All Partners Access Network

| |

| Abbreviation | APAN |

|---|---|

| Formation | June 3, 1997 |

| Purpose | Humanitarian Aid, Disaster Management, Security Cooperation |

| Headquarters | Honolulu, Hawaii |

| Website | https://www.apan.org |

Formerly called | Asia-Pacific Area Network |

All Partners Access Network (APAN), formerly called Asia-Pacific Area Network, is a United States Department of Defense (USDOD) social networking Website used for information sharing and collaboration.[2] APAN is the premier collaboration enterprise for the USDOD.[3] The APAN network of communities fosters multinational interaction and multilateral cooperation by allowing users to post multimedia and other content in blogs, wikis, forums, document libraries and media galleries. APAN is used for Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief, Exercise Planning, Conferences and Work Groups.[4] APAN provides non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and U.S. partner nations who do not have access to traditional, closed USDOD networks with an unclassified tool to communicate.[5]

History

1997–2004

The origins of APAN can be traced back to the Virtual Information Center (VIC)[6] which was created at Camp Smith in Honolulu, Hawaii. The VIC was established as an open source, information network designed to provide timely crisis-driven information to command decision makers.[7] Admiral Dennis Blair, the U.S. Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Command, believed that genuine security within the region comes only when nations share dependable expectations of peaceful change, and act in concert to address common challenges.[8] He maintained that armed forces, in conjunction with diplomatic efforts, should cooperate.[9] It was at this same time U.S. coalition partners were seeking greater interoperability within the USPACOM Area of Responsibility (AOR).[10] As a result, APAN was created in March 2000[11] to provide partner nations with a non-dot-mil (.mil), unclassified link into the Virtual Information Center to establish a way to communicate world-wide.[12]

Admiral Dennis C. Blair's objective was to further the USPACOM Regional Security Cooperation objectives using collaborative, online tools.[13] Through Admiral Blair's direction, the Asia-Pacific Area Network was utilized to encourage cooperation on common tasks, from search and rescue to peacekeeping operations to promoting collaboration across the Pacific.[14] The goal was to collaborate, cooperate and coordinate with USPACOM foreign partners and NGOs.[15]

Admiral Blair, collaborating with Senator Daniel K. Inouye, received congressional funding through the Asia-Pacific Regional Initiative Fund (APRI) to further develop APAN.[16]

As development of Asia Pacific Area Network continued, partnering nations began to increase situation awareness of events and developments within the Asia-Pacific region.[17] APAN provided mutual benefit by providing capabilities, information and shared results instantly with USPACOM foreign counterparts and NGOs.[18] APAN played a major role in Operation Unified Assistance to assist relief efforts to the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami. During this humanitarian response militaries from multiple countries worked with NGOs in Thailand. APAN was utilized to assist in cooperation of these efforts to assist more than 12,600 USDOD personnel, foreign military partners and NGOs that were involved in the relief effort.

2005–2009

As APAN grew, other HADR exercises and planning sessions utilized APAN. In 2005, the USPACOM APAN (J08) team merged to form the J7 Training Directorate.[19]

On April 1, 2007, in a report to the U.S. Congress on the Implementation of U.S. DOD Directive 3000.05 Military Support for Stability, Security, Transition and Reconstruction (SSTR) Operations supporting U.S. National Security Presidential Directive 44 (NSPD-44), Management of Interagency Efforts Concerning Reconstruction and Stabilization Operations,[20] U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said, "Exercises and security cooperation activities such as Balikatan and Cobra Gold, support to the Global Peace Operations Initiative, bilateral activities with regional allies, and cooperative planning through U.S. Pacific Command’s 33-nation Multi-national Planning and Augmentation Team are further strengthening the relationships essential to stability operations. The value of these relationships and capabilities was demonstrated in tsunami, earthquake, and landslide relief operations, as well as in supporting activities for Operation Enduring Freedom - Philippines. To improve regional stability operations coordination and interoperability, U.S. Pacific Command sponsors the Asia Pacific Area Network (APAN), an unclassified internet-based collaboration portal for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations. APAN supports U.S. Pacific Command’s theater strategy and improves coordination among government agencies and international organizations. U.S. Pacific Command will continue to expand its interagency and multi-national approach to stability operations through exercises, workshops, and expanded initiatives."[21]

