Amyloidosis

| Amyloidosis | |

|---|---|

|

Classic facial features of AL amyloidosis with purpura around the eyes[1] | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, Rheumatology, Cardiology |

| ICD-10 | E85 |

| ICD-9-CM | 277.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 633 |

| eMedicine | med/3377 |

| Patient UK | Amyloidosis |

| MeSH | D000686 |

Amyloidosis is a rare and serious disease caused by accumulation of proteins in the form of abnormal, insoluble fibres, known as amyloid fibrils, within the extracellular space in the tissues of the body.[2][3] Amyloid deposits can be confined to only one part of the body or a single organ system in 'local amyloidosis' or they can be widely distributed in organs and tissues throughout the body in 'systemic amyloidosis'. The symptoms of amyloidosis are accordingly highly variable and confirmation of the presence of amyloid in the tissues can be challenging, so that diagnosis is often delayed.

Amyloid fibrils are formed by aggregation (clumping) of normally soluble body proteins and accumulate progressively, forming amyloid deposits which disrupt the normal tissue architecture, damaging the function of tissues and organs and causing disease. In contrast to the normally efficient clearance of abnormal debris from the tissues, amyloid deposits are removed very slowly, if at all. There are many different types of amyloidosis, each caused by formation of amyloid fibrils from different soluble precursor proteins in different patients.[3][4] About 30 different proteins are known to form amyloid fibrils in humans[5] and amyloidosis is named and classified according to the identity of the respective fibril protein.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The presentation of amyloidosis is broad and depends on the site of amyloid accumulation. The kidney and heart are the most common organs involved.

Amyloid deposition in the kidneys can cause nephrotic syndrome, which results from a reduction in the kidney's ability to filter and hold on to proteins. The nephrotic syndrome occurs with or without elevations in creatinine and blood urea concentration,[6] two biochemical markers of kidney injury. In AA amyloidosis the kidneys are involved in 91–96% of people,[7] symptoms ranging from protein in the urine to nephrotic syndrome and rarely renal insufficiency.

Amyloid deposition in the heart can cause both diastolic and systolic heart failure. EKG changes may be present, showing low voltage and conduction abnormalities like atrioventricular block or sinus node dysfunction. On echocardiography the heart shows a restrictive filling pattern, with normal to mildly reduced systolic function.[6] AA amyloidosis usually spares the heart.[7]

People with amyloidosis do not get central nervous system involvement but can develop sensory and autonomic neuropathies. Sensory neuropathy develops in a symmetrical pattern and progresses in a distal to proximal manner. Autonomic neuropathy can present as orthostatic hypotension but may manifest more gradually with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms like constipation, nausea, or early satiety.[6]

Accumulation of amyloids in the liver can lead to elevations in serum aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase, two biomarkers of liver injury, which is seen in about one third of people.[7] Liver enlargement is common. In contrast, spleen enlargement is rare, occurring in 5% of people. Splenic dysfunction, leading to the presence of Howell-Jolly bodies on blood smear, occurs in 24% of people with amyloidosis.[6] Malabsorption is seen in 8.5% of AL amyloidosis and 2.4% of AA amyloidosis. One suggested mechanism for the observed malabsorption is that amyloid deposits in the tips of intestinal villi (fingerlike projections that increase the intestinal area available for absorption of food), begin to erode the functionality of the villi, presenting a sprue-like picture.[7]

A rare development is a susceptibility to bleeding with bruising around the eyes, termed "racoon-eyes". This is caused by amyloid deposition in the blood vessels and a reduced activity of thrombin and factor X, two clotting proteins that lose their function after binding with amyloid.[6]

Amyloid deposits in tissue and causes enlargement of structures. Twenty percent of people with AL amyloidosis have an enlarged tongue, that can lead to obstructive sleep apnea, difficulty swallowing, and altered taste.[7] Tongue enlargement does not occur in ATTR or AA amyloidosis.[6] Enlarged shoulders, "shoulder pad sign", results from amyloid deposition in synovial space. Deposition of amyloid in the throat can cause hoarseness.[6] Aβ2MG amyloidosis (Hemodialysis associated amyloidosis) likes to deposit in synovial tissue causing chronic synovitis which can lead to repeated carpal tunnel syndrome.[7]

