Blueberry (comics)

| Blueberry | |

|---|---|

|

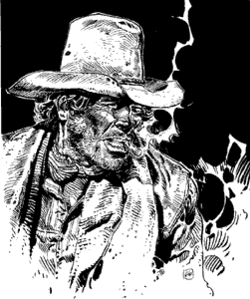

Blueberry as drawn by Jean Giraud | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Dargaud, Le Lombard, Fleurus, Hachette, Novedi, Alpen Publishers |

| Format | Graphic novel |

| Genre | Western |

| Publication date | 1963–2012 (Moebius' death) |

| Main character(s) | Mike S. Blueberry (born as Michael Steven Donovan) |

| Creative team | |

| Writer(s) |

Jean-Michel Charlier (1963-1990), Jean Giraud (1995-2012) |

| Artist(s) | Jean "Mœbius" Giraud |

| Creator(s) |

Jean-Michel Charlier Jean Giraud |

Blueberry is a Franco-Belgian comics western series created by the Belgian scriptwriter Jean-Michel Charlier and French comics artist Jean "Mœbius" Giraud. It chronicles the adventures of Mike Blueberry on his travels through the American Old West. Blueberry is an atypical western hero; he is not a wandering lawman who brings evil-doers to justice, nor a handsome cowboy who "rides into town, saves the ranch, becomes the new sheriff and marries the schoolmarm."[1] In any situation, he sees what he thinks needs doing, and he does it.

The series spawned out of the 1963 Fort Navajo comics series, originally intended as an ensemble narrative, but which quickly gravitated around the breakout character "Blueberry" as the main and central character after the first two stories, causing the series to continue under his name later on. The older stories, released under the Fort Navajo moniker, were ultimately reissued under the name Blueberry as well in later reprint runs. Two spin-offs series, La Jeunesse de Blueberry and Marshall Blueberry, were created pursuant the main series reaching its peak in popularity in the early 1980s.[2]

It has been remarked that during the 1960s, Blueberry "was as much a staple in French comics as, say, The Avengers or The Flash here [in the USA]."[3]

Synopsis

Born on 30 October 1843 on Redwood Plantation near Augusta, Georgia,[4] Michael Steven Donovan is the son of a rich Southern planter and starts out life as a decided racist. On the brink of the American Civil War, Donovan is forced to flee north after being framed for the murder of his fiancee Harriet Tucker's father, a plantation owner. On his flight toward the Kentucky border, he is saved by Long Sam, a fugitive African-American slave from his father's estate, who paid with his life for his act of altruism. Inspired when he sees a blueberry bush, Donnovan chooses the surname "Blueberry" as an alias when rescued from his Southern pursuers by a Union cavalry patrol (during his flight war had broken out between the States). After enlisting in the Union Army, he becomes an enemy of discrimination of all kinds, fighting against the Confederates (although being a Southerner himself, first enlisting as a bugler in order to avoid having to fire upon his former countrymen), later trying to protect the rights of Native Americans. He starts his adventures in the Far West as a lieutenant in the United States Cavalry shortly after the war. On his many travels in the West, Blueberry is frequently accompanied by his trusted companions, the hard-drinking deputy Jimmy McClure, and later also by "Red Neck" Wooley, a rugged pioneer and army scout.

Characters

Publication history

Original publications in French

In his youth, Giraud had been a passionate fan of American Westerns and Blueberry has its roots in his earlier Western-themed works such as the Frank et Jeremie shorts, which were drawn for Far West magazine when he was only 18 – also having been his first sales as free-lancer – , the Western short stories he created for the magazines from French publisher Fleurus (his first professional tenured employment as comic artist in the period 1956-1958), and his collaboration with Jijé on an episode of the latter's Jerry Spring series in 1961, which appeared in the Belgian comics magazine Spirou (fr:La Route de Coronado, issues 1192 - 1213, 1961), aside from his Western contributions to Jijé's own short-lived comic magazine Bonux-Boy (1960/61). After his involvement with Bonus-Boy, around 1961-1962, Jean Giraud approached Jean-Michel Charlier, asking him if he was interested in writing scripts for a new western series for publication in Pilote, the by Charlier recently co-established French comic magazine. Charlier refused at first, since he never felt much empathy for the genre. In 1963 the magazine sent Charlier on a reporting assignment to Edwards Airforce Base in the Mojave Desert, California. He took the opportunity to discover the American West, returning to France with a strong urge to write a western. First he asked Jijé to draw the series, but Jijé thought there would be a conflict of interest, since he was a regular artist at Spirou, a competing comic magazine, not to mention that he was very much invested in his own Jerry Spring western, quite popular at the time.[5] In his stead, Jijé proposed his protégé Giraud as the artist.[6] Charlier and Giraud have also collaborated on another Western strip, Jim Cutlass.

Blueberry was first published in the October 31, 1963 issue of Pilote magazine.[7] Initially titled "Fort Navajo", the story grew into 46 pages over the following issues. In this series Blueberry - whose physical appearance was inspired by French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo[8][9] - was only one of many protagonists; the series was originally intended to be an assemble narrative, but quickly gravitated towards Blueberry as the central and primary character, even though the series' (sub-)title "Fort Navajo, une Aventure du Lieutenant Blueberry" was maintained for a decade by original publisher Dargaud for the numerous reprint, and international, runs, before the "Fort Navajo" moniker was finally dropped in 1973 with the book publication of L'homme qui valait 500 000 $. Charlier came up with the name during his American trip: "When I was traveling throughout the West, I was accompanied by a fellow journalist who was just in love with blueberry jam, so much in love, in fact, that I had nicknamed him 'Blueberry'. When I began to create the new series, and everything started to fall into place, I decided to reuse my friend's nickname, because I liked it and thought it was funny. [...] I had no idea that he would prove so popular that he would eventually take over the entire series, and later we would be stuck with that silly name!"[5]

After Charlier had died in 1989, Giraud, aside from completing Arizona Love on his own, wrote and drew five albums, from Mister Blueberry to Dust, until his own death in 2012. Additionally, Giraud also scripted the intermezzo series Marshal Blueberry (1991-2000), but had no creative input for the Young Blueberry prequel series, after the first three, original volumes.

In post-war Europe, it has been tradition to release comics in "pre-publication" as serialized magazine episodes, before publication as a comic book, or rather comic album (in North-American understanding though, "graphic novel" is the more applicable terminology in this case, the distinction being a non-issue in native France), typically with a one to two year lag. In French, Blueberry has firstly seen pre-publication in Pilote and Super Pocket Pilote (1963 – 1973) from publisher Dargaud, the parent and main publisher of Blueberry, with Giraud frequently creating original Blueberry art for the magazine covers, aside from creating on occasion summarizing, introduction plates, none of which reprinted in the original book editions.[10] After Dargaud had lost publishing rights for over a decade for new Blueberry titles, as a result from a conflict with the creators over Blueberry royalties, the series has seen French pre-publication in such magazines as Nouveau Tintin,[11] Métal Hurlant,[12] Super As,[13] and Spirou,[14] Other European countries followed the same template with local magazines. However, the format, for decades a staple in Europe and shaping entire generations of comic readers, went out of vogue in the late 1980s/early 1990s and the vast majority of European comic magazines have since then become defunct by the mid 1990s, including those from Belgium, the country were the phenomenon was born in the late 1930s.[15] Le bout de la piste and Arizona Love, became the last serialized main series titles, though, ironically, neither were serialized in France itself, where La dernière carte had previously become the very last Blueberry title to be serialized in a magazine.[16] Henceforth, Blueberry titles were directly released in album format, starting with the 1990 Young Blueberry title, Le raid infernal.

Royalties conflict & Blueberry's publishing wanderings

With the growing popularity of Blueberry came the increasing disenchantment over financial remunerations of the series. Already in 1974, Charlier made his displeasure known in this regard, when he had Angel Face pre-published in Nouveau Tintin of industry competitor Le Lombard, the very first time a Blueberry adventure was not serialized in Pilote – nor would it ever be in hindsight. The magazine was forced to drop the announcement page it had prepared for the story.[17] Unfazed, Dargaud founder and owner fr:Georges Dargaud, unwilling to give in, reacted by having the book released before Nouveau Tintin had even had the chance to run the story. Then Giraud left on his own accord, to explore his "Mœbius" alter ego. While Charlier had no influence on this whatsoever, it did serve a purpose as far as he was concerned. Giraud had left Blueberry on a cliff-hanger with Angel Face, resulting in an insatiable demand for more, putting the pressure on Dargaud. Whenever Georges Dargaud asked Charlier for a next Blueberry adventure, repeatedly, Charlier was now able to respond that he was "devoid of inspiration".[18]

Five years later, Giraud was ready to return to Blueberry. Yet, the whole business surrounding Blueberry residuals had remained unresolved, and in order to drive home the point the pe-publication of the eagerly awaited Nez Cassé story was farmed out to Métal Hurlant magazine, instead of Pilote. Yet, Georges Dargaud refused to take the bait and the creators subsequently put forward the Jim Cutlass western comic as a final effort to show George Dargaud that the creators had options. Georges Dargaud still would not budge. It was then that it became clear to Charlier, that he was left with no other option than to leave, and this he did taking all his other co-creations with him, to wit Redbeard and Tanguy et Laverdure, which, while not as popular as Blueberry, were steady money making properties for Dargaud nonetheless.

