Canal Age

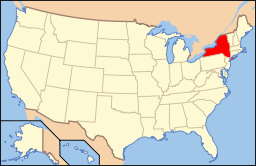

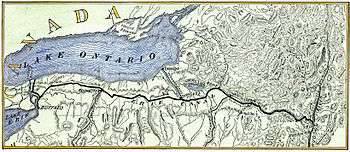

| Erie Canal | |

|---|---|

|

Current Route of the Erie Canal | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 524 miles (843 km) |

| Locks | 36 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 571 ft (174 m) |

| Status | open |

| Navigation authority | New York State Canal Corporation |

| History | |

| Original owner | New York State |

| Principal engineer | Benjamin Wright |

| Other engineer(s) | Canvass White, Amos Eaton |

| Construction began | July 4, 1817 (at Rome, New York) |

| Date of first use | May 17, 1821 |

| Date completed | October 26, 1825 |

| Date restored | September 3, 1999 |

| Geography | |

| Start point |

Hudson river near Albany, New York (42°47′00″N 73°40′36″W / 42.7834°N 73.6767°W) |

| End point |

Niagara river near Buffalo, New York (43°01′25″N 78°53′24″W / 43.0237°N 78.8901°W) |

| Branch(es) | Oswego Canal, Cayuga–Seneca Canal |

| Branch of | New York State Canal System |

| Connects to | Champlain Canal, Welland Canal |

The Canal Age is a term of art used by historians of Science, Technology, and Industry. The Canal eras in various parts of the world have varied in the world timeline, in the main, by civilizations (Egypt, Ancient Babylon), dynastic Empires of India, China, and Southeast Asia, and of European mercantilism. Canals are culturally dependent, and culture creating, part of industry, and industry creating and until the coming into an era when steam locomotives generated refined speeds and sufficient power, the canal was by far the fastest way to travel long distances quickly, for commercial canals generally had boatmen shifts that kept the barges moving behind mule teams 24 hours a day.[lower-alpha 1] Like many North American canals of the 1820s-1840s, the canal operating companies partnered with or founded short feeder railroads as were necessary appendages to connect to their sources or markets. Two good examples of this were funded by private enterprise:

- The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company used vertically integrated mining raw materials, transporting them, manufacturing with them, and merchandising by building coal mines, the instrumental Lehigh Canal, and feeding their own iron goods manufacturing industries and assuaging the American Republics first energy crisis by increasing coal production from 1820 onwards using the nations second constructed railway, the Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad.

- The second coal road and canal system was inspired by LC&N's success. The Delaware and Hudson Canal and Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad. The LC&N operation was aimed at supplying the countries premier city, Philadelphia with much needed fuel. The D&H companies were founded purposefully to supply the explosively growing city of New York's energy needs.

Together, they and the Schuylkill Canal-Reading Railroad would supply and transport the majority of Anthracite needed by northern industries in the early North American Industrial Revolution. Unlike Europe, America did not have canals for several hundred years before industrialization. In North America, everything grew up together all at the same times.

Early railroads in North America made many canals economically feasible, and canal's needs added to the demands by industries that pushed the early railroads into pressurized research and development and rapid steady improvements.

|

Lehigh Canal | |

|

The Lehigh Canal as seen from Guard Lock 8 & Lockhouse, Island Park Road, Glendon, Northampton County, PA | |

|

Lower division of the Lehigh Canal, from Jim Thorpe, PA to Easton, PA | |

| Location |

Lehigh River Upper: Nesquehoning, PA to White Haven, PA Lower: Mauch Chunk (Jim Thorpe) to Delaware River at Easton, PA |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°46′09″N 75°36′13″W / 40.76917°N 75.60361°WCoordinates: 40°46′09″N 75°36′13″W / 40.76917°N 75.60361°W |

| Built |

1818-1821; 24-27 upper: 1838-1843, Upper ruined & abandoned: 1862 |

| Architect | Canvass White, Josiah White |

| Architectural style | Fitted stone, iron and wood |

| NRHP Reference # | 78002437, 78002439, 79002179, 79002307, 80003553[1] |

| Added to NRHP | Earliest October 2, 1978 |

North American Canal Age

| Erie Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Technology Archaeologists and Industrial Historians date the American Canal Age from 1790 to [2]