Both the thyroid and adrenal gland can be infiltrated. It is estimated that 10–20% of individuals with amyloidosis have hypothyroidism. Adrenal infiltration may be harder to appreciate given that its symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and low blood sodium concentration may be attributed to autonomic neuropathy and heart failure.[6]

"Amyloid deposits occur in the pancreas of patients with diabetes mellitus, although it is not known if this is functionally important. The major component of pancreatic amyloid is a 37-amino acid residue peptide known as islet amyloid polypeptide or amylin. This is stored with insulin in secretory granules in B cells and is co secreted with insulin". (Rang and Dale's Pharmacology, 2015).

Pathogenesis

The cells in the body have two different ways of making proteins. Some proteins are made of one single piece or sequence of aminoacids; in other cases protein fragments are produced, and the fragments come and join together to form the whole protein. But such a protein can sometimes fall apart into the original protein fragments. This process of "flip flopping" happens frequently for certain protein types, especially the ones that cause amyloidosis.

The fragments or actual proteins are at risk of misfolding as they are synthesized, to make a poorly functioning protein. This causes proteolysis, which is the directed breakdown of proteins by cellular enzymes called proteases or by intramolecular digestion; proteases come and digest the misfolded fragments and proteins. The problem occurs when the proteins do not dissolve in proteolysis. This happens because the misfolded proteins sometimes become robust enough that they are not dissolved by normal proteolysis. When the fragments do not dissolve, they get spit out of proteolysis and they aggregate to form oligomers. The reason they aggregate is that the parts of the protein that do not dissolve in proteolysis are the β-pleated sheets, which are extremely hydrophobic. They are usually sequestered in the middle of the protein, while parts of the protein that are more soluble are found near the outside. When they are exposed to water, these hydrophobic pieces tend to aggregate with other hydrophobic pieces. This ball of fragments gets stabilized by GAGs (glycosaminoglycans) and SAP (serum amyloid P), a component found in amyloid aggregations that is thought to stabilize them and prevent proteolytic cleavage. The stabilized balls of protein fragments are called oligomers. The oligomers can aggregate together and further stabilize to make amyloid fibrils.

Both the oligomers and amyloid fibrils are toxic to cells and can interfere with proper organ function.[8]

Diagnosis

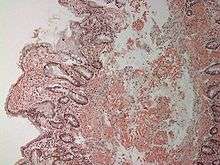

Diagnosis of amyloidosis requires tissue biopsy. Biopsy is assessed for evidence of characteristic amyloid deposits. The tissue is treated with various stains. The most useful stain in the diagnosis of amyloid is Congo red, which, combined with polarized light, makes the amyloid proteins appear apple-green on microscopy. Also, thioflavin T stain may be used.[9]

Tissue can come from any involved organ. But in systemic disease first line site of biopsy is subcutaneous abdominal fat, known as a fat pad biopsy, because it's simple to acquire and less invasive than biopsy of the rectum, salivary gland or internal organs. An abdominal fat biopsy is not completely sensitive and so, sometimes, biopsy of an involved organ (such as the kidney) is required to achieve a diagnosis.[9] For example, in AL amyloidosis only 85% of people will have a positive fatpad biopsy using Congo red stain.[6] By comparison, rectal biopsy has sensitivity of 74–94%.[7]

The type of the amyloid protein can be determined by various ways: the detection of abnormal proteins in the bloodstream (on protein electrophoresis or light chain determination), binding of particular antibodies to the amyloid found in the tissue (immunohistochemistry), or extraction of the protein and identification of its individual amino acids.[9] Immunohistochemistry can identify AA amyloidosis the majority of the time, but can miss many cases of AL amyloidosis.[7] Laser microdissection with mass spectrometry is the most reliable method of identifying the different forms of amyloidosis.[10]

Since AL is the most common variation, diagnoses often begins with a search for plasma cell dyscrasias, memory B cells producing aberrant immunoglobulins or portions of immunoglobulins. Immunofixation electrophoresis of urine or serum is positive in 90% of people with AL amyloidosis.[6] Immunofixation electrophoresis is more sensitive than regular electrophoresis but may not be available in all centers. Alternatively immunohistochemical staining of a bone marrow biopsy looking for dominant plasma cell can be sought in people with a high clinical suspicion for AL amyloidosis but negative electrophoresis.[6]

