Shale gas in the United States

Shale gas in the United States is rapidly increasing as an available source of natural gas. Led by new applications of hydraulic fracturing technology and horizontal drilling, development of new sources of shale gas has offset declines in production from conventional gas reservoirs, and has led to major increases in reserves of US natural gas. Largely due to shale gas discoveries, estimated reserves of natural gas in the United States in 2008 were 35% higher than in 2006.[1]

In 2007, shale gas fields included the #2 (Barnett/Newark East) and #13 (Antrim) sources of natural gas in the United States in terms of gas volumes produced.[2] The number of unconventional natural gas wells in the US rose from 18,485 in 2004 to 25,145 in 2007 and is expected to continue increasing[3] until about 2040.[4]

The economic success of shale gas in the United States since 2000 has led to rapid development of shale gas in Canada, and, more recently, has spurred interest in shale gas possibilities in Europe, Asia, and Australia. It has been postulated that there may be a 100-year supply of natural gas in the United States, but only 11 years of gas supply is in the form of proved reserves.[5]

Shale gas production

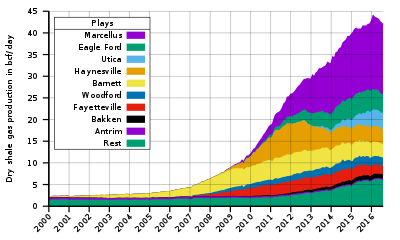

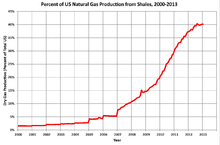

US shale gas production has grown rapidly in recent years after a long-term effort by the natural gas industry in partnership with the Department of Energy to improve drilling and extraction methods while increasing exploration efforts.[6][7] US shale production was 2.02 trillion cubic feet (57 billion cubic metres) in 2008, a jump of 71% over the previous year.[8] In 2009, US shale gas production grew 54% to 3.11 trillion cubic feet (88 billion cubic metres), while remaining proven US shale reserves at year-end 2009 increased 76% to 60.6 trillion cubic feet (1.72 trillion cubic metres).[9] In its Annual Energy Outlook for 2011, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) more than doubled its estimate of technically recoverable shale gas reserves in the US, to 827 trillion cubic feet (23.4 trillion cubic metres) from 353 trillion cubic feet (10.0 trillion cubic metres), by including data from drilling results in new shale fields, such as the Marcellus, Haynesville, and Eagle Ford shales. In 2012 the EIA lowered its estimates again to 482 tcf.[10] Shale production is projected to increase from 23% of total US gas production in 2010 to 49% by 2035.[11]

The availability of large shale gas reserves in the US has led some to propose natural gas-fired power plants as lower-carbon emission replacements for coal plants, and as backup power sources for wind energy.[13][14]

In June 2011, a New York Times article reported that "not everyone in the Energy Information Administration agrees" with the optimistic projections of reserves, and questioned the impartiality of some of the reports issued by the agency. Two of the primary contractors, Intek and Advanced Resources International, which provided information for the reports also have major clients in the oil and gas industry. "The president of Advanced Resources, Vello A. Kuuskraa, is also a stockholder and board member of Southwestern Energy, an energy company heavily involved in drilling for gas" in the Fayetteville Shale, according to the report in The New York Times. The article was criticized by, among others, the New York Times own Public editor for lack of balance, in omitting facts and viewpoints favorable to shale gas production and economics.[15] Other critics of the article included bloggers at Forbes and the Council on Foreign Relations.[16][17] Also in 2011, Diane Rehm had Urbina; Seamus McGraw, writer and author of "The End of Country"; Tony Ingraffea, a professor of engineering at Cornell; and John Hanger, former secretary of Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection; on a radio call-in show about Urbino's articles and the broader subject. The associations representing the natural gas industry, such as America's Natural Gas Alliance, were invited to be on the program but declined.[18]

In June 2011, when Urbino’s New York Times article appeared, the latest figures for US proved reserves of shale gas were 97.4 trillion cubic feet, as of the end of 2010.[19] Over the next three years 2011 through 2013, shale gas production totaled 28.3 trillion cubic feet, about 29% of the end-of-2010 proved reserves. But contrary to concerns of overstated reserves quoted in his article, both shale gas production and shale gas proved reserves have increased. US shale gas production in June 2011 was 21.6 billion cubic feet per day of dry gas. Since then, shale gas production has increased, and by March 2015 was 41.1 billion cubic feet per day, almost double the June 2011 rate, and provided 55% of total US dry natural gas production.[20] Despite the rapidly increasing production, companies replaced their proved reserves much faster than production, so that by the end of 2013, companies reported that shale gas proved reserves still in the ground had grown to 159.1 TCF, an increase of 63% over the end of 2010 reserves.[21]

