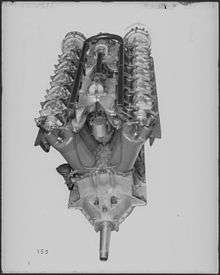

Liberty L-12

| Liberty L-12 | |

|---|---|

| |

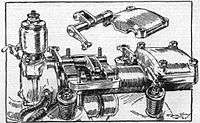

| Liberty L-12 aircraft engine | |

| Type | Piston aero engine |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lincoln, Ford, Packard, Marmon, Buick |

| Designed by | Jesse G. Vincent and Elbert J. Hall |

| First run | about 1917 |

| Number built | 20,748 |

| Variants | Liberty L-4, Liberty L-6, Liberty L-8 |

The Liberty L-12 was an American 27-litre (1,649 cubic inch) water-cooled 45° V-12 aircraft engine of 400 hp (300 kW) designed for a high power-to-weight ratio and ease of mass production. It was succeeded by the Packard 1A-2500.

Development

In May 1917, a month after the United States had declared war on Germany, a federal task force known as the Aircraft Production Board summoned two top engine designers, Jesse G. Vincent (of the Packard Motor Car Company of Detroit) and Elbert J. Hall (of the Hall-Scott Motor Co. in Berkeley, California), to Washington, D.C.

The two left their positions at the Fageol Motors Co., putting an end to the short production of the most luxurious automobile of the period.[1] They were given the task of designing as rapidly as possible an aircraft engine that would rival if not surpass those of Great Britain, France, and Germany. The Board specified that the engine would have a high power-to-weight ratio and be adaptable to mass production.

The Board brought Vincent and Hall together on 29 May 1917 at the Willard Hotel in Washington, where the two were asked to stay until they produced a set of basic drawings. After just five days, Vincent and Hall left the Willard with a completed design for the new engine,[2] which had adopted, almost unchanged, the single overhead camshaft and rocker arm valvetrain design of the later Mercedes D.IIIa engines of 1917-18.

In July 1917, an eight-cylinder prototype assembled by Packard's Detroit plant arrived in Washington for testing, and in August, the 12-cylinder version was tested and approved.

Production

In the fall of 1917, the War Department placed an order for 22,500 Liberty engines, dividing the contract between the automobile and engine manufacturers Buick, Ford, Cadillac, Lincoln, Marmon, and Packard. Hall-Scott in California was considered too small to receive a production order. Manufacturing by multiple factories was facilitated by its modular design.[3]

Ford was asked to supply cylinders for the new engine, and rapidly developed an improved technique for cutting and pressing steel which resulted in cylinder production rising from 151 per day to over 2,000, Ford eventually manufacturing all 433,826 cylinders produced, and 3,950 complete engines.[4] Lincoln constructed a new plant in record time, devoted entirely to Liberty engine production, and assembled 2,000 engines in 12 months. By the time of the Armistice with Germany, the various companies had produced 13,574 Liberty engines, attaining a production rate of 150 engines per day. Production continued after the war, for a total of 20,478 engines built between July 4, 1917 and 1919.[5]

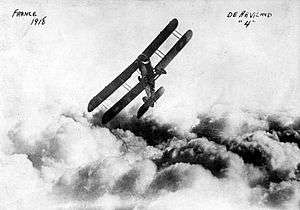

Although it is widely reported otherwise, a few Liberty engines did see action in France as power for the American version of the Airco DH.4.[6]

Lincoln production

As the United States entered World War I, the Cadillac division of General Motors was asked to produce the new Liberty aircraft engine, but William C. Durant was a pacifist who did not want General Motors or Cadillac facilities to be used for producing war material. This led to Henry Leland leaving Cadillac to form the Lincoln Motor Company to make Liberty engines. He quickly gained a $10,000,000 government contract to build 6,000 engines.[7] Subsequently the order was increased to 9,000 units, with the option to produce 8,000 more if the government needed them.[8] More than 16,000 Liberty engines were produced during the calendar year 1918. To November 11, 1918, more than 14,000 Liberty engines were produced.[9] Lincoln had delivered 6,500 of the 400 hp, V-12, overhead camshaft engines when production ceased in January 1919.[10] Durant later changed his mind and both Cadillac and Buick produced the engines.[11]

Design

The Liberty engine was a modular design where four or six cylinders could be used in one or two banks, with the cylinders designed as individual units, each with their own water jacket.

