.; Dewhurst, J.C. (1940). Quarter Sessions Records ... for the County Palatine of Chester 1559-1760. The Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. pp. 195–197.

- ↑ Stanley, L.D. (1843). Alderley Edge and its Neighbourhood. Didsbury: J. Swinnerton, Macclesfield. Reprinted 1972, E. J. Morten.

- ↑ Bentley Smith, D. (2005). A Georgian Gent & Co. - The Life and Times of Charles Roe. Ashbourne: Landmark Publishing. ISBN 1-84306-175-9.

- ↑ Bakewell, Robert (1811). "Account of a Cobalt Mine in Cheshire". Monthly Magazine. 31 (209): 7–9.

- ↑ Anon (1808). "Indenture between (1) Ashton, (2) Bury and Dodge and (3) Jarrold".

- ↑ Higgs, Samuel (15 October 1858). "On the Alderley Edge Copper Mines". Royal Cornwall Gazette: 7.

- ↑ Osborne, Stephen (24 October 1864). "Report". The Mining Journal.

- ↑ Anon (29 November 1862). "Fatal Accident at Alderley". Fatal Accident at Alderley.

- ↑ Carlon, Chris J (1979). The Alderley Edge Mines. Manchester: Sherratt & Son.

- 1 2 Carlon, Chris J; Dibben, Nigel J (2012). The Alderley Edge Mines. Nantwich: Nigel Dibben. ISBN 978 1 78280 015 6.

- 1 2 3 Warrington, Geoffrey (1981). "The Copper Mines of Alderley Edge and Mottram St Andrew, Cheshire". Jour. Chester Arch. Soc. (64): 47–73.

- ↑ Anon (17 February 1911). "Alderley Edge Copper Mines - work commenced". Alderley and Wilmslow Advertiser.

- ↑ Sinclair Ross, James (7 June 1920). "Improvements in the obtainment of sulphate of copper, from ores containing copper. Patent 1920 No 143,973": pp 1–3.

- 1 2 Whitehouse, Bill (1 November 2013). "The history of cave rescue before the 1959 'Neil Moss Tragedy'" (PDF). Mountain Rescue England and Wales. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Jones, William Francis (1961). The Copper Mines of Alderley Edge. Manchester: Privately published.