Advances in technology or experience can lead to greater productivity. The US Energy Information Administration has reported that drilling for shale gas and light tight oil in the United States became much more efficient throughout the period 2007-2014. In terms of oil produced per day of rig drilling time, Bakken wells drilled in January 2014 produced 2.4 times as much oil as those drilled five years earlier, in January 2009. In the Marcellus Gas Trend, wells drilled in January 2014 produced more than nine times as much gas per day of drilling rig time as those drilled five years previously, in January 2009.[22][23]

History

Shale gas was first extracted as a resource in Fredonia, New York, in 1825,[24] in shallow, low-pressure fractures.

The Big Sandy gas field, in naturally fractured Devonian shales, started development in 1915, in Floyd County, Kentucky.[25] By 1976, the field sprawled over thousands of square miles of eastern Kentucky and into southern West Virginia, with five thousand wells in Kentucky alone, producing from the Ohio Shale and the Cleveland Shale, together known locally as the "Brown Shale." Since at least the 1940s, the shale wells had been stimulated by detonating explosives down the hole. In 1965 some operators started hydraulic fracturing the wells, using relatively small fracs: 50,000 pounds of sand and 42,000 gallons of water; the frac jobs generally increased production, especially from lower-yielding wells.[26] The field had an expected ultimate recovery of two trillion cubic feet of gas, but the average per-well recovery was small, and largely depended on the presence of natural fractures.[27]

Other commercial gas production from Devonian-age shales became widespread in the Appalachian, Michigan, and Illinois basins in the 1920s, but production was usually small.[28]

Federal support

Federal price controls on natural gas led to shortages in the 1970s.[28]

Faced with declining natural gas production, the federal government invested in many supply alternatives, including the Eastern Gas Shales Project, which lasted from 1976 to 1992, and the annual FERC-approved research budget of the Gas Research Institute, which was funded by a tax on natural gas shipments from 1976 to 2000.[29] The Department of Energy partnered with private gas companies to complete the first successful air-drilled multi-fracture horizontal well in shale in 1986. Microseismic imaging, an important input to both hydraulic fracturing in shale and offshore oil drilling, originated from coalbed research at Sandia National Laboratories.

The Eastern Gas Shales Project concentrated on extending and improving recoveries in known productive shale gas areas, particularly the greater Big Sandy Gas Field of Kentucky and West Virginia. The program applied two technologies that had been developed previously by industry, massive hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, to shale gas formations.[30] In 1976 two engineers for the federally funded Morgantown Energy Research Center (MERC) patented an early technique for directional drilling in shale.[31]

The federal government also provided tax credits and rules benefiting the industry in the 1980 Energy Act. Gas production from Devonian shales was exempted from federal price controls, and Section 29 tax credits were given for unconventional gas, including shale gas, from 1980 to 2000.[29]

Although the work of the Gas Research Institute and the Eastern Gas Shales Project had increased gas production in the southern Appalachian Basin and the Michigan Basin, in the late 1990s shale gas was still widely seen as marginal to uneconomic without tax credits, and shale gas provided only 1.6% of US gas production in 2000, when the federal tax credits expired.[28] The Eastern Gas Shales Project had tested a wide range of stimulation methods, but the DOE concluded that stimulation alone could not make the eastern gas shales economic.[32] The US Geological Survey in 1995 noted that future production of gas from the eastern shales would depend on future improvements in technology.[33] However, according to some analysts, the federal programs had planted the seeds of the coming shale gas boom.[34]

In 1991, Mitchell Energy completed the first horizontal frac in the Texas Barnett shale, a project subsidized by the Gas Research Institute, which was funded by a federal tax on gas pipelines. The first Barnett horizontal frac was an economic failure, however, as were Mitchell's later experiments with horizontal wells. The Barnett Shale boom became highly successful with vertical wells, and it was not until 2005 that horizontal wells being drilled in the Barnett outnumbered vertical wells.[28] Throughout the 1990s, Gas Resource Institute partnered with Mitchell Energy in applying a number of other technologies in the Barnett Shale. The then-vice president of Mitchell Energy recalled: "You cannot diminish DOE's involvement."[35]