ATTR is suspected in people with family history of idiopathic neuropathies or heart failure who lack evidence of plasma cell dyscrasias. ATTR can be identified using isoelectric focusing which separates out mutated forms of transthyretin. Findings can be corroborated by genetic testing to look for specific known mutations in transthyretin that predispose to amyloidosis.[6]

AA is suspected on clinical grounds in individuals with longstanding infections or inflammatory diseases. AA can be identified by immunohistochemistry staining.[6]

-

Small bowel duodenum with amyloid deposition Congo red 10X

-

Amyloidosis, dystrophic calcification

-

Small bowel duodenum with amyloid deposition 20X

-

Amyloidosis, Node, Congo Red

-

Amyloidosis, blood vessels, H&E

-

Amyloidosis, lymph node, H&E

-

Amyloidosis, lymph node, polarizer

-

Micrograph showing amyloid deposition (red fluffy material) in the heart (cardiac amyloidosis). Congo red stain.

Classification

Historical classification systems were based on clinical factors. Until the early 1970s, the idea of a single amyloid substance predominated. Various descriptive classification systems were proposed based on the organ distribution of amyloid deposits and clinical findings. Most classification systems included primary (i.e., idiopathic) amyloidosis, in which no associated clinical condition was identified, and secondary amyloidosis (i.e., secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions). Some classification systems included myeloma-associated, familial, and localized amyloidosis.

The modern era of amyloidosis classification began in the late 1960s with the development of methods to make amyloid fibrils soluble. These methods permitted scientists to study the chemical properties of amyloids. Descriptive terms such as primary amyloidosis, secondary amyloidosis, and others (e.g., senile amyloidosis), which are not based on etiology, provide little useful information and are no longer recommended.

The modern classification of amyloid disease tends to use an abbreviation of the protein that makes the majority of deposits, prefixed with the letter A. For example, amyloidosis caused by transthyretin is termed "ATTR". Deposition patterns vary between people but are almost always composed of just one amyloidogenic protein. Deposition can be systemic (affecting many different organ systems) or organ-specific. Many amyloidoses are inherited, due to mutations in the precursor protein.

Other forms are due to different diseases causing overabundant or abnormal protein production – such as with overproduction of immunoglobulin light chains (termed AL amyloidosis), or with continuous overproduction of acute phase proteins in chronic inflammation (which can lead to AA amyloidosis).

About 60 amyloid proteins that have been identified so far,.[11] Of those, at least 36 have been associated with a human disease.[12]

The names of amyloids usually start with the letter "A". Here is a brief description of the more common types of amyloid:

| Official abb. |

Amyloid type/Gene | Description | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|

| AL | amyloid light chain | AL amyloidosis / multiple myeloma. Contains immunoglobulin light-chains (λ,κ) derived from plasma cells. | 254500 |

| AA | SAA | Serum amyloid A protein (SAA) is an acute-phase reactant that is produced in times of inflammation. | |

| Aβ | β amyloid/APP | Found in Alzheimer disease brain lesions. | 605714 |

| ALect2 | LECT2 | In LECT2 amyloidosis, the LECT2 protein will deposit in the kidneys, resulting in symptoms typical of kidney failure. | 602882 |

| ATTR | transthyretin | Transthyretin is a protein that is mainly formed in the liver that transports thyroxine and retinol binding protein.[6] A mutant form of a normal serum protein that is deposited in the genetically determined familial amyloid polyneuropathies. TTR is also deposited in the heart in Wild type transthyretin amyloidosis otherwise known as senile systemic amyloidosis.[13] Also found in leptomeningeal amyloidosis. | 105210 |

| Aβ2M | β2 microglobulin | Not to be confused with Aβ, β2m is a normal serum protein, part of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class 1 molecules. Haemodialysis-associated amyloidosis | |

