ROKS Cheonan sinking

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time | 21:22 Korea Standard Time |

|---|---|

| Date | 26 March 2010 |

| Participants |

|

| Property damage | 1 ROKN corvette sunk, 46 personnel killed, 56 personnel wounded |

| Inquiries | International investigation convened by ROK government, Russian Navy investigation |

| Charges |

ROK-convened (JIG) Investigation concludes that DPRK sank the corvette using a midget submarine-launched torpedo. Investigation results are disputed. North Korea denies involvement. |

| ROKS Cheonan sinking | |

| Hangul | 천안함피격사건 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 天安艦被擊事件 |

| Revised Romanization | Cheonanham Pigyok Sageon |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ch'ŏnanham Pigyŏk Sagŏn |

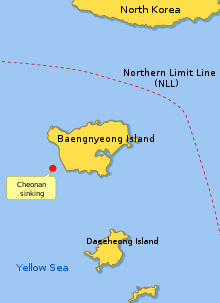

The ROKS Cheonan sinking occurred on 26 March 2010, when Cheonan, a Pohang-class corvette of the Republic of Korea Navy, carrying 104 personnel, sank off the country's west coast near Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea, killing 46 seamen. The cause of the sinking remains in dispute, although overwhelming evidence points to North Korea.

A South Korean-led official investigation carried out by a team of international experts from South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Sweden[2][3] presented a summary of its investigation on 20 May 2010, concluding that the warship had been sunk by a North Korean torpedo[4][5] fired by a midget submarine.[6] The conclusions of the report resulted in significant controversy within South Korea.

North Korea denied that it was responsible for the sinking.[7] North Korea's further offer to aid an open investigation was disregarded.[8] China dismissed the official scenario presented by South Korea and the United States as not credible.[9] An investigation by the Russian Navy also did not concur with the report.[10] The United Nations Security Council made a Presidential Statement condemning the attack but without identifying the attacker.[11]

Background

Baengnyeong Island is a South Korean island in the Yellow Sea, off the Ongjin peninsula in North Korea. It lies less than 10 miles (16 km) from the North Korean coast, and is over 100 miles (160 km) from the South Korean mainland. The island is to the south and west of the Northern Limit Line, the de facto maritime boundary dividing South Korea (ROK) from North Korea (DPRK).

A: United Nations-created Northern Limit Line, 1953[13]

B: North Korea-declared "Inter-Korean MDL", 1999[14] The locations of specific islands are reflected in the configuration of each maritime boundary, including ----

The area is the site of considerable tension between the two states; although it was provided in the armistice agreement for the stalemate of the Korean war that the islands themselves belonged to the South, the sea boundary was not covered by the armistice, and the sea is claimed by the North.

The situation is further complicated by the presence of a rich fishing ground used by DPRK and Chinese fishing vessels, and there have been numerous clashes over the years between naval vessels from both sides attempting to police what both sides regard as their territorial waters. These have been referred to as "crab wars".[15]

History of ship sinkings on both sides

In late May 2010, Bruce Cumings, Distinguished Service Professor in History at the University of Chicago and an expert on Korean affairs, commented that the sinking should be regarded as part of a two-sided tense situation in a "no-man's land" which has led to previous incidents.[16] He noted a confrontation in November 2009, in which several North Korean sailors died, and an additional incident in 1999, when 30 North Koreans were killed and 70 wounded when their ship sank.[16] In both incidents, the North Koreans were the first to open fire, though in the 1999 incident the South Koreans escalated matters by initiating a campaign of boat 'bumping' in order to stop what the South saw as a violation of its maritime borders. Considering these previous incidents, Cumings said that the Cheonan sinking was "ripped out of context, the context of a continuing war that has never ended."[16]

Military concerns

General Walter Sharp, Commander of the South Korea-U.S. Combined Forces Command at the time had, on 24 March, testified before the US House Appropriations Committee, in part, on the need to strengthen the ROK-U.S. alliance, the need for on-site advanced training of the Air Force, the need to improve the quality of life and provide tour normalization for troops serving one-year tours, planned relocation of bases, and the scheduled 2012 transition of Operational Control (OPCON) to ROK hands. He also warned of the possibility that North Korea could "even launch an attack on the ROK."[17]

Sinking of Cheonan

On the night of the sinking the U.S. and South Korea navies were engaged in joint anti-submarine warfare exercises 75 miles away.[18][19][20] This exercise was part of the annual Key Resolve/Foal Eagle war exercise, described as "one of the world's largest simulated exercises", and involved many modern U.S. and South Korean warships.[21][22]

On Friday, 26 March 2010, an explosion was reported to have occurred near Cheonan, a Pohang-class corvette,[23] near the stern of the ship at 9:22 pm local time (12:22 pmGMT/UTC).[24][25] This caused the ship to break in half five minutes afterward, sinking at approximately 9:30 pm(2130 hrs) local time about 1 nautical mile (1.9 km) off the south-west coast of Baengnyeong Island.[26][27][28]

Some initial reports suggested that the ship was hit by a North Korean torpedo, and that a South Korean vessel had returned fire,[29] however the South Korean Ministry of Defense stressed in the first press briefings after the sinking that there was "no indication of North Korean involvement".[30][31] Cheonan was operating its active sonar at the time, which did not detect any nearby submarine.[18] Several theories have subsequently been put forth by various agencies as to the cause of the sinking.[32][33] Early reports also suggested that South Korean navy units had shot at an unidentified ship heading towards North Korea, however a defense official later said that this target may have been a flock of birds that were misidentified on radar.[34]

The ship had a crew of 104 men at the time of sinking, and 58 crewmembers were rescued by 11:13 pm local time.[25] The remaining 46 crew died.[35]

The stern of Cheonan settled on its left side in 130-metre (430 ft) deep water close to the site of the sinking, but the bow section took longer to sink and settled overturned in 20 metres (66 ft) of water 6.4 kilometres (3.5 nmi) away with a small part of the hull visible above the water.[27][35][36]