A single overhead camshaft for each cylinder bank operated two valves per cylinder, in an almost identical manner to the inline six-cylinder German Mercedes D.III and BMW III engines, and with each camshaft driven by a vertical driveshaft that was placed at the back of each cylinder bank, again identical to the Mercedes and BMW straight-six powerplants. Dry weight was 844 lb (383 kg).

Fifty-two examples of a six-cylinder version, the Liberty L-6, which very closely resembled the Mercedes and BMW powerplants in overall appearance, were produced but not procured by the Army. A pair of the 52 engines produced were destroyed by William Christmas testing his so-called "Christmas Bullet" fighter.

Variants

V-1650

An inverted Liberty 12-A referred to as the V-1650 was produced up to 1926 by Packard.

The same designation was later applied to the Packard V-1650 Merlin, an engine with nearly identical engine displacement. This was a World War II Packard produced version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin,[12] and is not to be confused with the earlier Liberty-based version.

Allison VG-1410

The Allison VG-1410 was an air-cooled inverted Liberty L-12, with a geared super-charger and Allison epicyclic propeller reduction gear and reduced displacement.[13] (4 5⁄8"x7"=1,411 cuin)

Liberty L-6

A 6-cylinder version of the Liberty L-12, nicknamed the "Liberty Six", consisted of a single bank of cylinders, with the resulting engine bearing a strong external resemblance to both the Mercedes D.III and BMW III straight-six German aviation engines of World War I.

Liberty L-8

An 8-cylinder V engine using Liberty cylinders in banks of four at 90°. (1099.6 ci / 18.02L)

Specifications (Liberty L-12)

Data from Janes's All the World's Aircraft 1919[14]

General characteristics

- Type: 12-cylinder liquid-cooled Vee piston aircraft engine

- Bore: 5 in (127 mm)

- Stroke: 7 in (178 mm)

- Displacement: 1,649.3 in3 (27.03 L)

- Length: 67.375 in (1,711 mm)

- Width: 27 in (685.80 mm)

- Height: 41.5 in (1,054.10 mm)

- Dry weight: 845 lb (383.3 kg)

Components

- Valvetrain: One intake and one exhaust valves per cylinder operated via a single overhead camshaft per cylinder bank

- Fuel system: Two duplex Zenith carburettors

- Fuel type: Gasoline

- Oil system: forced feed, rotary gear pressure and scavenge pumps, wet sump.

- Cooling system: Water-cooled

Performance

- Power output: 449 hp (334.8 kW) at 2,000 rpm (takeoff)

- Specific power: 0.27 hp/cu in (12.4 kW/L)

- Compression ratio: 5.4:1 (Army engines) 5:1 (navy engines)

- Specific fuel consumption: 0.565 pt/hp/hour (0.43 l/kW/hour)

- Oil consumption: 0.0199 pt/hp/hour (0.0152 l/kW/hour)

- Power-to-weight ratio: 0.53 hp/lb (0.87 kW/kg)

Use

Aircraft

The primary use of the Liberty was in aircraft.

- American-built versions of the Airco DH.4

- Airco DH.9A

- Airco DH.10

- Breguet 14 B2 L

- Caproni Ca.60

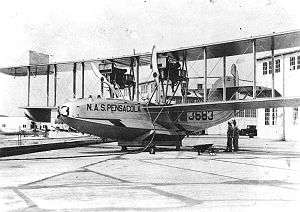

- Curtiss H-16

- Curtiss NC

- Curtiss Carrier Pigeon

- Douglas C-1

- Douglas DT

- Douglas O-2

- Felixstowe F5L

- Fokker T.II

- Handley Page H.P.20

- Witteman-Lewis XNBL

The engine was also used in the RN-1 (Zodiac) blimp.

