Candra Naya

| Candra Naya | |

|---|---|

|

Candra Naya building below the super block Green Central City. | |

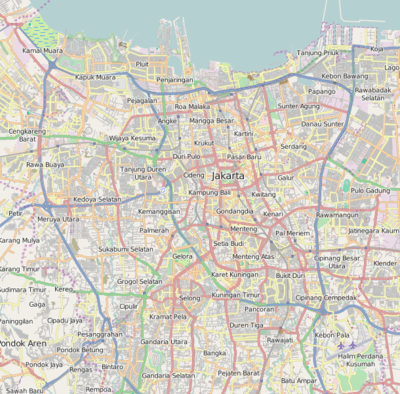

location within Jakarta | |

| General information | |

| Status | restored |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | Chinese |

| Location | Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Address | Jalan Gajah Mada |

| Coordinates | 6°8′50″S 106°48′55″E / 6.14722°S 106.81528°ECoordinates: 6°8′50″S 106°48′55″E / 6.14722°S 106.81528°E |

| Estimated completion | late 18th-century;[1] or 1807[2][3] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | anonymous |

Candra Naya (Hokkien: Sin Ming Hui) is an 18th-century historic building in Jakarta, Indonesia. It was home to the Khouw family of Tamboen, most notably its highest-ranking member: Khouw Kim An, the last Majoor der Chinezen ('Major of the Chinese') of Batavia (in office from 1910 until 1942).[4][5] Although among the grandest colonial residences in the capital and protected by heritage laws, the compound was almost completely demolished by its new owners, the conglomerate Modern Group.[6] The main halls have survived only thanks to vocal protests from heritage conservation groups.[6]

Building

Candra Naya was built in 1807[2] or earlier in the late 18th-century.[1] The most notable Chinese features of the house are its traditional curving roof, its Tou-Kung roof frame and its moon gates. The compound consisted originally of three main buildings, surrounded by ancillary buildings to its north and south. The three main buildings consist of a one-floored reception hall; a two-floored, semi-private central hall for worship; and the private, two-floored rear building for the family. The main buildings were separated from each other by a series of inner courtyards. The ancillary buildings to the north and south were one-floored structures, and were used as service quarters and accommodation for children, concubines and servants. In 1995, the two-floored central buildings were demolished to make way for a superblock. Due to protests from heritage groups, demolition work was halted. As of now, the only original building is the one-floored reception hall. The other main buildings were temporarily dismantled to allow for construction of the superblock, then reassembled and restored. The rear building was never rebuilt.[7]

History

Candra Naya was constructed in the early 19th-century on the grounds of what had been an 18th-century country house, landhuis Kroet.[3] The Chinese compound has the same style as buildings located at 168 and 204 Jalan Gajah Mada. All three houses were constructed for the family of the Batavian magnate and landlord Khouw Tian Sek, Luitenant der Chinezen (died in 1843). Following the independence of Indonesia, 168 was converted into SMA 2, a state school, while 204 became the Embassy of the People's Republic of China. With the exception of Candra Naya building, none of these has survived.[3]

The Khouw family of Tamboen

The history surrounding Candra Naya is not very well-recorded. The building was originally a private residence of the Khouw family of Tamboen. They trace their roots in Java to Khouw Tjoen, an 18th-century migrant from China who arrived first in Tegal, Central Java, then moved to Batavia. His son, Luitenant Khouw Tian Sek, became one of the colony's wealthiest magnates when his rural landholdings along Molenvliet canal became prime urban property thanks to Batavia's southwards expansion.[1][4]

One of Luitenant Khouw Tiang Sek's grandsons, Khouw Yauw Kie, served as Kapitein der Chinezen on Batavia's Chinese Council in the late 19th-century. Kapitein Khouw Yauw Kie probably lived at Candra Naya. The Kapitein's cousin, Khouw Kim An, later inherited the house, and went on to become the last Majoor der Chinezen of Batavia, the colony's highest Chinese civil authority, from 1910 until 1918, then again from 1927 until his death in 1945. Majoor Khouw Kim An lived at Molenvliet West 185, which later became Candra Naya.[1] Due to the building's association with its last resident, it is often referred to in popular parlance as Rumah Majoor (or the Majoor's House).

Candra Naya Social Union

During the Japanese occupation, governance by Chinese officers was suppressed. Majoor Khouw Kim An died in a concentration camp in 1945;[8] and his house was inherited by his family, who either sold or donated it to a Chinese social and educational organisation, called Sin Ming Hui, or Perkumpulan Sinar Baru in Bahasa (the "New Light Society").[8] Sin Ming Hui used the building for an educational institute that later became Tarumanegara University); a medical clinic that later became Sumber Waras Hospital); as well as a sports and photography group.[1][8] In 1965, under the recommendation of the Lembaga Pembina Kesatuan Bangsa ("The Board of Trustees of National Unity"), Sin Ming Hui was renamed to Perkoempoelan Sosial Tjandra Naja (Tjandra Naja Social Union). Tjandra Naja is now spelt Candra Naya.[8] It was a popular wedding venue during the 1960s and 1970s.[2] The building was made a cultural property by the city of Jakarta in 1972, by the Ministry of Education and Culture in 1988, and was clearly stipulated in the Law of the National Cultural Heritage in 1992.[3]

Dispute and demolition

In 1993, certain descendants of the Khouw family claimed ownership of the building. The dispute ended when the building was sold to Modern Group, a conglomerate owned by Samadikun Hartono. Hartono intended to demolish the compound and erect a new superblock of offices and apartments, called Green Central City.[2] Another plan was to moved the whole compound to Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. In 1995, three of the original buildings were demolished, prompting widespread protests which led to a compromise, whereby the main buildings of the old compound would be retained as the lobby of the new superblock.[2] Construction proceeded until the developer suffered severe financial losses during the economics crisis of mid-1997.

Restoration

On February 2012, the main buildings of Candra Naya were reassembled after being temporarily dismantled to make way for the construction of Green Central City. The ancillary buildings and the gazebo were also rebuilt after being completely demolished. The rear private building was never rebuilt.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Merrillees 2000, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diyah Wara 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Naniek Widayati 2003, p. 89.

- 1 2 Wright, Arnold (1909). wentieth Century Impressions of Netherlands India. Its History, People, Commerce, Industries and Resources. London: Lloyd's Greater Britain Pub. Co.

- ↑ Erkelens, Monique (2013). The decline of the Chinese Council of Batavia: the Loss of Prestige and Authority of the Traditional Elite amongst the Chinese Community from the End of the Nineteenth Century until 1942. (PDF). Leiden: Leiden University. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- 1 2 "The Jakarta Post". Candra Naya, besieged but still charming. August 2, 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Naniek Widayati 2003, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 Naniek Widayati 2003, p. 90.

Cited books

- Diyah Wara (November 6, 2012). "Candra Naya, "Mayor House" di Jakarta". Asosiasi Peranakan Tionghoa Indonesia (in Indonesian). Asosiasi Peranakan Tionghoa Indonesia. Archived from the original on 2016-11-12. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- Merrillees, Scott (2000). Batavia in Nineteenth Century Photographs. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789813018778.

- Naniek Widayati (2003). "Candra Naya Antara Kejayaan Masa Lalu dan Kenyataan Sekarang" [Candra Naya Between The Glory of the Past and The Present Reality]. Dimensi Journal of Architecture and Built Environment (in Indonesian). 31 (2). eISSN 2338-7858. ISSN 0126-219X. Archived from the original on 2016-11-12. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Candra Naya. |