Rescue efforts

Initially six South Korean navy and two South Korean coast guard ships assisted in the rescue as well as aircraft from the Republic of Korea Air Force.[37] It was reported on March 27 that hopes of finding the 46 missing crew alive were fading. Survival time in the water was estimated at about two hours and large waves were hampering rescue attempts.[38][39] After the sinking, President Lee said that recovery of any survivors was the main priority. Air was pumped into the ship to keep any survivors alive.[40]

During the course of the search and rescue effort over 24 military vessels were involved,[41] including four U.S. Navy vessels, USNS Salvor, USS Harpers Ferry, USS Curtis Wilbur, and USS Shiloh.[20][36][42]

On 30 March 2010 it was reported that one South Korean naval diver had died after losing consciousness whilst searching for survivors and another had been hospitalised.[43]

On 3 April 2010, South Korean officials said that a private fishing boat involved in the rescue operations had collided with a Cambodian freighter, sinking the fishing boat and killing at least two people, with seven reported missing.[44] The same day, the Joint Chiefs of Staff of South Korea said that one body of the 46 missing sailors had been found.[44][45]

Later on 3 April 2010 South Korea called off the rescue operation for the missing sailors, after families of the sailors asked for the operation to be suspended for fear of further casualties among the rescue divers. The military's focus then shifted towards salvage operations, which were predicted to take up to a month to complete.[44]

Recovery

.jpg)

On 15 April 2010, the stern section of the ship was winched from the seabed by a large floating crane, drained of water and placed on a barge for transportation to the Pyongtaek navy base.[46] On 23 April 2010, the stack was recovered,[25] and on 24 April the bow portion was raised.[47] The salvaged parts were taken to Pyongtaek navy base for an investigation into the cause of the sinking by both South Korean and foreign experts.[46]

The bodies of 40 personnel out of 46 who went down with the ship were recovered.[48]

Cause of sinking

Early speculation

South Korean officials initially downplayed suggestions that North Korea was responsible for the sinking.[30] On 29 March 2010, following an underwater examination of the wreck, Defense Minister Kim Tae-Young stated that the explosion may have been caused by a North Korean mine, possibly left over from the Korean War.[41] On 2 April Kim said it was a "likely possibility" that a torpedo had sunk Cheonan.[49]

The South Korean newspaper The Chosun Ilbo reported on 31 March 2010 that a North Korean submarine was observed near the site of the sinking by South Korean and American intelligence agencies.[50] Another report from the same newspaper said that Captain Choi Won-il of the Cheonan made a call on his mobile phone right after the explosion in which he said "We are being attacked by the enemy."[51]

On 30 March 2010, Defense ministry spokesman Won Tae-jae, dismissed speculation that a submarine could have torpedoed the ship, stating that no "extraordinary activities" had been confirmed.[52] On 2 April 2010, The Chosun Ilbo cited unnamed defense agency officers as speculating that a torpedo from a North Korean two-man submersible could have sunk the ship, as there was so far no evidence of an internal explosion.[53]

In a separate statement later the same day, the Defense Ministry said that its investigation had ruled out the possibility of an internal explosion, as testimony from survivors had not supported such a conclusion.[42] The ministry reiterated that it would not speculate on the cause until its investigation was complete.[53]

Director of the Pusan National University Ship Structural Mechanics Laboratory, Jeom Kee Paik,[54] suggested Cheonan may have grounded in the area's shallow water, which is not usually navigated, and took in water from the damaged bottom before breaking in two. South Korean media reports had stated that the hull was found to have split cleanly, suggesting a non-explosive cause.[55]

On 7 April 2010, the chairman of the South Korean National Assembly's Defense Committee, Kim Hak-song, stated that damage to the ship was of a type that is "inevitably the result of a torpedo or mine attack."[56] The same day, National Intelligence Service Director Won Sei-hoon stated that according to their intelligence, and that obtained from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, there was no unusual North Korean activity on the day of the sinking,[57] confirming an earlier similar statement by General Walter Sharp, Commander of the ROK-US Combined Forces.[58]

On 25 April 2010, Defense Minister Kim said that the most likely cause of the explosion that sank Cheonan was a torpedo; his statements were the first time that a South Korean official publicly cited such a cause. Kim said that "A bubble jet caused by a heavy torpedo is thought to be the most likely thing to be blamed, but various other possibilities are also under review." A bubble jet is caused by an underwater explosion which changes the pressure of water, and whose force can cause a ship to break apart. The bubble jet theory was supported by one of the investigators into the incident, who had said that there was no evidence that an explosion had occurred in contact with a ship, and that a non-contact explosion had most likely broken the ship in half.[59]

The Hankyoreh newspaper and other sources have questioned how an anti-submarine corvette such as Cheonan in the middle of a joint South Korean-U.S. naval exercise could have failed to detect an attacking submarine or at least its torpedo.[60]

Investigation

_Navy_2nd_Fleet%2C_and_Rear_Adm._Seung_Joon_Lee%2C_deputy_comman.jpg)

After raising the ship, South Korea and the United States formed a joint investigative team to discover the cause of the sinking.[61] Later South Korea announced that it intended to form an international group to investigate the sinking including Canada, Britain, Sweden and Australia.[62][63]

On 16 April 2010, Yoon Duk-yong, co-chairman of the investigation team, said "In an initial examination of Cheonan's stern, South Korean and U.S. investigators found no traces showing that the hull had been hit directly by a torpedo. Instead, we've found traces proving that a powerful explosion caused possibly by a torpedo had occurred underwater. The explosion might have created a bubble jet that eventually generated an enormous shock wave and caused the ship to break in two."[64] Traces of an explosive chemical substance used in torpedoes, RDX, were later found in May 2010.[65]

The Washington Post reported on 19 May 2010, that a team of investigators from Sweden, Australia, Britain, and the United States had concluded that a North Korean torpedo sank the ship. The team found that the torpedo used was identical to a North Korean torpedo previously captured by South Korea.[66] On 25 April 2010, the investigative team announced that the cause of the sinking was a non-contact underwater explosion.[67]

On 7 May 2010, a government official said that a team of South Korean civilian and military experts[68] had found traces of RDX, a high explosive more powerful than TNT and used in torpedoes.[69] On 19 May 2010, the discovery of a fragment of metal containing a serial number similar to one on a North Korean torpedo salvaged by South Korea in 2003 was announced.[70]