Barnett and beyond

Mitchell Energy began producing gas from the Barnett Shale of North Texas in 1981, but the results at first were uneconomic. The company persevered for years in experimenting with new techniques. Mitchell soon abandoned the foam frac method that was developed by the Eastern Gas Shales Project, in favor of nitrogen gel-water fracs. Mitchell achieved the first highly economic fracture completion of the Barnett Shale in 1998, by using slick-water fracturing.[36][37] According to the US Geological Survey: "It was not until development of the Barnett Shale play in the 1990s that a technique suitable for fracturing shales was developed"[38] Although Mitchell experimented with horizontal wells, early results were not successful, and the Barnett Shale boom became highly successful with vertical wells. 2005 was the first year that the majority of new Barnett wells drilled were horizontal; by 2008, 94 percent of the Barnett wells drilled were horizontal.[28]

Since the success of the Barnett Shale, natural gas from shale has been the fastest growing contributor to total primary energy (TPE) in the United States, and has led many other countries to pursue shale deposits. According to the IEA, the economical extraction of shale gas more than doubles the projected production potential of natural gas, from 125 years to over 250 years.[39]

In 1996, shale gas wells in the United States produced 0.3 trillion cubic feet (8.5 billion cubic metres), 1.6% of US gas production; by 2006, production had more than tripled to 1.1 trillion cubic feet (31 billion cubic metres) per year, 5.9% of US gas production. By 2005 there were 14,990 shale gas wells in the US.[40] A record 4,185 shale gas wells were completed in the US in 2007.[41]

In 2005, energy exploration of the Barnett Shale in Texas, resulting from new technology, inspired an economic confidence in the industry as similar operations soon followed across the Southeast, including at Arkansas' Fayetteville Shale and Louisiana's Haynesville Shale.[42]

In January 2008, a joint study between Pennsylvania State University and State University of New York at Fredonia professors Terry Engelder, Geoscience professor at Penn State, and Gary G. Lash increased estimates as much as 250 times over the previous estimate for the Marcellus shale by the U.S. Geological Survey.[42] The report circulated throughout the industry.[43] In 2008, Engelder and Nash had noted a gas rush was occurring[43] and the New York Times' "There’s Gas in Those Hills" was an in-depth look at the development, noting investments by Texas-based Range Resources and increased leasing amongst Anadarko Petroleum, Chesapeake Energy and Cabot Oil & Gas.

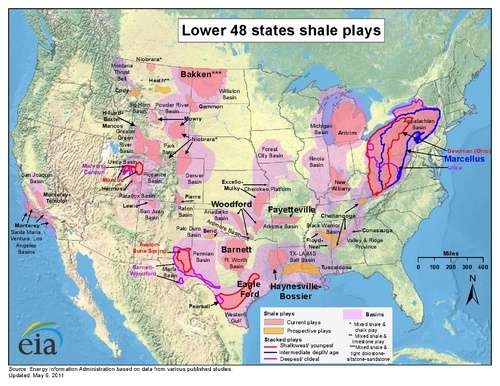

Shale gas by location

Antrim Shale, Michigan

The Antrim Shale of Upper Devonian age produces along a belt across the northern part of the Michigan Basin.[44] Although the Antrim Shale has produced gas since the 1940s, the play was not active until the late 1980s. Unlike other shale gas plays such as the Barnett Shale, the natural gas from the Antrim appears to be biogenic gas generated by the action of bacteria on the organic-rich rock.[45]

In 2007, the Antrim gas field produced 136 billion cubic feet (3.9 billion cubic metres) of gas, making it the 13th largest source of natural gas in the United States.[2]

Barnett Shale, Texas

The first Barnett Shale well was completed in 1981 in Wise County.[46] Drilling expanded greatly in the past several years due to higher natural gas prices and use of horizontal wells to increase production. In contrast to older shale gas plays, such as the Antrim Shale, the New Albany Shale, and the Ohio Shale, the Barnett Shale completions are much deeper (up to 8,000 feet). The thickness of the Barnett varies from 100 to 1,000 feet (300 m), but most economic wells are located where the shale is between 300 and 600 feet (180 m) thick. The success of the Barnett has spurred exploration of other deep shales.

In 2007, the Barnett shale (Newark East) gas field produced 1.11 trillion cubic feet (31 billion cubic metres) of gas, making it the second-largest source of natural gas in the United States.[2] The Barnett shale currently produces more than 6% of US natural gas production.[47]

In April 2015, Baker Hughes reports that there are 0 rig currently in activity at the Barnett gas field. (That doesn't mean 0 production as there are still plenty of wells already drilled but yet to be harvested).

