The Bad and the Beautiful

| The Bad and the Beautiful | |

|---|---|

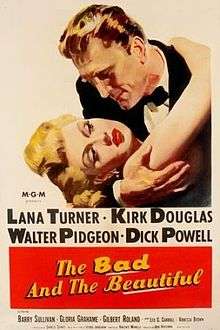

Promotional poster for the film | |

| Directed by | Vincente Minnelli |

| Produced by | John Houseman |

| Screenplay by | Charles Schnee |

| Based on | "Tribute to a Badman" by George Bradshaw |

| Starring |

Lana Turner Kirk Douglas Walter Pidgeon Dick Powell Barry Sullivan Gloria Grahame Gilbert Roland |

| Music by | David Raksin |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees |

| Edited by | Conrad A. Nervig |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1952, original) Warner Bros. (2002, DVD Warner Classics) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1,558,000[1] |

| Box office | $3,373,000[1] |

The Bad and the Beautiful is a 1952 MGM melodrama that tells the story of a film producer who alienates all around him. It stars Lana Turner, Kirk Douglas, Walter Pidgeon, Dick Powell, Barry Sullivan, Gloria Grahame and Gilbert Roland. The film was directed by Vincente Minnelli and written by George Bradshaw and Charles Schnee.

The Bad and the Beautiful resulted in five Academy Awards out of six nominations in 1952, a record for the most awards for a movie that was not nominated for Best Picture nor for Best Director.

In 2002, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. The theme song, "The Bad and the Beautiful", penned by David Raksin, became a jazz standard and has been cited as an example of an excellent movie theme.

The Bad and the Beautiful was created by the same team that later worked on another film about the movie business, Two Weeks in Another Town (1962): director (Vincente Minnelli), producer (John Houseman), screenwriter (Charles Schnee), composer (David Raksin), male star (Kirk Douglas), and studio (MGM). Both movies also feature performances of the song "Don't Blame Me," by Leslie Uggams in Two Weeks and by Peggy King in The Bad and the Beautiful. In one scene of Two Weeks in Another Town, the cast watches clips from The Bad and the Beautiful in a screening room, presented as a movie that Douglas's character in Two Weeks, Jack Andrus, had starred in. Two Weeks is not a sequel however, as the characters in the two stories are unrelated.

Plot

In Hollywood, director Fred Amiel (Barry Sullivan), movie star Georgia Lorrison (Lana Turner), and screenwriter James Lee Bartlow (Dick Powell) each refuse to speak by phone to Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) in Paris. Movie producer Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon) gathers them in his office and explains that Shields was calling them because he has a new film idea and he wants the three of them for the project. Shields cannot get financing on his own, but with their names attached, there would be no problem. Pebbel asks the three to allow him to get Shields on the phone before they give their final answer.

As they await Shields' call, Pebbel assures the three that he understands why they refused to speak to Shields. The backstory of their involvement with Shields then unfolds in a series of flashbacks. Shields is the son of a notorious former studio head who had been dumped by the industry. The elder Shields was so unpopular that his son had to hire "extras" to attend his funeral. Despite the industry's ill feelings toward him because of his father, the younger Shields is determined to make it in Hollywood by any means necessary.

Shields partners with aspiring director Amiel, whom he meets at his father's funeral. Shields intentionally loses money he does not have in a poker game to film executive Pebbel, so he can talk Pebbel into letting him work off the debt as a line producer. Shields and Amiel learn their respective trades making B movies for Pebbel. When one of their films becomes a hit, Amiel decides they are ready to take on a more significant project he has been nursing along, and Shields pitches it to the studio. Shields gets a $1 million budget to produce the film, but betrays Amiel by allowing someone with an established reputation to be chosen as director. The film's success allows Shields to start his own studio, and Pebbel comes to work for him there. Amiel, now independent of Shields, goes on to become an Oscar-winning director in his own right.

Shields next encounters alcoholic small-time actress Lorrison, the daughter of a famous actor Shields admired. He builds up her confidence and gives her the leading role in one of his movies over everyone else's objections. When she falls in love with him, he lets her think that he feels the same way so that she does not self-destruct and he gets the performance he needs. After a smash premiere makes her a star overnight, she finds him with a beautiful bit player named Lila (Elaine Stewart). He drives Lorrison away, telling her that he will never allow anyone to have that much control over him. Crushed over being jilted by Shields, Lorrison walks out on her contract with his studio. Rather than take her to court, Shields releases his rights to her, freeing her to go to another studio, which makes a fortune from her films as she becomes a top Hollywood star.