In their summary for the United Nations Security Council, the investigation group was described as the "Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group of the Republic of Korea with the participation of international experts from Australia, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, and the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force, comprising the Republic of Korea, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States," which consisted of "25 experts from 10 top Korean expert agencies, 22 military experts, 3 experts recommended by the National Assembly, and 24 foreign experts constituting 4 support teams".[2]

Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (JIG) report

Summary

On 20 May the South Korean-led investigation group released a summary of their report[3][25][71] in which they concluded that the sinking of the warship was the result of a North Korean torpedo attack, commenting that "The evidence points overwhelmingly to the conclusion that the torpedo was fired by a North Korean submarine." The inquiry also alleged that a group of small submarines, escorted by a support ship, departed from a North Korean naval base a few days before the sinking.[4][72][73][74] The specific weapon used was alleged to be a North Korean manufactured CHT-02D torpedo, of which substantial parts were recovered.[75]

According to the Chosun Ilbo, South Korean investigators told their journalists that they believe that one or two North Korean submarines, a Yono-class submarine and the other a Sang-O-class submarine, departed a naval base at Cape Bipagot accompanied by a support ship on 23 March 2010. One of the subs, according to the report, detoured around to the west side of Baengnyeong Island, arriving on 25 March 2010. There, it waited about 30 metres (98 ft) under the ocean's surface in waters 40 to 50 metres (130 to 160 ft) deep for Cheonan to pass by. Investigators believe that the submarine fired the torpedo from about 3 km away. The attack appears to have been timed for a period when tidal forces in the area were slow. The North Korean vessels returned to port on 28 March 2010.[6] Such detailed information on the North Korean submarine movements, and attack position, was not in the official summary or final report.[76]

The torpedo parts recovered at the site of the explosion by a dredging ship on 15 May which include the 5×5 bladed contra-rotating propellers, propulsion motor and a steering section, was claimed to match the schematics of the CHT-02D torpedo included in introductory brochures provided to foreign countries by North Korea for export purposes. An incorrect, though similar, torpedo schematic had by mistake been shown at the televised RIG briefing for comparison with the recovered parts.[77] The correct schematic has never been made public. The markings in Hangul, which reads "1번" (or No. 1 in English), found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo, but inconsistent with one found seven years ago, which is marked "4호."[60] Critics have pointed out that '호" is the term used most often in the North, rather than "번."[60] Russian and Chinese torpedoes are marked in their respective languages. The CHT-02D torpedo manufactured by North Korea utilizes acoustic/wake homing and passive acoustic tracking methods.[3]

Simulations indicated that 250 kg (550 lb) of TNT equivalent explosive at 6 to 9 metres (20 to 30 ft) depth, 3 metres (9.8 ft) to the port of the center line, would result in the damage seen to Cheonan.[78]

The full report had not been released to the public at this time,[79] though the South Korean legislature was provided with a five-page synopsis of the report.[80]

Full report

A draft copy of the report was obtained by Time magazine in early August 2010, before the final report was released. According to Time, the report assessed eleven different possible reasons why the ship sank, all of which were dismissed except for that of North Korean involvement, which is considered a "high possibility."[79]

In support of this conclusion, the report says that witnesses had reported seeing flashes of light or sounds of an explosion, as well as that the US Navy analysis of the wreck concluded that a torpedo containing 250 kilograms of explosives had collided with Cheonan six to nine meters below the waterline. Damage to the hull supported this conclusion, while inconsistent with what would be expected if the ship had run aground or had been hit with a missile.[79]

On 13 September 2010, the full report was released.[76] It concluded that Cheonan had been sunk due to a torpedo explosion, which, while not having contacted the ship, exploded several meters from the hull of the ship and caused a shockwave and bubble effect of sufficient strength to severely damage and sink the ship.[81]

South Korean opinions

According to a survey conducted by Seoul National University's Institute for Peace and Unification Studies, less than one third of South Koreans trust the findings of the multinational panel.[82][83] A later survey by the JoongAng Ilbo newspaper in 2011 found that 68 percent of South Koreans trusted the government's report that Cheonan was sunk by a North Korean submersible.[84] Lee Jung Hee, a lawmaker with the opposition Democratic Labor Party, was sued for defamation by seven people at South Korea's Joint Chiefs of Staff. Lee said during a speech in the national assembly that while the Defense Ministry had said there was no feed from a thermal observation device showing the moment the warship's stern and bow split apart, such a video did exist. Prosecutors then questioned Shin Sang-cheol, who served on the panel that investigated the incident and also runs Seoprise, over his assertion that Cheonan sank in an accident[85] and that the evidence linking the North to the torpedo was tampered with. The Defense Ministry asked the National Assembly to eject Shin from the panel for "arousing public mistrust."[86][87] Shin stated that he doubted the official conclusion on the sinking, saying that when he looked at the dead sailors' bodies, they bore no signs of an explosion.[80] Shin wrote a letter addressed to US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton showing the evidence for his contention that the ship ran aground and then collided with another vessel.[88]

Russian Navy experts assessment

.jpg)

Near the end of May a team of Russian Navy submarine and torpedo experts visited South Korea to conduct an assessment of the South Korean led investigation. The team returned to Russia with samples for further physical-chemical analysis.[90] No official statement on the assessment has been made. It was claimed that the assessment concluded Cheonan was not sunk by a North Korean bubble jet torpedo, but did not come to any firm conclusion about the cause of the sinking.[91] The Hindu quoted a Russian Navy source stating that "after examining the available evidence and the ship wreckage Russian experts came to the conclusion that a number of arguments produced by the international investigation in favour of the DPRK's involvement in the corvette sinking were not weighty enough”.[92]

On 27 July 2010, The Hankyoreh published what it claimed was a detailed summary of the Russian Navy expert team's analysis.[10] According to The Hankyoreh, the Russian investigators concluded that Cheonan touched the sea floor and damaged one of its propellers prior to a non-contact explosion, possibly caused by setting off a mine while the ship was trying to maneuver into deeper water. Visual examination of the torpedo parts South Korea found purportedly indicated that it had been in the water for more than 6 months.[93] On the following day South Korean officials responded with "a full-scale refutation".[94]

