Bunhill Fields

|

Monuments in Bunhill Fields burial ground | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1665 |

| Location | London Borough of Islington |

| Country | England |

| Type | Public (closed) |

| Owned by | City of London Corporation |

| Size | 1.6 hectares (4.0 acres) |

| Number of graves | 120,000 |

Bunhill Fields is a former burial ground in the London Borough of Islington, north of the City of London, now managed as a public garden by the City of London Corporation. It is about 1.6 hectares (4.0 acres) in extent,[1] although historically it was much larger.

It was in use as a burial ground from 1665 until 1854, by which date approximately 123,000 interments were estimated to have taken place. Over 2,000 monuments remain.[2] It was particularly favoured by Nonconformists, and contains the graves of many notable people, including John Bunyan (died 1688), author of The Pilgrim's Progress; Daniel Defoe (died 1731), author of Robinson Crusoe; William Blake (died 1827), artist, poet, and mystic; Susanna Wesley (died 1742), known as the "Mother of Methodism" through her education of sons John and Charles; Thomas Bayes (died 1761), statistician and philosopher; and Isaac Watts (died 1748), the "Father of English Hymnody".

Nearby was a separate Quaker burial ground, sometimes also known by the name Bunhill Fields, which was in use from 1661 to 1855. George Fox (died 1691), one of the founders of the Quaker movement, was among those buried here. Its remains are also now a public garden, Quaker Gardens, managed by the London Borough of Islington.

Historical background

Bunhill Fields was part of the Manor of Finsbury (originally Fensbury), which has its origins as the prebend of Halliwell and Finsbury, belonging to St Paul's Cathedral and established in 1104. In 1315 the prebendary manor was granted by Robert Baldock to the Mayor and commonalty of London. This act enabled more general public access to a large area of fen or moor stretching from the City of London's boundary (London Wall), to the village of Hoxton.

In 1498 part of the otherwise unenclosed landscape was set aside to form a large field for military exercises of archers and others. This part of the manor still bears the name "Artillery Ground".

Next to this lies Bunhill Fields. The name derives from "Bone Hill", which is possibly a reference to the district having been used for occasional burials from at least Saxon times, but more probably derives from the use of the fields as a place of deposit for human bones – amounting to over 1,000 cartloads – brought from St Paul's charnel house in 1549 when that building was demolished.[3] The dried bones were deposited on the moor and capped with a thin layer of soil. This built up a hill across the otherwise damp, flat fens, such that three windmills could safely be erected in a spot that came to be known as Windmill Hill.

Opening as a burial ground

In keeping with this tradition, in 1665 the City of London Corporation decided to use some of the fen as a common burial ground for the interment of bodies of inhabitants who had died of the plague and could not be accommodated in the churchyards. Although enclosing walls for the burial ground were completed, Church of England officials never consecrated the ground or used it for burials. A Mr Tindal took over the lease.

He allowed extramural burials in its unconsecrated soil, which became popular with Nonconformists – those Protestant Christians who practised their faith outside the Church of England: unlike Anglican parish churchyards, the burial ground was open for interment to anyone who could afford the fees. It appears on Rocque's Map of London of 1746, and elsewhere, as "Tindal's Burying Ground".

An inscription at the eastern entrance gate to the burial ground reads: "This church-yard was inclosed with a brick wall at the sole charges of the City of London, in the mayoralty of Sir John Lawrence, Knt., Anno Domini 1665; and afterwards the gates thereof were built and finished in the mayoralty of Sir Thomas Bloudworth, Knt., Anno Domini, 1666." The present gates and inscription date from 1868, but the wording follows that of an original 17th-century inscription at the western entrance, now lost.[2]

The earliest recorded monumental inscription was that to "Grace, daughter of T. Cloudesly, of Leeds. February 1666".[4] The earliest surviving monument is believed to be the headstone to Theophilus Gale: the inscription reads "Theophilus Gale MA / Born 1628 / Died 1678".[5]

In 1769 an Act of Parliament gave the City of London Corporation the right to continue to lease the ground from the prebendal estate for 99 years. The City authorities continued to let the ground to their tenant as a burial ground; in 1781 the Corporation decided to take over management of the burial ground.