Though they were still contractually obligated to leave their most recent Blueberry title, Nez Cassé, at Dargaud for book publication, Charlier and Giraud then threw in their lot with German publisher de:Koralle-Verlag – incidentally the first German language Blueberry book publisher back in the early 1970s – , a subsidiary at the time of German media giant Axel Springer SE, for their next publication, La longue marche. The choice for the German publisher was made for their very ambitious international expansion strategy they had in place at that time. Fully subscribing to the publisher's strategy, Charlier not only revitalized his Redbeard and Tanguy et Laverdure comic series, these having become somewhat dormant in the Pilote-era because of the royalties issue, but created new ones as well, most notably the western, Les Gringos. Yet for all Charlier's business acumen, he had failed to recognize that Koralle's exuberant expansion drive had essentially been a do-or-die effort on their part. In 1978 Koralle was on the verge of bankruptcy, and a scheme was devised to stave off this fate; international expansion. In the European comics world that was a rather novel idea at the time and Koralle did expand beyond the German border into large parts of Europe with variations of their main publication Zack magazine, accompanied with comic book releases. It did not pay off however, as the holding company pulled the plug in 1982, leaving Blueberry and the others quite unexpectedly without a publishing home.[19]

English translations

The first known English translation of Blueberry appeared 18 months after its original French magazine publication. The first outing in the series was serialized in syndication through Charlier's own EdiFrance/EdiPresse agency (the only Blueberry title known to have been disseminated in this manner outside French speaking Europe, Spain and Portugal[20]) under its original title in the British comic magazine Valiant, starting its black and white run from July 1965 onward, though "Fort Navajo" has until 1977 remained the only translated one.[21]

The first four English book translations of Blueberry comics were published in Europe for release in the UK in the late seventies by Danish/British joint venture Egmont/Methuen, when Egmont, holding an international license at the time, was in the process of releasing the series on a wider, international scale, for Germany and the Scandinavian countries in particular. While Egmont completed the publication of the then existing series in whole for the latter two language areas, publication of the English titles already ceased after volume 4. Parent publisher Dargaud had planned to reissue these titles and more for the North-American market in 1982/83 through their short-lived international (American) branch, but of these, only one was eventually released.[22] That then unnoticed title, The Man with the Silver Star, has, despite the fact that Giraud's art style had by now fully blossomed into his distinctive own, not been included in later North American collections, resulting in the book becoming an expensive rarity.

Since then better marketed English translations were published by several such other companies as Epic Comics, Comcat, Mojo Press and Dark Horse Comics, resulting in all kinds of formats and quality—from b/w, American comic book sized budget collections to full color European graphic novel style albums with many extras. Since 1993 no Blueberry comics have been published in English. Moebius created new covers especially for the Epic line of Blueberry. Actually this was the first time Blueberry was published under Giraud's pseudonym, Moebius. As R.J.M. Lofficier, the translator of the books wrote: "This is quite ironic because Giraud first coined the 'Moebius' pseudonym precisely because he wanted to keep his two bodies of work separate. Yet, the artist recognizes the fact that he has now become better known in this country under his 'nom-de-plume,' and this is his way of making it official!"[1]

The Epic publications were very shortly after their initial release collected by American specialty publisher Graphitti Designs in their "Moebius" collection, a deluxe limited edition anthology collection, released in a 1500 copies per volume edition, each volume at least containing two of the Epic releases. The collection, which ran for nine volumes, also contained Giraud's science fiction body of work, that was concurrently released by Epic in a similar manner. Volume Moebius #9, containing the "The Lost Dutchman's Mine" and "The Ghost with the Golden Bullets", also included the non-Blueberry westerns "King of the Buffalo" (short), and the other Giraud/Charlier western strip, Jim Cutlass: Mississippi River.

| # | French title (original magazine publication) | French original book release (publisher, yyyy/mm, ISBN)[23] | English saga title/French story cycle | English title and data | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fort Navajo (Pilote, issues 210-232, 1963) | Dargaud, 1965/09, n/a | Lieutenant Blueberry/Fort Navajo Series | Fort Navajo (Egmont/Methuen, 1977, ISBN 041605370X; Dargaud, 1983) | Printed in Belgium for the UK market. France printed Dargaud editions, intended for the USA and British Canada, were projected for 1982/83 but ultimately canceled. French Canada has traditionally been served with the original French publications. |

| 2 | Tonnerre à l'ouest (Pilote, issues 236-258, 1964) | Dargaud, 1966/01, n/a | Thunder in the West (Egmont/Methuen, 1977, ISBN 0416054307; Dargaud, 1982) | ||

| 3 | L'aigle solitaire (Pilote, issues 261-285, 1964) | Dargaud, 1967/01 n/a | Lone Eagle, (Egmont/Methuen, 1978, ISBN 0416050301; Dargaud, 1982) | ||

| 4 | Le cavalier perdu (Pilote, issues 288-311, 1965) | Dargaud, 1968/01, n/a | Mission to Mexico (Egmont/Methuen, 1978, ISBN 0416050409), The Lost Rider (Dargaud, 1983) | ||

| 5 | La piste des Navajos (Pilote, issues 313-335, 1965) | Dargaud, 1969/01, n/a | Trail of the Navajo (Dargaud, 1983) | canceled/not translated | |

| 6 | L'homme à l'étoile d'argent (Pilote, issues 337-360, 1966) | Dargaud, 1969/10, n/a | Lieutenant Blueberry/one-shot | The Man with the Silver Star (Dargaud, 1983/Q2, ISBN 2205065785) | Printed and published by the original publisher in France for the US and British Canadian markets, hence the French ISBN number as specified by French copyright laws; Of the six titles originally projected, the only one actually released. |

| 7 | Le cheval de fer (Pilote, issues 370-392, 1966) | Dargaud, 1970/01, n/a | Lieutenant Blueberry/Iron Horse series | The Iron Horse (Epic, 1991, ISBN 0871357402; Moebius #8, Graphitti Designs, 1991, ISBN 0936211350) | Graphitti Designs release erroneously carrying the same ISBN number as Volume 9 |

| 8 | L'homme au poing d'acier (Pilote, issues 397-419, 1967) | Dargaud, 1970/03, n/a | Steel Fingers (Epic, 1991, ISBN 0871357410; Moebius #8, Graphitti Designs, 1991) | ||

| 9 | La piste des Sioux (Pilote, issues 427-449, 1967) | Dargaud, 1971/01, n/a | General Golden Mane (Epic, 1991, ISBN 0871357429; Moebius #8, Graphitti Designs, 1991) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Trail of the Sioux" | |

| 10 | Général tête jaune (Pilote, issues 453-476, 1968) | Dargaud, 1971/10, n/a | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book title. | ||

| 11 | La mine de l'allemand perdu (Pilote, issues 497-519, 1969) | Dargaud, 1972/01, n/a | Marshall Blueberry/Goldmine series | The Lost Dutchman's Mine (Epic, 1991, ISBN 0871357437; Moebius #9, Graphitti Designs, 1991, ISBN 0936211350) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. |

| 12 | Le spectre aux balles d'or (Pilote, issues 532-557, 1970) | Dargaud, 1972/07, n/a | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Ghost with the Golden Bullets" | ||

| 13 | Chihuahua Pearl (Pilote, issues 566-588, 1970) | Dargaud, 1973/01, n/a | Blueberry/Confederate Gold series | Chihuahua Pearl (Epic, 1989, ISBN 0871355698; Moebius #4, Graphitti Designs, 1989, ISBN 0936211202; Titan Books, 1989, ISBN 1852861908) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. |

| 14 | L'homme qui valait 500 000 $ (Pilote, issues 605-627, 1971) | Dargaud, 1973/07, n/a | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Half-a-Million Dollar Man". The first time the Fort Navajo moniker has been dropped from the series (sub-)title by the French parent publisher. | ||