Caney Shale, Oklahoma

The Caney Shale in the Arkoma Basin is the stratigraphic equivalent of the Barnett Shale in the Ft. Worth Basin. The formation has become a gas producer since the large success of the Barnett play.[48]

Conesauga Shale, Alabama

In 2008–2009, wells were drilled to produce gas from the Cambrian Conasauga shale in northern Alabama.[49] Activity is in St. Clair, Etowah, and Cullman counties.[50]

Fayetteville Shale, Arkansas

The Mississippian Fayetteville Shale produces gas in the Arkansas part of the Arkoma Basin. The productive section varies in thickness from 50 to 550 feet (170 m), and in depth from 1,500 to 6,500 feet (460 to 1,980 m). The shale gas was originally produced through vertical wells, but operators are increasingly going to horizontal wells in the Fayetteville. Producers include SEECO a subsidiary of Southwestern Energy Co. who discovered the play, Chesapeake Energy, Noble Energy Corp., XTO Energy Inc., Contango Oil & Gas Co., Edge Petroleum Corp., Triangle Petroleum Corp., and Kerogen Resources Inc.[51][52][53]

Floyd Shale, Alabama

The Floyd Shale of Mississippian age is a current gas exploration target in the Black Warrior Basin of northern Alabama and Mississippi.[54][55]

Gothic Shale, Colorado

In 1916, the United States Geographic Survey reported that Colorado alone had enough oil baring shale deposits to make 20,000 million barrels of crude oil; of which, 2,000 million barrels of gasoline then could be refined.[56] Bill Barrett Corporation has drilled and completed several gas wells in the Gothic Shale. The wells are in Montezuma County, Colorado, in the southeast part of the Paradox basin. A horizontal well in the Gothic flowed 5,700 MCF per day.[57]

Haynesville Shale, Louisiana

Although the Jurassic Haynesville Shale of northwest Louisiana has produced gas since 1905, it has been the focus of modern shale gas activity only since a gas discovery drilled by Cubic Energy in November 2007. The Cubic Energy discovery was followed by a March 2008 announcement by Chesapeake Energy that it had completed a Haynesville Shale gas well.[58] Haynesville shale wells have also been drilled in northeast Texas, where it is also known as the Bossier Shale.[59]

Collingwood-Utica Shale, Michigan

From 2008 through 2010 Encana accumulated a "large land position" (250,000 net acres) at an "average $150/acre" in the Collingwood Utica shale gas play in Michigan's Middle Ordovician Collingwood formation. Natural gas is produced from the Collingwood shale and the overlying Utica shale.[60]

The Michigan public land auction took place in early May 2010 in one of "America's most promising oil and gas plays".[61]

New Albany Shale, Illinois Basin

The Devonian-Mississippian New Albany Shale produces gas in the southeast Illinois Basin in Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky. The New Albany has been a gas producer in this area for more than 100 years, but recent higher gas prices and improved well completion technology have increased drilling activity. Wells are 250 to 2,000 feet (610 m) deep. The gas is described as having a mixed biogenic and thermogenic origin.

Pearsall Shale, Texas

Operators have completed approximately 50 wells in the Pearsall Shale in the Maverick Basin of south Texas. The most active company in the play has been TXCO Resources, although EnCana and Anadarko Petroleum have also acquired large land positions in the basin.[62] The gas wells had all been vertical until 2008, when TXCO drilled and completed a number of horizontal wells.[63]

Devonian shales, Appalachian Basin

Chattanooga and Ohio Shales

The upper Devonian shales of the Appalachian Basin, which are known by different names in different areas have produced gas since the early 20th century. The main producing area straddles the state lines of Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky, but extends through central Ohio and along Lake Erie into the panhandle of Pennsylvania. More than 20,000 wells produce gas from Devonian shales in the basin. The wells are commonly 3,000 to 5,000 feet (1,500 m) deep. The shale most commonly produced is the Chattanooga Shale, also called the Ohio Shale.[64] The US Geological Survey estimated a total resource of 12.2 trillion cubic feet (350 billion cubic metres) of natural gas in Devonian black shales from Kentucky to New York.[65]

Marcellus Shale

The Marcellus shale in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York, once thought to be played out, is now estimated to hold 168-516 trillion cubic feet (14.6 trillion cubic metres) still available with horizontal drilling.[66] It has been suggested that the Marcellus shale and other Devonian shales of the Appalachian Basin, could supply the northeast U.S. with natural gas.[67]

Utica Shale, New York and Ohio

In October 2009, the Canadian company Gastem, which has been drilling gas wells into the Ordivician Utica Shale in Quebec, drilled the first of its three state-permitted Utica Shale wells in New York. The first well drilled was in Otsego County.[68]