On 3 August 2010 Russian UN ambassador Vitaly Churkin stated that his country's investigative report's conclusions into the sinking would not be made public.[95] Withholding the investigation results was seen as insensitive by South Korea, but avoided political damage to a number of states.[96]

Chinese claims

During talks between the American and Chinese governments in late May 2010, Chinese officials were reported by Yoichi Shimatsu, a commentator for the Chinese state-run CCTV-9, to have claimed that the sinking of Cheonan had been as a result of an American rising mine, which was moored to the seabed and propels itself into a ship detected by sound or magnetics, planted during anti-submarine exercises that were conducted by the South Korean and US navies shortly before the sinking. To back up their claims, the Chinese said that North Korean submarines such as the one believed to have sunk Cheonan were incapable of moving undetected within South Korean waters, and a rising mine would have damaged the ship by splitting the hull, as was done to Cheonan, rather than simply holing the vessel as a conventional torpedo does. A conventional torpedo traveling at 40–50 knots (74–93 km/h; 46–58 mph) would also be completely destroyed upon impact, which was claimed to contradict the torpedo parts found later.[9]

The Daily Telegraph journalist Peter Foster in a blog post noted that while not everyone (including Russia and China) was convinced of the truth of the international inquiry into the ROKS Cheonan Sinking, some conspiracy theories and unanswered questions on the sinking, including one ascribing responsibility of the sinking to a rising mine deployed during a joint US-South Korean Foal Eagle anti-submarine exercises, ought to be read "with a large pinch of salt."[97]

Other international research

A separate investigation conducted by scientists at the University of Manitoba yielded results that conflict with the official investigation's findings. According to the leader of the investigation, residue on the hull of the ship that was claimed to have been aluminum oxide, which is a byproduct of explosions such as that of a torpedo, had a far higher ratio of oxygen to aluminum, leading the researchers to conclude that "we cannot say that the substance adhering to the Cheonan was the explosion byproduct of aluminum oxide."[98] The South Korean Ministry of Defense issued a rebuttal to the findings, saying, "The detonation of explosives containing aluminum occurs within hundreds of thousandths of a second under high temperatures of more than 3,000 degrees Celsius and high pressures of more than 200,000 atm, and most of it becomes noncrystalline aluminum oxide."[98]

A report published online by Nature on 8 July 2010 noted several instances of groups or individuals disagreeing with the official report.[32][99] The article also notes the rebuttal of those disagreements by analysts and government officials, with one analyst arguing that the sinking was "consistent with North Korea's behaviour in the past."[32]

In 2013 an academic paper was published analysing the available seismic data. It calculated that the sesmic data recorded would be accounted for by a 136 kg (300 lb) TNT-equivalent charge, similar to the explosive yield of land control mines which had been abandoned in the vicinity.[100][101] In 2014 an academic paper was published analysing the spectra of the seismic signals and hydroacoustic reverberation waves generated. The paper found it doubtful that the vibrations of the water column were caused by an underwater explosion, instead finding that the recorded seismic spectra were consistent with the natural vibration frequencies of a large submarine with a length of around 113 metres (371 ft). This raised the possibility that the sinking was caused by a collision with a large submarine, rather than an explosion.[102]

Reaction

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of North Korea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

South Korea

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak convened an emergency meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Orders were given to the military to concentrate on rescuing the survivors. In Seoul, police were put on alert. At the time, a spokesman for the South Korean military stated that there was no evidence that North Korea had been involved in the incident.[26] A large group of relatives of the missing sailors protested outside the navy base at Pyeongtaek over the lack of information provided to them.[38] On 28 March relatives were taken to the site of the sunken vessel. Some relatives stated that survivors had claimed that the Cheonan had been in a poor state of repair.[28] The Korean media have raised the issue of why the sister ship Sokcho, which was operating nearby, did not come to the rescue of the sinking ship but instead fired shots at radar images which were later confirmed to be migratory birds.[103]

On 5 April 2010, President Lee Myung-bak visited Baengnyeong Island. He reiterated that it was risky to speculate over the cause, and the joint military and civilian investigation team would determine the cause. He said, "We have to find the cause in a way that satisfies not only our people but also the international community".[104] The president of South Korea has mourned the victims and said that he will respond "resolutely" to the sinking without yet laying blame for its cause.[105]

On 24 May Lee Myung-bak said the South would "resort to measures of self-defense in case of further military provocation of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea." He also supported readopting the official description of the North as the "main enemy."[106]

South Korea pursued measures from the United Nations Security Council after the incident, although the language used in the country's statements towards such measures became progressively weaker. In announcements made soon after the sinking, the government said that any draft presented by South Korea would explicitly state that North Korea was responsible for the incident, but by early July, the language had been reduced to only referring to "those responsible," in response to concerns from Russia.[107]

Diplomatic

Since the incident, the South Korean government has been reluctant to engage in further diplomacy with North Korea over disputes such as North Korea's nuclear weapons program. In response to a request by China, in April 2011 South Korea agreed to talks, but South Korean government officials commented that an apology from North Korea for the sinking would probably be necessary to facilitate any significant progress in the dialogues.[108]

Military

On 2 May it was reported that South Korea's naval minister vowed "retaliation" against those responsible.[109] Admiral Kim Sung-chan, at a publicly televised funeral for Cheonan's dead crew members in Pyeongtaek, stated that, "We will not sit back and watch whoever caused this pain for our people. We will hunt them down and make them pay a bigger price."[110]

On 4 May President Lee proposed "extensive reformations" for the South Korean military regarding the sinking incident.[111] After the official report was released South Korea has said that it will take strong countermeasures against the North.[112]

Trade

On 24 May 2010, South Korea announced it would stop nearly all its trade with North Korea as a result of the official report blaming North Korea for the sinking. South Korea also announced it would prohibit North Korean vessels from using its shipping channels.[113] According to the New York Times, the trade embargoes were "the most serious action" South Korea could take short of military action.[114] The United States openly supported South Korea's decision.[115] The embargo is expected to cost the North Korean economy roughly $200 million a year.[116] The decision to cease trade was followed up with the United States and South Korea announcing they would conduct joint naval exercises in response to the sinking.[117]