| 15 | Ballade pour un cercueil (Pilote, issues 647-679, 1972) | Dargaud, 1974/01, n/a | Ballad for a Coffin (Epic, 1989, ISBN 0871355701; Moebius #4, Graphitti Designs, 1989; Titan Books, 1989, ISBN 1852861916) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. | |

| 16 | Le hors-la-loi (Pilote, issues 700-720, 1973, as "L'outlaw"[24]) | Dargaud, 1974/10, n/a | Blueberry/Conspiracy series | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Outlaw" | |

| 17 | Angel Face (Nouveau Tintin, issues 1-9, 1975) | Dargaud, 1975/07, ISBN 2205009109 | Angel Face (Epic, 1989, ISBN 087135571X; Moebius #5, Graphitti Designs, 1990, ISBN 0936211210; Titan Books, 1990, ISBN 1852861924) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. | |

| 18 | Nez Cassé (Métal Hurlant, issues 38-40, 1979) | Dargaud, 1980/01, ISBN 2205016369 | Blueberry/Rehabilitation series | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "Broken Nose" | |

| 19 | La longue marche (Super As, issues 69-72, 85-87, 1980) | Fleurus/EDI-3-BD, 1980/10, ISBN 2215003650[25] | The Ghost Tribe (Epic, 1990, ISBN 0871355809; Moebius #5, Graphitti Designs, 1990; Titan Books, 1990, ISBN 1852861932) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Long March" | |

| 20 | La tribu fantôme (L’echo des savannes, issues 81-83, 1981) | Hachette/Novedi, 1982/03, ISBN 2010087356 | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. | ||

| 21 | La dernière carte (Spirou, issues 2380-2383, 1983) | Hachette/Novedi, 1983/11, ISBN 2010096835 | The End of the Trail (Epic, 1990, ISBN 0871355817; Moebius #5, Graphitti Designs, 1990; Titan Books, 1990, ISBN 1852861940) | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title: "The Last Card"

| |

| 22 | Le bout de la piste (n/a) | Novedi, 1986/09, ISBN 2803900343 | Two chapters in one book. Chapter title same as book. | ||

| 23 | A – Arizona Love (n/a) | Alpen, 1990/10, ISBN 2731607793 | Mister Blueberry/one-shot | Arizona Love (Dark Horse Comics, 1993) | Divided into sequels: Cheval Noir #46-50. Black and white, American current size comic book format. |

| B – Three Black Birds (n/a) | Stardom, 1995, n/a | The Blueberry Saga #1: The Confederate Gold (Mojo Press, 1996, ISBN 1885418086) | Chapter title: "Three Black Birds"; 14-page black and white short Arizona Love sequel, American current size comic book format. | ||

| 24 | Mister Blueberry (n/a) | Dargaud, 1995/11, ISBN 2205044605 | Mister Blueberry/OK Corral series | not translated | |

| 25 | Ombres sur Tombstone (n/a) | Dargaud, 1997/11, ISBN 2205046179 | not translated | ||

| 26 | Geronimo l'Apache (n/a) | Dargaud, 1999/10, ISBN 2205048732 | not translated | ||

| 27 | OK Corral (n/a) | Dargaud, 2003/09, ISBN 2205053388 | not translated | ||

| 28 | Dust (n/a) | Dargaud, 2005/03, ISBN 2205056425 | not translated | ||

| 29 | Apaches (n/a) | Dargaud, 2007/10, ISBN 9782205060799 | one-shot (Lieutenant Blueberry) | not translated | |

- The first French book title, Fort Navajo, originally appeared as the 17th (and last) volume of the La Collection Pilote series. Actually, this collection had been an initiative of Charlier himself in his function as publishing co-editor, and the 17 titles in the collection were in effect Dargaud's first comic book releases, and an influential release at that. In order to give these releases a more "mature" image, the books were from the start executed as hard cover editions. Favorably received and though not being the first, the hard cover format definitively became the norm in France where henceforth all comic books were executed in the format – becoming indeed generally accepted as a mature part of French culture[26] – , whereas the vast majority of the other European countries continued to employ the soft cover format for decades to come, somewhat reflecting the status comic books had in their societies. That included for the time being French-Belgium as well, Charlier's native country, where exactly the same collection was also released by Le Lombard, albeit as soft cover only. Charlier's initiative was not entirely devoid of a healthy dose of self-interest, as over half the releases in the collection, were, aside from Blueberry, titles from other comic series he had co-created.

- The failure to publish La piste des Navajos in the English language, frustratingly left English readers with a cliffhanger, as it was the resolution of a five volume story line that started with Fort Navajo. As of 2016, only foreign language editions are available to them.

- In the case of Epic's Chihuahua Pearl, Ballad for a Coffin, Angel Face, The Ghost Tribe, and The End of the Trail book releases, Titan Books has issued the same, virtually identical books (save for the ISBN numbers and publisher's logo) for the UK market, with a few months delay. The other Epic Blueberry titles only saw an US release, the Titan editions thereby becoming the last British Blueberry publications. These editions were released in a relatively modest print run of 6.000 copies per title, as Giraud himself has divulged, though he has added, "Mind you, British readers were delighted; As a matter of fact, they adore [continental] European comics , which makes us proud over here [France]...".[27]

- As the title already suggested, The Lost Dutchman's Mine[28] was a take on the real world "Lost Dutchman's Gold Mine legend", and in the original publications the Lückner and "Posit" characters were from Prussia as specifically intended by Charlier, and as indicated by the "Allemand" (French for "German") reference in the French book title, therefore adhering to the actual legend in this respect. Translator Lofficier chose the for Americans familiar-sounding name of the real legend as title for the American book release, but changed the characters to being denizens from the Netherlands, in the process changing the original expletives from German to Dutch in his translations, aside from altering the Germanic name spellings accordingly. Though Lofficier, married to an US citizen, had worked for decades in the US in the publishing world, acquiring an excellent knowledge of American English and idiom, he had made a mistake when he interpreted the moniker "Dutch" as currently understood, too literally – as in from/of the Netherlands. Being of French descent, Lofficier had not realized that in the United States of the mid-to-late 19th century, the expression "Dutch" has had a different meaning (Charlier, who was aware of this, had by that time already passed away, and thus unable to set Lofficier straight), as it was by Americans invariably employed to refer to people and language of German descent/origin, due to the massive influx of German speaking immigrants in that period of time. These immigrants referred to themselves as "Deutch" in their own language, and the phonetic similarity is the more commonly accepted rationale for the phenomenon. Remarkably, the phenomenon has not applied for Canada.[29]

- Mojo Press published a black and white, American comic book sized budget collection: The Blueberry Saga #1: The Confederate Gold in 1996. It contains the following stories: "Chihuahua Pearl", "The Half-A-Million Dollar Man", "Ballad for a Coffin", "The Outlaw", "Angel Face". It also featured the first-time book publication worldwide of the 14-page Blueberry short, "Three Black Birds" – the year previously released under the same title as a limited edition, 28-sheet mini portfolio by Stardom, Giraud's own publishing house[30] – , which was actually set directly after the events depicted in Arizona Love, though that title was not included in the anthology. As the title already implied, the book was coined after the actual, so-called "Confederate gold myth".

- The 2007 one-shot Apaches is an edited book collecting the flashback recollections Blueberry related from Ombres sur Tombstone through Dust to a journalist while convalescing from a gunshot wound he had sustained in the preceding story, detailing how he, after the war and suffering from a severe case of post traumatic stress syndrome, arrives in the South West in late autumn 1865, and his subsequent dealings with Apache warrior Goyaałé, before the latter came to national attention as Geronimo. There it was revealed that it had been Geronimo who had given Blueberry his Native-American nickname "Tsi-Na-Pah" ("Broken Nose"[31]). For the book Giraud created new pages and panels to improve the flow of the story, and as such the book is readable as a stand-alone prequel title. Notable are the new, last two pages which shows Blueberry leaving his very first Far West posting, while wearing the outfit, he is first seen in, in "Fort Navajo", his second posting, providing a seamless continuity (even though Giraud had made a continuity error as one of the panels featured a with the year 1881 engraved tombstone, the year in which the "Mister Blueberry" story cycle, centered around the historical "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" incident, was set). While the French themselves consider the book outside the main series, due to the prequel nature of the book, it is otherwise universally considered part of the main series in other countries.

