Calico

Calico (in British usage, 1505,[1] AmE "muslin") is a plain-woven textile made from unbleached and often not fully processed cotton. It may contain unseparated husk parts, for example. The fabric is less coarse and thick than canvas or denim, but it is still very cheap owing to its unfinished and undyed appearance.

The fabric was originally from the city of Kozhikode (known by the English as Calicut) in southwestern India. It was made by the traditional weavers called cāliyans. The raw fabric was dyed and printed in bright hues, and calico prints became popular in Europe.

History

Calico originated in Kozhikode (also known as Calicut, from which the name of the textile came) in southwestern India (in present-day Kerala) during the 11th century.[2] The cloth was known as "cāliyan" to the natives.[3]

It was mentioned in Indian literature by the 12th century when the writer Hēmacandra described calico fabric prints with a lotus design.[2] By the 15th century calico from Gujǎrāt made its appearance in Egypt.[2] Trade with Europe followed from the 17th century onwards.[2]

Calico was woven using Sūrat cotton for both the warp and weft.

Politics of cotton

In the 18th century, England was famous for its woollen and worsted cloth. That industry, centred in the east and south in towns such as Norwich, jealously protected their product. Cotton processing was tiny: in 1701 only 1,985,868 pounds (900,775 kg) of cottonwool was imported into England, and by 1730 this had fallen to 1,545,472 pounds (701,014 kg). This was due to commercial legislation to protect the woollen industry.[4] Cheap calico prints, imported by the East India Company from Hindustān (India), had become popular. In 1700 an Act of Parliament passed to prevent the importation of dyed or printed calicoes from India, China or Persia. This caused demand to switch to imported grey cloth instead—calico that had not been finished—dyed or printed. These were printed with popular patterns in southern England. Also, Lancashire businessmen produced grey cloth with linen warp and cotton weft, known as fustian, which they sent to London for finishing.[4] Cottonwool imports recovered though, and by 1720 were almost back to their 1701 levels. Again the woolen manufacturers, in true protectionist fashion, claimed that the imports were taking jobs away from workers in Coventry.[5] A new law passed, enacting fines against anyone caught wearing printed or stained calico muslins. Neckcloths and fustians were exempted. The Lancashire manufacturers exploited this exemption; coloured cotton weft with linen warp were specifically permitted by the 1736 Manchester Act. There now was an artificial demand for woven cloth.

In 1764, 3,870,392 pounds (1,755,580 kg) of cotton-wool were imported.[6] It has been noted that this change in consumer demand a key part of the process that brought the Indian economy from sophisticated textile production to supply of raw materials. These events occurred under colonial rule and were described by Nehru and also some more recent scholars as "de-industrialization."[7]

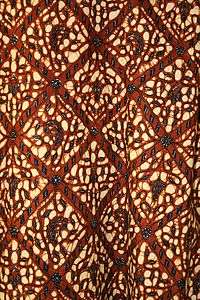

Calico printing

Early Indian chintz, that is, glazed calico with a large floral pattern. were primarily produced by painting techniques.[8] Later, the hues were applied by wooden blocks, and the cloth manufacturers in Britain printing calico used wooden block printing. Confusingly, linen and silk printed this way were known as linen calicoes and silk calicoes. Early European calicoes (1680) would be cheap plain-weave white cotton fabric with equal weft and warp plain weave cotton fabric in, or cream or unbleached cotton, with a design block-printed using a single alizarin dye fixed with two mordants, giving a red and black pattern. Polychromatic prints were possible, using two sets of blocks and an additional blue dye. The Indian taste was for dark printed backgrounds while the European market preferred a pattern on a cream base. As the century progressed the European preference moved from the large chintz patterns to smaller, tighter patterns.[9]

Thomas Bell patented a printing technique in 1783 that used copper rollers, and Livesey, Hargreaves and Company put the first machine that used it into operation near Preston, Lancashire in 1785. The production volume for printed cloth in Lancashire in 1750 was estimated at 50,000 pieces of 30 yards (27 m) In 1850 it was 20,000,000 pieces.[8] After 1888, block printing was only used for short-run specialized jobs. After 1880, profits from printing fell due to overcapacity and the firms started to form combines. In the first, three Scottish firms formed the United Turkey Red Co. Ltd in 1897, and the second, in 1899, was the much larger Calico Printers' Association 46 printing concerns and 13 merchants combined, representing 85% of the British printing capacity. Some of this capacity was removed and in 1901 Calico had 48% of the printing trade. In 1916, they and the other printers formed and joined a trade association, which then set minimum prices for each 'price section' of the industry.

The trade association remained in operation until 1954, when the arrangement was challenged by the government Monopolies Commission. Over the intervening period much trade had been lost overseas.[10]

Terminology

In the UK, Australia and New Zealand:

- Calico – simple, cheap equal weft and warp plain weave fabric in white, cream or unbleached cotton.

- Muslin – a very fine, light plain weave cotton fabric.

- Muslin gauze – muslin.

- Gauze – extremely soft and fine cotton fabric with a very open plain weave.

- Cheesecloth – gauze.

In the US:

- Calico – cotton fabric with a small, all-over floral print[11]

- Muslin – simple, cheap equal weft and warp plain weave fabric in white, cream or unbleached cotton and/or a very fine, light plain weave cotton fabric (sometimes called muslin gauze).

- Muslin gauze – the very lightest, most open weave of muslin.

- Gauze – any very light fabric, generally with a plain weave

- Cheesecloth – extremely soft and fine cotton fabric with a very open plain weave.

Printed calico was imported into the United States from Lancashire in the 1780s, and here a linguistic separation occurred, while Europe maintained the word calico for the fabric, in the States it was used to refer to the printed design.[9]

These colorful, small-patterned printed fabrics gave rise to the use of the word calico to describe a cat coat color: "calico cat". The patterned fabric also gave its name to two species of North American crabs; see the calico crab.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Lynda Mugglestone "The Oxford History of English". Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). calico

- ↑ Condra, Jill. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History: 1801 to the Present. 3.

- 1 2 Espinasse 1874, p. 296

- ↑ Espinasse 1874, p. 298

- ↑ Espinasse 1874, p. 299

- ↑ "India's De-Industrialization Under British Rule: New Ideas, New Evidence David Clingingsmith and Jeffrey G. Williamson NBER Working Paper No. 10586 June 2004 JEL No. F1, N7, O2" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- 1 2 Turnbull, A History of Calico Printing in Great Britain, 1951.

- 1 2 3 Calico, muslin, gauze – terminology

- ↑ Hughes, William (1954-04-13). Report on the Process of Calico Printing. House of Commons, London: Monopolies and Restrictive Practices Commission. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ Kadolph, Sara J., ed. (2007) Textiles, 10th ed., p. 463, Pearson/Prentice-Hall ISBN 0-13-118769-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calico. |

- Espinasse, Francis (1874). Lancashire Worthies. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). "Calico". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). "Calico". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.- Charles O'Neill (1869) A dictionary of dyeing and calico printing - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- William Crookes (1874) A practical handbook of dyeing and calico-printing. Illustrated with period fabric swatches. - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

.svg.png)