So many historically important Protestant Nonconformists chose this as their place of interment that the 19th-century poet and writer Robert Southey characterised Bunhill Fields as "the Campo Santo of the Dissenters." This term was also later applied to its "daughter" cemetery established at Abney Park in Stoke Newington.

Closure as a burial ground

In 1852 the Burial Act was passed which enabled burial grounds to be closed once they became full. An Order for Closure for Bunhill Fields was made in December 1853, and the final burial (that of Elizabeth Howell Oliver) took place on 5 January 1854. Occasional interments continued to be permitted in existing vaults or graves: the final burial of this kind is believed to have been that of a Mrs Gabriel of Brixton in February 1860.[6] By this date approximately 123,000 interments had taken place in the burial ground.[7]

Two decades before, a group of City Nonconformists led by George Collison secured a site for a new landscaped alternative, at part of Abney Park in Stoke Newington. This was named Abney Park Cemetery and opened in 1840. All parts were available for the burial of any person, regardless of religious creed. Abney Park Cemetery was the only Victorian garden cemetery in Britain with "no invidious dividing lines" and a unique nondenominational chapel, designed by William Hosking.

Community garden

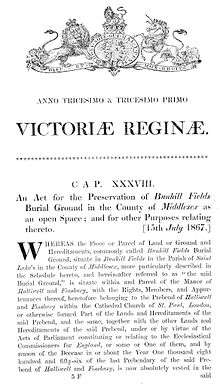

Following closure of the Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, its future was uncertain as its lessee, the City of London Corporation, was close to expiry of its lease, scheduled for Christmas 1867. To prevent the land from being developed at expiry of the lease, the Corporation formed the Special Bunhill Fields Burial Ground Committee in 1865, which became formally known as the Bunhill Fields Preservation Committee.

Appointed by the Corporation, the committee consisted on twelve advisors under the chairmanship of Charles Reed, FSA (son of the Congregational philanthropist Dr Andrew Reed). Charles Reed later rose to prominence as the first MP for Hackney and Chairman of the first School Board for London before being knighted. Along with his interest in making Bunhill Fields into a parkland landscape, he was similarly interested in the wider educational and public benefits of Abney Park Cemetery, of which he was a prominent director.

Following the committee's work, the City of London Corporation obtained an Act of Parliament, the Bunhill Fields Burial Ground Act 1867,[1] "for the Preservation of Bunhill Fields Burial Ground ... as an open space". The legislation enabled the corporation to continue to maintain the site when the freehold reverted to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, provided it was laid out as a public open space with seating, gardens, and some of its most worthy monuments were restored. The improvements, which included the laying out of walks and paths, cost an estimated £3,500. The new park was opened by the Lord Mayor, James Clarke Lawrence, on 14 October 1869.[6]

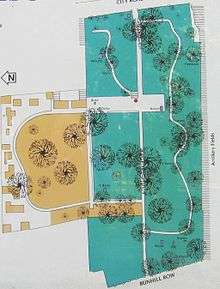

The burial ground was severely damaged by German bombing during World War II. It is also believed to have been the location of an anti-aircraft gun during the Blitz.[2] In the 1950s, after some debate, the decision was taken to clear the northern third of the site of most of its monuments and open it as a public garden with open access, while preserving and protecting the remainder of the site behind railings. Legislation in 1960 transferred the freehold to the City of London Corporation, which continues to maintain the grounds. The work of landscaping was undertaken by the architect and landscape architect Peter Shepheard in 1964–65.[2][8]

In February 2012, Occupy London opened a site in the northwestern corner of Bunhill Fields to replace their Bank of Ideas at Sun Street.

Bunyan, Defoe and Blake

The three best-known monuments are those to the literary and artistic figures, John Bunyan, Daniel Defoe and William Blake. They have long been sites of cultural pilgrimage: Isabella Holmes stated in 1896 that the "most frequented paths" in the burial ground were those leading to the monuments of Bunyan and Defoe.[9] Following the landscaping of 1964–65, all three monuments now stand in a paved north-south "broadwalk" in the middle of the burial ground, outside the railed-off areas, cleared of other monuments, and accessible to visitors. Bunyan's monument is at the broadwalk's southern end, and those to Defoe and Blake (along with a headstone for the lesser-known Joseph Swain, d. 1796) at its northern end. In their present form, all three monuments post-date the closure of the burial ground, and Blake's is not on the site of his grave.

