C (programming language)

|

The C Programming Language[1] (often referred to as "K&R"), the seminal book on C | |

| Paradigm | Imperative (procedural), structured |

|---|---|

| Designed by | Dennis Ritchie |

| Developer | Dennis Ritchie & Bell Labs (creators); ANSI X3J11 (ANSI C); ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG14 (ISO C) |

| First appeared | 1972[2] |

| Stable release |

C11

/ December 2011 |

| Typing discipline | Static, weak, manifest, nominal |

| OS | Cross-platform |

| Filename extensions | .c, .h |

| Major implementations | |

| GCC, Clang, Intel C, MSVC, Pelles C, Watcom C | |

| Dialects | |

| Cyclone, Unified Parallel C, Split-C, Cilk, C* | |

| Influenced by | |

| B (BCPL, CPL), ALGOL 68,[3] Assembly, PL/I, FORTRAN | |

| Influenced | |

| Numerous: AMPL, AWK, csh, C++, C--, C#, Objective-C, BitC, D, Go, Java, JavaScript, Julia, Limbo, LPC, Perl, PHP, Pike, Processing, Python, Rust, Seed7, Vala, Verilog (HDL)[4] | |

| |

C (/ˈsiː/, as in the letter c) is a general-purpose, imperative computer programming language, supporting structured programming, lexical variable scope and recursion, while a static type system prevents many unintended operations. By design, C provides constructs that map efficiently to typical machine instructions, and therefore it has found lasting use in applications that had formerly been coded in assembly language, including operating systems, as well as various application software for computers ranging from supercomputers to embedded systems.

C was originally developed by Dennis Ritchie between 1969 and 1973 at Bell Labs,[5] and used to re-implement the Unix operating system.[6] It has since become one of the most widely used programming languages of all time,[7][8] with C compilers from various vendors available for the majority of existing computer architectures and operating systems. C has been standardized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) since 1989 (see ANSI C) and subsequently by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

Design

C is an imperative procedural language. It was designed to be compiled using a relatively straightforward compiler, to provide low-level access to memory, to provide language constructs that map efficiently to machine instructions, and to require minimal run-time support. Therefore, C was useful for many applications that had formerly been coded in assembly language, for example in system programming.

Despite its low-level capabilities, the language was designed to encourage cross-platform programming. A standards-compliant and portably written C program can be compiled for a very wide variety of computer platforms and operating systems with few changes to its source code. The language has become available on a very wide range of platforms, from embedded microcontrollers to supercomputers.

Overview

Like most imperative languages in the ALGOL tradition, C has facilities for structured programming and allows lexical variable scope and recursion, while a static type system prevents many unintended operations. In C, all executable code is contained within subroutines, which are called "functions" (although not in the strict sense of functional programming). Function parameters are always passed by value. Pass-by-reference is simulated in C by explicitly passing pointer values. C program source text is free-format, using the semicolon as a statement terminator and curly braces for grouping blocks of statements.

The C language also exhibits the following characteristics:

- There is a small, fixed number of keywords, including a full set of flow of control primitives:

for,if/else,while,switch, anddo/while. User-defined names are not distinguished from keywords by any kind of sigil. - There are a large number of arithmetical and logical operators, such as

+,+=,++,&,~, etc. - More than one assignment may be performed in a single statement.

- Function return values can be ignored when not needed.

- Typing is static, but weakly enforced: all data has a type, but implicit conversions may be performed.

- Declaration syntax mimics usage context. C has no "define" keyword; instead, a statement beginning with the name of a type is taken as a declaration. There is no "function" keyword; instead, a function is indicated by the parentheses of an argument list.

- User-defined (

typedef) and compound types are possible.- Heterogeneous aggregate data types (

struct) allow related data elements to be accessed and assigned as a unit. - Array indexing is a secondary notation, defined in terms of pointer arithmetic. Unlike structs, arrays are not first-class objects; they cannot be assigned or compared using single built-in operators. There is no "array" keyword, in use or definition; instead, square brackets indicate arrays syntactically, for example

month[11]. - Enumerated types are possible with the

enumkeyword. They are not tagged, and are freely interconvertible with integers. - Strings are not a separate data type, but are conventionally implemented as null-terminated arrays of characters.

- Heterogeneous aggregate data types (

- Low-level access to computer memory is possible by converting machine addresses to typed pointers.

- Procedures (subroutines not returning values) are a special case of function, with an untyped return type

void. - Functions may not be defined within the lexical scope of other functions.

- Function and data pointers permit ad hoc run-time polymorphism.

- A preprocessor performs macro definition, source code file inclusion, and conditional compilation.

- There is a basic form of modularity: files can be compiled separately and linked together, with control over which functions and data objects are visible to other files via

staticandexternattributes. - Complex functionality such as I/O, string manipulation, and mathematical functions are consistently delegated to library routines.

While C does not include some features found in some other languages, such as object orientation or garbage collection, such features can be implemented or emulated in C, often by way of external libraries (e.g., the Boehm garbage collector or the GLib Object System).