In 2009, APAN was chosen by the Oversight Executive Board as the platform for the Transnational Information Sharing and Collaboration (TISC) Joint Capability Technology Demonstration (JCTD).[19] Once this occurred, APAN was being utilized by individuals outside of the USPACOM AOR and changed its name to All Partners Access network.[22][23]

2010–2015

After several years of developing APAN,[24] in January 2010, the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) setup an APAN Community to assist more than 500 organizations looking to coordinate efforts for the 2010 Haiti Earthquake within USSOUTHCOM.[25] APAN was utilized to support Operation Unified Response to coordinate NGOs, foreign governments. private individuals and humanitarian assistance. Users utilized APAN to share situation reports, imagery and other crucial statistics with the humanitarian aid community. Over 1,400 users, including the Red Cross and smaller relief organizations communicated with one another using APAN. to relieve the suffering in Haiti.[26] In an interview conducted with the CTO of DISA by Defense Systems, Dave Mihelcic, states "One of the things we learned...is that you can't always understand who your partners are. One night I was on APAN, watching Haiti relief being coordinated by a U.S. Southern Command operator, and someone popped in and said, 'I'm the owner of a construction business in Biloxi [Miss.] and I have four qualified bulldozer operators, and if you can arrange transportation to Haiti, they can participate in the relief.' And they were able to coordinate that."[27]

In 2011, the US DOD announced a new Unclassified Information Sharing Service (UISS) as an enterprise service centrally funded for all Combatant Commands (COCOMs) to use with mission partners in their respective AORs.[28]

Technology

APAN users can select between two platforms based on their community need: Telligent or SharePoint. Added to APAN in 2010, Telligent provided APAN users a more social opportunity and uses blogs, wikis, forums and media galleries. In 2013, APAN added SharePoint as a secondary platform for those users who were looking for more structured content[29] using document libraries and lists.

Additional features

Chat

APAN added chat services to support HADR events and exercises for users to collaborate in real-time from a browser in 2014.[29][30]

Conferencing

APAN added Adobe Connect to facilitate real-time audio and video conferencing to assist with online training and learning in 2000.[29][31]

Maps and GIS

In 2012, APAN adds Mapping and GIS capabilities to support collaboration.[29][32][33] Mapping capabilities are enhanced on October 31, 2015.[34]

Mobile

On October 31, 2015, APAN upgrades Telligent platform to support responsive design.[34]

Translation

In 2014, APAN enhances translation tools across APAN to be able to communicate with foreign partners using multiple languages.[29][35]

Technology releases

| Version | Date | Update[36] |

|---|---|---|

| APAN 1.0 | 1999 | HTML Code |

| APAN 2.0 | 2001 | Active Server Pages (ASP) |

| APAN 3.0 | 2003 | Lotus Quick Place |

| APAN 4.0 | 2004 | Dot Net Nuke |

| APAN 5.1 | 2007 | Windows Share Point Services |

| APAN 5.2 | 2009 | Telligent Community Server added |

| APAN 5.3 | 2010 | Telligent Web update |

| APAN 6.0 | 2011 | Telligent Web update |

| APAN 6.5 | 2012 | Enterprise SharePoint 2010 added |

| APAN 7.0 | 2014 | Telligent 7.0 |

| APAN 8.0 | 2015 | Telligent 8.5[34] |

Impact

Global communication and collaboration impacts

Cobra Gold

An Asia-Pacific military exercise held annually in Thailand, utilized APAN[37] for emergency notifications during the 2008 Cobra Gold exercise.[38] Partnering with AtHoc IWSAlerts, through USPACOM, the U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC) led operators from the Joint Task Force protection teams throughout Thailand using the emergency alerts for critical communication needs during practice disaster relief efforts.[38] Cobra Gold improved coordinated efforts to natural disaster response including the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the Typhoon Haiyan response.[39]

RONNA

Originally developed on Harmonie Web, RONNA[40] was moved to APAN in 2011.[41] RONNA[40] provided information sharing between partners working to build a peaceful and democratic state in Afghanistan. RONNA's[40] purpose was to provide information gaps that existed between government and NGOs and other Afghan partners.[42][43] "Over thirty communities from organizations including ISAF, USAID, the U.S. Treasury and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan" shared information within the RONNA[44] community of interest.[45]