| AIAPP | amylin | Found in the pancreas of people with type 2 diabetes. | |

| APrP | prion protein | In prion diseases, misfolded prion proteins deposit in tissues and resemble amyloid proteins. Some examples are Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (humans), BSE or "mad cow disease" (cattle), and scrapie (sheep and goats). A recently described familial prion disease presents with peripheral amyloidosis causing autonomic neuropathy and diarrhea.[14] | 123400 |

| AGel | GSN | Finnish type amyloidosis | 105120 |

| ACys | CST3 | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Icelandic-type | 105150 |

| AApoA1 | APOA1 | Familial visceral amyloidosis | 105200 |

| AFib | FGA | Familial visceral amyloidosis | 105200 |

| ALys | LYZ | Familial visceral amyloidosis | 105200 |

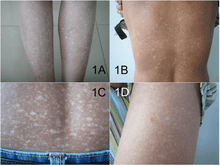

| ? | OSMR | Primary cutaneous amyloidosis | 105250 |

| ABri ADan |

ITM2B | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, British-type Danish-type |

176500 117300 |

| APro | prolactin | Prolactinoma | |

| AKer | keratoepithelin | Familial corneal amyloidosis | |

| AANF | atrial natriuretic factor | Senile amyloid of atria of heart | |

| ACal | calcitonin | Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid |

As of 2010, 27 human and 9 animal fibril proteins were classified, along with 8 inclusion bodies.[15]

Alternative

An older clinical method of classification refers to amyloidoses as systemic or localised

- Systemic amyloidoses affect more than one body organ or system. Examples are AL, AA and Aβ2m.[16]

- Localised amyloidoses affect only one body organ or tissue type. Examples are Aβ, IAPP, Atrial natriuretic factor (in isolated atrial amyloidosis), and Calcitonin (in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid)[16]

Another classification is primary or secondary.

- Primary amyloidoses arise from a disease with disordered immune cell function, such as multiple myeloma or other immunocyte dyscrasias.

- Secondary (reactive) amyloidoses occur as a complication of some other chronic inflammatory or tissue-destroying disease. Examples are reactive systemic amyloidosis and secondary cutaneous amyloidosis.[16]

Additionally, based on the tissues in which it is deposited, it is divided into mesenchymal (organs derived from mesoderm) or parenchymal (organs derived from ectoderm or endoderm).

Treatment

Treatment depends on the type of amyloidosis that is present. Treatment with high dose melphalan, a chemotherapy agent, followed by stem cell transplantation has showed promise in early studies and is recommended for stage I and II AL amyloidosis.[10] However, only 20–25% of people are eligible for stem cell transplant. Chemotherapy and steroids, with melphalan plus dexamethasone, is mainstay treatment in AL people not eligible for transplant.[10]

In AA, symptoms may improve if the underlying condition is treated; eprodisate has been shown to slow renal impairment by inhibiting polymerization of amyloid fibrils.

In ATTR, liver transplant is curative therapy[6] because mutated transthyretin which forms amyloids is produced in the liver.

People affected by amyloidosis are supported by multiple organizations, including the Amyloidosis Foundation, Amyloidosis Support Groups Inc., and Amyloidosis Australia, Inc.[17][18]

Prognosis

Prognosis varies with the type of amyloidosis. Prognosis for untreated AL amyloidosis is poor with median survival of one to two years. More specifically, AL amyloidosis can be classified as stage I, II or III based on cardiac biomarkers like troponin and BNP. Survival diminishes with increasing stage, with estimated survival of 26, 11 and 3.5 months at stage I, II and III.[10]

Outcomes in a person with AA amyloidosis depends on the underlying disease and correlates with the concentration of serum amyloid A protein.[7]

People with ATTR have better prognosis and may survive for over a decade.[6]

Senile systemic amyloidosis was determined to be the primary cause of death for 70% of people over 110 who have been autopsied.[19][20]

Epidemiology

The three most common forms of amyloidosis are AL, AA and ATTR amyloidoses. The median age at diagnosis is 64.[7]

In the western hemisphere, AL is the most prevalent, comprising 90% of cases.[10] In the United States it's estimated that there are 1275 to 3200 new cases of AL amyloidoses every year.[6]

AA amyloidoses is the most common form in developing countries and can complicate longstanding infections with tuberculosis, osteomyleitis and bronchiectesis. In the west, AA is more likely to occur from autoimmune inflammatory states.[6] Most common etiologies of AA amylodosis in the west are rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis and familial Mediterranean fever.