Relations to other languages

Many later languages have borrowed directly or indirectly from C, including C++, D, Go, Rust, Java, JavaScript, Limbo, LPC, C#, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, Swift, Verilog (hardware description language),[4] and Unix's C shell. These languages have drawn many of their control structures and other basic features from C. Most of them (with Python being the most dramatic exception) are also very syntactically similar to C in general, and they tend to combine the recognizable expression and statement syntax of C with underlying type systems, data models, and semantics that can be radically different.

History

Early developments

The origin of C is closely tied to the development of the Unix operating system, originally implemented in assembly language on a PDP-7 by Ritchie and Thompson, incorporating several ideas from colleagues. Eventually, they decided to port the operating system to a PDP-11. The original PDP-11 version of Unix was developed in assembly language. The developers were considering rewriting the system using the B language, Thompson's simplified version of BCPL.[9] However B's inability to take advantage of some of the PDP-11's features, notably byte addressability, led to C. The name of C was chosen simply as the next after B.[10]

The development of C started in 1972 on the PDP-11 Unix system[11] and first appeared in Version 2 Unix.[12] The language was not initially designed with portability in mind, but soon ran on different platforms as well: a compiler for the Honeywell 6000 was written within the first year of C's history, while an IBM System/370 port followed soon.[1][11]

Also in 1972, a large part of Unix was rewritten in C.[13] By 1973, with the addition of struct types, the C language had become powerful enough that most of the Unix's kernel was now in C.

Unix was one of the first operating system kernels implemented in a language other than assembly. Earlier instances include the Multics system which was written in PL/I), and Master Control Program (MCP) for the Burroughs B5000 written in ALGOL in 1961. In around 1977, Ritchie and Stephen C. Johnson made further changes to the language to facilitate portability of the Unix operating system. Johnson's Portable C Compiler served as the basis for several implementations of C on new platforms.[11]

K&R C

.svg.png)

In 1978, Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie published the first edition of The C Programming Language.[1] This book, known to C programmers as "K&R", served for many years as an informal specification of the language. The version of C that it describes is commonly referred to as K&R C. The second edition of the book[14] covers the later ANSI C standard, described below.

K&R introduced several language features:

- Standard I/O library

-

long intdata type -

unsigned intdata type - Compound assignment operators of the form

=op(such as=-) were changed to the formop=(that is,-=) to remove the semantic ambiguity created by constructs such asi=-10, which had been interpreted asi =- 10(decrementiby 10) instead of the possibly intendedi = -10(letibe -10).

Even after the publication of the 1989 ANSI standard, for many years K&R C was still considered the "lowest common denominator" to which C programmers restricted themselves when maximum portability was desired, since many older compilers were still in use, and because carefully written K&R C code can be legal Standard C as well.

In early versions of C, only functions that return types other than int must be declared if used before the function definition; functions used without prior declaration were presumed to return type int.

For example:

long some_function();

/* int */ other_function();

/* int */ calling_function()

{

long test1;

register /* int */ test2;

test1 = some_function();

if (test1 > 0)

test2 = 0;

else

test2 = other_function();

return test2;

}

The int type specifiers which are commented out could be omitted in K&R C, but are required in later standards.

Since K&R function declarations did not include any information about function arguments, function parameter type checks were not performed, although some compilers would issue a warning message if a local function was called with the wrong number of arguments, or if multiple calls to an external function used different numbers or types of arguments. Separate tools such as Unix's lint utility were developed that (among other things) could check for consistency of function use across multiple source files.

In the years following the publication of K&R C, several features were added to the language, supported by compilers from AT&T (in particular PCC[15]) and some other vendors. These included:

-

voidfunctions (i.e., functions with no return value) - functions returning

structoruniontypes (rather than pointers) - assignment for

structdata types - enumerated types

The large number of extensions and lack of agreement on a standard library, together with the language popularity and the fact that not even the Unix compilers precisely implemented the K&R specification, led to the necessity of standardization.

ANSI C and ISO C

During the late 1970s and 1980s, versions of C were implemented for a wide variety of mainframe computers, minicomputers, and microcomputers, including the IBM PC, as its popularity began to increase significantly.

In 1983, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) formed a committee, X3J11, to establish a standard specification of C. X3J11 based the C standard on the Unix implementation; however, the non-portable portion of the Unix C library was handed off to the IEEE working group 1003 to become the basis for the 1988 POSIX standard. In 1989, the C standard was ratified as ANSI X3.159-1989 "Programming Language C". This version of the language is often referred to as ANSI C, Standard C, or sometimes C89.

In 1990, the ANSI C standard (with formatting changes) was adopted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) as ISO/IEC 9899:1990, which is sometimes called C90. Therefore, the terms "C89" and "C90" refer to the same programming language.

ANSI, like other national standards bodies, no longer develops the C standard independently, but defers to the international C standard, maintained by the working group ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG14. National adoption of an update to the international standard typically occurs within a year of ISO publication.

One of the aims of the C standardization process was to produce a superset of K&R C, incorporating many of the subsequently introduced unofficial features. The standards committee also included several additional features such as function prototypes (borrowed from C++), void pointers, support for international character sets and locales, and preprocessor enhancements. Although the syntax for parameter declarations was augmented to include the style used in C++, the K&R interface continued to be permitted, for compatibility with existing source code.