Psychological warfare

The South Korean military announced that it would resume psychological warfare directed at North Korea. This would include both loudspeaker and FM radio propaganda broadcasts across the DMZ. Meanwhile, a North Korean military commander stated, “If South Korea establishes new psychological warfare services, we will fire against them in order to eliminate them,” according to a report carried by the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA).[118]

South Korea began propaganda broadcasts into North Korea by radio on 25 May. North Korea responded by putting its troops on high alert, and severed most remaining ties and communications with South Korea in response to what it called a "smear campaign" by Seoul.[119] South Korean military propaganda FM broadcasts were resumed at 18:00 (local time) starting with the song "HuH" by K-pop band 4minute.[120]

As part of the propaganda broadcasts, South Korea reinstalled loudspeakers at eleven places along the DMZ. There was originally a plan to also use electronic signs, although due to cost, the plan was reportedly being reconsidered. On 13 June, South Korean media announced that the South Korean Defense Minister, Kim Tae-young, had said that anti-North Korea broadcasts were planned to resume after the UN Security Council took action against North Korea in response to the sinking of Cheonan.[121]

Suppressing internal dissent

Discourse over the events leading to the sinking of Cheonan was tightly controlled by the South Korean government in the months after the incident. On 8 May 2010, a former senior presidential secretary who served under Roh Moo-hyun, Park Seon-won,[122] was charged with libel by South Korea's Defense Minister, Kim Tae-young, over comments he made during a 22 April interview on MBC radio asking for greater disclosure from the military and government. Park Seon-won's response to the charge was: "I asked for the disclosure of information for a transparent and impartial investigation into the cause of the Cheonan sinking;" he added that "the libel suit seeks to silence public suspicion over the incident."[123] South Korea's Minister of Public Administration and Security, Maeng Hyung-kyu, announced on 20 May 2010 that the government was stepping up efforts to prosecute people who spread "groundless rumors" over the internet: "Anyone who makes false reports or articles about the incident could seriously damage national security. We will not let these be the basis of any risks the nation faces." Moreover, he announced the government would step up efforts to prevent "illegal gatherings" regarding the sinking of Cheonan.[124]

A South Korean military oversight board, the Board of Inspection and Audit, has accused senior South Korean naval leaders of lying and hiding information. Said the board, "Military officers deliberately left out or distorted key information in their report to senior officials and the public because they wanted to avoid being held to account for being unprepared."[80]

In 2013, a documentary film named "Project Cheonan Ship" was released in South Korea about the sinking, including a number of possible alternative causes for the sinking. Members and relatives of the South Korean navy sought a court injunction to block the film’s release on the basis that the film distorted the facts. The injunction was denied in court, however, a major cimema chain, Megabox, withdrew the film after warnings from conservative groups that they planned to picket showings the film.[125][126]

North Korea

The North Korean Central News Agency released an official response to the investigation on 28 May 2010, asserting, amongst other things, that it is unbelievable that part of a torpedo doing so much damage to a ship would survive:

"Besides, the assertion that the screw shaft and engine remained undamaged and unchanged in shape is also a laughing shock. Even U.S. and British members of the international investigation team, which had blindly backed the south Korean regime in its 'investigation', were perplexed at the exhibit in a glass box."[127]

On 17 April 2010, it was reported that North Korea officially denied having had anything to do with the sinking, responding to what it referred to as "The puppet military warmongers, right-wing conservative politicians and the group of other traitors in South Korea".[128] An article from the official (North) Korean Central News Agency entitled "Military Commentator Denies Involvement in Ship Sinking" stated that the event was an accident.

... we have so far regarded the accident as a regretful accident that should not happen in the light of the fact that many missing persons and most of rescued members of the crew are fellow countrymen forced to live a tiresome life in the puppet army.[129]

On 21 May 2010, North Korea offered to send their own investigative team to review the evidence compiled by South Korea,[130] and the Hankyoreh quoted Kim Yeon-chul, professor of unification studies at Inje University, commenting on the offer: "It is unprecedented in the history of inter-Korean relations for North Korea to propose sending an investigation team in response to an issue that has been deemed a 'military provocation by North Korea,'"and thus "The Cheonan situation has entered a new phase."[131]

The North also warned of a wide range of hostile reactions to any move by the South to hold it accountable for the sinking.

If the South puppet group comes out with 'response' and 'retaliation', we will respond strongly with ruthless punishment including the total shutdown of North-South ties, abrogation of the North-South agreement on non-aggression and abolition of all North-South cooperation projects.[132]

On 24 May, new reports indicated Kim Jong-Il had ordered the North's forces to be ready for combat a week before.[133] The next day, North Korea released a list of measures that it will take in response to South Korea's sanctions. This would include the cutting of all ties and communications, except for the Kaesong industrial complex. They would revert to a wartime footing in regard to South Korea and disallow any South Korean ships or aircraft to enter the territory of North Korea.[134]

On 27 May, North Korea announced that it would scrap an agreement aimed at preventing accidental naval clashes with South Korea. It also announced that any South Korean vessel found crossing the disputed maritime border would be immediately attacked.[135]

On 28 May, the official (North) KCNA stated that "it is the United States that is behind the case of Cheonan. The investigation was steered by the U.S. from its very outset." It also accused the United States of manipulating the investigation and named the administration of US President Barack Obama directly of using the case for "escalating instability in the Asia-Pacific region, containing big powers and emerging unchallenged in the region."[136]

On 29 May, North Korea warned the United Nations to be wary of evidence presented in the international investigation, likening the case to the claims of weapons of mass destruction that the U.S. used to justify its war against Iraq in 2003 and stated that "the U.S. is seriously mistaken if it thinks it can occupy the Korean Peninsula just as it did Iraq with sheer lies." The North Korea foreign minister warned the United Nations Security Council of risks of being "misused". It also accused the U.S. of joining South Korea in putting "China into an awkward position and keep hold on Japan and South Korea as its servants." High ranking North Korean military officials denounced the international investigation and said the North does not have the type of submarines that supposedly carried out the attack. They also dismissed claims regarding writings on the torpedo and clarified that "when we put serial numbers on weapons, we engrave them with machines." South Korea's Yonhap News quoted South Korean officials as saying the North has about 10 of the Yeono-class submarines.[87]