Endeavor Exercises

APAN has supported the USDOD's program of "Endeavor" exercises: Pacific Endeavor, Africa Endeavor, and Combined Endeavor. These exercises have brought together military representatives from various nations in a region to practice communications in crisis scenarios. Hundreds of communications officers and technicians from around the globe have gathered annually for these events to practice communicating before a crisis strikes and to build relationships beyond cultural boundaries.[47]

Combined Endeavor

Combined Endeavor, the largest command, control, communications and computer interoperability event in the world,[48] used APAN to provide online collaboration for exercise planning and equipment management.[49]

Africa Endeavor

In 2010, for the first time ever, a direct communications link was established between the African Union and units in the field as part of the annual Africa Endeavor 2010 Exercise by using APAN, to allow international military and NGO groups to work together in a neutral online environment.[50] Approximately 40 countries participate in bilingual crisis response exercises using English and French with approximately 1,000 members of the APAN community sharing pictures and files using translation functions that have supplemented the need for interpreters which has expanded participant's ability to overcome language barriers.[51]

Pacific Endeavor - Multinational Communications Interoperability Program (MCIP)

Since 2010, through USPACOM, MCIP has hosted Pacific Endeavor exercises that have brought together partner nation militaries and HADR experts from around the world to develop, test, and improve communication systems across the Pacific.[52] MCIP has used APAN to promote humanitarian communication, for its planning workshops.[53] The planning workshops assisted USPACOM partners and NGOs to plan communication procedures in the event of a natural disasters and to build partnerships.[54] On August 19, 2014, part of an exercise performed through MCIP was for Nepalese amateur radio operators to report earthquake aftershocks to USPACOM using APAN.[55] This practice proved successful as partners around the world knew how to communicate during the 2015 Nepal Earthquake[56] using the bulletin board established on APAN.[57]

CJTF-HOA

In 2014, Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) used APAN forums to conduct collaboration and sharing between scholars, government, NGOs and professionals around the world who were interested in East African Issues. The CJTF-HOA APAN community provided its members chat, file, sharing, geo-data, and translation for situation awareness and knowledge specific to the Horn of Africa.[58][59]

2015 Nepal earthquake

The 7.3 earthquake that shook Nepal damaged various radio antennae and Amateur Radio for emergency operations was down in Nepal and the surrounding area.[60] The Army Military Auxiliary Radio System (MARS) gathered information and statistics on the earthquake and relayed messages around the world to other HAM operators and also posted the information on the NEPAL HADR APAN community of interest [61] for those who were assisting to coordinate relief efforts.[62]

Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) impacts

2010 Haiti earthquake

The 2010 Haiti earthquake was one of the world's deadliest national disasters. Shortly after the earthquake, surviving officials of the government of Haiti made urgent request for United States assistance.[22] APAN was requested to assist as the primary communication hub for the Haiti Earthquake relief efforts for unclassified, nonmilitary information sharing and collaboration.[63] USSOUTHCOM established an APAN community of interest[64] and within three weeks, APAN had more than 1,800 registered users supporting the relief efforts.[65]

Imagery, maps, photos, assessments, situation reports, common operational picture reports, and requests for information were all made available on APAN to support the humanitarian assistance. From the information-management standpoint, the decision to keep the Haiti operations within the unclassified domain enabled information sharing across agencies.[66]

A user on APAN posted, "Sacre Coeur Hospital in Milot, Haiti is appealing for patients. Need coordination to get helos to hospital." Two days later, the hospital reported going from 20 patients to 112 new patients with 12 helicopter landings and 17 foreign doctors assisting the patients; four days later the hospital expanded into a nearby school with 100 more patients with cots and equipment.[67]

2011 Japan earthquake

In March 2011, a public community of interest was created on APAN, Japan Earthquake 2011 Support,[68] in an effort to facilitate information sharing with U.S. Government organizations and NGOs involved in the disaster relief efforts.[69][70][71] A private community, the Virtual Civil Military Operations Center (VCMOC), was set up in order to develop an unclassified Common Operating Picture (COP) and to share information in support of Joint relief operations.[72] Members of the VCMOC were invited by invitation only. Both communities were created on APAN to assist Operation Tomodachi.[73] Operation Tomodachi was the first joint operation in the field for US Forces Japan (USFJ) and Japan Self-Defense Forces (USDF) within the USPACOM AOR.[74] Watchstanders were able to provide Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) and Concept of Operations (CONOPs) via APAN.[75] APAN was used to coordinate travel for United States military families who were evacuating and traveling back to the United States. from Japan.[76] APAN forums provided links for those traveling as well as FAQs.[76] The Yale-Tulane Disaster Resilience Academy created daily briefs to compile information into a format that could be shared through public blogs.[76]

