Brassaï

| Brassaï (Gyula Halász) | |

|---|---|

|

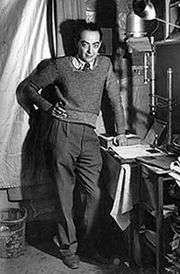

Self-photoportrait of Brassaï | |

| Born |

Gyula Halász 9 September 1899 Brassó, Transylvania, Austria-Hungary (now Romania) |

| Died |

8 July 1984 (aged 84) Beaulieu-sur-Mer, France |

| Nationality | Hungarian/French |

| Alma mater | Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse(s) | Gilberte Brassai |

Brassaï (French: [bʁasaj]; pseudonym of Gyula Halász; 9 September 1899 – 8 July 1984) was a Hungarian–French photographer, sculptor, writer, and filmmaker who rose to international fame in France in the 20th century. He was one of the numerous Hungarian artists who flourished in Paris beginning between the World Wars. In the early 21st century, the discovery of more than 200 letters and hundreds of drawings and other items from the period 1940–1984 has provided scholars with material for understanding his later life and career.

Early life and education

Gyula (Julius) Halász Brassaï (pseudonym) was born at 9 September 1899 in Brasov, Romania to an Armenian mother and a Hungarian father. He grew up speaking Hungarian and Romanian.[1] When he was three, his family lived in Paris for a year, while his father, a professor of French literature, taught at the Sorbonne.

As a young man, Gyula Halász studied painting and sculpture at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts (Magyar Képzőművészeti Egyetem) in Budapest. He joined a cavalry regiment of the Austro-Hungarian army, where he served until the end of the First World War.

He cited Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as an artistic influence.[2]

Career

In 1920, Halász went to Berlin, where he worked as a journalist for the Hungarian papers Keleti and Napkelet.[3] He started studies at the Berlin-Charlottenburg Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule für Bildende Künste), now Universität der Künste Berlin. There he became friends with several older Hungarian artists and writers, including the painters Lajos Tihanyi and Bertalan Pór, and the writer György Bölöni, each of whom later moved to Paris and became part of the Hungarian circle.[4]

In 1924, Halasz moved to Paris to live, where he would stay for the rest of his life. To learn the French language, he began teaching himself by reading the works of Marcel Proust. Living among the gathering of young artists in the Montparnasse quarter, he took a job as a journalist. He soon became friends with the American writer Henry Miller, and the French writers Léon-Paul Fargue and Jacques Prévert. In the late 1920s, he lived in the same hotel as Tihanyi.[4]

Miller later played down Brassai's claims of friendship. In 1976 he wrote of Brassai: "Fred [Perles] and I used to steer shy of him - he bored us." Miller added that the biography Brassai had written of him was typically "padded", "full of factual errors, full of suppositions, rumors, documents he filched which are largely false or give a false impression."[5]

Halász's job and his love of the city, whose streets he often wandered late at night, led to photography. He first used it to supplement some of his articles for more money, but rapidly explored the city through this medium, in which he was tutored by his fellow Hungarian André Kertész. He later wrote that he used photography "in order to capture the beauty of streets and gardens in the rain and fog, and to capture Paris by night."[6] Using the name of his birthplace, Gyula Halász went by the pseudonym "Brassaï," which means "from Brasso."

Brassaï captured the essence of the city in his photographs, published as his first collection in the 1933 book entitled Paris de nuit (Paris by Night). His book gained great success, resulting in being called "the eye of Paris" in an essay by his friend Henry Miller. In addition to photos of the seedier side of Paris, Brassai portrayed scenes from the life of the city's high society, its intellectuals, its ballet, and the grand operas. He had been befriended by a French family who gave him access to the upper classes. Brassai photographed many of his artist friends, including Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, and several of the prominent writers of his time, such as Jean Genet and Henri Michaux.

Young Hungarian artists continued to arrive in Paris through the 1930s and the Hungarian circle absorbed most of them. Kertèsz immigrated to New York in 1936. Brassai befriended many of the new arrivals, including Ervin Marton, a nephew of Tihanyi, whom he had been friends with since 1920. Marton developed his own reputation in street photography in the 1940s and 1950s. Brassaï continued to earn a living with commercial work, also taking photographs for the United States magazine Harper's Bazaar.[6] He was a founding member of the Rapho agency, created in Paris by Charles Rado in 1933.

Brassaï's photographs brought him international fame. In 1948, he had a one-man show in the [United States] at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City, which traveled to the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York; and the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois.[7] MOMA exhibited more of Brassai's works in 1953, 1956, and 1968.[8] He was presented at the Rencontres d'Arles festival (France) in 1970 (screening at the Théâtre Antique, "Brassaï" by Jean-Marie Drot), in 1972 (screening "Brassaï si, Vominino" by René Burri), and in 1974 (as guest of honor).

Marriage

In 1948, Brassaï married Gilberte Boyer, a French woman. She worked with him in supporting his photography. In 1949, he became a naturalized French citizen after years of being stateless.[9]

Publications

- Brassai, Henry Miller: The Paris Years, Arcade Publishing, 1975

- Brassai (1976). The Secret Paris of the 30's. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27108-9.

- Brassai, Letters to My Parents, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997

- Brassai, Conversations with Picasso, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1999

References

- ↑ About.com Archived January 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. "Brassaï's father was Hungarian, a professor of French Literature at the University of Brassó, but his mother was of Armenian origin."

- ↑ "Brassaï" in Horst Woldemar Janson, Anthony F. Janson, History of Art: The Western Tradition. Prentice Hall Professional, 2004. ISBN 978-0-13-019732-0

- ↑ Brassai, Letters to My Parents, 1997, p. 8

- 1 2 Brassai, Letters to My Parents, University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 241. Accessed 6 Sep 2010

- ↑ The Durrell-Miller Letters, 1935-80, Ed. Ian S. Macniven, Faber & Faber, 1988

- 1 2 Alain Sayag, ed., Brassai: The Monograph, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 2000.

- ↑ "Brassai Biography" Archived February 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Photo-Seminars, accessed 2 Sep 2010

- ↑ Brassai, Letters to My Parents, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997, p. xviii, accessed 2 Sep 2010

- ↑ "Brassai", Prodan Romanian Cultural Foundation, accessed 2 Sep 2010

Bibliography

- Tucker, Anne Wilkes, with Richard Howard and Avis Berman. Brassaï: The Eye of Paris. Houston, TX: Houston Museum of Fine Arts, 1997. ISBN 0-8109-6380-9

- Marja Warehime, Brassaï: Images of Culture and the Surrealist Observer. LSU Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8071-2276-9

External links

- Brassaï at the Art Institute of Chicago

- "Brassaï" at Masters of Photography

- Brassai: The Transylvanian Parisian, I Photo Central

- Collection Rijksmuseum

- Brassaï's exhibition at Fundació Antoni Tàpies

- Brassai's Cats