Qal'at al-Bahrain

| قلعة البحرين | |

Overview of the Bahrain Fort. | |

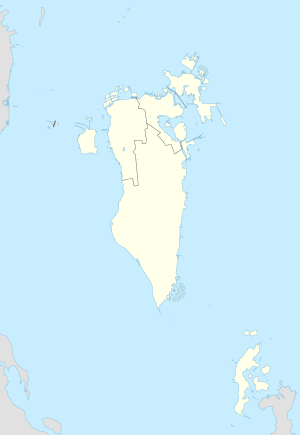

Shown within Bahrain | |

| Location | Capital Governorate, Bahrain |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 26°14′01″N 50°31′14″E / 26.23361°N 50.52056°ECoordinates: 26°14′01″N 50°31′14″E / 26.23361°N 50.52056°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 2300 BC |

| Abandoned | 16th century AD |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Qal`at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 2005 (29th session) |

| Reference no. | 1192 |

| Region | Arab States |

The Qal'at al-Bahrain (in Arabic: قلعة البحرين), also known as the Bahrain Fort or Fort of Bahrain and previously as the Portugal Fort (Qal'at al Portugal)[1] is an archaeological site located in Bahrain, on the Arabian Peninsula. Archaeological excavations carried out since 1954 have unearthed antiquities from an artificial mound of 12 m (39 ft) height containing seven stratified layers, created by various occupants from 2300 BC up to the 18th century, including Kassites, Greeks, Portuguese and Persians. It was once the capital of the Dilmun civilization and was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.[2][3]

History and explorations

The archaeological findings, which are unearthed in the fort, reveal much about the history of the country. The area is thought to have been occupied for about 5000 years and contains a valuable insight into the Copper and Bronze Ages of Bahrain.[4] The first Bahrain Fort was built around three thousand years ago, on the northeastern peak of Bahrain Island. The present fort dates from the sixth century AD.[5] The capital of the Dilmun civilization, Dilmun was, according to the Epic of Gilgamesh, the "land of immortality", the ancestral place of Sumerians and a meeting point of gods.<ref name="Whelan1983

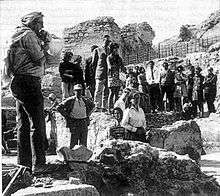

The site has been termed as Bahrain's "most important site in antiquity". The first excavation at the site was carried out by a Danish led by Geoffrey Bibby between 1954 and 1972, and later by a French expedition from 1977.[6] Since 1987 Bahrain archaeologists have been involved with this work. The archaeological findings have revealed seven civilizations of urban structures beginning with Dilmun empire, the most important ancient civilization of the region.[7] The Danish expedition revealed that it was a notable Hellenistic site.[8]

Geography

The fort and the tell Qal'at al-Bahrain is built on, are located on the Bahrain island, on the northern seashore. On a clear day it is also seen from Saar. It stands like a "sentinel" near Manama, the capital of Bahrain; it is 6 km (4 mi) away from Manama on the fertile north coast.[7][9] The tell is the largest in the Persian Gulf region and was built close to the port and by reclamation of seashore land. Qal'at al-Bahrain

Description

Qal`at al-Bahrain is a typical tell – an artificial mound created by many successive layers of human occupation. The strata spreads over a 180,000 sq ft (16,723 m2) area, which encompasses the tell. This testifies to a continuous human presence from about 2300 BC to the 16th century AD. About 25% of the site has been excavated revealing structures of different types:[2] residential, public, commercial, religious and military. They testify to the importance of the site as a trading port over the centuries. On the top of the 12-metre-high (39 ft) mound, there is the impressive Qal`at al-Burtughal (Portuguese fort), which gave the whole site its name, qal`a, meaning "fort". As the site was the capital of the Dilmun civilisation, it contains the richest remains of this civilization, which was hitherto only known from written Sumerian references.[2][3]

The site contains many areas and walls, including Saar necropolis, Al-Hajjar necropolis, Kassite Palace, Madimat Hermand necropolis, Madimat Isa necropolis, Al-Maqsha Necropolis, Palace of Uperi, Shakhura necropolis, and the Northern city wall.[10] The ruins of the Copper Age consists of two sections of the fortification wall surrounding streets and houses, and a colossal building on the edge of the moat of the Portuguese fort in the centre.[4] Barbar pottery has been unearthed around the walls of the central building, dating back to the same age as the Barbar Temples, although some of the other pottery and range of unearthed artefacts indicated that they predated the temples, dating back to 3000 BC or later.[4] Relics of copper and ivory provide an insight into ancient trade links.[4] Many vessels have been unearthed on the site, and Danish excavations of the Palace of Uperi area revealed "snake bowls", sarcophagi, seals and a mirror, among other things.[10]