RIMPAC 2012: Operation Restore Chianti

For the first time in RIMPAC’s 41-year history, an HADR component was part of the maritime exercise, with U.S. hospital participation.[77] Hospitals participated in the disaster scenario with helicopter landings, patient transport for patients with simulated injuries.[78] During the fictitious response Operation Restore Chianti,[79] simulated DOD-produced public health messaging, resupply and exercise communications occurred on 800MHz and APAN.[78] The exercise also incorporated crowd-sourced crisis mapping components to simulate the mass influx of social media messages that are produced during a disaster.[79] Volunteers produced and validated over 2,000 incident reports that were funneled into APAN’s map feeds.[79] This shared communication platform for RIMPAC participants was offered by APAN.[80]

RIMPAC 2014: Operation Restore Griffon

APAN was used to increase accessibility and collaboration for the RIMPAC HADR portion of Operation Restore Griffon.[81] The APAN community of interest was designed to provide a space for coordinating requirements and contributions related to a fictitious hurricane response effort during RIMPAC 2014. The United Nations also worked side-by-side with APAN during RIMPAC 2014 using an RSS feed to post information from UNOCHA's Virtual On-Site Operations Coordination Center (VOSOCC) website to APAN. APAN was a conduit for China to be able to participate in RIMPAC for the first time; the U.S. DOD would not allow China access to classified networks that were utilized within the exercise.[82][83] Partnerships started at RIMPAC continue to work on shared procedures for future use.[51]

RIMPAC 2016: Operation Restore Griffon

APAN was used in the RIMPAC - HADR exercise.[84] The exercise simulated humanitarian assistance after a 7.9 earthquake hit the fictitious country of Griffon. Civilian participants included: Hawaii Disaster Medical Assist Team (HDMAT); Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA); Civil-Military Coordination Center (CMCC); United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (US-OCHA); Commander Combined Task Force (CCTF); National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) & Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (USDP). Military participants included: Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF); US THIRDFLT Forces; Canada and various LNO’s from RIMPAC coalition countries.[85]

2013 Philippines typhoon

The global response to Typhoon Haiyan began hours after the storm hit the Philippines on November 8, 2013.[86] USPACOM, in coordination with APAN, launched the Typhoon Haiyan Response Group[87] to provide a centralized location for coordination and communication.[88] APAN was used to provide situation reports on damage.[89] APAN users were able to upload documents, data-sets and files to assist in the relief efforts[90] to decrease response time.[91] Partnering with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, APAN’s mapping tools provided NGA data to automatically federate geo-spatial content[92] which was utilized to provide the maps for infrastructure and agriculture.[93]

Health impacts

2014 Ebola Response Network (ERN)

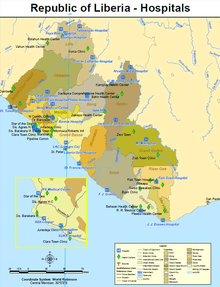

USAFRICOM supported the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) which led the foreign humanitarian assistance efforts for Operation United Assistance. Operation United Assistance was a United States military mission to respond to the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa in September 2014. Through coordination and collaboration, NGOs and the US Military were able to utilize APAN to create the Ebola Response Network,[95] an APAN community of interest.[96] APAN also worked with the National Geospatial-intelligence Agency (NGA) to provide accurate data and maps for mission related efforts using the Ebola Response Network.[95][97] Within the first month of the Ebola Response Network[95] being deployed, it had 600 members sharing updates and announcements, uploading documents and using chat rooms.[98]

Recognition

APAN has been honored by different organizations.