C89 is supported by current C compilers, and most C code being written today is based on it. Any program written only in Standard C and without any hardware-dependent assumptions will run correctly on any platform with a conforming C implementation, within its resource limits. Without such precautions, programs may compile only on a certain platform or with a particular compiler, due, for example, to the use of non-standard libraries, such as GUI libraries, or to a reliance on compiler- or platform-specific attributes such as the exact size of data types and byte endianness.

In cases where code must be compilable by either standard-conforming or K&R C-based compilers, the __STDC__ macro can be used to split the code into Standard and K&R sections to prevent the use on a K&R C-based compiler of features available only in Standard C.

After the ANSI/ISO standardization process, the C language specification remained relatively static for several years. In 1995, Normative Amendment 1 to the 1990 C standard (ISO/IEC 9899/AMD1:1995, known informally as C95) was published, to correct some details and to add more extensive support for international character sets.

C99

The C standard was further revised in the late 1990s, leading to the publication of ISO/IEC 9899:1999 in 1999, which is commonly referred to as "C99". It has since been amended three times by Technical Corrigenda.[16]

C99 introduced several new features, including inline functions, several new data types (including long long int and a complex type to represent complex numbers), variable-length arrays and flexible array members, improved support for IEEE 754 floating point, support for variadic macros (macros of variable arity), and support for one-line comments beginning with //, as in BCPL or C++. Many of these had already been implemented as extensions in several C compilers.

C99 is for the most part backward compatible with C90, but is stricter in some ways; in particular, a declaration that lacks a type specifier no longer has int implicitly assumed. A standard macro __STDC_VERSION__ is defined with value 199901L to indicate that C99 support is available. GCC, Solaris Studio, and other C compilers now support many or all of the new features of C99. The C compiler in Microsoft Visual C++, however, implements the C89 standard and those parts of C99 that are required for compatibility with C++11.[17]

C11

In 2007, work began on another revision of the C standard, informally called "C1X" until its official publication on 2011-12-08. The C standards committee adopted guidelines to limit the adoption of new features that had not been tested by existing implementations.

The C11 standard adds numerous new features to C and the library, including type generic macros, anonymous structures, improved Unicode support, atomic operations, multi-threading, and bounds-checked functions. It also makes some portions of the existing C99 library optional, and improves compatibility with C++. The standard macro __STDC_VERSION__ is defined as 201112L to indicate that C11 support is available.

Embedded C

Historically, embedded C programming requires nonstandard extensions to the C language in order to support exotic features such as fixed-point arithmetic, multiple distinct memory banks, and basic I/O operations.

In 2008, the C Standards Committee published a technical report extending the C language[18] to address these issues by providing a common standard for all implementations to adhere to. It includes a number of features not available in normal C, such as fixed-point arithmetic, named address spaces, and basic I/O hardware addressing.

Syntax

C has a formal grammar specified by the C standard.[19] Line endings are generally not significant in C; however, line boundaries do have significance during the preprocessing phase. Comments may appear either between the delimiters /* and */, or (since C99) following // until the end of the line. Comments delimited by /* and */ do not nest, and these sequences of characters are not interpreted as comment delimiters if they appear inside string or character literals.[20]

C source files contain declarations and function definitions. Function definitions, in turn, contain declarations and statements. Declarations either define new types using keywords such as struct, union, and enum, or assign types to and perhaps reserve storage for new variables, usually by writing the type followed by the variable name. Keywords such as char and int specify built-in types. Sections of code are enclosed in braces ({ and }, sometimes called "curly brackets") to limit the scope of declarations and to act as a single statement for control structures.

As an imperative language, C uses statements to specify actions. The most common statement is an expression statement, consisting of an expression to be evaluated, followed by a semicolon; as a side effect of the evaluation, functions may be called and variables may be assigned new values. To modify the normal sequential execution of statements, C provides several control-flow statements identified by reserved keywords. Structured programming is supported by if(-else) conditional execution and by do-while, while, and for iterative execution (looping). The for statement has separate initialization, testing, and reinitialization expressions, any or all of which can be omitted. break and continue can be used to leave the innermost enclosing loop statement or skip to its reinitialization. There is also a non-structured goto statement which branches directly to the designated label within the function. switch selects a case to be executed based on the value of an integer expression.

Expressions can use a variety of built-in operators and may contain function calls. The order in which arguments to functions and operands to most operators are evaluated is unspecified. The evaluations may even be interleaved. However, all side effects (including storage to variables) will occur before the next "sequence point"; sequence points include the end of each expression statement, and the entry to and return from each function call. Sequence points also occur during evaluation of expressions containing certain operators (&&, ||, ?: and the comma operator). This permits a high degree of object code optimization by the compiler, but requires C programmers to take more care to obtain reliable results than is needed for other programming languages.

Kernighan and Ritchie say in the Introduction of The C Programming Language: "C, like any other language, has its blemishes. Some of the operators have the wrong precedence; some parts of the syntax could be better."[21] The C standard did not attempt to correct many of these blemishes, because of the impact of such changes on already existing software.

