Anionic addition polymerization

Ionic polymerization in which the active centers are anions.

Note 1: The anions may be free, paired, or aggregated.

Penczek S.; Moad, G. Pure Appl. Chem., 2008, 80(10), 2163-2193

Anionic addition polymerization is a form of chain-growth polymerization or addition polymerization that involves the polymerization of vinyl monomers with strong electronegative groups.[3][4] This polymerization is carried out through a carbanion active species.[5] Like all chain-growth polymerizations, it takes place in three steps: chain initiation, chain propagation, and chain termination. Living polymerizations, which lack a formal termination pathway, occur in many anionic addition polymerizations. The advantage of living anionic addition polymerizations is that they allow for the control of structure and composition.[3][4]

Anionic polymerizations are used in the production of polydiene synthetic rubbers, solution styrene/butadiene rubbers (SBR), and styrenic thermoplastic elastomers.[3]

History

As early as 1936, Karl Ziegler proposed that anionic polymerization of styrene and butadiene by consecutive addition of monomer to an alkyl lithium initiator occurred without chain transfer or termination. Twenty years later, living polymerization was demonstrated by Szwarc. The early work of Michael Szwarc and co – workers in 1956 was one of the breakthrough events in the field of polymer science. When Szwarc learned that the electron transfer between radical anion of naphthalene and styrene in an aprotic solvent such as tetrahydrofuran gave a messy product, he started investigating the reaction in more detail. He proved that the electron transfer results in the formation of a dianion which rapidly added styrene to form a "two – ended living polymer." Being a physical chemist, Szwarc set forth in understanding the mechanism of such living polymerization in greater detail. His work elucidated the kinetics and the thermodynamics of the process in considerable detail. At the same time, he explored the structure property relationship of the various ion pairs and radical ions involved. This had great ramifications in future research in polymer synthesis, because Szwarc had found a way to make polymers with greater control over molecular weight, molecular weight distribution and the architecture of the polymer.[6]

The use of alkali metals to initiate polymerization of 1,3-dienes led to the discovery by Stavely and co-workers at Firestone Tire and Rubber company of cis-1,4-polyisoprene.[7] This sparked the development of commercial anionic polymerization processes that utilize alkyllithium initiatiors.[4]

Monomer Characteristics

In order for polymerization to occur with vinyl monomers, the substituents on the double bond must be able to stabilize a negative charge. Stabilization occurs through delocalization of the negative charge. Because of the nature of the carbanion propagating center, substituents that react with bases or nucleophiles either must not be present or be protected.[4]

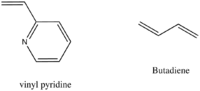

Vinyl monomers with substituents that stabilize the negative charge through charge delocalization, undergo polymerization without termination or chain transfer.[4] These monomers include styrene, dienes, methacrylate, vinyl pyridine, aldehydes, epoxide, episulfide, cyclic siloxane, and lactones.

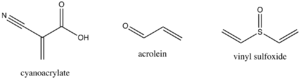

Polar monomers, using controlled conditions and low temperatures, can undergo anionic polymerization. However, at higher temperatures they do not produce living stable, carbanionic chain ends because their polar substituents can undergo side reactions with both initiators and propagating chain centers. The effects of counterion, solvent, temperature, Lewis base additives, and inorganic solvents have been investigated to increase the potential of anionic polymerizations of polar monomers.[4] Polar monomers include acrylonitrile, cyanoacrylate, propylene oxide, vinyl ketone, acrolein, vinyl sulfone, vinyl sulfoxide, vinyl silane and isocyanate.

Solvent

The solvent used in anionic addition polymerizations are determined by the reactivity of both the initiator and carbanion of the propagating chain end. Anionic species with low reactivity, such as heterocyclic monomers, can use a wide range of solvents.[4]

Initiation

The reactivity of initiators used in anionic polymerization should be similar to that of the monomer that is the propagating species. The pKa values for the conjugate acids of the carbanions formed from monomers can be used to deduce the reactivity of the monomer. The least reactive monomers have the largest pKa values for their corresponding conjugate acid and thus, require the most reactive initiator. Two main initiation pathways involve electron transfer (through alkali metals) and strong anions.[4]

Initiation by Electron Transfer

Szwarc and coworkers studied the initiation of polymerization through the use of aromatic radical-anions such as sodium naphthenate.[7] In this reaction, an electron is transferred from the alkali metal to naphthalene. Polar solvents are necessary for this type of initiation both for stability of the anion-radical and to solvate the cation species formed.[7] The anion-radical can then transfer an electron to the monomer.