Layout

The excavations of the tel has revealed a small settlement, the only one of that period in eastern Arabia, on its northern side. It has been inferred that the village was settled by people who developed agriculture near the oasis, planted palm trees, tended cattle, sheep and goats and also ventured into fishing in the Arabian Sea. The small houses they built were made of rough stone with clay or mortar as binding material. The plastered floors in the houses were said to have been spacious. Excavations also hinted that the village had streets which separated the housing complexes.[11]

The fortifications seen in the excavated tel area were found around the township and were erected in cardinal directions. The fort walls are seen now only in the northern, western and southern slopes of the tel, and the eastern side is yet to be excavated. The fortifications covered an area of 15 ha (37 acres), and the walls were built with varying thickness by using stone masonry, and had gates which allowed transport and passing through, such as of donkey caravans. The fortifications were frequently raised, as noted from the gates erected at four levels; the latest gate had two polished stone (made of fine grained material) pivots which fixed a double leafed gate. The western wall was seen well-preserved for a length of 9 m (30 ft). The streets were laid in north–south direction and were 12 m (39 ft) wide.[11]

There was a palace in the centre of the tel at a commanding location consisting of several warehouses which were inferred as indicative of economic activity during the Dilmun period. Proceeding from here towards the north, along the street leads, to a large gate that probably was the entry to the palace grounds. The modest houses built in the same size and type of construction were laid along a network of roads.[11]

The place prospered till 1800 BC after when it was deserted. Eventually the town became covered with drift sand from the sea.[11]

Antiquaries

Metal artifacts found in the tel were limited to copper pieces, fishing tools and a socketed spearhead; a workshop of 525 m (1,722 ft) size was also identified where copper casting two piece moulds and wax moulds were found. Small and large crucibles used for melting of metal were recovered in substantial quantities indicative of large scale manufacture by professional artisans. The copper ware was then traded in surrounding countries such as Oman and Mesopotamia. Dilmun stamp seals were also recovered from the excavations.[11]

Pots and vessels were also recovered. Pots were used for cooking, while the large vessels for food import from Oman and Mesopotamia. Artifacts found there indicates the location. These include a cuneiform inscription and hematite, both of which link to Mesopotamia; steatite bowls to Oman; and carnelian beads, a stone weight and a few potsherds to the Indus Civilization.[11]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qal'at al-Bahrain. |

References

- ↑ Axworthy pp.175–274

- 1 2 3 "Qal'at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- 1 2 "Qal'at al-Bahrain (Bahrain) no 1192" (pdf). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Whelan, John (April 1983). Bahrain: a MEED practical guide. Middle East Economic Digest. pp. 17 et seqq. ISBN 978-0-9505211-7-6. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Cavendish, Marshall (September 2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Boucharlat, Rémy (1984). Arabie orientale, Mésopotamie et Iran méridional: de l'âge du fer au début de la période islamique. Éditions Recherche sur les civilisations. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- 1 2 Dr Mike Hill. Wildlife of Bahrain. Miracle Graphics. pp. 92 et seqq. ISBN 978-99901-37-04-0. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ Khalifa, Haya Ali; Rice, Michael (1986). Bahrain through the ages: the archaeology. KPI. ISBN 978-0-7103-0112-3. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ Oxford Business Group (2007). The Report: Emerging Bahrain 2007. Oxford Business Group. pp. 158 et seqq. ISBN 978-1-902339-73-3. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- 1 2 Crawford, Harriet; Rice, Michael (1 December 2005). Traces of Paradise: The Archaeology of Bahrain, 2500 BC to 300 AD. I.B.Tauris. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-86064-742-0. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harriet E. W. Crawford (12 July 2000). Traces of paradise: the archaeology of Bahrain 2500 BC-300 AD : an exhibition at the Brunei Gallery, Thornhaugh Street, London WC1, 12 July-15 September 2000. I.B. Tauris. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-0-9538666-0-1. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

Further reading

- Kervran, Monik; Hiebert, Fredrik Talmage; Rougeulle, Axelle (2005). Qalʻat al-Bahrain: a trading and military outpost 3rd millennium B.C. – 17th century A.D. Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-99107-8.