Character set

The basic C source character set includes the following characters:

- Lowercase and uppercase letters of ISO Basic Latin Alphabet:

a–zA–Z - Decimal digits:

0–9 - Graphic characters:

! " # % & ' ( ) * + , - . / : ; < = > ? [ \ ] ^ _ { | } ~ - Whitespace characters: space, horizontal tab, vertical tab, form feed, newline

Newline indicates the end of a text line; it need not correspond to an actual single character, although for convenience C treats it as one.

Additional multi-byte encoded characters may be used in string literals, but they are not entirely portable. The latest C standard (C11) allows multi-national Unicode characters to be embedded portably within C source text by using \uXXXX or \UXXXXXXXX encoding (where the X denotes a hexadecimal character), although this feature is not yet widely implemented.

The basic C execution character set contains the same characters, along with representations for alert, backspace, and carriage return. Run-time support for extended character sets has increased with each revision of the C standard.

Reserved words

C89 has 32 reserved words, also known as keywords, which are the words that cannot be used for any purposes other than those for which they are predefined:

|

C99 reserved five more words:

C11 reserved seven more words:[22]

|

|

|

|

Most of the recently reserved words begin with an underscore followed by a capital letter, because identifiers of that form were previously reserved by the C standard for use only by implementations. Since existing program source code should not have been using these identifiers, it would not be affected when C implementations started supporting these extensions to the programming language. Some standard headers do define more convenient synonyms for underscored identifiers. The language previously included a reserved word called entry, but this was seldom implemented, and has now been removed as a reserved word.[23]

Operators

C supports a rich set of operators, which are symbols used within an expression to specify the manipulations to be performed while evaluating that expression. C has operators for:

- arithmetic:

+,-,*,/,% - assignment:

= - augmented assignment:

+=,-=,*=,/=,%=,&=,|=,^=,<<=,>>= - bitwise logic:

~,&,|,^ - bitwise shifts:

<<,>> - boolean logic:

!,&&,|| - conditional evaluation:

? : - equality testing:

==,!= - calling functions:

( ) - increment and decrement:

++,-- - member selection:

.,-> - object size:

sizeof - order relations:

<,<=,>,>= - reference and dereference:

&,*,[ ] - sequencing:

, - subexpression grouping:

( ) - type conversion:

(typename)

C uses the operator = (used in mathematics to express equality) to indicate assignment, following the precedent of Fortran and PL/I, but unlike ALGOL and its derivatives. C uses the operator == to test for equality. The similarity between these two operators (assignment and equality) may result in the accidental use of one in place of the other, and in many cases, the mistake does not produce an error message (although some compilers produce warnings). For example, the conditional expression if(a==b+1) might mistakenly be written as if(a=b+1), which will be evaluated as true if a is not zero after the assignment.[24]

The C operator precedence is not always intuitive. For example, the operator == binds more tightly than (is executed prior to) the operators & (bitwise AND) and | (bitwise OR) in expressions such as x & 1 == 0, which must be written as (x & 1) == 0 if that is the coder's intent.[25]

"Hello, world" example

The "hello, world" example, which appeared in the first edition of K&R, has become the model for an introductory program in most programming textbooks, regardless of programming language. The program prints "hello, world" to the standard output, which is usually a terminal or screen display.

The original version was:[26]

main()

{

printf("hello, world\n");

}

A standard-conforming "hello, world" program is:[lower-alpha 1]

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("hello, world\n");

}

The first line of the program contains a preprocessing directive, indicated by #include. This causes the compiler to replace that line with the entire text of the stdio.h standard header, which contains declarations for standard input and output functions such as printf. The angle brackets surrounding stdio.h indicate that stdio.h is located using a search strategy that prefers headers provided with the compiler to other headers having the same name, as opposed to double quotes which typically include local or project-specific header files.

The next line indicates that a function named main is being defined. The main function serves a special purpose in C programs; the run-time environment calls the main function to begin program execution. The type specifier int indicates that the value that is returned to the invoker (in this case the run-time environment) as a result of evaluating the main function, is an integer. The keyword void as a parameter list indicates that this function takes no arguments.[lower-alpha 2]

The opening curly brace indicates the beginning of the definition of the main function.

The next line calls (diverts execution to) a function named printf, which in this case is supplied from a system library. In this call, the printf function is passed (provided with) a single argument, the address of the first character in the string literal "hello, world\n". The string literal is an unnamed array with elements of type char, set up automatically by the compiler with a final 0-valued character to mark the end of the array (printf needs to know this). The \n is an escape sequence that C translates to a newline character, which on output signifies the end of the current line. The return value of the printf function is of type int, but it is silently discarded since it is not used. (A more careful program might test the return value to determine whether or not the printf function succeeded.) The semicolon ; terminates the statement.

The closing curly brace indicates the end of the code for the main function. According to the C99 specification and newer, the main function, unlike any other function, will implicitly return a value of 0 upon reaching the } that terminates the function. This is interpreted by the run-time system as an exit code indicating successful execution.[27]

Data types

The type system in C is static and weakly typed, which makes it similar to the type system of ALGOL descendants such as Pascal.[28] There are built-in types for integers of various sizes, both signed and unsigned, floating-point numbers, and enumerated types (enum). Integer type char is often used for single-byte characters. C99 added a boolean datatype. There are also derived types including arrays, pointers, records (struct), and untagged unions (union).