- After Blueberry's rehabilitation in Le bout de la piste, Charlier had planned to have him return to the US Army as captain, heading a unit of Apache Scouts.[32] However, after Charlier's death, Giraud became of different mind when he embarked on the Mister Blueberry story cycle, turning the hero in to a loafing civilian, because of his new-found wealth and spending his days with poker, as he felt that it would have been too illogical and too implausible for Blueberry to return to the very same organization that had caused him so much grief and injustice.[33]

- There is a chronology gap of eight years between Arizona Love and Mister Blueberry, which was specifically intended by Giraud, "Mister Blueberry takes place eight years later, which leaves room for further romantic speculations. Surely, many readers will ask themselves, what Blueberry has been up to in the intervening time."[34] Yet, what the creators had overlooked however, was that they had made a continuity error, by placing the events in Arizona Love in 1889 in the opening panel, whereas Giraud clearly had meant 1873, amply demonstrated by him correcting the year in "Three black Birds".

Non-English translations

Since its inception, the series has slowly gained a large following in Europe, and has, in part or in whole, been extensively translated in both serialized and book versions into multiple languages, to wit, Spanish (both Spain proper and the Americas),[35] Portuguese (including Brasil),[36] Italian,[37] German,[38] Dutch,[39] Swedish,[40] Danish,[41] Norwegian,[42] Polish,[43] Finnish,[44] Serbo-Croatian,[45] Hungarian,[46] Greek,[47] Icelandic,[48] Turkish,[49] Tamil, Indonesian[50] and, more recently, Japanese. In Spanish and Portuguese Blueberry has seen (licensed) publications by local publishers in the Americas,[51] as it has in the former Yugoslavia after it disintegration into its constituent parts.[52] In the European Union, in case of trans-border language areas, it is customary to have publishing rights reside with one publisher only.

It should be noted that the fact that Charlier had chosen to disseminate Fort Navajo outside the French, Spanish and Portuguese language areas in magazine syndication, has caused problems for publishers in other language countries, especially in Germany and north-west Europe, when Blueberry broke out in popularity in the late 1960s, early 1970s, well before the syndication term was to expire in 1974. Since Fort Navajo was the first part of a longer story line, this caused continuity, or rather chronology problems as publishers were not yet able to publish the book in their countries. The respective publishers all went about the conundrum in their own way; in Germany the book was first re-serialized as a magazine publication,[53] before continuing with the book releases of the subsequent titles; in the Netherlands and Flanders it was decided to push ahead with book publication regardless of Fort Navajo,[54] and in the Scandinavian countries it was decided to forego on the publication of the first five titles altogether, instead opting to start book publication with book six, L'homme à l'étoile d'argent,[55] leaving publication of the first five titles for a future point in time. No matter what solution was chosen, it became one of the reasons for the messed up book release chronologies for those countries (only aggravated by the later addition of Young Blueberry book titles), confusing readership, especially in Germany.[56] It was Finnish publisher Sanoma that became the first publisher able to release the first other language book edition of the title in 1974, directly after the syndication term had expired, as Navaho: Väijytys Punaisessa laaksossa (OCLC 57920924), that country's very first Blueberry book publication, thereby avoiding the conundrum.[57] Nor had the conundrum been an issue for the UK, as book publication only started in 1977.

In the United States, California based distributor Public Square Books (currently known as Zócalo Public Square) imported Blueberry books from Spanish publisher Norma Editorial, S.A. on behalf of the Spanish speaking part of the country. Having done so in the first half of the 2000s, these books were endowed with American ISBN numbers in the form of a bar code sticker, simply put over the Spanish ISBN number. For example, Arizona Love originally carried the Spanish ISBN 8484314103, but once imported in the US, received the new, American ISBN 1594970831. Latino-Americans therefore, have been afforded the opportunity to enjoy the then entirety of the Blueberry series (including the spin-offs), contrary to their English speaking counterparts.

Apart from Europe, the Americas, Japan and Indonesia, the series has been translated on the Indian subcontinent in Mizo by Mahlua of Cydit Communications, operating out of Aizawl, and in Tamil. It is in the latter language in particular, spoken in the south-eastern part of India, Tamil Nadu, and on the island state of Sri Lanka, that the Blueberry saga has amassed a large fanbase and where he is dubbed "Captain Tiger" (கேப்டன் டைகர்). The series has been published by Prakash Publishers under their own "Lion Muthu Comics" imprint. In April 2015, an exclusive collectors edition was published in Tamil, collecting Blueberry titles 13 through 22 – with "Arizona Love" added in first time Tamil translation – in one 540-paged book. This is considered to be a milestone release in the entire Indian comics history, as well as one of the biggest collector editions of Blueberry comics worldwide,[58] although it had already been surpassed by the time of its release by an even more massive, single book anthology of 1456 pages by parent publisher Dargaud in the original language, the year previously.[59]

Prequel, intermezzo, and sequel

A "prequel" series, La Jeunesse de Blueberry (Young Blueberry), and the "intermezzo" series Marshal Blueberry have been published as well, with other artists and writers, most famously William Vance for the latter.

Young Blueberry (La Jeunesse de Blueberry)

A later created prequel series, dealt with Blueberry's early years, during the American Civil War, relating how the racist son of a wealthy plantation owner turned into a Yankee bugler and all the adventures after that. The material for the first three albums, conceived by the original Blueberry creators, were first seen in digest size Super Pocket Pilote during the late sixties as in total nine 16-page short stories, eight of them constituting one story-arc set in the war. The very first short story, "Thunder on the Sierra", was actually a post-war stand-alone adventure set before the events depicted in The Lost Dutchman's Mine. With the exception of the very first and very last, "Double Cross", all other shorts were originally published in black and white. Later these were blown up, rearranged, (re-)colored with some panels omitted in the process to fit the then standard album format of 46 pages (discounting the two disclaimer pages). The 1990 English language edition of these stories, by Catalan Communications under their "ComCat" line, gave track of the changes and presented the left out panels in editorials in which Giraud himself presented clarifications for the choices made. Only these first three books were published in English. The three American albums were also, unaltered and unedited, included in the aforementioned anthology collection from Graphitti Designs.

| # | French original book release (publisher, yyyy/mm, ISBN)[23] | French chapter titles (original order and magazine publication) | English saga title/French story-arc | English title and data | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | La jeunesse de Blueberry (Dargaud, 1975/01, ISBN 2205007785) |

|

Young Blueberry | Blueberry's Secret (ComCat comics, September 1989, ISBN 0874160685; Moebius #6, Graphitti Designs, 1990, ISBN 0936211229) | Three chapters in one book. Chapter titles:

|

| |||||

| 2 | Un Yankee nommé Blueberry (Dargaud, 1979/01, ISBN 2205014854) |

|

A Yankee Named Blueberry (ComCat comics, March 1990, ISBN 0874160871; Moebius #6, Graphitti Designs, 1990) | Three chapters in one book. Chapter titles:

| |

| |||||

| 3 | Cavalier bleu (Dargaud, 1979/10, ISBN 2205014854) | Chapter titles:

|

The Blue Coats (ComCat comics, July 1990, ISBN 0874160936; Moebius #6, Graphitti Designs, 1990) | Three chapters in one book. Chapter titles:

| |

|

one-shot (Lieutenant Blueberry) |

| |||

|

- The publication of La jeunesse de Blueberry in 1975 came as a surprise to Blueberry fans. Having left Blueberry on a cliffhanger with Angel Face, when Giraud took his extended leave of absence (see below), clamor for new Blueberry titles became such, that publisher Dargaud decided to make the move as a temporary stop-gap solution.

- While the removal of individual panels was regrettable from a graphics point of view, it entailed no consequences for the plot lines of the shorts, save one; in "Blueberry's Secret" the in the synopsis mentioned Long Sam had witnessed the murder Blueberry was accused of and therefore able to prove his innocence, but is gunned down before he is able to do so by the real murderer, who in turn is gunned down by Blueberry, leaving Blueberry without any recourse to prove his innocence. However, for the book publication, the two panels which showed the real murderer being killed were cut, causing a discrepancy as it left readers wondering why Blueberry was so despondent, as, from their point of view, the real killer was still alive. Unlike European readers,[60] American readers were afforded a clarification for the discrepancy in the editorial of the ComCat release.