Automobile

Based on aircraft use the engine provided a good power-to-weight ratio. This made it ideal for use in land speed attempt vehicles.

It was selected for two land speed record attempts.

- Babs (land speed record car), a single engined vehicle

- White Triplex (land speed record car), mounting three liberty's working in tandem

Both attempts set new records, although the first, Babs, resulted in the death of its driver during a further attempt.

Tank

_Tank.jpg)

As early as 1917 the Liberty showed good potential for use in tanks as well as aircraft. The Anglo-American or Liberty Mark VIII tank was designed in 1917–18. The American version used an adaption of the Liberty V-12 engine of 300 hp (220 kW), designed to use cast iron cylinders rather than drawn steel ones. 100 tanks were manufactured at the Rock Island Arsenal in 1919–20, too late for World War I. They were eventually sold to Canada for training in 1940, except for two that have been preserved.

Inter-war, J. Walter Christie combined aircraft engines with new suspension, producing a rapid and highly mobile tank. Using Christie's concept, Russian forces selected and copied the Liberty in the BT-2 & BT-5 Soviet interwar tank (at least one reconditioned Liberty was installed in a BT-5). Demonstration of this tank was witnessed by the British, and Christie's design characteristics were licensed and incorporated into the British A13 design specification.

As World War II loomed, Nuffield, producing British Cruiser tanks, licensed and re-engineered the Liberty for use in the A13 (produced as the Cruiser Mk III) and later Cruiser tanks.

Nuffield Liberty

The Nuffield Liberty tank engine was produced in World War II by the UK car manufacturer Nuffield. It was used in early Cruiser tanks, the Crusader, the Cavalier, and finally Centaur tanks. It was a 27 L (1,649 in3) engine with an output of 340 hp (250 kW), which was eventually to become inadequate for the increasing vehicle weights as the war progressed, and it suffered numerous problems with cooling and reliability.[15]

The Nuffield Liberty ran through multiple versions:[16]

- Mark I, US built engines modified in Britain. Modification incorporated new carburettors and a new induction system from Solex, revision of the crankcase breather, new timing gear, and revised crankshaft end thrust. This produced 340 hp when governed to 1500 RPM with the new carburettors.

- Mark II, British built engines. The air compressor (for starting) wasn't used, and was removed on later engines

- Mark III, IIIA and IIIB, made for the Crusader tank. This reduced the height of the engine to fit the Crusader engine bay. The air compressor was reinstated to enable pneumatically operated braking and steering. To reduce the engine height, the oil pump was redesigned and the water pump was relocated. Significant problems were experienced in desert use (the North African Campaign), and Mk III went through multiple revisions. This included three different chain drive designs for the engine's ancillary cooling fans, a revised valve adjustment mechanism, increased compression ratio, revised oil feeds, and two water pump replacements.

- Mark IV, a revised design providing a shaft drive for cooling fans. This version also changed the air compressor to run at a lower speed.

- Mark IVA, the power was increased to 410 hp by increasing the governor speed to 1700 rpm. This engine also fitted a new intake manifold and carburettor for the Cavalier tank.

- Mark V, redesigned engine producing the same output power for use in the Centaur tank and intended for the Cromwell tank. It revised the oil distribution in the engine, but remained governed to the higher speed of 1700RPM. The design was dropped in favour of the Rolls-Royce Meteor procured by the Tank Board.

In later British tanks it was replaced by the Rolls-Royce Meteor, an engine based on the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine, offering greater engine power.

Nuffield Liberty engines were used in the:

- Cruiser Mk III, British World War II tank - Nuffield Liberty Mk I

- Cruiser Mk IV British World War II tank - Nuffield Liberty Mk II

- Crusader tank British World War II tank - Nuffield Liberty Mk III, IIIA, IIIB, or IV

- Cavalier tank British World War II tank - Nuffield Liberty Mk IVA

- Centaur Tank, an early version of the Cromwell British World War II Tank - Nuffield Liberty Mk V

Survivors

A number of Liberty engines survive in restored operational and static display vehicles. Displays of the engine itself include:

- A 12A is on display at the New England Air Museum at Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[17]

- An operable Liberty V-12 on a static test stand trailer is often run for demonstrations at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome's weekend airshow events.[18]

- A Nuffield Liberty at The Tank Museum, Bovington, UK.