Initiation can also involve the transfer of an electron from the alkali metal to the monomer to form an anion-radical. Initiation occurs on the surface of the metal, with the reversible transfer of an electron to the adsorbed monomer.[4]

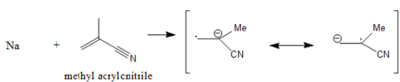

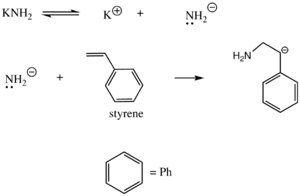

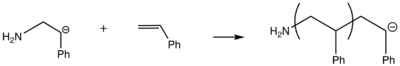

Initiation by Strong Anions

Nucleophilic initiators include covalent or ionic metal amides, alkoxides, hydroxides, cyanides, phosphines, amines and organometallic compounds (alkyllithium compounds and Grignard reagents). The initiation process involves the addition of a neutral (B:) or negative (B:-) nucleophile to the monomer.[7]

The most commercially useful of these initiators has been the alkyllithium initiators. They are primarily used for the polymerization of styrenes and dienes.[4]

Monomers activated by strong electronegative groups may be initiated even by weak anionic or neutral nucleophiles (i.e. amines, phosphines). Most prominent example is the curing of cyanoacrylate, which constitutes the basis for superglue. Here, only traces of basic impurities are sufficient to induce an anionic addition polymerization or zwitterionic addition polymerization, respectively.[8]

Propagation

Propagation in anionic addition polymerization results in the complete consumption of monomer. It is very fast and occurs at low temperatures. This is due to the anion not being very stable, the speed of the reaction as well as that heat is released during the reaction. The stability can be greatly enhanced by reducing the temperatures to near 0˚C. The propagation rates are generally fairly high compared to the decay reaction, so the overall polymerization rates is generally not affected.[3]

Termination

Anionic addition polymerizations have no formal termination pathways because proton transfer from solvent or other positive species does not occur. However, termination can occur through unintentional quenching due to trace impurities. This includes trace amounts of oxygen, carbon dioxide or water. Intentional termination can occur through the addition of water or alcohol. Another method of termination, chain transfer, can occur when an agent can act as a Brønsted acid.[7] In this case, the pKa value of the agent is similar to the conjugate acid of the propagating carbanionic chain end. Spontaneous termination occurs because the concentration of carbanion centers decay over time and eventually results in hydride elimination. Polar monomers are more reactive because they are stabilized by their polar substituents. These polar substituents can react with nucleophiles which results in termination as well as side reactions that compete with both initiation and propagation.[7]

Living Anionic Polymerization

Living polymerization was demonstrated by Szwarc and co workers in 1956. Their initial work was based on the polymerization of styrene and dienes. One of the remarkable features of living anionic polymerization is that the mechanism involves no formal termination step. In the absence of impurities, the carbanion would still be active and capable of adding another monomer. The chains will remain active indefinitely unless there is inadvertent or deliberate termination or chain transfer.

Kinetics

The kinetics of anionic addition polymerization depend on whether or not a termination pathway occurs.[3][7]

Kinetics of Living Anionic Addition Polymerization

In general, the reaction mechanism for living anionic addition polymerization are as follows:

where I = initiator, kinit = the initiation reaction rate constant, M = monomer, M−= propagating species, and kprop = the propagation reaction rate constant.

As most polymerizations of this type do not have a termination pathway, the rate of polymerization is the rate of propagation:

where kp is the rate of constant of propagation, [M−] is the total concentration of propagating centers, and [M] is the concentration of monomer. Since there is no termination pathway in living polymerizations, the concentration of propagating centers is equal to the concentration of initiator ([I]). Thus,

The degree of polymerization, Xn is also affected by no termination pathway. It is the ratio of concentration of reacted monomer ([M]o) to initiator([I]o) times the percent conversion p. In this case, the chain length (ν) is equal to Xn.

When conversion, p = 1 (100% conversion), chain length is simply the ratio of reacted monomer to initiator.

Kinetics: Termination due to Impurities

When termination occurs due to impurities, the impurities must be taken into account in determining the reaction rate. The reaction mechanisms would begin the same as that of a living anionic addition (initiation and propagation). However, there would now be a termination step to account for the effect of the impurities on the reaction.

where M−= propagating species, HX = impurity and kterm = the termination reaction rate constant.

Using the steady-state approximation, the rate of propagation becomes

Since

Thus chain length and rate of propagation are negatively impacted by the presence of impurities in the reaction.

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Anionic polymerization".

- ↑ Jenkins, A. D.; Kratochvíl, P.; Stepto, R. F. T.; Suter, U. W. (1996). "Glossary of basic terms in polymer science (IUPAC Recommendations 1996)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 68 (12): 2287–2311. doi:10.1351/pac199668122287.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hsieh, H.;Quirk, R. Anionic Polymerization: Principles and practical applications; Marcel Dekker, Inc: New York, 1996.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Quirk, R. Anionic Polymerization. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 2003.

- ↑ Blackeley, D.; Twaits, R. Ionic Polymerization. In Addition Polymers: Formation and Characterization; Plenum Press: New York, 1968; pp. 51-110.

- ↑ Smid, J. Historical Perspectives on Living Anionic Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A.; 2002, 40,pp. 2101-2107. DOI=10.1002/pola.10286

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Odian, G. Ionic Chain Polymerization; In Principles of Polymerization; Wiley-Interscience: Staten Island, New York, 2004, pp. 372-463.

- ↑ Pepper, D.C. Zwitterionic Chain Polymerizations of Cyanoacrylates. Macromolecular Symposia; 1992,60,pp. 267-277.