- The releases of the two follow-up titles four years later (in itself an indication that Dargaud had not planned to do so initially, if only for the substantial editorial effort it took in the pre-computer era to adapt the original digest size for the standard sized comic book), turned out to be in equal measure a stop-gap initiative. Unable to resolve the royalties conflict, which had dragged on for five years, Charlier and Giraud turned their back on the parent publisher, leaving for greener pastures elsewhere and taking all of Charlier's co-creations with them. Sensing that it might potentially turn out to be a costly defection, the two Young Blueberry titles were released to make the most of the fervor that had surrounded the return of Blueberry. For Dargaud it indeed turned out to be a costly affair as the three 1979/80 titles were the last new titles they were able to release for nearly fifteen years, missing out on a period of time in which Blueberry reached the pinnacle of its popularity – seeing, besides new titles in the main series, the birth of two spin-off series as well – , even though the publishing rights of the older book titles remained where they were.

- In their haste to release the two followup titles, in the process also having to pay "renegade" Giraud for his input, the editorial office of Dargaud made a substantial editorial blunder. As stated, eight of the nine shorts constituted one long story-arc, but Dargaud placed Chasse à l'homme (Manhunt, the fifth short in the story line) as the penultimate one in book 3, causing an awful continuity error. Readers, not familiar with the original Super Pocket Pilote publications, found themselves facing a baffling and inexplicable plot twist, only aggravated by the publisher who in unconvincing and confusing text captions tried to explain the discrepancy away, leaving uninitiated fans at the time erroneously suspecting that not all shorts were being published. In the publisher's defense however, it should be noted that Charlier had confusingly, but unintentionally, given two of his shorts an identical title in French and it is not that much a stretch of the imagination to assume the editors believing that the two stories belonged with each other. Fortunately for the American readership, the correct chronology, pursuant a first correction in a Danish Anthology earlier that year,[61] was adhered to in the ComCat releases. Ironically, the French themselves, as indeed the rest of Europe, had to wait until 1995 (the Dutch actually beating the French to the punch by one year[62]) before the publisher, pursuant regaining the Blueberry rights, could be bothered to correct the chronology for later reprint runs, after having it allowed to persevere for nearly two decades in numerous prior reprint runs for all language editions, the Danish and American editions excepted.

- On a positive note, due to the fact that the "Thunder on the Sierra" short numbered 14 pages instead of 16, no editorial cutting was necessary for the third book.

- Aside from the editorial changes to fit the book format, Giraud made use of the opportunity to recreate a small number of panels to replace those he had felt unhappy about in hindsight. Again, it were American readers who were afforded his reasoning for this first, in the editorials of the ComCat releases.

- "Uncut" anthologies have since then been published published in Germany, Denmark and Norway by publisher Egmont and its German subsidiary Ehapa, as Volume 1[63] of their massive 2006-2011 Blueberry collection project, an international effort collecting all Blueberry series in one integral, multi-volume anthology collection for simultaneous release in these countries.[64] As of 2016 these releases stand out as the most compressive Blueberry release ever attempted, easily surpassing in scope similar efforts of parent publisher Dargaud.[65] Stand-alone uncut anthologies of the shorts, typically in black and white as use was made of the original Super Pocket Pilote source material instead of the book versions, have previously been published in Denmark (the above-mentioned 1990 edition), Germany and Croatia, albeit it an illegal one in the latter case.[66] None have seen the day of light to date in the rest of the world, including home country France.[67]

Change of artist

After Angel Face was completed in 1974, Giraud took an extended leave of absence from Blueberry, partly because he was tired of the publication pressure he was under in order to produce the series, partly because of the royalties conflict, but mostly because he wanted further explore and develop his "Moebius" alter ego, the work he produced as such being published in the by him co-founded Métal Hurlant magazine (in the US published as Heavy Metal), in the process revolutionizing the Franco-Belgian comic world. Having ended Angel Face on a cliffhanger, Giraud's return to Blueberry five years later with Broken Nose became a media event of considerable proportions and demand for Blueberry reached an all-time high. It was then that the creators decided to revisit the Young Blueberry adventures as well, which had ended its run in Super Pocket Pilote. However, Giraud was nowhere near able to take on yet another major series himself, as he was still working on his acclaimed Incal series as Moebius, besides having embarked on Blueberry again. There actually had been an additional, more prosaic reason as well for the decision to do so. After Giraud had finished Le bout de la piste he was preparing to leave for Tahiti. Having been very much invested throughout most of his adult life in New Age beliefs and practices (which included the use of mind-expanding substances[68]), Giraud planned to join the commune of mystic Jean-Paul Appel-Guéry – in effect doing so eventually for nearly three years – , the latter had set up on Tahiti. Publisher Novedi feared, not entirely unjustified, that it endangered the publication regularity of the main series, and resurrecting, or more accurately, creating the Young Blueberry series, was the back-up strategy they had in mind.[69] It was then that fate intervened, when Giraud, before his departure discovered the work of the still unknown ex-pat Colin Wilson from New Zealand, who was publishing a science fiction comic, Dans l'Ombre du Soleil for the French Circus comic magazine, which featured a character that shared a stunning resemblance with Blueberry. Wilson, who actually was a huge Giraud fan himself, was approached, and after a short apprenticeship to fine tune his art style (Wilson did part of the inking of Le bout de la piste, while his girlfriend fr:Janet Gale, who had followed him from New Zealand, took on the coloring, as indeed she would for all her future husband's Blueberry books), already close to that of Giraud, in order to have it move even closer to that of Giraud, embarked with fervor on the project with his first outing Missouri Demons, which essentially became the rationale for the Young Blueberry adventures to become a spin-off series onto their own.[69]

The Young Blueberry books were until 1990 considered part of the main series by parent publisher Dargaud, the first three from the original creators in particular, before they were instituted as a separate spin-off series, mostly for the practical reason of wanting to avoid further pollution of release numbering and chronology, Wilson's Le raid infernal becoming the first released as such, as indicated on its back cover. It was not Dargaud who took the initiative for the move, but rather publisher Novedi, due to the fact that Dargaud had lost the publishing rights for new Blueberry titles, actually missing out on the first five, most successful, titles of the new series as explained. But Dargaud did adopt the format, once these rights had returned to them in late 1993. Catalan Communications had planned to publish Missouri Demons and Terror over Kansas in their "ComCat" line as well, as indicated on the back covers of the ones published, Missouri Demons actually having already received an ISBN number. Publication came to naught however, due to the demise of the publishing house in early 1991.

While several European countries (including somewhat unconventional outliers Iceland and Turkey[70]) had, no post-original creators title has seen serialized magazine pre-publication in France/French-Belgium itself, where the titles were instead directly released as books. By the time the 1990 Le raid infernal was released however, virtually every other country had followed suit due to the demise of the serialized magazine format.[15]

Jean-Michel Charlier and Colin Wilson

- 4: Les démons du Missouri (Novedi, 1985/09, ISBN 2803900262)—Missouri Demons (ComCat comics, January 1991, ISBN 0874161096; canceled)

- 5: Terreur sur le Kansas (Novedi, 1987/10, ISBN 2803900467)—Terror Over Kansas (ComCat comics, 1991, canceled)

- 6: Le raid infernal (Novedi, 1990/03, ISBN 2803900645)

Change of writer

François Corteggiani and Colin Wilson

- 7: La pousuite impitoyable (Novedi, 1992/01, ISBN 2803900734)

- 8: Trois hommes pour Atlanta (Alpen Publishers, 1993/06, OCLC 413528824)

- 9: Le prix du sang (Dargaud, 1994/10, ISBN 2205042823)

Second change of artist

François Corteggiani and Michel Blanc-Dumont

- 10: La solution Pinkerton (1998)

- 11: La piste des maudits (2000)

- 12: Dernier train pour Washington (2001)

- 13: Il faut tuer Lincoln (2003)

- 14: Le boucher de Cincinnati (2005)

- 15: La sirene de Vera-Cruz (2006)

- 16: 100 dollars pour mourir (2007)

- 17: Le Sentier des larmes (2008)

- 18: 1276 âmes (2009)

- 19: Redemption (2010)

- 20: Gettysburg (2012)

- 21: Le convoi des bannis (2015)

No UK editions have seen the day of light as of 2016, but, like the source series, the Young Blueberry spin-off series did see translations in numerous languages, the three titles by the original creators and the Wilson outings specifically, but appreciatively less so for the subsequent releases. The latter is amply exemplified by the Corteggiani/Blanc-Dumont versions, which are not that favorably received – unlike the Wilson versions, whose first three outings were notably well received, in no small part due to the fact that they were still being written by co-creator Charlier – as indicated by its diminishing popularity; had volume 12 still seen a first-print run of 100.000 copies in France in 2001, by 2015 that number had dwindled to 40.000 (which in France is near the cut-off point for a standard comic book being economically viable to become published) when volume 21 was released,[71] aside from the fact that several publishers had foregone the publication of these book titles in their countries altogether. Currently, the spin-off series by Corteggiani and Blanc-Dumont only remains translated in Spanish, German, Dutch and Italian,[72] a far cry from the nearly two dozen languages the main series had once been published in.