C is often used in low-level systems programming where escapes from the type system may be necessary. The compiler attempts to ensure type correctness of most expressions, but the programmer can override the checks in various ways, either by using a type cast to explicitly convert a value from one type to another, or by using pointers or unions to reinterpret the underlying bits of a data object in some other way.

Some find C's declaration syntax unintuitive, particularly for function pointers. (Ritchie's idea was to declare identifiers in contexts resembling their use: "declaration reflects use".)[29]

C's usual arithmetic conversions allow for efficient code to be generated, but can sometimes produce unexpected results. For example, a comparison of signed and unsigned integers of equal width requires a conversion of the signed value to unsigned. This can generate unexpected results if the signed value is negative.

Pointers

C supports the use of pointers, a type of reference that records the address or location of an object or function in memory. Pointers can be dereferenced to access data stored at the address pointed to, or to invoke a pointed-to function. Pointers can be manipulated using assignment or pointer arithmetic. The run-time representation of a pointer value is typically a raw memory address (perhaps augmented by an offset-within-word field), but since a pointer's type includes the type of the thing pointed to, expressions including pointers can be type-checked at compile time. Pointer arithmetic is automatically scaled by the size of the pointed-to data type. Pointers are used for many purposes in C. Text strings are commonly manipulated using pointers into arrays of characters. Dynamic memory allocation is performed using pointers. Many data types, such as trees, are commonly implemented as dynamically allocated struct objects linked together using pointers. Pointers to functions are useful for passing functions as arguments to higher-order functions (such as qsort or bsearch) or as callbacks to be invoked by event handlers.[27]

A null pointer value explicitly points to no valid location. Dereferencing a null pointer value is undefined, often resulting in a segmentation fault. Null pointer values are useful for indicating special cases such as no "next" pointer in the final node of a linked list, or as an error indication from functions returning pointers. In appropriate contexts in source code, such as for assigning to a pointer variable, a null pointer constant can be written as 0, with or without explicit casting to a pointer type, or as the NULL macro defined by several standard headers. In conditional contexts, null pointer values evaluate to false, while all other pointer values evaluate to true.

Void pointers (void *) point to objects of unspecified type, and can therefore be used as "generic" data pointers. Since the size and type of the pointed-to object is not known, void pointers cannot be dereferenced, nor is pointer arithmetic on them allowed, although they can easily be (and in many contexts implicitly are) converted to and from any other object pointer type.[27]

Careless use of pointers is potentially dangerous. Because they are typically unchecked, a pointer variable can be made to point to any arbitrary location, which can cause undesirable effects. Although properly used pointers point to safe places, they can be made to point to unsafe places by using invalid pointer arithmetic; the objects they point to may continue to be used after deallocation (dangling pointers); they may be used without having been initialized (wild pointers); or they may be directly assigned an unsafe value using a cast, union, or through another corrupt pointer. In general, C is permissive in allowing manipulation of and conversion between pointer types, although compilers typically provide options for various levels of checking. Some other programming languages address these problems by using more restrictive reference types.

Arrays

Array types in C are traditionally of a fixed, static size specified at compile time. (The more recent C99 standard also allows a form of variable-length arrays.) However, it is also possible to allocate a block of memory (of arbitrary size) at run-time, using the standard library's malloc function, and treat it as an array. C's unification of arrays and pointers means that declared arrays and these dynamically allocated simulated arrays are virtually interchangeable.

Since arrays are always accessed (in effect) via pointers, array accesses are typically not checked against the underlying array size, although some compilers may provide bounds checking as an option.[30] Array bounds violations are therefore possible and rather common in carelessly written code, and can lead to various repercussions, including illegal memory accesses, corruption of data, buffer overruns, and run-time exceptions. If bounds checking is desired, it must be done manually.

C does not have a special provision for declaring multi-dimensional arrays, but rather relies on recursion within the type system to declare arrays of arrays, which effectively accomplishes the same thing. The index values of the resulting "multi-dimensional array" can be thought of as increasing in row-major order.

Multi-dimensional arrays are commonly used in numerical algorithms (mainly from applied linear algebra) to store matrices. The structure of the C array is well suited to this particular task. However, since arrays are passed merely as pointers, the bounds of the array must be known fixed values or else explicitly passed to any subroutine that requires them, and dynamically sized arrays of arrays cannot be accessed using double indexing. (A workaround for this is to allocate the array with an additional "row vector" of pointers to the columns.)

C99 introduced "variable-length arrays" which address some, but not all, of the issues with ordinary C arrays.

Array–pointer interchangeability

The subscript notation x[i] (where x designates a pointer) is syntactic sugar for *(x+i).[31] Taking advantage of the compiler's knowledge of the pointer type, the address that x + i points to is not the base address (pointed to by x) incremented by i bytes, but rather is defined to be the base address incremented by i multiplied by the size of an element that x points to. Thus, x[i] designates the i+1th element of the array.

Furthermore, in most expression contexts (a notable exception is as operand of sizeof), the name of an array is automatically converted to a pointer to the array's first element. This implies that an array is never copied as a whole when named as an argument to a function, but rather only the address of its first element is passed. Therefore, although function calls in C use pass-by-value semantics, arrays are in effect passed by reference.