- 2010 - Forrester Groundswell Award: Management Division[99]

- 2011 - Excellence in Intergovernmental Collaboration from The American Council for Technology and Industry Advisory Council (ACT-IAC)[100]

- 2013 - The Computerworld Honors Program; Laureate: Collaboration Finalist[47]

Location

APAN is headquartered at the Pacific Warfighting Center on Ford Island in Honolulu, Hawaii.[101]

References

- ↑ "Pacific Warfighting Center (PWC) - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ↑ Malowany, Isabel (August 17, 2010). "All Partners Access Network (APAN): Your Social Networking Site for Knowledge, Resources and Collaboration". Dialogo-Americas.

- ↑ Carey, Robert (October 2011). "DOD CIO Instruction: APAN Shared Enterprise Service Designation". APAN.org.

- ↑ "Solutions: HA/DR". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ↑ "About Us". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ↑ Trevorton, Gregory F. (March 3, 2003). Reshaping National Intelligence for an Age of Information (2001 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-521-58096-X.

- ↑ Hayes, Richard; Daly-Hayes, Margaret; Owen, Donald (September 23, 2005). "Humanitarian, Peace, and Reconstruction Operations: The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same" (PDF). Analysis for New and Emerging Societal Conflicts. Retrieved December 24, 2015 – via The International Symposium on Military Operational Research.

- ↑ Valencia, Mark J. "The U.S. Position on Co-operative Maritime Security Frameworks" (PDF). Institute for International Policy Studies.

- ↑ Blair, Dennis C. (August 6, 2001). "Cooperation and Responsibility in Regional Security". East West Center News. Honolulu, HI.

- ↑ "Hearing before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations United States Senate One Hundred Seventh Congress Second Session". US Government Publishing Office. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. April 3, 2002.

- ↑ Forbes, Andrew; Gaffney, Rowena (December 2014). "Royal Australian Navy: Indian Ocean Naval Symposium" (PDF). Royal Australia Navy. Sea Power Center: IONSPHERE. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ↑ Lawlor, Maryann (November 2000). "Pacific Command Builds Electronic Bridges". Signal Magazine – via http://www.afcea.org/.

- ↑ Blair, Dennis C. (March 8, 2001). "USPACOM Before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense on Fiscal Year 2002 Posture Statement".

- ↑ Watson, Cynthia (2011). Combatant Commands: Origins, Structure, and Engagements. ABC-Clio. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-313-35433-5.

- ↑ "Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations" (PDF). U.S. Joint Publication. March 17, 2006. Retrieved June 24, 2011 – via Joint Electronic Library.

- ↑ "Hearing before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations United States Senate One Hundred Seventh Congress Second Session". US Government Publishing Office. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. April 3, 2002.

- ↑ "Hearing before the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific of the Committee on International Relations House of Representatives One Hundred Eighth Congress: First Session". Hathi Trust Digital Library. 108-52. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. June 26, 2003. p. 20.

- ↑ "Hearing before the Subcommittee on Asia and The Pacific of the Committee on International Relations House of Representatives One Hundred Eighth Congress: First Session". Hathi Trust Digital Library. 108-52. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. June 26, 2003. p. 34.

- 1 2 "Milestones, Collaborative Solutions for the DOD". All Partners Access Website. APAN Support. October 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ↑ DC, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE WASHINGTON (2007-04-01). "Report to Congress on the Implementation of DoD Directive 3000.05 Military Support for Stability, Security, Transition and Reconstruction (SSTR) Operations".

- ↑ "Defense Technical Information Center". DOD Public Access Search. Office of the Secretary of Defense

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. April 1, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. April 1, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2015. - 1 2 Cecchine, Gary; Morgan, Forrest; Wermuth, Michael; Timothy, Jackson; Gereben-Schaefer, Agnes; Stafford, Matthew (2013-01-01). "The U.S. Military Response to the 2010 Haiti Earthquake". www.rand.org. The Rand Corporation. ISBN 9780833080752. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- ↑ "Other Group Books". openvce.net. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ↑ Pierce, David (January 21, 2010). "Pentagon's Social Network Becomes Hub for Haiti Relief". Danger Room. Wired Magazine.

- ↑ "Defense launches online system to coordinate Haiti relief efforts". Nextgov. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ Hodge, Nathan (January 22, 2010). "Military May Crowdsource Haiti Relief". WIRED. Wired Magazine.