Marshal Blueberry

"When fr:Guy Vidal from Humanos brought me into contact with Jean Giraud at the time, he presented me with a story that I liked very much. But Giraud had written the script as a novel. The page division was still lacking, as were the dialogs. Furthermore he had planned to spread the story over two books. I suggested to expand that to three books. After I had finished the first Marshal Blueberry, I did not want to do all the work alone anymore. I did not have the time, nor did I want to do the work, others should have rightfully done. Thierry Smolderen subsequently worked out the script. But then I procrastinated. Dargaud had bought back Blueberry, Giraud had rejected part of Smolderen's script, altered the page divisions, etcetera. In the end I became fed up with the third book, and threw in the towel."

—Vance, on his experiences working on Marshal Blueberry.[73]

This spin-off series was the second attempt to further capitalize on the huge popularity the main Blueberry series enjoyed at the time. Written by co-creator Giraud, the series was set around the events depicted in The Lost Dutchman's Mine and dealt with scrupulous gun runners arming Apaches, thereby instigating an uprising. Chosen for the art work was William Vance, an accomplished Belgian comic artist in his own right and renowned for his XIII comic series. Vance drew the first two outings in the series, but declined afterwards to continue, partly because he was required to finish an album in only four months (in Europe, one year was the typical mean to complete a comic book of 48 pages, but not rarely exceeds this time span in recent decades) and that he was unaccustomed to Giraud's style as scenario writer. Additionally, even though the first book sold 100.000 copies (while respectable, relatively modest compared to the contemporary print runs of the main series, they being printed in numbers at the very least double that[74]), fans received the book with mixed feelings as Vance's style was a too radical departure to their tastes from that of Giraud.[75] This actually was part of the reasons why Wilson's work was so favorably received and partly the reason why Blanc-Dumont's was not. The unresolved story cycle lingered in limbo for seven years, before fr:Michel Rouge – whose style was closer to that of Giraud – was found willing to finish the cycle.[76]

That Rouge's style resembled that of Giraud, was hardly a surprise, as Rouge was actually not a stranger to Blueberry. Twenty years earlier, when Rouge was still a quite unknown and aspiring comic artist, Giraud took him on as an apprentice and had him ink pages 15–35 of La longue marche in 1980 – thereby doing for an aspiring artist what Jijé had done for him nearly two decades before that. At the time it gave rise to the rumor that Giraud was planning to abandon his co-creation and that Rouge was groomed to take over the series. Though a rumor, there was a nuanced morsel of truth in it, as Rouge clarified two decades later, "No, he did not want to abandon Blueberry, but rather sought support and perhaps the opportunity to create books, like the ones he is currently doing [Mister Blueberry]. At the time, he was already playing with the notion of doing parallel series."[77]

Originally intended to become a full-fledged series, the three Marshal Blueberry titles have remained the only outings in the series, though they too have seen several foreign language publications. Although not in France itself, several European countries have seen serialized magazine pre-publication of the first two titles. The third 2000 title though, was invariably directly released in book format for virtually all countries.[15] No English language editions were released. Incidentally, in 2013 Giraud returned the favor Vance had provided for his co-creation, when he took on the art work of volume 17 for his XIII series, and which has seen English translations.

Jean Giraud and William Vance, page layout by René Follet

- 1: Sur ordre de Washington (Alpen Publishers, 1991/11, ISBN 2731609885)

- 2: Mission Sherman (Alpen Publishers, 1993/06, OCLC 801093625)

Jean Giraud and Michel Rouge

- 3: Frontière sanglante (Dargaud, 2000/06, ISBN 2205042777)

Blueberry 1900

"In it, Blueberry is 57 years old, the same age I am now, and he lives with the Hopi Indians. It is a kind of a merging between Moebius and Giraud, as it concerns a story about sorcerers and sjamans, quite out of this world."

"The story involves the assassination attempt on President McKinley. Neither Jimmy McClure nor Red Neck will appear in it. Additionally, I had the following for Blueberry 1900 in mind: President McKinley is lying in a coma and starts to levitate. Subsequently, they tie him to the bed so he does not float off, but then the whole bed starts to levitate. So now they have to nail down the whole bed. Blueberry 1900 – it has its origins in a smart dream, I have dreamt in the Pyrenees in 1981."

—Giraud, on his thoughts and intents for Blueberry 1900 in several comments made for contemporary magazine interviews.[78]

A third spin-off series, tentatively coined Blueberry 1900, was conceived by original creator Giraud in the mid-1990s, intended as a bonafide sequel series. Set, as the series title already implied, in the era of the William McKinley presidency, it would not only have featured a 57-year old Blueberry, but his adult son as well, albeit in a minor role. The story line, intended to encompass five books, was to take place around events surrounding the assassination of President McKinley. Pegged for the artwork was French comic artist François Boucq whom Giraud had met at a comic event, and concurrently discussed the project with. Boucq showed interest and was enthusiastic about the project, and indeed embarked on the production of pre-publication studies, but deemed a cycle of five books too much, managing to negotiate it down to a cycle of three books.[79]

However, Philippe Charlier, son of the late Jean-Michel Charlier and proprietor of "Editions JMC" – a foundation set up with the specific intent to safeguard the creative integrity and legacy of his father, both in a spiritual as well as a commercial sense – , was nowhere near as enthusiastic as Boucq was. He became increasingly alarmed and downright aghast when reading commentaries, Giraud made in contemporary magazine interviews, clarifying his intentions and premises for the proposed series of a Blueberry residing with the Hopi tribe, meditating under the influence of mind-expanding substances,[68] while President McKinley was levitating in the White House due to a Hopi spell. As heir and steward of his father's co-creations and legacy, being the 50% co-owner of Blueberry, he still had the unequivocal right to veto any and all proposals regarding Blueberry and did not hesitate for a moment to exercise his prerogative in this case, going as far as taking Giraud to court, resulting in that the project fell through. As per a horrified Charlier Jr. in a later statement, "The scenario is unbelievably horrifying. It is an effrontery, constructed out of implausible circumstances. Like in the new [Mister Blueberry] story cycle, we find a totally passive Blueberry, only meditating, while the president, enchanted by Indians, is levitating in the White House". As he indicated, though he had given his seal of approval in this case, Charlier Jr., also became wary and disapproving of Giraud depicting the former lieutenant as a passive loafer in the Mister Blueberry story cycle, only aggravated from his point of view by the fact that Giraud could not refrain himself from including some elements from Native-American mysticism in OK Corral and Dust – though not anywhere near as extensive as he had intended for Blueberry 1900.[80]

Philippe Charlier, conservative by nature like his father, had, unlike his father, no patience whatsoever with Giraud's "New Age" predilections, particularly for his admitted fondness for mind-expanding substances, subsequently vetoing his proposals for a "Fort Mescalero" one-shot, which was to feature extensive substance-induced hallucinatory scenes, besides Giraud's intention to have the Jim Cutlass series merge with the Blueberry main series, due to the fact that later volumes of that series also increasingly incorporated likewise scenes.[18] How far Giraud actually already was in his thinking was exemplified by the inclusion of his art featuring Blueberry with Hopi tribesmen, endowed with the caption "In Hopi Towns",[81] as the interior flyleaf illustration for the regular 1990 Arizona Love French book release,[82] reprinted as such, without the caption, in the last 1991 Graphitti Designs release, Moebius #9.

Boucq was disappointed with the project falling through, but for him it turned out to be a blessing in disguise as it became an inspiration for Alejandro Jodorowsky (co-creator of Giraud's acclaimed Incal series, and already a frequent Boucq collaborator), to co-create with him their own acclaimed western comic. fr:Bouncer. And even the fictional "Fort Mescalero" has resurfaced as Blueberry's very first Far West posting in the 2007 prequel book Apaches. As a warming-up for Blueberry 1900, Boucq and Giraud had already collaborated on a Native-American themed project when they both contributed to the 1995 "Laissé Pour Mort", a to 500 pieces limited CD/Portfolio release from Parisian-based publisher Stardom, Giraud's own publishing house/art gallery, ran at the time by his second wife Isabelle. Later, in 2008, Giraud submitted a "Blueberry-meets-Bouncer" contribution to the to 250 pieces limited "Bouncer" portfolio from short-lived publisher Osidarta, aside from providing a foreword.[83]

The Blueberry biography

"Blueberry can not die, I have the certainty and proof of that ever since I have read the biography, Charlier has written before he left us. He is such a rich character that people can not imagine him disappearing. According to Jean-Michel, Blueberry has even rubbed shoulders with Eliot Ness. The history of such a character can not have an ending."