People undergoing long term hemodialysis (14–15 years) can develop amyloidosis from accumulation of light chains of the HLA 1 complex which is normally filtered out by the kidneys.[7]

Senile amyloidosis resulting from deposition of normal transthyretin, mainly in the heart, is found in 10–36% of people over 80.[7]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Hawkins, P (29 Apr 2015). "AL amyloidosis". Wikilite.com. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Wechalekar, Ashutosh D.; Gillmore, Julian D.; Hawkins, Philip N. (2015-12-21). "Systemic amyloidosis". Lancet (London, England). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01274-X. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 26719234.

- 1 2 Pepys, Mark B. (2006-01-01). "Amyloidosis". Annual Review of Medicine. 57: 223–41. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243. ISSN 0066-4219. PMID 16409147.

- 1 2 Pepys MB and Hawkins PN, Amyloidosis. (2012). "Oxford Textbook of Medicine" (5th ed.). Edited by Warrel DA, Cox TM, Firth JD. doi:10.1093/med/9780199204854.001.1/med-9780199204854.

- ↑ Sipe, Jean D.; Benson, Merrill D.; Buxbaum, Joel N.; Ikeda, Shu-ichi; Merlini, Giampaolo; Saraiva, Maria J. M.; Westermark, Per (2014-12-01). "Nomenclature 2014: Amyloid fibril proteins and clinical classification of the amyloidosis". Amyloid. 21 (4): 221–24. doi:10.3109/13506129.2014.964858. ISSN 1744-2818. PMID 25263598.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Falk, Rodney H.; Comenzo, Raymond L.; Skinner, Martha (25 September 1997). "The Systemic Amyloidoses". New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (13): 898–909. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709253371306.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ebert, Ellen C.; Nagar, Michael (March 2008). "Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Amyloidosis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (3): 776–87. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01669.x.

- ↑ , Karp, Judith E., ed. Amyloidosis Diagnosis and Treatment. Rochester: Humana, 2010. Online Source.

- 1 2 3 Dember LM (December 2006). "Amyloidosis-associated kidney disease". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17 (12): 3458–71. doi:10.1681/ASN.2006050460. PMID 17093068.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosenzweig, Michael; Landau, Heather (2011). "Light chain (AL) amyloidosis: update on diagnosis and management". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 4 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-4-47.

- ↑ Mok KH, Pettersson J, Orrenius S, Svanborg C (March 2007). "HAMLET, protein folding, and tumor cell death". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.167. PMID 17223074.

- ↑ Pettersson-Kastberg J, Aits S, Gustafsson L, et al. (November 2008). "Can misfolded proteins be beneficial? The HAMLET case". Ann. Med. 41 (3): 1–15. doi:10.1080/07853890802502614. PMID 18985467.

- ↑ Hassan W, Al-Sergani H, Mourad W, Tabbaa R (2005). "Amyloid heart disease. New frontiers and insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management". Tex Heart Inst J. 32 (2): 178–84. PMC 1163465

. PMID 16107109.

. PMID 16107109. - ↑ Mead et al. A Novel Prion Disease Associated with Diarrhea and Autonomic Neuropathy. N Engl J Med 369:1904–14, 2013.

- ↑ Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, et al. (September 2010). "Amyloid fibril protein nomenclature: 2010 recommendations from the nomenclature committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis". Amyloid. 17 (3–4): 101–04. doi:10.3109/13506129.2010.526812. PMID 21039326.

- 1 2 3 Table 5-12 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ "Amyloidosis - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ↑ "Amyloidosis primary cutaneous – Disease – Organizations – Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ↑ Coles LS, Young RD (2012). "Supercentenarians and transthyretin amyloidosis: the next frontier of human life extension". PREVENTATIVE MEDICINE. 54 (Suppl): s9–s11. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.003. PMID 22579241.

- ↑ "Searching for the Secrets of the Super Old". Science. September 26, 2008. pp. 1764–65. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

External links

- Amyloidosis at DMOZ

- National Press Club Luncheon with Michael York, August 2016. Michael York who has amyloidosis, speaks from 4:00-60:00