John Bunyan

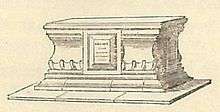

John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim's Progress, died in August 1688. He was initially buried in the "Baptist Corner" at the back of the burial ground, on the understanding that his remains would be moved into the family vault of his friend John Strudwick when that was next opened for a burial. There is no certain evidence as to when (or even if) this was done: the probability, however, is that it occurred when Strudwick himself died in 1695, and certainly Bunyan's name was inscribed on the side of the monument.[10] The Strudwick monument took the form of a large Baroque stone chest. By the 19th century, this had fallen into decay, but in the period following the closure of the burial ground a public appeal for its restoration was launched under the presidency of the Earl of Shaftesbury. This work was completed in May 1862, and comprised a complete reconstruction of the monument, undertaken by the sculptor Edgar George Papworth senior (1809–66).[11] Although Papworth retained the basic form of the tomb-chest, he added a recumbent effigy of Bunyan to the top of it, and two relief panels to its sides depicting scenes from Pilgrim's Progress. The monument was further restored in 1928 (the tercentenary of Bunyan's birth), and again after World War II (following serious wartime damage to the effigy's face).[12]

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, died in April 1731 and was buried in Bunhill Fields: his wife, Mary, died in December 1732 and was laid to rest beside him. His daughter-in-law was also buried in the same grave. Defoe died in poverty, and the grave was marked with a simple headstone. In the winter of 1857/8 – at a time when the burial ground was closed and neglected – the grave was struck by lightning and the headstone broken. In 1869, James Clarke, editor of the Christian World children's newspaper, launched an appeal for subscriptions to place a more suitable memorial on the grave. He encouraged his readers to make donations of sixpence each; and to stimulate enthusiasm opened two lists, one for boys and one for girls, to encourage a spirit of competition between them. Many adults also made donations. In the end, some 1,700 subscriptions raised a total of about £200. A design for a marble obelisk (or "Cleopatric pillar") was commissioned from C.C. Creeke; and the sculptor Samuel Horner of Bournemouth was commissioned to execute it. In late 1869, when the foundations were being dug, skeletons were disinterred, and there was an unseemly rush for souvenirs by the crowd of onlookers: the police had to be called before calm was restored. The monument was unveiled at a ceremony attended by three of Defoe's great-granddaughters on 16 September 1870.[13][14]

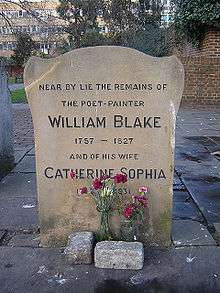

William Blake

William Blake – painter, poet, printmaker and visionary – died in August 1827 and was buried in the northern part of the burial ground. His wife, Catherine Sophia, died in October 1831 and was buried in a separate grave on the south side. By the 20th century, his grave was in disrepair, and in 1927, for the centenary of his death and at a time when his reputation was on the rise, a new headstone was commissioned. It commemorated both William and Catherine, and so, as it was not on the site of Catherine's grave, the inscription was phrased as "Near by lie the remains of ...". When Bunhill Fields was relandscaped in the 1960s, Blake's grave lay in the area that was to be cleared of monuments. The headstone was therefore moved approximately 20 metres to its present location, next to the monument to Daniel Defoe. It was also rotated through 90°, so that it now faces south rather than west.[15] Joseph Swain's headstone was added to the grouping at the same time, although that faces west.[2] In 2006–7, members of the group The Friends of William Blake rediscovered the original site of the grave, and made plans to place a permanent memorial there.[16][17] Flowers, coins and other tokens are regularly left by visitors to Blake's headstone.