See also

- Comparable engines

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Vossler, Bill. "Fageol Trucks Were Their True Claim to Fame". Farm Collector. Ogden Publications. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Trout, Steven (2006). Cather Studies Vol. 6: History, Memory, and War. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 275–276. ISBN 0-8032-9464-6.

- ↑ Yenne, Bill (2006). The American Aircraft Factory in World War II. Zenith Imprint. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-7603-2300-3.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Timothy J. (2002). The Aviation Legacy of Henry & Edsel Ford. Wayne State University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 1-928623-01-8.

- ↑ Anderson, John David (2002). The Airplane: A History of Its Technology. AIAA. p. 157. ISBN 1-56347-525-1.

- ↑ Vincent 1919, p. 400.

- ↑ Weiss 2003, p. 45.

- ↑ Leland and Millbrook 1996, p. 189.

- ↑ Squier, George O. (10 Jan 1919). "Aeronautics In The United States, 1918" (PDF). Transactions Of The American Institute Of Electrical Engineers. XXXVIII: 13. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ Leland and Millbrook 1996, p. 194.

- ↑ Weiss, H. Eugene (2003). Chrysler, Ford, Durant, and Sloan. McFarland. p. 45. ISBN 0-7864-1611-4.

- ↑ Gunston, Bill (1986). World Encyclopaedia of Aero Engines. Patrick Stephens. p. 106. ISBN 0-85059-717-X.

- ↑ http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/AnnalsofFlight/text/SAOF-0001.3.txt

- ↑ Grey, C.G. (1969). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1919 (Facsimile ed.). David & Charles (Publishing) Limited. pp. 1b to 145b. ISBN 0-7153-4647-4.

- ↑ Foreman-Peck, James; Sue Bowden; Alan McKinley (1995). The British Motor Industry. Manchester University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-7190-2612-1.

- ↑ A Technical & Operational History of the Liberty Engine: Tanks, Ships and Aircarf 1917-1960; Robert J. Neal; Speciality Press

- ↑ http://neam.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&layout=edit&id=1076

- ↑ "Cole Palen's Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome - Aircraft Engines - Page 4 - Liberty". oldrhinebeck.org. Rhinebeck Aerodrome Museum. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

Produced in large numbers and used extensively in mail planes following the War, the Liberty was a significant U.S. contribution to aviation. Jesse Vincent of Packard and E.J. Hall of Hall-Scott designed the engine in five days. One month later the first prototype was built and running.

Bibliography

- Bradford, Francis H. Hall-Scott: The Untold Story of a Great American Engine Manufacturer

- Angelucci, Enzo. The Rand McNally Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft, 1914-1980. San Diego, California: The Military Press, 1983. ISBN 0-517-41021-4.

- Barker, Ronald and Anthony Harding. Automotive Design: Twelve Great Designers and Their Work. SAE, 1992. ISBN 1-56091-210-3.

- Leland, Mrs. Wilfred C. and Minnie Dubbs Millbrook. Master of Precision: Henry M. Leland. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8143-2665-X.

- Lewis, David L. 100 Years of Ford. Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications International. 2005. ISBN 0-7853-7988-6.

- "Lincolns." Lincoln Anonymous. Retrieved: August 22, 2006.

- Vincent, J.G. The Liberty Aircraft Engine. Washington, D.C.: Society of Automotive Engineers, 1919.

- Weiss, H. Eugene. Chrysler, Ford, Durant and Sloan: Founding Giants of the American Automotive Industry. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0-7864-1611-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liberty L-12. |

- Schipper, J. Edward (January 2, 1919). "The Liberty Engine" (PDF). Flight. XI (1): 6–10. No. 523. Retrieved January 12, 2011. Contemporary technical description of the engine with drawings and photographs.

- Recovery of a Liberty powered tank

- Annals of Flight

- "V-12, Liberty 12 Model A (Ford) Engine". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome's operable Liberty V-12 engine run video