Finally, Bartlow is a contented professor at a small college who has written a bestselling book for which Shields has purchased the film adaptation rights. Shields wants Bartlow himself to write the film's script. Bartlow is not interested, but his shallow Southern belle wife, Rosemary (Gloria Grahame) is, so he agrees to do it for her sake. They go to Hollywood, where Shields is annoyed to find that her constant distractions are keeping her husband from his work. He gets his suave actor friend Victor "Gaucho" Ribera (Gilbert Roland) to keep her occupied. Freed from interruption, Bartlow is able to make excellent progress on the script. Rosemary, however, runs off with Gaucho and they are killed in a plane crash. When the script is completed, Shields has the distraught Bartlow remain in Hollywood to help with the production as Shields takes over directing duties himself. A first-time director, Shields botches the job, which leads to his bankruptcy. Then Shields lets slip a casual remark that reveals his complicity in Rosemary's affair with Gaucho, so Bartlow walks out on him. Now able to view his late wife more objectively, Bartlow goes on to write a novel based upon her (something Shields had previously encouraged him to do) and wins a Pulitzer Prize for it.

After each flashback, Pebbel sarcastically agrees that Shields "ruined" their lives, making his true point that each of the three, despite feeling betrayed, is now at the top of the movie business, thanks largely to Shields. At last, Shields' telephone call comes through and Pebbel asks the three if they will work with Shields just one more time; all three reject the plea. As they leave the room, Pebbel is still talking to Shields. Out of Pebbel's sight, the three eavesdrop using an extension phone while Shields describes his new idea, and they become more and more interested.

Cast

- Lana Turner as Georgia Lorrison

- Kirk Douglas as Jonathan Shields

- Dick Powell as James Lee Bartlow

- Walter Pidgeon as Harry Pebbel

- Barry Sullivan as Fred Amiel

- Gloria Grahame as Rosemary Bartlow

- Gilbert Roland as Victor "Gaucho" Ribera

- Paul Stewart as Syd

- Ivan Triesault as Von Ellstein

- Leo G. Carroll as Henry Whitfield

- Sammy White as Gus

- Elaine Stewart as Lila

Production

The film was based on a 1949 magazine story Of Good and Evil by George Bradshaw, which was expanded into a longer version called Memorial to a Bad Man. It concerned the will and testament of a New York theatre producer who tried to explain his bad behavior to three people he had hurt, a writer, actor and director. MGM bought the film rights and originally Dan Hartman was to produce it. Hartman left for Paramount.[2]

The project was assigned to John Houseman and was to be called Memo to a Bad Man. Houseman decided to change the milieu from New York theatre to Hollywood because he felt after All About Eve that a Hollywood setting would have more novelty.[3] Clark Gable was originally attached to star; then Spencer Tracy.[4] Eventually Kirk Douglas signed to play the lead. Vincent Minelli was to direct.

"People who read the script asked me why I wanted to do it," said Vincente Minelli. "It was against Hollywood, etc. I told them I didn't see the man as an unregenerate heel - first because we find out he has a weakness, which makes him human, and second, because he's tough on himself as he is on everyone else, which makes him honest. That's the complex,wonderful thing about human beings - whether they're in Hollywood, in the automobile business, or in neckties."[5]

Relation to real-life personalities

There has been much debate as to which real-life Hollywood legends are represented by the film's characters. At the time of the film's release, stories about its basis caused David O. Selznick — whose real life paralleled in some respects that of the "father-obsessed independent producer" Jonathan Shields — to have his lawyer view the film and determine whether it contained any libelous material.[6] Shields is thought to be a blending of Selznick, Orson Welles and Val Lewton.[7] Dore Schary, head of MGM at the time, said Shields was a combination of "David O. Selznick and as yet unknown David Merrick."[8]

Lewton's Cat People is clearly the inspiration behind the early Shields-Amiel film Doom of the Cat Men.[9]

The Georgia Lorrison character is the daughter of a "Great Profile" actor like John Barrymore (Diana Barrymore's career was in fact launched the same year as her father's death), but it can also be argued that Lorrison includes elements of Minnelli's ex-wife Judy Garland.[10] Gilbert Roland's Gaucho may almost be seen as self-parody, as he had recently starred in a series of Cisco Kid pictures, though the character's name, Ribera, would seem to give a nod also to famed Hollywood seducer Porfirio Rubirosa. The director Henry Whitfield (Leo G. Carroll) is a "difficult" director modeled on Alfred Hitchcock, and his assistant Miss March (Kathleen Freeman) is modeled on Hitchcock's wife Alma Reville. The James Lee Bartlow character may have been inspired by Paul Eliot Green, the University of North Carolina academic-turned-screenwriter of The Cabin in the Cotton.

