Beniamino Gigli

| Beniamino Gigli | |

|---|---|

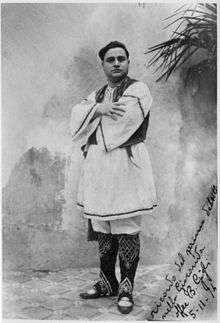

Beniamino Gigli in an image from 1914 | |

| Born | March 20, 1890 |

| Died | November 30, 1957 (aged 67) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Singer |

Beniamino Gigli (pronounced [benjaˈmiːno ˈdʒiʎʎi]; March 20, 1890 – November 30, 1957)[1] was an Italian opera singer. The most famous tenor of his generation, he was renowned internationally for the great beauty of his voice and the soundness of his vocal technique. Music critics sometimes took him to task, however, for what was perceived to be the over-emotionalism of his interpretations. Nevertheless, such was Gigli's talent, he is considered to be one of the very finest tenors in the recorded history of music.

Biography

Gigli was born in Recanati, in the Marche, the son of a shoemaker who loved opera. His parents did not, however, view music as a secure career.[2] Beniamino's brother Lorenzo became a famous Italian painter.[3]

In 1914, he won first prize in an international singing competition in Parma. His operatic debut came on October 15, 1914, when he played Enzo in Amilcare Ponchielli's La Gioconda in Rovigo, following which he was in great demand.

Gigli made many important debuts in quick succession, and always in Mefistofele: Teatro Massimo in Palermo (March 31, 1915), Teatro di San Carlo in Naples (December 26, 1915), Teatro Costanzi di Roma (December 26, 1916), La Scala, Milan (November 19, 1918), and finally the Metropolitan Opera, New York (November 26, 1920). Two other great Italian tenors present on the roster of Met singers during the 1920s also happened to be Gigli's chief contemporary rivals for tenor supremacy in the Italian repertory—namely, Giovanni Martinelli and Giacomo Lauri-Volpi.

Some of the roles with which Gigli became particularly associated during this period included Edgardo in Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini's La Bohème and the title role in Umberto Giordano's Andrea Chénier, both of which he would later record in full.

Gigli rose to true international prominence after the death of the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso in 1921. Such was his popularity with audiences he was often called "Caruso Secondo", though he much preferred to be known as "Gigli Primo." In fact, the comparison was not valid as Caruso had a bigger, darker, more heroic voice than Gigli's sizable yet honey-toned lyric instrument.

Gigli left the Met in 1932, ostensibly after refusing to take a pay cut. Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the Met's then general manager, was furious at his company's most popular male singer; he told the press that Gigli was the only singer not to accept the pay cut. There were in fact several others, Lily Pons and Rosa Ponselle among them; and it is well documented that Gatti-Casazza gave himself a large pay increase in 1931, so that after the pay cut in 1932 his salary remained the same as it had been originally. Furthermore, Gatti was careful to hide Gigli's counter offer from the press, in which the singer offered to sing five or six concerts gratis, which in dollars saved was worth more than Gatti's imposed pay cut.

After leaving the Met, Gigli returned again to Italy, and sang in houses there, elsewhere in Europe, and in South America. He was criticised for being a favourite singer of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, having recorded the Fascist anthem "Giovinezza" in 1937 (it is noticeably excluded from his "Edizione Integrale," released by EMI[4]). Toward the end of World War II, he was able to give few performances. However, he immediately returned to the stage when the war ended in 1945, and the audience acclaim was greater and more clamorous than ever.

In addition to his stage performances, Gigli appeared as an actor in over twenty films from 1935 to 1953. Some notable appearances include 1936's Johannes Riemann-directed musical drama Ave Maria opposite actress Käthe von Nagy and Giuseppe Fatigati's 1943 drama I Pagliacci (English release title: Laugh Pagliacci), opposite Italian actress Alida Valli.

In the last few years of his life, Gigli gave concert performances more often than he appeared on stage. Before his retirement in 1955, Gigli undertook an exhausting world tour of farewell concerts. This impaired his health in the two years that remained to him, during which time he helped prepare his memoirs (based primarily on an earlier memoir, fleshed out by a series of interviews). Gigli died in Rome in 1957.

Personal life

Like many artists, Gigli was a man of contradictions. On one hand, he gave more fund-raising concerts and raised more money than any other singer in history, with close to one thousand benefit concerts. He was deeply devoted to Padre Pio, his confessor, to whom he donated a large amount of money. Also, Gigli sang an unusual amount of sacred music (especially in the 1950s), atypical of a leading operatic tenor. Additionally, he was throughout his life deeply devoted to the sacred music of Don Lorenzo Perosi.

On the other hand, Gigli's relationships with women were often tainted by scandal. He lied in his memoirs, saying that he was married six months earlier than he really was. This was to conceal that his wife Costanza was pregnant before reaching the altar. Gigli had two children with Costanza: Enzo and Rina. (The latter was a well-known soprano in her own right.) Later, Gigli is well known to have had a second family with Lucia Vigarani, producing three children. Gigli is rumoured to have had at least three other children with as many different women. Gigli's exact number of offspring is unknown.

Legacy

Such is Gigli's popularity that most of his recordings, including complete operas with Maria Caniglia, Rina Gigli, Licia Albanese and Toti dal Monte, have been reissued on CD. His recorded legacy dates back to the 1920s and provides a good insight into the beauty of his voice.

Selected filmography

- Forget Me Not (1935)

- Forget Me Not (1936)

- Ave Maria (1936)

- Night Taxi (1950)

Biographies

- Marchand, Miguel Patrón (1996). Como un Rayo de Sol: El aureo legado de Beniamino Gigli.

- Brander, Torsten (2001). Beniamino Gigli: Il tenore di Recanati.

- Inzaghi, Luigi (2005). Beniamino Gigli. Varese: Zecchini Editore. p. 608.

References

- ↑ "Beniamino Gigli". Allmusic. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Beniamino Gigli: A Life in Music". Music Web - International. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ Gigli, Beniamino (1957). Memoirs.

- ↑ High fidelity. 1957. Records in Review. Wyeth Press. p. 360.

External links

- Opera Vivrà - Beniamino Gigli's biography

- International Jose Guillermo Carrillo Foundation

- Discography (Capon's Lists of Opera Recordings)

- History of the Tenor - Sound Clips and Narration