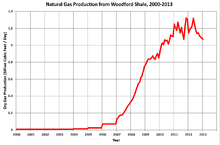

Woodford Shale, Oklahoma

The Devonian Woodford Shale in Oklahoma is from 50 to 300 feet (15 – 91 m) thick. Although the first gas production was recorded in 1939, by late 2004, there were only 24 Woodford Shale gas wells. By early 2008, there were more than 750 Woodford gas wells.[69] Like many shale gas plays, the Woodford started with vertical wells, then became dominantly a play of horizontal wells. The play is mostly in the Arkoma Basin of southeast Oklahoma, but some drilling has extended the play west into the Anadarko Basin and south into the Ardmore Basin.[70] The largest gas producer from the Woodford is Newfield Exploration; other operators include Devon Energy, Chesapeake Energy, Cimarex Energy, Antero Resources, St. Mary Land and Exploration, XTO Energy, Pablo Energy, Petroquest Energy, Continental Resources, and Range Resources. As of 2011, production from the Woodford Shale had peaked and was declining.[71][72][73]

Economic impacts

In the United States, development of shale resources supported 600,000 jobs in 2010.[74][75] Affordable domestic natural gas is essential to rejuvenating the chemical, manufacturing, and steel industries.[76] There are concerns that these changes may be reversed if exports of natural gas increase.[77] The American Chemistry Council determined that a 25% increase in the supply of ethane (a liquid derived from shale gas) could add over 400,000 jobs across the economy, provide over $4.4 billion annually in federal, state, and local tax revenue, and spur $16.2 billion in capital investment by the chemical industry.[78] They also note that the relatively low price of ethane would give United States manufacturers an essential advantage over many global competitors. Similarly, the National Association of Manufacturers estimated that high recovery of shale gas and lower natural gas prices will help U.S. manufacturers employ 1,000,000 workers by 2025 while lower feedstock and energy costs could help them reduce natural gas expenditures by as much as 11.6 billion by 2025.[79] America's Natural Gas Association (ANGA) estimates that lower gas prices will add an additional $926 of disposable household income annually between 2012 and 2015, and that the amount could increase to $2,000 by 2035.[80] Over a 100 billion dollars is going to be invested in the US Petrochemical industry and most of it in Texas.[81] Due to emergence of shale gas, coal consumption declined from 2009.[82]

One study finds that hyraulic fracturing has contributed to job growth and higher wages. The results of the study "suggest new oil and gas extraction led to an increase in aggregate US employment of 725,000 and a 0.5 percent decrease in the unemployment rate during the Great Recession".[83] Research shows that shale gas wells can have a significant adverse impact on some house prices, with groundwater-reliant homes declining 13% in value whereas piped-water homes will see an increase of 2-3%. The price increase of the latter is most likely due to the royalty payments that property owners get from gas extracted under their land.[84]

The issue of whether to export natural gas has split the business community. Manufacturers such as Dow Chemical are battling energy companies such as Exxon Mobil over whether the export of natural gas should be allowed. Manufacturers want to keep gas prices low, while energy companies have been working to raise the price of natural gas by convincing the government to allow them to export natural gas to more countries.[76] Manufacturers are concerned that increasing exports will hurt manufacturing by causing U.S. energy prices to rise.[77] Several recent studies suggest that the shale gas boom has given the U.S. energy intensive manufacturing sector a competitive advantage, causing a boom in energy intensive manufacturing sector exports, suggesting that the average dollar unit of U.S. manufacturing sector exports has almost tripled its energy content between 1996 and 2012.[85][86]

As of 2014, many energy companies have been cash flow negative, e.g. Antero and Chesapeake Energy, which pioneered the "land-grab approach"; Royal Dutch Shell has said "drilling for natural gas is a losing proposition". Southwestern Energy Co., the 5th largest US gas producer, which exploits the Fayetteville shale in Arkansas predicts to be cash flow positive in "years ahead". In 2013 the 20 largest exploration companies outspent their income by $11.5 billion, and by $29.9 billion in 2012.[87] The few companies which are spending less than they make are smaller and focus on quality land instead of quantity, such as Diamondback Energy Inc and RSP Permian Inc in West Texas, Andarko Petroleum Corp and ConocoPhilips[88]

Political impact

One study finds that shale booms increase support for conservatives and conservative interests. "Support for conservative interests rises and Republican political candidates gain votes after booms, leading to a near doubling in the probability of a change in incumbency. All of this change occurs at the expense of Democrats."[89]

Environmental issues

Complaints of uranium exposure and lack of water infrastructure emerged as environmental concerns for the rush.[90][91] In Pennsylvania, controversy has surrounded the practice of releasing wastewater from "fracking" into rivers which serve as consumption reserves.[92]

Methane release contributing to global warming is a concern.[93]

Popular culture

The rush has popularized the word “fracking” in American culture, which is slang for hydraulic fracturing.[94]

The Great Shale Gas Rush[95] refers to the growth in unconventional shale gas extraction in the early 21st-century.