"With that biography, we encumbered ourselves with a mind-boggling task. We had created the possibility to highlight Blueberry in a panoramic manner by concurrently publish several different series, in which he is young, less young and, why not, old eventually. We even could have told the story of his death without ending the series. Blueberry is a particularly intimate life companion. He is part of me, but it should not become an obsession. That is the reason why I have given him the chance to escape me by entrusting him to others. In essence, it has become Blueberry's fate to be condemned to life by his creators."

—Giraud, on his firm conviction that, due to the biography, Blueberry is now for the ages, and how it has allowed the Blueberry universe to expand beyond the boundaries of the main series.[84]

In 1974 Charlier had a sixteen-page background article added to Ballade pour un cercueil (OCLC 893750651), when the book was first released. The article concerned a fictitious biography of Mike Steve Donovan, alias Mike S. Blueberry, detailing his life from birth to death, and written from a historic, journalistic point of view. When asked about it a decade later, Charlier clarified that once it became clear to him that Blueberry had become the central character of the series he had conceived, he then already postulated in his mind the broad strokes of the complete life and works of his creation, including the reasons for Blueberry's broken nose and odd alias. By the time Ballade pour un cercueil was ready for its book release, Charlier deemed the moment had arrived to entrust his musings to paper. There had been a practical reason as well for this. The story already ran 16 pages over-length and as contemporary printers printed eight double-sided comic book pages on one sheet of print paper, the addition of the 16-page biography was not that much of a bother for their production process.[85] Ballade pour un cercueil therefore became one of the first Franco-Belgium comic albums to break the mold of the hitherto standard 48-page count format.

Currently somewhat of a staple in European comics, at that time the inclusion of an informative background section in a comic book of that size and wealth of detail was hitherto unheard of and a complete novelty, and what Charlier had not foreseen was that many in the pre-internet era mistook the biography for real, factual history, propagating it as such in other outside media as well.[86] Charlier, who also was an investigative journalist and a documentary maker with a solid reputation for thorough documentation, had previously already written several, shorter historical Old West background editorials for Super Pocket Pilote as companion pieces for the Young Blueberry shorts, which were historically accurate, and readers therefore assumed that the biography was likewise.

Still, having written the biography within the historical context as postulated in the comic, fully expecting his readership to understand it as such, Charlier has never had the intention to perform a prank at the expense of his readers. "I have written a fictitious biography on Blueberry, accompanied by photographs found in American archives, and the whole world went for it!", declared a somewhat baffled Charlier,[87] having already stated on a previous occasion, "To this very day, because of Ballade pour un cercueil in which we gave Blueberry a with photographs illuminated biography, I still receive letters from readers – not from kids mind you, but from grownups – asking how on Earth we have managed to track down the real Blueberry. There are people who take it for real fact."[88] The photos were indeed authentic, though their captions were not. To complete the appearance of a bonafide in-universe biography, a Civil War-era style group portrait, featuring Blueberry, was included, ostentatiously recently discovered and from the hand of American artist Peter Glay, but in reality created by Pierre Tabary, a French book illustrator of some renown at the time.[89] Incidentally, a salient detail was that events, as related in the biography, in Blueberry's life directly upon war's end, but before he arrived in the Far West, eventually became those of Jim Cutlass, the other Giraud/Charlier western.

J.M. Lofficier has translated the biography in English, specifically for inclusion in the Graphitti Designs anthology collection, published in the fourth volume of the collection, Moebius #4. Lofficier however, took it upon himself to slightly edit Charlier's original text in order to reflect Blueberry's life as featured in the post-1974 publications (despite being reprinted numerous times, not only in French but in other languages as well,[90] Charlier himself has never revisited his original text again), and as such it is not an entirely faithful translation as some elements were added, whereas some others were omitted, such as the aforementioned notion of Blueberry ultimately heading a unit of Apache scouts.

Legacy

Awards

The series has received wide recognition in the comics community, and the chief factor for Giraud receiving his first recorded international award in 1973. Listed are only those rewards, the author(s) received specifically for Blueberry, as Giraud in particular received an additional multitude of awards and nominations for his work as "Mœbius" from 1977 onward, including awards encompassing his entire body of works.

- 1973: Shazam Award of the Academy of Comic Book Arts for Lieutenant Blueberry in the category "Best Foreign Comic Series".[91]

- 1975: Yellow Kid Salon Award, Lucca, Italy, in the category "Best Foreign Artist", Giraud only.[92]

- 1979: Adamson Award, Sweden, in the category "Best International Comic Series".[93]

- 1991: Harvey Award for the Blueberry saga published by Epic, in the category "Best American Edition of Foreign Material".[94]

- 1997: Eisner Award nomination for The Blueberry Saga #1: The Confederate Gold published by Mojo Press, in the category "Best Archival Collection".[95]

Adaptations

A 2004 film adaptation, Blueberry[96](U.S. release title is Renegade), was directed by Jan Kounen and starred Vincent Cassel in the lead role, with Giraud himself making a walk-on cameo appearance in the movie. Many purists were appalled by this film.[97]

Notes and references

- 1 2 R.J.M. Lofficier: Before Nick Fury, There was... Lieutenant Blueberry in Marvel Age #79 October, 1989.

- ↑ lambiek.net

- ↑ Lofficier, Jean-Marc (December 1988). "Moebius". Comics Interview (64). Fictioneer Books. pp. 24–37.

- ↑ Date and place of birth as provided by co-creator Charlier in his fictional Blueberry biography included in the 1974 book Ballade pour un cercueil.

- 1 2 Afterword by Jean-Michel Charlier in Blueberry 2: Ballad for a Coffin. Epic Comics. 1989 ISBN 0-87135-570-1

- ↑ Lambiek Comiclopedia. "Jean Giraud".

- ↑ BDoubliées. "Pilote année 1963" (in French).

- ↑ TVtropes.com

- ↑ Video.google.com

- ↑ Bdoubliees.com; where applicable, the introduction plates, as were some of the magazine covers, were included in the American Epic publications.

- ↑ Bdoubliees.com

- ↑ Bdoubliees.com

- ↑ Bdoubliees.com

- ↑ Bdoubliees.com

- 1 2 3 A very notable exception had been Croatia, where the format has managed to persevere, as recent as the late 2000s/early 2010s.

- ↑ tebeosfera.com

- ↑ de Bree, 1982, p. 39

- 1 2 stripspeciaalzaak.be

- ↑ Jurgeit, 2003, p. 10

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ BLIMEY! The Blog of British Comics from the Past, Present and Future!

- ↑ Dargaud International Publishing, Ltd. Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 According to Bedetheque.com; The French books were until volume 18 published in simultaneous conjuncture with Belgian publisher Le Lombard who released these for French-Belgium, initially as soft cover editions, contrary to Dargaud who released these from the start as hard cover books. The same also held true for the first three Young Blueberry titles, then part of the main series. For expedience sake only the French editions from the parent publisher are mentioned. ISBN numbers were not issued until 1975, the Lombard releases actually never receiving any.

- ↑ "Le hors-la-loi" literally translates as "'The one outside the law", in meaning the exact same as "L'outlaw". France however, is one the few European countries where the use of anglicisms is actively discouraged by cultural authorities, resulting in the use of the more laborious expression as the book title.

- ↑ Volumes 19-21 were in France and French-Belgium simultaneously released by two different publisher, albeit under the same ISBN number. The French publisher is listed first.

- ↑ In France, and at a later point in time in French-Belgium – the actual birthplace of the modern European comic – as well, comics are invariably considered, and officially recognized, as le neuvième art (the 9th art), in no small part due to the efforts in the 1980s of French minister of culture, Jack Lang. While the expression is also used in other countries, albeit unofficially, none have afforded the medium the same status.

- ↑ Sadoul, 1991, p. 71

- ↑ The Lost Dutchman's Mine diptych is by many critics considered as Giraud's magnus opus as far as Blueberry is concerned, becoming the primary agent for his 1973 Shazam Award, and having been in some countries – Hungary and Japan (OCLC 805927727) – the only titles translated thusfar, whereas France and other countries have given the two titles preferential treatment by reissuing them as separate "deluxe" anthologies on several occasions (stripinfo.be).