Reception

According to MGM records, the film earned $2,367,000 in the US and Canada and $1,006,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $484,000.[1]

Academy Awards

- Awards[11]

- Best Supporting Actress: Gloria Grahame. Her screen time of just over 9 minutes was at the time the shortest performance to ever win an Academy Award for acting, a record she held until 1977 when Beatrice Straight set a new record (of five minutes and forty seconds).[12]

- Best Art Direction (Black-and-White): Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons, Edward Carfagno; Set Decoration: Edwin B. Willis, Keogh Gleason

- Best Cinematography (Black-and-White): Robert Surtees

- Best Costume Design (Black-and-White): Helen Rose

- Best Writing, Adapted Screenplay: Charles Schnee

- Nominations

- Best Actor: Kirk Douglas

Theme song

David Raksin wrote the theme song "The Bad and the Beautiful" (originally called "Love is For the Very Young") for the film. Upon first hearing the song, Minnelli and Houseman nearly rejected it, but were convinced to keep it by Adolph Green and Betty Comden.[13] After the film's release, the song became a hit[14] and a jazz standard,[15] and has been widely covered.[16]

A number of film music experts and composers, including Stephen Sondheim, have highly praised the theme.[13][16] In a Chicago Tribune article about the theme entitled "Anatomy of a Great Movie Theme", critic Michael Phillips wrote, "Its hypnotic way of combining dissonance with resolutions that never quite resolve when, or how, you expect them to, keeps a listener perpetually intrigued. The bittersweet quality proves elusive and addictive. It's perfect for the Douglas character, and for what Minnelli called the Hollywood-insider script's alternately 'affectionate and cynical' air."[16]

DVD

The Bad and the Beautiful was released to DVD by Warner Home Video on February 5, 2002 as a Region 1 fullscreen DVD.

References

- 1 2 3 The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ↑ Brady, Thomas F. (23 Apr 1951). "AVA GARDNER GETS ROLE WITH GABLE: Named for Metro's 'Lone Star,' Story of Texas Annexation Hartman Project Revived". New York Times. p. 21.

- ↑ Schallert, Edwin (20 Apr 1951). "Drama: Hal Wallis Signs 'Sheba' Star; Houseman Readies Two Stories for Screen". Los Angeles Times. p. B7.

- ↑ MOVIELAND BRIEFS Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 01 Oct 1951: B10.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (30 Nov 1952). "Minnelli Film Work Reveals Him as Poet: Director Unassuming, However; Just Tells Them How He Wants It Done". Los Angeles Times. p. E3.

- ↑ Miller, Frank (2016). "Behind the Camera on The Bad and the Beautiful". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ Tim Dirks. "The Bad And The Beautiful (1952)". filmsite.org.

- ↑ Schary, Dore (1979). Heyday. p. 246.

- ↑ Glenn Erickson (February 28, 2002). "The Bad and the Beautiful". DVD Savant. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ↑ Karina Longworth (August 15, 2007). "Star-making as Fetish: The Bad and the Beautiful". blog.spout.com.

- ↑ "Oscars.org -- The Bad and the Beautiful". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ Cloete, Kervyn (2015-01-29). "Top List Thursday – Oscar winners with the shortest screen time". themovies.co.za. The Movies. Archived from the original on 2015-04-05. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- 1 2 Harmetz, Aljean (2004-08-11). "David Raksin, The Composer of 'Laura', Is Dead at 92". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ Miller, Frank (2016). "Behind the Camera on The Bad and the Beautiful". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

As a result, he insisted that the love theme from The Bad and the Beautiful be released strictly as an instrumental. It became a hit[.]

- ↑ "The Bad and the Beautiful". Jazzstandards.com. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Phillips, Michael (2011-08-26). "Anatomy of a Great Movie Theme". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Bad and the Beautiful |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Bad and the Beautiful (film). |

- The Bad and the Beautiful at the Internet Movie Database

- The Bad and the Beautiful at AllMovie

- The Bad and the Beautiful at the TCM Movie Database