Records

The Bunhill Fields burial ground registers, running from 1713 to 1854, are now held at The National Archives at Kew.[18] Other records, including interment order books dating from 1789 to 1854, and a record of the inscriptions as they were in 1869, are held at London Metropolitan Archives.

The College of Arms holds six volumes of inscriptions transcribed by the Baptist minister John Rippon in the early 19th century, copied while "laying on his side". Rippon himself was buried at Bunhill Fields in 1836.[19]

Notable graves

Notable burials include:

- Stephen Addington (1729–1796), dissenting clergyman and teacher

- William Aldridge (1737–1797), nonconformist minister

- Thomas Amory (1701–1774), dissenting minister, tutor and poet

- John Asty (c.1672–1730), dissenting clergyman

- Joshua Bayes (1671–1746), nonconformist minister

- Thomas Bayes (1702–1761), mathematician, clergyman, and friend of Richard Price

- Thomas Belsham (1750–1829), Unitarian minister

- William Blackburn (1750–1790), architect and surveyor

- Catherine Blake (1762–1831), wife of William Blake

- William Blake (1757–1827), painter, engraver, poet, and mystic

- David Bradberry (1736–1803), nonconformist minister

- Thomas Bradbury (1677–1759), congregational minister

- John Bradford (1750–1805), dissenting minister

- Thomas Brand (1635–1691), nonconformist minister and divine

- John Brine (1703–1765), Particular Baptist minister

- Charles Buck (1771–1815), Independent minister and theological writer, known for his Theological Dictionary

- John Bunyan (1628–1688), author of The Pilgrim's Progress

- George Burder (1752–1832), Nonconformist divine

- Thomas Fowell Buxton (1758–1795), father of Thomas Folwell Buxton, anti-slavery philanthropist

- Samuel Chandler (1693–1766), Nonconformist minister

- John Clayton (1754–1843), Independent minister

- Eleanor Coade (1733–1821), pioneer of the artificial stone known as Coade stone

- Thomas Cole (1628–1697), Independent minister

- Dr John Conder (1714–1781), President of Homerton College

- James Coningham (1670–1716), presbyterian divine and tutor

- Thomas Cotton (1653–1730), dissenting minister

- Cromwell family: two tombs commemorate various 18th-century members of this family, including Hannah Cromwell née Hewling (1653–1732), widow of Major Henry Cromwell (1658–1711), the grandson of Oliver Cromwell; together with several of the couple's children and grandchildren. (Major Cromwell himself died and was buried in Lisbon.)

- Daniel Defoe (1661–1731), author of Robinson Crusoe

- David Denham (1791–1848), Baptist minister, who in 1837 published The Saints' Melody. A New Selection of upwards of One Thousand Hymns, Founded Upon the Doctrines of Distinguishing Grace, and Adapted to every Part of the Christian Experience and Devotion in the Ordinances of Christ, etc., a compilation of 1,026 hymn texts (later editions contained 1,145 texts) still in use today

- Joseph Denison (c.1726–1806), banker

- Thomas Doolittle (?1632–1707), nonconformist minister, tutor and author

- John Eames (died 1744), dissenting tutor

- Thomas Emlyn (1663–1741), nonconformist divine

- Lady Anne Agnes Erskine (1739–1804), daughter of Henry Erskine, 10th Earl of Buchan; companion and trustee of Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, and treasurer of her charities

- John Evans (?1680–1730), Welsh presbyterian minister and historian

- John Faldo (1633–1690), nonconformist minister and controversialist

- John Fell (1735–1797), congregationalist minister and classical tutor

- Daniel Fisher (1731–1807), dissenting minister

- Lt. Gen. Charles Fleetwood (c.1618–1692), fought on the Parliamentarian side in the English Civil War, served as Lord Deputy of Ireland 1652–55, and married Bridget, eldest daughter of Oliver Cromwell

- Caleb Fleming (1698–1779), dissenting minister and polemicist

- Roger Flexman (1708–1795), presbyterian minister, historical scholar and bibliographer

- James Foster (1697–1753), Baptist minister and author of Essay on Fundamentals, one of the first nonconformist texts

- Philip Furneaux (1726–1783), independent minister

- Theophilus Gale (1628–1678), nonconformist minister, educationalist and theologian