Background

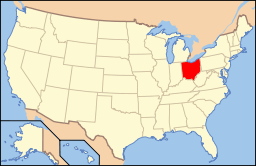

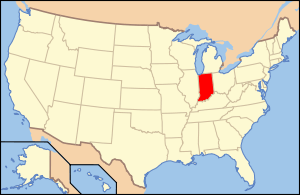

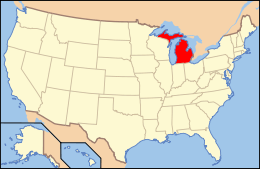

From the first days of the expansion of the British colonies from the coast of North America into the heartland of the continent, a recurring problem was that of transportation between the coastal ports and the interior. This was not unique to the Americas, and the problem still exists in those parts of the world where muscle power provides a primary means of transportation within a region. An equally ancient solution was implemented in many cultures — things in the water weighed far less and took less effort to move since friction became negligible. Close to the seacoast, rivers often provided adequate waterways, but the Appalachian Mountains, 400 miles (640 km) inland, running over 1,500 miles (2,400 km) long as a barrier range with just five places where mule trains or wagon roads could be routed,[3] presented a great challenge. Passengers and freight had to travel overland, a journey made more difficult by the rough condition of the roads. In 1800, it typically took 2.5 weeks to travel overland from New York to Cleveland, Ohio [460 miles (740 km)]; 4 weeks to Detroit [612 miles (985 km)].[4]

The principal exportable product of the Ohio Valley was grain, which was a high-volume, low-priced commodity, bolstered by supplies from the coast. Frequently it was not worth the cost of transporting it to far-away population centers. This was a factor leading to farmers in the west turning their grains into whiskey for easier transport and higher sales, and later the Whiskey Rebellion. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, it became clear to coastal residents that the city or state that succeeded in developing a cheap, reliable route to the West would enjoy economic success, and the port at the seaward end of such a route would see business increase greatly.[5] In time, projects were devised in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and relatively deep into the coastal states.

Proposals

- Early proposals

The successes of the Canal du Midi in France (1681), Bridgewater Canal in Britain (fully completed 1769), and Eiderkanal (superseded by today's Kiel Canal) in Denmark (later Germany) (1784) spurred on what was called in Britain "canal mania". The idea of a canal to tie the East Coast to the new western settlements was already in the air by 1724: New York provincial official Cadwallader Colden made a passing reference (in a report on fur trading) to improving the natural waterways of western New York.

Two men, Gouverneur Morris and Elkanah Watson, were early proponents of a canal along the Mohawk River. Their efforts led to the creation of the Western and Northern Inland Lock Navigation Companies in 1792 (which took the first steps to improve navigation on the Mohawk and construct a canal between the Mohawk and Lake Ontario),[6] but the company proved that private financing was insufficient.

- Potomac/Patowmack precedent

George Washington led a partly enduring effort to turn the Potomac River into a navigable link to the west, sinking substantial energy and capital into the Patowmack Canal from 1785 until his death fourteen years later.

By 1788 Washington's Potomac Company was successful in constructing five locks which took boats 4,500 feet (1,400 m) past the Potomac Great Falls. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal superseded the Potomac Canal in 1823.

Christopher Colles (who was familiar with the Bridgewater Canal) surveyed the Mohawk Valley, and made a presentation to the New York state legislature in 1784 proposing a canal from Lake Ontario. The proposal drew attention and some action but was never implemented.

- Scheme

Jesse Hawley finally got the canal built. He had envisioned encouraging the growing of large quantities of grain on the Western New York plains (then largely unsettled) for sale on the Eastern seaboard. However, he went bankrupt trying to ship grain to the coast. While in Canandaigua debtors' prison, Hawley began pressing for the construction of a canal along the 90-mile (140 km)-long Mohawk River valley with support from Joseph Ellicott (agent for the Holland Land Company in Batavia). Ellicott realized that a canal would add value to the land he was selling in the western part of the state. He later became the first canal commissioner.

Engineering requirements

The Mohawk River (a tributary of the Hudson) rises near Lake Ontario and runs in a glacial meltwater channel just north of the Catskill range of the Appalachian Mountains, separating them from the geologically distinct Adirondacks to the north. The Mohawk and Hudson valleys form the only cut across the Appalachians north of Alabama, allowing an almost complete water route from New York City in the south to Lakes Ontario and Erie in the west. Along its course and from these lakes, other Great Lakes, and to a lesser degree, related rivers, a large part of the continent's interior (and many settlements) would be made well connected to the Eastern seaboard.