Pennsylvania was featured in the Academy Award-nominated,[96] environmental documentary Gasland by Josh Fox in 2010.[97] Most of the filming for the 2012 Gus Van Sant dramatic film, Promised Land, starring Matt Damon, took place in the Pittsburgh area, although the setting is upstate New York.

See also

References

- ↑ Jad Mouawad, "Estimate places natural gas reserves 35% higher,", New York Times, 17 June 2009, accessed 25 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 US Energy Information Administration, Top 100 oil and gas fields, PDF file, retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ↑ Vidas H, Hugman B. ICF International. Availability, Economics, and Production Potential of North American Unconventional Natural Gas SuppliesPrepared for The INGAA Foundation, Inc. by: ICF International; 2008.

- ↑ "AEO2014 EARLY RELEASE OVERVIEW" EIA, December 2013. Accessed: December 2013.

- ↑ Nelder, Chris (2011-12-29). "What the Frack?". Slate. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ Simon Mauger; Dana Bozbiciu (1991 ɒɒɒɒɒ). "How Changing Gas Supply Cost Leads to Surging Production" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-10. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Associated Press (23 September 2012). "Fracking Developed With Decades of Government Investment". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- ↑ US Energy information Administration, Shale gas production, accessed 4 December 2009.

- ↑ US Energy information Administration, "Summary: US Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Natural Gas Liquids Proved Reserves 2009", http://www.eia.gov/pub/oil_gas/natural_gas/data_publications/crude_oil_natural_gas_reserves/current/pdf/arrsummary.pdf, accessed 5 January 2011.

- ↑ "AEO2012 Early Release Overview" (PDF).

- ↑ "Annual Energy Outlook 2012 Early Release Overview" (PDF). Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Statement on U.S.-China shale gas resource initiative, 17 November 2009.

- ↑ Peter Behr and Christa Marshall, "Is shale gas the climate bill's new bargaining chip?," New York Times, 5 August 2009.

- ↑ Tom Gjelten, "Rediscovering natural gas by hitting rock bottom," National Public Radio, 22 September 2009.

- ↑ Arthur S. Brisbane, “Clashing views on the future of natural gas,” New York Times, 16 July 2001.

- ↑ Helman, Christopher, "New York Times Is All Hot Air On Shale Gas", Forbes, June 27, 2011 1:37 pm. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ Levi, Michael, "Is Shale Gas a Ponzi Scheme?", Council on Foreign Relations website, June 27, 2011. The earlier Urbina article was “‘Enron Moment’: Insiders Sound Alarm amid a Natural Gas Rush”. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ "Natural Gas: Promise and Perils", Diane Rehm Show, NPR via WAMU, June 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ↑ US EIA, US Crude Oil and Natural Gas Proved Reserves, Data Table 4, 1 Aug. 2014.

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration, Shale in the United States 14 May 2015

- ↑ US EIA, US Crude Oil and Natural Gas Proved Reserves, Data Table 4, 14 Dec 2014.

- ↑ US EIA, Drilling efficiency is a key driver of oil and natural gas production, Today in Energy, 4 Nov. 3013.

- ↑ US EIA, Drilling productivity report, Excel spreadsheet linked to web page, 8 December 2014.

- ↑ "Name the gas industry birthplace: Fredonia, N.Y.?"

- ↑ Oil and gas history of Kentucky, 1900 to present Kentucky Geological Survey.

- ↑ E. O. Ray, Shale development in eastern Kentucky, US Energy Research and Development Administration, 1976.

- ↑ Jane Negus-de Wys, Anatomy of a large Devonian black shale gas field US Dept. of Energy

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zhongmin Wang and Alan Krupnick, A Retrospective Review of Shale Gas Development in the United States, Resources for the Futures, Apr. 2013.

- 1 2 Stevens, Paul (August 2012). "The 'Shale Gas Revolution': Developments and Changes". Chatham House. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ KEN MILAM, EXPLORER Correspondent. "Proceedings from the 2nd Annual Methane Recovery from Coalbeds Symposium". Aapg.org. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ↑ "National Energy Technology Laboratory: A Century of Innovation," NETL, 2010.