- ↑ "DISA's Dave Mihelcic discusses to speed tech deployment in the defense enterprise environment -- Defense Systems". defensesystems.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Files - Resources - Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Tools: Chat". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Tools: Connect". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Hawaii Pacific GIS Conference 2012: Real-Time Data Acquisitions - Soc…". 2012-03-16.

- ↑ "Tools: Maps". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- 1 2 3 "* APAN 8.0 - Knowledge Base - Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ↑ "Tools: Translate". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Files - Resources - Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- ↑ "APAN - All Partners Access Network".

- 1 2 "AtHoc IWSAlerts Achieves "Positive Military Utility" Rating by U.S. Army Pacific and U.S. Pacific Command after Use in Cobra Gold Exercise in Thailand - AtHoc - Networked Crisis Communication". www.athoc.com. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ↑ Hayton, Bill (2014-09-11). The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia. Yale University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780300189544.

- 1 2 3 https://ronna.apan.org/

- ↑ Tate, Austin. "OpenVCW". Open Virtual Collaboration Environment. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ "RONNA: an APAN COI". RONNA. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Case Study: RONNA". APAN. All Partners Access Network. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Case Study: Afghan Information Sharing (RONNA)".

- ↑ "Case Study: Afghan Information Sharing (RONNA)". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ Lamb, Steven. "U.S. AFRICOM Photo". www.africom.mil. US AFRICOM Public Affairs

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Retrieved 2015-12-24. - 1 2 "Computerworld Honors 2013: Tech projects that are changing the world". Computerworld. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ Affairs, U.S. EUCOM Public. "Exercises and Operations". www.eucom.mil. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ↑ "Case Study: Combined Endeavor". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ↑ Crawley, Vince. "In First-Ever Communications Test, AFRICOM Assists African Union Peace Ops Center". www.africom.mil. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- 1 2 Coutinho, Lara (April 2015). "APAN: How the DOD Gets Social" (PDF). Liaison. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ↑ Donnelly, Lt. Theresa (January 5, 2012). "Pacific Endeavor: Improving Interoperability and Building Relationships". USPACOM. USPACOM Blog. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Salevski, LCDR Paul (August 2014). "MCIP Annual Cycle". Slideplayer. USPACOM: Pacific Senior Communicators Meeting 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Exercise Pacific Endeavor 2015 Highlight Video". YouTube. dvidshub. September 10, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Pacific Endeavor-14: Exercise Stresses International Cooperation". AARL.org. The National Association for Amateur Radio. August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Pacific Partners Prove Communication Key to Disaster Response". Relief Web. Government of the United States of America. September 8, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Damron, Jim (September 6, 2013). "Pan Pacific Rescue Radio Exercise Deemed an Unqualified Success". Amateur Radio NewlineT. Charleston, West Virginia. Retrieved December 2014 – via arnewline.org. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Observation Report: Combined Joint Task Force Horn of Africa" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center. Center for Army Lessons Learned. November 2014.

- ↑ Leslie, Staff Sgt. Carlin (November 17, 2014). "CJTF-HOA Fusion Action Cells build Partnerships across Africa". USARFRICOM. Stuttgart, Germany.

- ↑ Holloway, John (April 26, 2015). "Nepal Amateur Radio station 9N1AA is damaged". All Partners Access Network. Nepal HADR COI.

- ↑ https://community.apan.org/hadr/pacom-hadr/nepal_hadr/

- ↑ "Nepal Amateur Radio Earthquake Relief Response Suspended Again". AARL. The National Association for Amateur Radio. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ↑ Cecchine, Gary; Morgan, Forrest E.; Wermuth, Michael A.; Jackson, Timothy; Schaefer, Agnes Gereben; Stafford, Matthew (2013). The U.S. Military Response to the 2010 Haiti Earthquake. Washington, D.C.: Rand. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8330-8075-2.