The size of an element can be determined by applying the operator sizeof to any dereferenced element of x, as in n = sizeof *x or n = sizeof x[0], and the number of elements in a declared array A can be determined as sizeof A / sizeof A[0]. The latter only applies to array names: variables declared with subscripts (int A[20]). Due to the semantics of C, it is not possible to determine the entire size of arrays through pointers to arrays or those created by dynamic allocation (malloc); code such as sizeof arr / sizeof arr[0] (where arr designates a pointer) will not work since the compiler assumes the size of the pointer itself is being requested.[32][33] Since array name arguments to sizeof are not converted to pointers, they do not exhibit such ambiguity. However, arrays created by dynamic allocation are accessed by pointers rather than true array variables, so they suffer from the same sizeof issues as array pointers.

Thus, despite this apparent equivalence between array and pointer variables, there is still a distinction to be made between them. Even though the name of an array is, in most expression contexts, converted into a pointer (to its first element), this pointer does not itself occupy any storage; the array name is not an l-value, and its address is a constant, unlike a pointer variable. Consequently, what an array "points to" cannot be changed, and it is impossible to assign a new address to an array name. Array contents may be copied, however, by using the memcpy function, or by accessing the individual elements.

Memory management

One of the most important functions of a programming language is to provide facilities for managing memory and the objects that are stored in memory. C provides three distinct ways to allocate memory for objects:[27]

- Static memory allocation: space for the object is provided in the binary at compile-time; these objects have an extent (or lifetime) as long as the binary which contains them is loaded into memory.

- Automatic memory allocation: temporary objects can be stored on the stack, and this space is automatically freed and reusable after the block in which they are declared is exited.

- Dynamic memory allocation: blocks of memory of arbitrary size can be requested at run-time using library functions such as

mallocfrom a region of memory called the heap; these blocks persist until subsequently freed for reuse by calling the library functionreallocorfree

These three approaches are appropriate in different situations and have various trade-offs. For example, static memory allocation has little allocation overhead, automatic allocation may involve slightly more overhead, and dynamic memory allocation can potentially have a great deal of overhead for both allocation and deallocation. The persistent nature of static objects is useful for maintaining state information across function calls, automatic allocation is easy to use but stack space is typically much more limited and transient than either static memory or heap space, and dynamic memory allocation allows convenient allocation of objects whose size is known only at run-time. Most C programs make extensive use of all three.

Where possible, automatic or static allocation is usually simplest because the storage is managed by the compiler, freeing the programmer of the potentially error-prone chore of manually allocating and releasing storage. However, many data structures can change in size at runtime, and since static allocations (and automatic allocations before C99) must have a fixed size at compile-time, there are many situations in which dynamic allocation is necessary.[27] Prior to the C99 standard, variable-sized arrays were a common example of this. (See the article on malloc for an example of dynamically allocated arrays.) Unlike automatic allocation, which can fail at run time with uncontrolled consequences, the dynamic allocation functions return an indication (in the form of a null pointer value) when the required storage cannot be allocated. (Static allocation that is too large is usually detected by the linker or loader, before the program can even begin execution.)

Unless otherwise specified, static objects contain zero or null pointer values upon program startup. Automatically and dynamically allocated objects are initialized only if an initial value is explicitly specified; otherwise they initially have indeterminate values (typically, whatever bit pattern happens to be present in the storage, which might not even represent a valid value for that type). If the program attempts to access an uninitialized value, the results are undefined. Many modern compilers try to detect and warn about this problem, but both false positives and false negatives can occur.

Another issue is that heap memory allocation has to be synchronized with its actual usage in any program in order for it to be reused as much as possible. For example, if the only pointer to a heap memory allocation goes out of scope or has its value overwritten before free() is called, then that memory cannot be recovered for later reuse and is essentially lost to the program, a phenomenon known as a memory leak. Conversely, it is possible for memory to be freed but continue to be referenced, leading to unpredictable results. Typically, the symptoms will appear in a portion of the program far removed from the actual error, making it difficult to track down the problem. (Such issues are ameliorated in languages with automatic garbage collection.)

Libraries

The C programming language uses libraries as its primary method of extension. In C, a library is a set of functions contained within a single "archive" file. Each library typically has a header file, which contains the prototypes of the functions contained within the library that may be used by a program, and declarations of special data types and macro symbols used with these functions. In order for a program to use a library, it must include the library's header file, and the library must be linked with the program, which in many cases requires compiler flags (e.g., -lm, shorthand for "link the math library").[27]

The most common C library is the C standard library, which is specified by the ISO and ANSI C standards and comes with every C implementation (implementations which target limited environments such as embedded systems may provide only a subset of the standard library). This library supports stream input and output, memory allocation, mathematics, character strings, and time values. Several separate standard headers (for example, stdio.h) specify the interfaces for these and other standard library facilities.

Another common set of C library functions are those used by applications specifically targeted for Unix and Unix-like systems, especially functions which provide an interface to the kernel. These functions are detailed in various standards such as POSIX and the Single UNIX Specification.