- Thomas Gibbons (1720–1785), nonconformist minister, hymn writer and poet

- Andrew Gifford (1700–1784), Baptist minister and numismatist

- John Gill (1697–1771), Baptist pastor, biblical scholar, and Calvinist theologian, author of the Exposition of the Bible and the Body of Divinity

- Thomas Goodwin (1600–1680), Puritan theologian and preacher

- John Guyse (1680–1761), independent minister

- Charles Hamilton (?1753–1792), orientalist, known for his English translation of Al-Hidayah

- Joseph Hardcastle (1752–1819), one of the founders of the Missionary Society

- Thomas Hardy (1752–1832), political reformer and founder of the London Corresponding Society

- William Harris (?1675–1740), presbyterian minister

- Joseph Hart (1712–1768), hymn writer and Calvinist minister in London

- Thomas Heaphy the elder (1775–1835), watercolourist and portrait-painter

- William Hooke or Hook (1600–1677), Puritan clergyman

- Jabez Carter Hornblower (1744–1814), steam engine pioneer

- Francis Howell (1625–1679), Principal of Jesus College, Oxford, from 1657 to 1660

- Henry Hunter (1741–1802), Scottish minister and translator

- John Hyatt (1767–1826), one of the founding preachers of Calvinist Methodism at Whitefield's Tabernacle, Tottenham Court Road 1806–1828.

- Joseph Ivimey (1773–1834), Particular Baptist minister and historian

- William Jenkyn (1613–1685), nonconformist minister, imprisoned during the Interregnum

- Henry Jessey (1603–1663), dissenting minister and scholar, founding member of the "Jacobites" (Puritan religious sect)

- William Jones (1762–1846), Welsh Baptist religious writer and bookseller

- William Kiffin (1616–1701), Baptist minister and wool-merchant

- Andrew Kippis (1725–1795), nonconformist clergyman and biographer

- Hanserd Knollys (1599–1691), Particular Baptist minister

- Nathaniel Lardner (1684–1768), theologian

- John Le Keux (1783–1846), English engraver

- Theophilus Lindsey (1723–1808), a founder of Unitarianism

- John Macgowan (1726–1780), Scottish Baptist minister and author

- John Martin (1741–1820), Particular Baptist minister

- Nathaniel Mather (1631–1697), Independent minister

- Paul Henry Maty (1744–1787), British Museum librarian

- Henry Miles (1698–1763), dissenting minister and scientific writer

- Roger Morrice (1628–1702), Puritan minister and political journalist

- David Nasmith (1799–1839), founder of the City Mission Movement

- Daniel Neal (1678–1743), independent minister and historian of Puritanism

- Christopher Ness (1621–1705), independent minister and theological author

- Thomas Newcomen (1663–1729), steam engine pioneer (exact site of burial unknown)

- Joseph Nightingale (1775–1824), writer and preacher

- Joshua Oldfield (1656–1729), presbyterian divine

- William Orme (1787–1830), Scottish Congregational minister and biographer

- John Owen (1616–1683), Puritan divine, theologian, academic administratoe and statesman

- Dame Mary Page (1672–1729), wife of Sir Gregory Page, 1st Baronet

- Apsley Pellatt (1763–1826), glass manufacturer

- Edward Pickard (1714–1778), dissenting minister

- Richard Price (1723–1791), founder of life insurance principles

- Timothy Priestley (1734–1814), independent minister, and scientific collaborator with his brother Joseph Priestley

- Thomas Pringle (1789–1834), Scottish poet and author, and Secretary to the Anti-Slavery Society (re-interred 1970, Eildon Church, Baviaans valley, South Africa)

- Elizabeth Rayner (1714–1800), Unitarian benefactress

- Abraham Rees (1743–1825), Welsh nonconformist minister and compiler of Rees's Cyclopædia