On 2 November, KCNA published a detailed rebuttal of the South Korean joint investigative team report.[137]

The Rodong Sinmun claimed that the "probability of a torpedo attack on (the) Cheonan Warship" was 0%.[138]

International

When the official report on the sinking was released on 20 May there was widespread international condemnation of the North's actions. China was one of few exceptions, simply terming the incident "unfortunate" and "urged stability on the peninsula". This was speculated to be China's concern for instability in the Korean peninsula.[112]

On 14 June 2010, South Korea presented the results of its investigation to United Nations Security Council members.[2][139] In a subsequent meeting with council members North Korea stated that it had nothing to do with the incident.[140] On 9 July 2010 the United Nations Security Council made a Presidential Statement condemning the attack but without identifying the attacker.[11][141] China had resisted U.S. calls for a tougher line against North Korea.[142]

Later reports

A member of the North Korean cabinet who defected to the south in 2011, said on 7 December 2012 that the crew of the North Korean submarine which sank Cheonan had been honored by the North Korean military and government. The defector, known by the alias "Ahn Cheol-nam", stated that the captain, co-captain, engineer, and boatswain of the mini-sub which sank Cheonan had been awarded "Hero of the DPRK" in October 2010.[143]

See also

- Korean Air Flight 858

- Korean War

- Bombardment of Yeonpyeong

- List of border incidents involving North Korea

References

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Park In-kook (4 June 2010), "Letter dated 4 June 2010 from the Permanent Representative of the Republic of Korea to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF), United Nations Security Council, S/2010/281, retrieved 11 July 2010

- 1 2 3 "Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS Cheonan – report statement". Ministry of National Defense R.O.K. 20 May 2010. News item No 592. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 "Results Confirm North Korea Sank Cheonan". Daily NK. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Barrowclough, Anne (20 May 2010). "'All out war' threatened over North Korea attack on warship Cheonan". The Times. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- 1 2 "How Did N. Korea Sink The Cheonan?". Chosun Ilbo. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ↑ "Press Conference on Situation in Korean Peninsula: DPRK Permanent Representative to the United Nations Sin Son Ho". Department of Public Information. United Nations. 15 June 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Watson Paul (19 July 2012). South Korea good, North Korea bad? Not a very useful outlook. The Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- 1 2 Yoichi Shimatsu, (27 May 2010). "Did an American Mine Sink South Korean Ship?". New America Media. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- 1 2 "Presidential Statement: Attack on Republic of Korea Naval Ship 'Cheonan'". United Nations Security Council. United Nations. 9 July 2010. S/PRST/2010/13. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Ryoo, Moo Bong. (2009). "The Korean Armistice and the Islands," p. 13 (at PDF-p. 21). Strategy research project at the U.S. Army War College; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- ↑ "Factbox: What is the Korean Northern Limit Line?" Reuters (UK). 23 November 2010; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- ↑ Van Dyke, Jon et al. "The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea," Marine Policy 27 (2003), 143–158; note that "Inter-Korean MDL" is cited because it comes from an academic source, Archived 9 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF), and the writers were particular enough to include in quotes as we present it. The broader point is that the maritime demarcation line here is NOT a formal extension of the Military Demarcation Line; compare "NLL—Controversial Sea Border Between S.Korea, DPRK, " People's Daily (PRC), 21 November 2002; retrieved 22 Dec 2010

- ↑ "Northern Limit Line (NLL) West Sea Naval Engagements". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Historian Bruce Cumings: US Stance on Korea Ignores Tensions Rooted in 65-Year-Old Conflict; North Korea Sinking Could Be Response to November '09 South Korea Attack". Democracy Now!. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ↑ "Statement of General Walter L. Sharp, commander, United Nations command; commander, Republic of Korea-United States combined forces command; and commander, United States forces Korea, before the House Appropriations Committee, MILCON/Veterans Affairs subcommittee, 24 March 2010" (PDF). Committee on Appropriation, US House of Representatives. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- 1 2 Jelinek, Pauline (5 June 2010). "AP Enterprise: Sub attack was near US-SKorea drill - Boston.com". The Boston Globe. Jean H. Lee and Kwang-Tae Kim in Seoul contributed to this report. Boston: NYTC. Associated Press. ISSN 0743-1791. OCLC 66652431. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ Associated Press (5 June 2010). "'Sub Attack Came Near Drill'". military.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- 1 2 "U.S. Support to ROK Salvage Operations Changes Leadership". Amphibious Force Seventh Fleet Public Affairs. 4 April 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Lance Cpl. Claudio A. Martinez (11 March 2010). "Exercises Key Resolve/Foal Eagle 2010 kick off". U.S. Marine Corp. Archived from the original on 2010-06-05. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ Kim Myong Chol (5 May 2010). "Pyongyang sees US role in Cheonan sinking". Asia Times Online. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ "Report: South Korean navy ship sinks". CNN. 27 March 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "Chronology of the Cheonan Sinking". Korea Times. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Investigation Activities on the Sinking of ROKS "Cheonan" – investigation video". Ministry of National Defense R.O.K. 20 May 2010. Linked from news item No 592. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 "South Korean navy ship sinks near sea border with North". BBC. 26 March 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Poor weather halts search of South Korea sunken warship". BBC. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- 1 2 Mark TranSi-Young Lee and Hyung-Jin Kim (28 March 2010). "Angry families visit site of sunken SKorean ship". Associated Press. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ↑ Kim Sengupta (27 March 2010). "Warship mystery raises Korean tensions". The Independent. London.

- 1 2 "South Korea urges restraint over sunken warship". BBC News. 1 April 2010.

- ↑ "Businessweek - Business News, Stock market & Financial Advice". Businessweek.com. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Controversy over South Korea's sunken ship". Nature. 8 July 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ Gregg, Donald P. (31 August 2010). "Testing North Korean Waters". The New York Times.