Since many programs have been written in C, there are a wide variety of other libraries available. Libraries are often written in C because C compilers generate efficient object code; programmers then create interfaces to the library so that the routines can be used from higher-level languages like Java, Perl, and Python.[27]

Language tools

A number of tools have been developed to help C programmers find and fix statements with undefined behavior or possibly erroneous expressions, with greater rigor than that provided by the compiler. The tool lint was the first such, leading to many others.

Automated source code checking and auditing are beneficial in any language, and for C many such tools exist, such as Lint. A common practice is to use Lint to detect questionable code when a program is first written. Once a program passes Lint, it is then compiled using the C compiler. Also, many compilers can optionally warn about syntactically valid constructs that are likely to actually be errors. MISRA C is a proprietary set of guidelines to avoid such questionable code, developed for embedded systems.[34]

There are also compilers, libraries, and operating system level mechanisms for performing actions that are not a standard part of C, such as bounds checking for arrays, detection of buffer overflow, serialization, dynamic memory tracking, and automatic garbage collection.

Tools such as Purify or Valgrind and linking with libraries containing special versions of the memory allocation functions can help uncover runtime errors in memory usage.

Uses

C is widely used for "system programming", including implementing operating systems and embedded system applications, because C code, when written for portability, can be used for most purposes, yet when needed, system-specific code can be used to access specific hardware addresses and to perform type punning to match externally imposed interface requirements, with a low run-time demand on system resources. C can also be used for website programming using CGI as a "gateway" for information between the Web application, the server, and the browser.[36] C is often chosen over interpreted languages because of its speed, stability, and near-universal availability.[37]

One consequence of C's wide availability and efficiency is that compilers, libraries and interpreters of other programming languages are often implemented in C. The primary implementations of Python, Perl 5 and PHP, for example, are all written in C.

Because the layer of abstraction is thin and the overhead is low, C enables programmers to create efficient implementations of algorithms and data structures, useful for computationally intense programs. For example, the GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library, the GNU Scientific Library, Mathematica, and MATLAB are completely or partially written in C.

C is sometimes used as an intermediate language by implementations of other languages. This approach may be used for portability or convenience; by using C as an intermediate language, additional machine-specific code generators are not necessary. C has some features, such as line-number preprocessor directives and optional superfluous commas at the end of initializer lists, that support compilation of generated code. However, some of C's shortcomings have prompted the development of other C-based languages specifically designed for use as intermediate languages, such as C--.

C has also been widely used to implement end-user applications. However, such applications can also be written in newer, higher-level languages.

Related languages

C has directly or indirectly influenced many later languages such as C#, D, Go, Java, JavaScript, Limbo, LPC, Perl, PHP, Python, and Unix's C shell. The most pervasive influence has been syntactical: all of the languages mentioned combine the statement and (more or less recognizably) expression syntax of C with type systems, data models and/or large-scale program structures that differ from those of C, sometimes radically.

Several C or near-C interpreters exist, including Ch and CINT, which can also be used for scripting.

When object-oriented languages became popular, C++ and Objective-C were two different extensions of C that provided object-oriented capabilities. Both languages were originally implemented as source-to-source compilers; source code was translated into C, and then compiled with a C compiler.

The C++ programming language was devised by Bjarne Stroustrup as an approach to providing object-oriented functionality with a C-like syntax.[38] C++ adds greater typing strength, scoping, and other tools useful in object-oriented programming, and permits generic programming via templates. Nearly a superset of C, C++ now supports most of C, with a few exceptions.

Objective-C was originally a very "thin" layer on top of C, and remains a strict superset of C that permits object-oriented programming using a hybrid dynamic/static typing paradigm. Objective-C derives its syntax from both C and Smalltalk: syntax that involves preprocessing, expressions, function declarations, and function calls is inherited from C, while the syntax for object-oriented features was originally taken from Smalltalk.

In addition to C++ and Objective-C, Ch, Cilk and Unified Parallel C are nearly supersets of C.

See also

- Comparison of Pascal and C

- Comparison of programming languages

- International Obfuscated C Code Contest

- List of C-based programming languages

- List of C compilers

Notes

- ↑ The original example code will compile on most modern compilers that are not in strict standard compliance mode, but it does not fully conform to the requirements of either C89 or C99. In fact, C99 requires that a diagnostic message be produced.

- ↑ The

mainfunction actually has two arguments,int argcandchar *argv[], respectively, which can be used to handle command line arguments. The ISO C standard (section 5.1.2.2.1) requires both forms ofmainto be supported, which is special treatment not afforded to any other function.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (February 1978). The C Programming Language (1st ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-110163-3. Regarded by many to be the authoritative reference on C.

- ↑ Ritchie (1993): "Thompson had made a brief attempt to produce a system coded in an early version of C—before structures—in 1972, but gave up the effort."

- ↑ Ritchie (1993): "The scheme of type composition adopted by C owes considerable debt to Algol 68, although it did not, perhaps, emerge in a form that Algol's adherents would approve of."