- ↑ "Case Study: Humanitarian Assistance for Haiti". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- ↑ King, Dennis (October 2010). "The Haiti Earthquake: Breaking New Ground in the Humanitarian Information Landscape". Humanitarian Exchange Magazine. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ↑ Schear, James (July 28, 2010). "National Security, Interagency Collaboration, and Lessons from SOUTHCOM and AFRICOM". U.S. Government Publishing Office. Washington, D.C.: Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ↑ Giles, Jerry. "APAN: Everything is a Situational Update". SlidePlayer. APAN. pp. 16–17. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Japan Earthquake 2011 Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "Yale / Tulane ESF-8 Planning and Response Program Special Report" (PDF). Louisiana VOID. Louisiana Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters. March 15, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ "APAN Community: Japan Earthquake 2011 - CrisisWiki". crisiswiki.referata.com. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ French, Dan; Mosinski, David (February 11, 2013). "Strategic Lessons in Peacekeeping & Stability Operations" (PDF). www.pksoi.org. U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ "SOLLIMS Sampler Volume 6, Issue 2, Foreign Humanitarian Assistance Volume 6, Issue 2". Joomag. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ Mackenzie, David (April 25, 2011). "USPACOM VTC Operation Tomodachi Lessons Learned" (PDF). Cisco Strategy Docs. USPACOM. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Japan Chair Platform: Operation Tomodachi in Miyagi Prefecture: Success and Homework | Center for Strategic and International Studies". csis.org. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "CHIPS Articles: Japan's "3/11" Triple Disaster". www.doncio.navy.mil. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- 1 2 3 "Case Study: Tsunami relief work in Japan". apan.org.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Retrieved 2015-12-22. - ↑ Cole, William (July 21, 2012). "Military, hospitals collaborate during 'tsunami' at RIMPAC". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- 1 2 Estribou, Adria (July 2012). "Healthcare Association of Hawaii: Emergency Services" (PDF). RIMPAC 2012 Humanitarian Assistance Disaster Response (HADR). Retrieved December 28, 2015 – via HAH.org Pressroom.

- 1 2 3 "Case Study: Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC)". www.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ↑ "Emergency Journalism | toolkit for better and accurate reporting". emergencyjournalism.net. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ↑ "SOLUTE Participates in M2I2 | Solute". solute.us. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ↑ Tiezzi, Shannon (June 11, 2014). "A 'Historic Moment': China's Ships Head to RIMPAC 2014". Know the Asia-Pacific – via thediplomat.com.

- ↑ Jackson, Van; Rapp-Hooper, Mira; Scharre, Paul; Krejsa, Harry; Chism, Jeff (March 2016). "Networked Transparency: Constructing a Common Operational Picture of the South China Sea" (PDF). Center for a New American Security. Asia-Pacific Security Program. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "DISA's UISS-APAN System Supports Rim of the Pacific Exercise". The Department of the Navy's Information Technology Magazine. August 3, 2016 – via CHIPS.

- ↑ "RIMPAC 2016 Uses APAN as the Primary Disaster Relief Information Sharing Platform - Press Releases - Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Tangredi, Sam (2015-07-15). The U.S. Naval Institute on International Naval Cooperation. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612518633.

- ↑ https://community.apan.org/support/b/blog/archive/2013/11/08/typhoon-haiyan-response-community

- ↑ "Typhoon Haiyan Response Community - News & Updates - Support - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ↑ "Haiyan Response and Recovery Still Challenging". www.pdc.org. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ↑ Chan, Jennifer (December 22, 2014). "Capturing Real-Time Data in Disaster Response Logistics" (PDF). Department of Industrial Engineering and management Sciences. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ "STRIKFORNATO | Forging a Global Network of Navies". sfn.nato.int. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ↑ "NGA Creates Website to Support Ebola Relief Efforts : Geospatial Solutions". geospatial-solutions.com. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "Ebola Response Network - APAN Community". community.apan.org. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- 1 2 3 https://community.apan.org/apcn/ern/

- ↑ Brewin, Bob (October 9, 2014). "US Army Will Provide Wi-Fi for NGOs in the Fight Against Ebola". Nextgov. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "NGA supports Ebola relief efforts, provides data to public". www.nga.mil. October 23, 2014. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "Responding to the Ebola Outbreak: Connecting People, Capabilities, and Resources" (PDF). Booz Allen Hamilton.

- ↑ "Forrester Research : Marketing : Forrester Research Announces 2010 Forrester Groundswell Award Winners For Excellence In Social Technologies". www.forrester.com. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "ACT-IAC Announces 2011 Excellence.gov Award Finalists". Fairfax, Virginia: ACT-IAC. February 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Dept of Defense - All Partners Access Network (APAN)". www.linkedin.com. Retrieved 2015-12-18.