- John Rippon (1750–1836), Baptist clergyman, composer of many well known hymns

- Benjamin Robinson (1666–1724), Presbyterian minister and theologian

- Samuel Rosewell (1679–1722), Presbyterian minister

- Thomas Rosewell (1630–1692), nonconformist minister of Rotherhithe

- John Rowe (1626–1677), nonconformist minister

- Thomas Rowe (1657–1705), nonconformist minister

- Samuel Morton Savage (1721–1791), nonconformist minister and dissenting tutor

- Samuel Say (1676–1743), dissenting minister

- Richard "Conversation" Sharp (1759–1835), prominent among the Dissenters' "Deputies", critic, merchant and MP

- William Shrubsole (1760-1806), singer and composer

- Samuel Stennett (1727–1795), Seventh Day Baptist minister and hymnwriter

- Thomas Stothard (1755–1834), painter, illustrator and engraver

- Joseph Swain (1761–1796), Baptist minister, poet and hymnwriter

- Charles Taylor (1756–1823), engraver and biblical scholar

- John Towers (?1747–1804), Independent minister

- Nathaniel Vincent (?1639–1697), nonconformist minister

- George Walker (c. 1734–1807), dissenter, mathematician, theologian, and Fellow of the Royal Society

- James Ware (1756–1815), eye surgeon and Fellow of the Royal Society

- Isaac Watts (1674–1748), hymn writer, educationalist and poet

- Rev Alexander Waugh (1754-1827) co-founder of the London Missionary Society and forbear of Evelyn Waugh

- Susanna Wesley (1669–1742), mother of John Wesley, founder of Methodism

- Daniel Williams (1643–1716), theologian and founder of Dr Williams's Library

- Hugh Worthington (1752–1813), dissenting minister

References

- 1 2 "Bunhill Fields Burial Ground". City of London. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Historic England. "Bunhill Fields Burial Ground (1001713)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ Holmes 1896, pp. 133–4.

- ↑ William Maitland, The History and Survey of London from its Foundation to the Present Time (London, 1756), p. 775

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument to Theophilus Gale, South Enclosure (1396557)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- 1 2 Corporation of London 1991, p. 8.

- ↑ Corporation of London 1991, pp. 4, 8.

- ↑ Corporation of London 1991, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Holmes 1896, p. 135.

- ↑ Philip, Robert (1839). The Life, Times and Characteristics of John Bunyan, author of the Pilgrim's Progress. London: Thomas Ward. pp. 578–80.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument to John Bunyan, Central Broadwalk (1396491)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ Winslow, Ola Elizabeth (1961). John Bunyan. New York: Macmillan. pp. 201–2.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument to Daniel Defoe, Central Broadwalk (1396492)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ Frank, Katherine (2011). Crusoe: Daniel Defoe, Robert Knox and the creation of a myth. London: Bodley Head. pp. 287–91. ISBN 9780224073097.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument to William and Catherine Sophia Blake, Central Broadwalk (1396493)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ "Cause For Celebration: The Location of William Blake's Grave discovered!". The Friends of William Blake. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ↑ "Coming up – William Blake". BBC Inside Out. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ↑ "Discover Our Collections". The National Archives. Retrieved 16 June 2014. References RG 4/3985–4001.

- ↑ Corporation of London 1991, p. 11.

Further reading

- Black, Susan E. (1990). Bunhill Fields: the great Dissenters' burial ground. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center.

- Corporation of London (1991). The Official Guide to Bunhill Fields. London: Corporation of London. ISBN 0-85203-033-9.

- Holmes, Mrs Basil [Isabella M.] (1896). The London Burial Grounds: notes on their history from the earliest times to the present day. London: T.F. Unwin. pp. 133–35.

- Jones, J. A., ed. (1849). Bunhill Memorials: sacred reminiscences of three hundred ministers and other persons of note, who are buried in Bunhill Fields, of every denomination. London: James Paul.

- Light, Alfred W. (1913–33). Bunhill Fields: written in honour and to the memory of the many saints of God whose bodies rest in this old London cemetery. London: C.J. Farncombe. (2 vols)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bunhill Fields. |

- Historic England. "Bunhill Fields Burial Ground (1001713)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Bunhill Fields Burial Ground". City of London. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

Coordinates: 51°31′25″N 0°05′20″W / 51.52361°N 0.08889°W