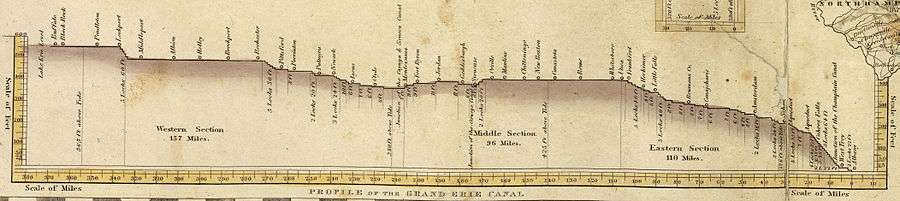

The problem was that the land rises about 600 feet (180 m) from the Hudson to Lake Erie. Locks at the time could handle up to 12 feet (3.7 m), so even with the heftiest cuttings and viaducts, fifty locks would be required along the 360-mile (580 km) canal. Such a canal would be expensive to build even with modern technology; in 1800, the expense was barely imaginable. President Thomas Jefferson called it "a little short of madness" and rejected it; however, Hawley interested New York Governor DeWitt Clinton in the project. There was much opposition, and the project was ridiculed as "Clinton's folly" and "Clinton's ditch." In 1817, though, Clinton received approval from the legislature for $7 million for construction.[7]

The original canal was 363 miles (584 km) long, from Albany on the Hudson to Buffalo on Lake Erie. The channel was cut 40 feet (12 m) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, with removed soil piled on the downhill side to form a walkway known as a towpath.[7]

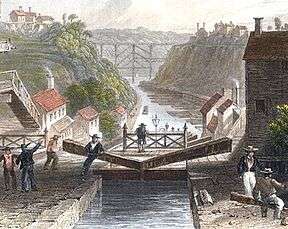

Its construction, through limestone and mountains, proved a daunting task. The canal was built using some of the most advanced engineering technology from Holland. In 1823 construction reached the Niagara Escarpment, necessitating the building of five locks along a 3-mile (4.8 km) corridor to carry the canal over the escarpment. To move earth, animals pulled a "slip scraper" (similar to a bulldozer). The sides of the canal were lined with stone set in clay, and the bottom was also lined with clay. The stonework required hundreds of German masons, who later built many of New York's buildings. All labor on the canal depended upon human (and animal) power or the force of water. Engineering techniques developed during its construction included the building of aqueducts to redirect water; one aqueduct was 950 feet (290 m) long to span 800 feet (240 m) of river. As the canal progressed, the crews and engineers working on the project developed expertise and became a skilled labor force.

Operation

Canal boats up to 3.5 feet (1.1 m) in draft were pulled by horses and mules on the towpath. This canal has one towpath generally on the north side. When canal boats met, the boat with the right of way remained on the towpath side of the canal. The other boat steered toward the berm (or heelpath) side of the canal. The driver (or "hoggee", pronounced HO-gee) of the privileged boat kept his towpath team by the canalside edge of the towpath, while the hoggee of the other boat moved to the outside of the towpath and stopped his team. His towline would be unravelled from the horses, go slack, fall into the water and sink to the bottom while his boat decelerated on with its remaining momentum. The privileged boat's team would step over the other boat's towline with their horses pulling the boat over the sunken towline without stopping. Once clear, the other boat's team would continue on its way.

Pulled by teams of horses canal boats still moved slowly but methodically shrinking time and distance. Efficiently, the nonstop smooth method of transportation cut nearly in half the travel time between Albany and Buffalo moving day and night. Venturing West men and women boarded packets to visit relatives or solely for a relaxing excursion. Emigrants took passage on freight boats camping on deck or on top of crates. Packet boats serving passengers exclusively reached speeds of up to five miles an hour and ran at much more frequent intervals than cramped, bumpy stages.[8]

Packet boats measuring up to seventy-eight feet in length and fourteen and a half feet across made ingenious use of space in order to accommodate up to forty passengers at night and up to three times as many in the daytime.[9] The best examples furnished with carpeted floors, stuffed chairs, and mahogany tables stocked with current newspapers and books served as sitting rooms during the days. At mealtimes crews transformed the cabin into dining rooms. Drawing a curtain across the width of the room divided the cabin into ladies' and gentlemen's sleeping quarters in the evening hours. Pull down tiered beds folded from the walls and additional cots could be hung from hooks in the ceiling. Some captains hired musicians and held dances.[9] The canal had brought civilization into the wilderness.

The Lehigh and Erie Canals

Two early 19th century canals had inordinately large impacts on the demographic and industrial development of the United States. The daring Erie Canal, begun in 1815 after a decade of debate and contemplation was a bid to join the port of New York City to the promise of the Great Lakes, just then undergoing rapid settlement as the 1779 Sullivan Expedition had brushed aside the Iroquois and opened the Northwest Territory to settlement.