- ↑ Soeder and Kapelle, Water resources and the Marcellus Shale, US Geological Survey, 2009, May 2009.

- ↑ R.T. Ryder, "Appalachian Basin Province," in National Oil and Gas Assessment, 1995, US Geological Survey, p.60.

- ↑ Alex Trembath,US government and shale gas fracking, Breakthrough Institute, 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Michael Shellenberger, Interview with Dan Steward, Breakthrough Institute, 12 Dec. 2011.

- ↑ Miller, Rich; Loder, Asjylyn; Polson, Jim (6 February 2012). "Americans Gaining Energy Independence". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ The Breakthrough Institute. Interview with Dan Steward, former Mitchell Energy Vice President. December 2011.

- ↑ Laura R. H. Biewick, US Geological Survey, 2013.

- ↑ International Energy Agency (IEA). "World Energy Outlook 2011: Are We Entering a Golden Age of Gas?"

- ↑ Vello A. Kuuskraa, Reserves, production grew greatly during last decade Oil & Gas Journal, 3 Sept. 2007, p.35-39

- ↑ Louise S. Durham, "Prices, technology make shales hot," AAPG Explorer, July 2008, p.10.

- 1 2 "The Rush Is On", Steve Reilly. Pennsylvania Business Central. March 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

- 1 2 "Marcellus Shale Play’s Vast Resource Potential Creating Stir In Appalachia", American Oil and Gas Reporter. May 2008. Accessed December 18, 2010

- ↑ Michigan DEQ map: Antrim, PDF file, downloaded 12 February 2009.

- ↑

- ↑ Scott R. Reevbasins invigorate U.S. gas shales play, urnal, 22 Jan. 1996, p.53-58.

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration: Is U.S. natural gas production increasing?, Accessed 20 March 2009.

- ↑ Bill Grieser: Caney Shale, Oklahoma's shale challenge, PDF file, retrieved 25 February 2009

- ↑ Alabama State Oil and Gas Board (Nov. 2007):An overview of the Conesauga shale gas play in Alabama, PDF file, downloaded 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "Operators chase gas in three Alabama shale formations," Oil & Gas Jour., 21 Jan. 2008, p.49-50.

- ↑ Nina M. Rach, Triangle Petroleum, Kerogen Resources drilling Arkansas' Fayetteville shale gas, Oil & Gas Journal, 17 Sept. 2007, p.59-62.

- ↑ Fayetteville shale

- ↑ Fayetteville shale: reducing environmental impacts

- ↑ Mark J. Pawlewicz and Joseph R. hatch, Petroleum Assessment of the Chattanooga Shale/Floyd Shale Total Petroleum System, Black Warrior Basin, Alabama and Mississippi, US Geological Survey, Digital Data Series DDS-69-1, 2007, PDF file.

- ↑ Alabama Geological Survey, An overview of the Floyd Shale/Chattanooga Shale gas play in Alabama, July 2009, PDF file.

- ↑ 1916 Shale Discovery in Colorado

- ↑ "Barrett may haveParadox Basin discovery," Rocky Mountain Oil Journal, 14 Nov. 2008, p.1.

- ↑ Louise S. Durham, "Louisiana play a 'company maker'," AAPG Explorer, July 2008, p.18-36.

- ↑ Geology.Com: Haynesville Shale: news, map, videos, lease and royalty information

- ↑ Alan Petzet, ed. (May 7, 2010). "Explorations: Michigan Collingwood-Utica gas play emerging". Oil and Gas Journal. Houston, Texas.

- ↑ Brian Grow; Joshua Schneyer; Janet Roberts (June 25, 2012). "Special Report: Chesapeake and rival plotted to suppress land prices". Gaylord, Michigan: Reuters.

- ↑ Alan Petzet (2007-08-13). "More operators eye Maverick shale gas, tar sand potential". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. 107: 38–40. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "Maverick fracs unlock gas in Pearsall Shale". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. 107: 32–34. 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Richard E. Peterson (1982) A Geologic Study of the Appalachian Basin, Gas Research Institute, p.40, 45.

- ↑

- ↑ Unconventional natural gas reservoir in Pennsylvania poised to dramatically increase US Production 2008-01-17

- ↑ Arthur J. Pyron (2008-04-21). "Appalachian basin's Devonian: more than a "new Barnett shale"". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. 106 (15): 38–40. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Tom Grace, "Officials positive following gas-well tour," Oneonta Daily Star, 7 October 2009.