- ↑ Tania Branigan and Caroline Davies (26 March 2010). "South Korean naval ship sinks in disputed area after 'explosion'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- 1 2 Evan Ramstad (29 March 2010). "Divers Reach South Korean Wreckage". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- 1 2 Edward Baxter (May 2010). "Salvor supports recovery of South Korean navy ship" (PDF). Sealift. Military Sealift Command, U.S. Navy. p. 3. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Crilly, Rob (26 March 2010). "South Korea investigates whether North involved in ship sinking". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Hopes fading for South Korea sailors". BBC News. 27 March 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Lee, Tae-hoon (28 March 2010). "More Questions Raised Than Answered Over Sunken Ship". The Korea Times. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ↑ South Korea rules out navy ship sunk by North Korea, Reuters, Jo Yonghak, 27 March 2010

- 1 2 "Sunken section of South Korean naval vessel found". BBC News. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- 1 2 "South Koreans hold out hope for sailors missing after ship explosion". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "Diver dies at South Korean warship rescue site". BBC News. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 Kwang-Tae Kim (3 April 2010). "SKorea stops underwater search for missing sailors". The Associated Press. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "Nine missing as S Korean boat sinks in warship search". BBC News. 3 April 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- 1 2 "Stern of South Korea naval ship lifted from sea bed". BBC News. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ↑ Lee, Tae-hoon (23 April 2010). "Front Half of Cheonan to Be Raised Today". Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "Asia-Pacific — Funeral held for S Korean sailors". Al Jazeera English. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea says torpedo may have sunk navy ship". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "N. Korean Submarine 'Left Base Before the Cheonan Sank'". The Chosun Ilbo. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cheonan Captain 'Reported Attack'". The Chosun Ilbo. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea urges restraint over sunken warship". BBC. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- 1 2 The Chosun Ilbo, "Suspicion Of N. Korean Hand In Sinking Mounts", 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Dr. Jeom Paik, MarineTalk Advisory Board". MarineTalk. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Kim Jae-Hwan (1 April 2010). "South Korea hunts for clues to warship disaster". AFP. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Lawmaker Points to Signs Linking N. Korean Sub to Shipwreck". The Chosun Ilbo. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ "NIS says N. Korean attack on Cheonan impossible sans Kim Jong-il approval". Hank Yoreh. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Hyung-Jin Kim (6 April 2010). "U.S., S. Korea to jointly probe ship sinking". Navy Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe (25 April 2010). "South Korea Cites Torpedo Attack in Ship Sinking". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Questions raised following Cheonan announcement". The Hankyoreh. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "INSIDE JoongAng Daily". Joongangdaily.joins.com. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ (AFP) – 12 Apr 2010 (12 April 2010). "AFP: Australians to join probe into S.Korea warship sinking". Google. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Canadian Naval Expertise to Assist in Multinational Investigation into the Cheonan Sinking". Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. 16 May 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ↑ Jung Sung-ki (19 April 2010). "N. Korean Submarines Pose Grave Threat to Security". Seoul: Korea Times. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "S. Korea confirms detection of explosive chemical in sunken warship". Xinhua. 10 May 2010.

- ↑ Pomfret, John; Harden, Blaine (19 May 2010). "South Korea to officially blame North Korea for March torpedo attack on warship". Washington Post. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Cheonan Analysis Reveals Non-Contact Cause". Daily NK. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Excerpts: South Korea ship sinking report, BBC, 20 May 2010

- ↑ Explosives from torpedo found on sunken ship, by Lee Tae-hoon Korea Times, 7 May 2010

- ↑ "Probe IDs torpedo that sunk Cheonan: sources". JoongAng Daily. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS Cheonan – Press Summary (PDF). The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (Report). Ministry of National Defense R.O.K. / BBC. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "World News Australia — North Korea 'sank South Korean ship'". Sbs.com.au. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "North Korea denies sinking warship; South Korea vows strong response". CNN. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Foster, Peter; Moore, Malcolm (20 May 2010). "North Korea condemned by world powers over torpedo attack". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 "Joint Investigation Report On the Attack Against the ROKS Ship Cheonan" (PDF), Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of Korea, September 2010, ISBN 978-89-7677-711-9, retrieved 4 December 2010

- ↑ Kim Deok-hyun (29 June 2010). "Investigators admit using wrong blueprint to show N. Korean torpedo that attacked Cheonan". Yonhap. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ↑ ""Smoking Gun" Briefing Slides". South Korean Ministry of Defense. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010. (PDF version of partial slide set)

- 1 2 3 Powell, Bill (13 August 2010). "South Korea's Case for How the Cheonan Sank". Time. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Barbara Demick and John M. Glionna (23 July 2010). "Doubts surface on North Korea's role in ship sinking". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ "Seoul reaffirms N. Korea's torpedo attack in final report". Korea Times. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ↑ "The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition): Daily News from Korea - Most S.Koreans Skeptical About Cheonan Findings, Survey Shows". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Study: Many South Koreans are skeptical of investigators' report on Cheonan sinking". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Christine Kim (22 March 2011). "1 year later, Cheonan still unresolved". JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ S. C. Shin (26 May 2010). "Opinion about Accident of PCC-772" (PDF). Seoprise. Retrieved 8 July 2010. (HTML version)

- ↑ Ser Myo-ja (20 May 2010). "Probe member summoned on false rumor allegations". JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- 1 2 South Korea Faces Domestic Skeptics Over Evidence Against North, by Ben Richardson and Saeromi Shin, Bloomberg News, 30 May 2010

- ↑ "Letter to Hillary Clinton, U.S. Secretary of State". Seoprise.com. 26 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Kwon Hyuk-chul (5 November 2010). "Clamshell covered in white substance discovered on Cheonan torpedo fragment". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ "Russian experts inspect to probe Cheonan issue at home". RIA Novosti. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ↑ Lee Yeong-in (10 July 2010). "Government protests Russia's Conflicting Cheonan findings". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ↑ Vladimir Radyuhin (9 June 2010). "Russian probe undercuts Cheonan sinking theory". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ↑ Yonhap, "Moscow Not To Make Public Probe Outcome On Cheonan's Sinking: Amb. Churkin", 5 August 2010.