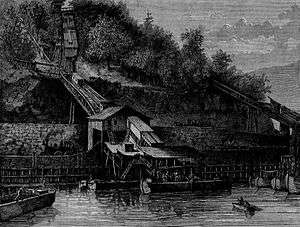

The Lehigh Canal

Perhaps in part inspired by the news of the Erie's technological achievements, the privately funded Lehigh Canal was an achievement brought about by the energy needs of two visionary industrialists, the politically connected Erskine Hazard and his older partner Josiah White, who together built the Lehigh Canal and the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, founding towns, mines, and building economically productive mining and transportation infrastructure from a wilderness in Eastern Pennsylvania south and west of the Poconos in the Anthracite creating folded ridges of the Ridge and Valley Appalachians. Not a true canal, the 'Lehigh navigation', was the type of canal built along the line of a river valley (within its drainage basin) and parallel to the fall of the watercourse. The Lehigh Canal for a time was two separate civil engineering projects constructed 20 years apart that stretched over two parts of the Lehigh River and totaling 72-mile (116 km) along the Lehigh River in eastern Pennsylvania.

Pictures

Loading coal at the Mauch Chunk chutes, 1873

Loading coal at the Mauch Chunk chutes, 1873 Weigh lock with scales to determine tolls, 1873

Weigh lock with scales to determine tolls, 1873- The canal passing through Bethlehem, 1907

Remains of Lock 25, 2006

Remains of Lock 25, 2006 Image of Gate entrance of Lock 28

Image of Gate entrance of Lock 28 Stacked rock detail of lock wall of Lock 28 near White Haven, 2008

Stacked rock detail of lock wall of Lock 28 near White Haven, 2008

See also

Notes

- ↑ Travel from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh in the 1820s would take 3-4 weeks by wagon road, 2-3 weeks walking diligently, and 10-14 days on horseback. When the Pennsylvania Canal System began operating, a heavy cargo of iron products could travel from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh in just four days, crossing over the Allegheny heights via the inclined planes and cable railroad technology of the Allegheny Portage Railroad.

References

- Bartholomew, Ann M.; Metz, Lance E.; Kneis, Michael (1989). DELAWARE and LEHIGH CANALS, 158 pages (First ed.). Oak Printing Company, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Center for Canal History and Technology, Hugh Moore Historical Park and Museum, Inc., Easton, Pennsylvania. ISBN 0930973097. LCCN 89-25150.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ James E. Held (July 1, 1998). "The Canal Age". Archaeology (online). A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America (July 1, 1998). Retrieved 2016-06-12.

On the settled eastern seaboard, forest decimation created an energy crisis for coastal cities, but the lack of water- and roadways made English coal shipped across the Atlantic cheaper in Philadelphia than Pennsylvania anthracite mined 100 miles away.... George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and other founding fathers believed they were the key to the New World's future.

- ↑ The five east-west crossings of the Appalachians are South to North:

• Plains of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi (around the bottom),

• the Cumberland Gap pass connecting North Carolina/Southern Virginia with Kentucky/Tennessee,

• the Cumberland Narrows pass connecting Cumberland Western Maryland/Northern Virginia with West Virginia and Western Pennsylvania via Brownsville, Pennsylvania and the Monongahela River or the Youghiogheny River valley (both of the Ohio & Mississippi river system),

• the gaps of the Allegheny connecting the Susquehanna River Valley in central Pennsylvania with the Allegheny River valley (and again the Ohio Country),

• and lastly, the Mohawk River water gap and valley tributary of the Hudson River, creating what later advertising would call the level water route westwards. - ↑ "Railroad Travel Rates, 1800–1930".

- ↑ Joel Achenbach, "America's River; From Washington and Jefferson to the Army Corps of Engineers, everyone had grandiose plans to tame the Potomac. Fortunately for us, they all failed". The Washington Post, May 5, 2002; p. W.12.

- ↑ Calhoun, Daniel Hovey. The American civil engineer: Origins and conflict. Technology Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1960.

- 1 2 Finch, Roy G. (1925). "The Story of the New York State Canals" (PDF). New York State Engineer and Surveyor (republished by New York State Canal Corporation). Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ↑ Sheriff, Carol (1996). The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress 1817-1862. Hill & Wang. p. 54.

- 1 2 Sheriff, Carol (1996). The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress 1817-1862. Hill & Wang. p. 59.

External links

- Canal & River Trust's Canal history

- The Canal Age, History of transport 1760-1840

- National Canal Museum: Lehigh Navigation

- Historic photos of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Canal

- Delaware & Lehigh Canal State Heritage Corridor

- Lehigh Canal History

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canals. |

Template:National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

Template:National Register of Historic Places in Louisiana

Template:National Register of Historic Places in Mississippi