- ↑ US History in Context

- ↑ blueberrybr.blogspot.nl; Giraud created "Three Black Birds" originally in black and white and as such it was reprinted in the Mojo Press publication. Two years later though, Giraud himself provided the ink wash coloring for the story when it was reprinted in the western art book Blueberry's (ISBN 2908706024), followed by color reprints in the French magazine Bodoï, issue 10, 1998 and the German magazine Comixene, issue 64, 2003. In the latter, Giraud explained his creative thought processes for the coloring in an editorial.

- ↑ This appears to be a made-up name as a historical Tonto Apache chieftain is known to have existed, who went by the exact same nickname, which however was the in Tonto-Apache radically different coined "Chan-deisi".

- ↑ de Bree, 1982, p. 39, also mentioned in the original French version of the Blueberry biography.

- ↑ stripspeciaalzaak.be

- ↑ Pizolli, 1997, p. 91

- ↑ tebeosfera.com

- ↑ bdportugal.info

- ↑ fumetto-online.it

- ↑ comicguide.de

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ alvglans.se

- ↑ comicwiki.dk

- ↑ minetegneserier.no

- ↑ komiks.polter.pl

- ↑ sarjakuvat.eurocomics.info

- ↑ stripovi.com

- ↑ hu:Blueberry (képregény)

- ↑ mamouthcomix.gr

- ↑ myndasogur.is

- ↑ hermeskitap.com

- ↑ tokobukukomik.pasarberingharjo.com

- ↑ These included among others such publishers as es:Grupo Editorial Vid for Mexico, as well as Vecchi, Abril and (Brazilian branch) Panini Comics for Brasil.

- ↑ Publisher Bookglobe for Croatia, and Marketprint for Serbia.

- ↑ In Zack magazine, issues 19-23, 1972 (after having been published in MickyVision Comix, issues 47-3, 1968/69), followed by the books Der Mann mit dem Silberstern as stop-gap, and Aufruhr im Westen (Koralle, 1973 and 1977 respectively)

- ↑ Dreiging in het westen (Le Lombard/Helmond, 1971)

- ↑ Mannen med silverstjärnan (Sweden, Semic Press, 1971); Manden med sølvstjernen (Denmark, dk:Interpresse, 1972); Mannen med sølvsjternen (Norway, Romanforlaget, 1972)

- ↑ Jurgeit, Martin. "Rückkeht der fehlenden Blueberry-Abenteur", The Tombstone Epitaph Nr.1, p. 1, INK Verlag Jurgeit, Krissman & Nobst GbR, Berlin, 2003

- ↑ Previous 1967 and 1972, Italian and Yugoslav respective releases, were legally and technically magazine publications, therefore falling under the syndication regime (stripinfo.be)

- ↑ lion-muthucomics.blogspot.in

- ↑ bedetheque.com

- ↑ de Bree, 1982, p. 64

- ↑ Blueberry i den Amerikanske borgerkrig, Interpresse, 1990, ISBN 8745607222, lacking the "Thunder on the Sierra" short.

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ Das Geheimnis des Mike S. Donovan (ISBN 3770429842, Germany), Ungdom og borgerkrig (ISBN 8776792749, Denmark) and Ungdom og borgerkrig (ISBN 8242928665, Norway), all 2006

- ↑ Blueberry-Werkausgabe: comicforum.de; stripinfo.be

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ Blueberry Sonderband, Jurgeit, Krismann & Nobst, Berlin, Germany, 2003, OCLC 314617606 and Bluberijeva mladost, Crazy Cow "pirated edition", Croatia, 2003

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- 1 2 Sadoul, 1991; Giraud has never been shy about the subject of mind-expanding substances, frankly admitting their use in numerous interviews and discussing it in-depth in, among others, the interview book Moebius: Entretiens avec Numa Sadoul.

- 1 2 Svane, 2003, p. 45

- ↑ NeoBlek magazine for Iceland, and tr:Doğan Kardeş magazine for Turkey, though neither country has seen book publications as of 2016.

- ↑ stripspeciaalzaak.be

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ Ledoux, 2003, p. 66 (quoted from the Winter 1996 Sapristi!, issue 36, magazine interview)

- ↑ De Telegraaf, 2 April 1982, in which it is stated that the Dutch first printing of La tribu fantôme numbered 30.000; at the time the rule of thumb was that Dutch-language first print runs numbered approximately 10%-15% of that of their French counterparts, reflecting to some extent the relative sizes of the French, and Dutch speaking European populaces. Furthermore, since Dutch first print releases traditionally number in the 5.000-15.000 range for the vast majority of comic titles – discounting those few blockbuster staples such as Asterix – it was also indicative of the immense popularity main series Blueberry enjoyed at that time.

- ↑ Ledoux, 2003, p. 66

- ↑ Svane, 2003, pp. 71-72

- ↑ Svane, 2003, p. 68; Though not Blueberry, Rouge did take over the Comanche series ten years later, that other famed contemporary Franco-Belgian western comic series, second only in renown after Blueberry at the time, which was abandoned by its co-creator, artist Hermann Huppen. Unfortunately, Rouge was not able to regain the popularity the series once had, when it was still penciled by Hermann, and the series was suspended definitely after Rouge had only added five titles to the series.

- ↑ Förster, Svane, 2003, pp. 12, 35

- ↑ stripspeciaalzaak.be; comicwiki.dk

- ↑ Jurgeit, 2003, p. 12

- ↑ Actually, after a historical photograph (blueberrybr.blogspot.nl)

- ↑ comics.org

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ Bosser, 2005, p. 74; Blueberry: De mijn van Prosit & Het spook van de goudmijn, p. 4, Stichting Sherpa, Castricum, 2011, ISBN 9789089880178.

- ↑ Previously, Le spectre aux balles d'or, had run four pages over-length, which, not being a multitude of eight, had been a bother for the contemporary printer as it resulted in excess paper waste.

- ↑ In the Netherlands for example, it was the popular science magazine Kijk of March 1977 (pp. 42-44) where the edited article was presented to its readership as factual history.

- ↑ Collective, 1986, p. 22

- ↑ Berner, 2003, p. 26 (quoted from the April 1978 Schtroumpf: Les Cahiers De La Bd magazine interview)

- ↑ http://pabd.free.fr/BLUEBERY/BLUEBERY.HTM

- ↑ stripinfo.be

- ↑ 1973 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards

- ↑ "11° Salone Internationale del Comics, del Film di Animazione e dell'Illustrazione" (in Italian). immaginecentrostudi.org.

- ↑ Comic Book Awards Almanac. "Adamson Awards".

- ↑ 1991 Harvey Award Nominees and Winners; Giraud had already received the same price in 1988 and 1989 for the Mœbius and Incal collections by Epic.

- ↑ 1997 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees and Winners

- ↑ IMDB.com Movie (Renegade)

- ↑ Blueberry - Edition Collector, Fnac

Further reading

- de Bree, Kees; Frederiks, Hans (1982). Stripschrift special 4: Blueberry, Arzach, Majoor Fataal, John Difool, de kleurrijke helden van Giraud/Moebius. Zeist: Vonk. p. 100. OCLC 63463307.

- Bosser, Frédéric (2005). Dossier Jean Giraud: Cavalier solitaire (Les dossiers de la bande dessinée, issue 27 ed.). Paris: DBD. p. 96.

- Hjorth-Jørgensen, Anders (1984). Giraud/Moebius - og Blueberrys lange march. Stavnsager: Odense. p. 100. ISBN 8788455262.

- Collective (1986). L'univers de 1: Gir. Paris: Dargaud. p. 96. ISBN 2205029452.

- Sadoul, Numa (1991). Entretiens avec Moebius. Tournai: Casterman. p. 198. ISBN 2203380152.

- Pizzoli, Daniel (1995). Il était une fois Blueberry. Paris: Dargaud. p. 96. ISBN 2205044788.

- Pizzoli, Daniel (1997). Ein Yankee namens Blueberry (German language version of the 1995 Dargaud ed.). Stuttgart: Ehapa. p. 96. ISBN 2205044788.

- Svane, Erik; Surmann, Martin; Ledoux, Alain; Jurgeit, Martin; Berner, Horst; Förster, Gerhard (2003). Zack-Dossier 1: Blueberry und der europäische Western-Comic. Berlin: Mosaik. p. 96. ISBN 393266759X.

- de la Croix, Arnaud (2007). Blueberry : une légende de l'Ouest. Bruxelles: Edition Point Image. p. 100. ISBN 9782930460086.

External links

- Blueberry official site (French)

- Blueberry on Jean-Michel Charlier's website (French)

- Fort Navajo and Blueberry publications in Pilote BDoubliées (French)