- ↑ Sunny Lee (12 October 2010). "Why Russia doesn't share its Cheonan results with Seoul". Seoul: Korea Times. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ "Cheonan sinking: top ten conspiracy theories". The Daily Telegraph. London. 4 June 2010.

- 1 2 "Scientists question Cheonan investigation findings". The Hankyoreh. 28 June 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ Seunghun Lee and J.J. Suh (15 July 2010). "Rush to Judgment: Inconsistencies in South Korea's Cheonan Report". Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. Policy Forum 10-039. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ So Gu Kim, Yefim Gitterman (10 August 2012). "Underwater Explosion (UWE) Analysis of the ROKS Cheonan Incident". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 170 (4). doi:10.1007/s00024-012-0554-9. ISSN 0033-4553. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ Kang Tae-Ho (14 September 2012). "New evidence that Cheonan was sunk by an old mine". Hankyoreh. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Hwang Su Kim and Mauro Caresta (20 November 2014). "What Really Caused the ROKS Cheonan Warship Sinking?". Advances in Acoustics and Vibration. doi:10.1155/2014/514346. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "Military Under Fire – Questions Grow Over Crisis Management Capability". Seoul: Korea Times. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Na Jeong-ju (5 April 2010). "Lee Warns Against Speculation Over Cheonan". Seoul: Korea Times. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea mourns victims of ship sinking". BBC News. 26 April 2010.

- ↑ "ROK president gives nod to calling DPRK "main enemy"". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Requested Security Council Cheonan measures weaken considerably". The Hankyoreh. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ The Korea Herald, "Seoul Insists On N. Korea Apology Before Dialogue", 18 April 2011; Yonhap, "Seoul Renews Demand For N. Korea's Responsible Steps Over Deadly Attacks", 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "S. Korea minister vows retaliation over warship sinking". Hindustan Times. 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ The Korea Herald, "Navy Chief Vows Revenge For Cheonan", 30 April 2010.

- ↑ 김 (Kim), 대우 (Dae-u) (4 May 2010). "작전,무기,군대조직,문화도 다바꿔라" 軍 전방위 개혁 예고 ["Change All Of Plans, Weapons, Organization, Culture" Military Announces Omni-directional Reform]. Herald Economics (in Korean). Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- 1 2 "North Korea accused of sinking ship". 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ Choe Sang-Hun (24 May 2010). "South Korea cuts trade ties with North over sinking". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Choe Sang-Hun; Shanker, Thom (24 May 2010). "Pentagon and U.N. Chief Put New Pressure on N. Korea". New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Lewis, Leo (24 May 2010). "South Korea bans all trade with North over Cheonan attack". The Times. London. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ "US backs South Korea in punishing North Korea". News.yahoo.com. 26 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "US to conduct naval training exercises with S Korea after attack". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Kim So Yeol (24 May 2010). "Psychological Warfare Will Resume". Daily NK. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/on_re_as/as_korea_ship_sinks. Retrieved 25 May 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "South Korea resumes border propaganda broadcast with 4minute!". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "S. Korea reconsiders installing electronic signboards against N. Korea". Yonhap. 13 June 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Korean newspapers have romanized his name as Park Seon-won; however, papers he published while as a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution indicate he romanizes his name as Sun-won Park.

- ↑ "Ex-Pres. Secretary Sued for Spreading Cheonan Rumors". 8 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "Gov't warns against 'groundless rumors'". 20 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea: Film raises questions about Cheonan sinking". Index on Censorship. 17 September 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Jeyup S. Kwaak (5 September 2013). "Controversial Film About Warship Sinking Opens in Theaters". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ "Military Commentator on Truth behind "Story of Attack by North"". (North) Korean News. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ Miyoung Kim (17 April 2010). "North Korea denies it sank South's navy ship". Reuters. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Military Commentator Denies Involvement in Ship Sinking ", Korean Central News Agency. 17 April 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ The Hankyoreh, "N. Korea's Reinvestigation Proposal Alters Cheonan Situation", 21 May 2010.

- ↑ "N. Korea's reinvestigation proposal alters Cheonan situation". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Miyoung Kim (21 May 2010). "North Korea declares phase of war with south". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ "Asia-Pacific – S Korea resumes border broadcasts". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ Thatcher, Jonathan (25 May 2010). "Text from North Korea statement". Reuters. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ BBC (27 May 2010). "North Korea scraps South Korea military safeguard pact". BBC. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ↑ DPRK accuses U.S. of cooking up, manipulating "Cheonan case", by Xiong Tong, Xinhua News Agency, 28 May 2010

- ↑ ""Cheonan" Case Termed Most Hideous Conspiratorial Farce in History". KCNA. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Ri Song Ho (28 June 2012). "Probability of Torpedo Attack on Cheonan Warship: 0%". rodong.rep.kp. Rodong Sinmun. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "North Korea – Developments at the UN". Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations. July 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Sin Son Ho (8 June 2010), "Letter dated 8 June 2010 from the Permanent Representative of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF), United Nations Security Council, S/2010/294, retrieved 11 July 2010

- ↑ Harvey Morris (9 July 2010). "North Korea escapes blame over ship sinking". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Andrew Jacobs and David E. Sanger (29 June 2010). "China Returns U.S. Criticism Over Sinking of Korean Ship". New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ JoongAng Ilbo, N. Korean Sailors Awarded Hero's Title For Attack On S. Korean Warship: Defector, 8 December 2012

Further reading

- Van Dyke, Jon M., Mark J. Valencia and Jenny Miller Garmendia. "The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea," . Marine Policy 27 (2003), 143–158.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Joint Investigation Report On the Attack Against the ROKS Ship Cheonan, Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of Korea, September 2010, ISBN 978-89-7677-711-9

- Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS Cheonan, Press Summary by The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group

- South Korean Ministry of Defense "Smoking Gun" Briefing Slides

- Investigation MND briefing slides

- Briefing – the Cheonan Situation, Ambassador Han Duk-soo, 25 May 2010

Coordinates: 37°55′45″N 124°36′02″E / 37.92917°N 124.60056°E