- 1 2 "Verilog HDL (and C)" (PDF). The Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University. 2010-06-03. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

1980s: ; Verilog first introduced ; Verilog inspired by the C programming language

- ↑ Ritchie (1993)

- ↑ Lawlis, Patricia K. (August 1997). "Guidelines for Choosing a Computer Language: Support for the Visionary Organization". Ada Information Clearinghouse. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

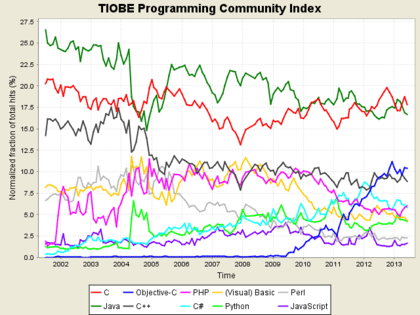

- ↑ "Programming Language Popularity". 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ↑ "TIOBE Programming Community Index". 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ↑ Ritchie, Dennis M. (March 1993). "The Development of the C Language". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 28 (3): 201–208. doi:10.1145/155360.155580.

- ↑ Ulf Bilting & Jan Skansholm "Vägen till C" (Swedish) meaning "The Road to C", third edition, Studentlitteratur, year 2000, page 3. ISBN 91-44-01468-6.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, S. C.; Ritchie, D. M. (1978). "Portability of C Programs and the UNIX System". Bell System Tech. J. 57 (6): 2021–2048. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1978.tb02141.x. Retrieved 16 December 2012. (Note: this reference is an OCR scan of the original, and contains an OCR glitch rendering "IBM 370" as "IBM 310".)

- ↑ McIlroy, M. D. (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer's Manual, 1971–1986 (PDF) (Technical report). CSTR. Bell Labs. p. 10. 139.

- ↑ Stallings, William. "Operating Systems: Internals and Design Principles" 5th ed, page 91. Pearson Education, Inc. 2005.

- 1 2 Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (March 1988). The C Programming Language (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-110362-8.

- ↑ Stroustrup, Bjarne (2002). Sibling rivalry: C and C++ (PDF) (Report). AT&T Labs.

- ↑ "JTC1/SC22/WG14 – C". Home page. ISO/IEC. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ Andrew Binstock (October 12, 2011). "Interview with Herb Sutter". Dr. Dobbs. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ↑ "TR 18037: Embedded C" (PDF). ISO / IEC. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Harbison, Samuel P.; Steele, Guy L. (2002). C: A Reference Manual (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-089592-X. Contains a BNF grammar for C.

- ↑ Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1996). The C Programming Language (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 192. ISBN 7 302 02412 X.

- ↑ Page 3 of the original K&R[1]

- ↑ ISO/IEC 9899:201x (ISO C11) Committee Draft

- ↑ Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1996). The C Programming Language (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 192, 259. ISBN 7 302 02412 X.

- ↑ "10 Common Programming Mistakes in C++". Cs.ucr.edu. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ↑ Schultz, Thomas (2004). C and the 8051 (3rd ed.). Otsego, MI: PageFree Publishing Inc. p. 20. ISBN 1-58961-237-X. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ Page 6 of the original K&R[1]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Klemens, Ben (2013). 21st Century C. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 1-4493-2714-1.

- ↑ Feuer, Alan R.; Gehani, Narain H. (March 1982). "Comparison of the Programming Languages C and Pascal". ACM Computing Surveys. 14 (1): 73–92. doi:10.1145/356869.356872. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Page 122 of K&R2[14]

- ↑ For example, gcc provides _FORTIFY_SOURCE. "Security Features: Compile Time Buffer Checks (FORTIFY_SOURCE)". fedoraproject.org. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric S. (11 October 1996). The New Hacker's Dictionary (3rd ed.). MIT Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-262-68092-9. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Summit, Steve. "comp.lang.c Frequently Asked Questions 6.23". Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ Summit, Steve. "comp.lang.c Frequently Asked Questions 7.28". Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Man Page for lint (freebsd Section 1)". unix.com. 2001-05-24. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ McMillan, Robert (2013-08-01). "Is Java Losing Its Mojo?". Wired.

- ↑ Dr. Dobb's Sourcebook. U.S.A.: Miller Freeman, Inc. November–December 1995.

- ↑ "Using C for CGI Programming". linuxjournal.com. 1 March 2005. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Stroustrup, Bjarne (1993). "A History of C++: 1979−1991" (PDF). Retrieved 9 June 2011.

Sources

- Ritchie, Dennis M. (1993). The Development of the C Language. The second ACM SIGPLAN History of Programming Languages Conference (HOPL-II). Cambridge, MA, USA — April 20–23, 1993: ACM. pp. 201–208. doi:10.1145/154766.155580. ISBN 0-89791-570-4. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

Further reading

- Banahan, M.; Brady, D.; Doran, M. (1991). The C Book (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- King, K. N. (April 2008). C Programming: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.). Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97950-3.

- Thompson, Ken. "A New C Compiler" (PDF). Murray Hill, New Jersey: AT&T Bell Laboratories.

- Feuer, Alan R. (1998). The C Puzzle Book (1st, revised printing ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-60461-0.

External links

- ISO C Working Group official website

- comp.lang.c Frequently Asked Questions

- ISO/IEC 9899, publicly available official C documents, including the C99 Rationale

- "C99 with Technical corrigenda TC1, TC2, and TC3 included" (PDF). (3.61 MB)

- A History of C, by Dennis Richie