- ↑ Travis Vulgamore and others, "Hydraulic fracturing diagnostics help optimize stimulations of Woodford Shale horizontals," American Oil and Gas Reporter, Mar. 2008, p.66-79.

- ↑ David Brown, "Big potential boosts Woodford," AAPG Explorer, July 2008, p.12-16.

- ↑ Woodford Shale production, 2005–2011, The Oil Drum

- ↑ Oklahoma Geological Survey: Map of Woodford shale wells, accessed 25 February 2009

- ↑ Brian J. Cardott: Overview of Woodford gas-shale play in Oklahoma, 2008 update, PDF file, retrieved 25 February 2009

- ↑ IHS Global Insight, The Economic and Employment Contributions of Shale Gas in the United States, December 2011.

- ↑ Fetzer, Thiemo (24 April 2014). "Fracking Growth". Centre for Economic Performance Working Paper, London. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- 1 2 Feng, Zhaokui (24 January 2013). "The Impact of the Changing Global Energy Map on Geopolitics of the World". China-United States Exchange Foundation. Retrieved 2013-05-15.

- 1 2 Obel, Mike (1 March 2013). "Potential Surge Of US LNG Exports From Shale Natural Gas Boom Splits Corporate America; One Side Gets Allied With Environmentalists.". International Business Times. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

...the boom in production has created a rare fissure that runs through the heart of corporate America, pitting manufacturers such as Dow Chemical against energy giants such as the Exxon Mobil Corp. (NYSE:XOM), which have been seeking to raise the price of natural gas by pushing the government to allow them to export to more countries. That concerns manufacturers, which warn that such an export-heavy policy will result in higher energy prices in the U.S. and hurt manufacturing.

- ↑ American Chemistry Council, Shale Gas and New Petrochemicals Investment: Benefits for the Economy, Jobs, and U.S. Manufacturing, March 2011.

- ↑ PriceWaterhouseCoopers, A Renaissance in Shale Gas? December 2011.

- ↑ IHS Global Insight, The Economic and Employment Contributions of Natural Gas in the United States, December 2011.

- ↑ - Global Impact of American Shale by Laique Rehman CEO US Petrochemical

- ↑ Liam Denning. "Trump can’t make both coal and fracking great again" 2016-05-29. Quote: "The trend of gas taking market share from coal began in earnest in 2009 — which just happens to be when the cost of gas to produce electricity collapsed"

- ↑ Feyrer, James; Mansur, Erin; Sacerdote, Bruce. "Geographic Dispersion of Economic Shocks: Evidence from the Fracking Revolution" (PDF). doi:10.3386/w21624.

- ↑ Muehlenbachs, Lucija; Spiller, Elisheba; Timmins, Christopher. "The Housing Market Impacts of Shale Gas Development †". American Economic Review. 105 (12): 3633–3659. doi:10.1257/aer.20140079.

- ↑ Arezki, Rabah; Fetzer, Thiemo. "On the Comparative Advantage of U.S. Manufacturing: Evidence from the Shale Gas Revolution" (PDF). Journal of International Economics.

- ↑ "The Trade Implications of the U.S. Shale Gas Boom" (PDF).

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Gold, Russell (20 April 2014). "Energy Companies That Spend More Than They Make No Longer in Vogue". Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Gold, Russell (20 April 2014). "Smaller Drillers With Tight Focus On Quality of Sites Appeal to Investors". WSJ. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Fedaseyeu, Viktar; Gilje, Erik; Strahan, Philip E. (2015-12-01). "Voter Preferences and Political Change: Evidence from Shale Booms".

- ↑ “Fracking' mobilizes uranium in marcellus shale”, E Science News. October 25, 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

- ↑ “A developing issue: Water management, infrastructure needed for Marcellus gas production”, Farm and Dairy. November 9, 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

- ↑ "Pennsylvania Official: End Nears For Fracking Wastewater Releases", David Caruso. Huffington Post. 24 April 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011

- ↑ So What's the Matter With Shale Gas, Anyway? Environmental Groups Want It to Replace Coal, but Not at the Expense of Wind and Solar July 19, 2013 Wall Street Journal

- ↑ “Fracking for natural gas: EPA hearings bring protests”, Mark Clayton. Christian Science Monitor. September 13, 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

- ↑ Special Report: The Great Shale Gas Rush", National Geographic. October 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

- ↑ "'Gasland' Oscar nomination roils drilling industry", Andrew Maykuth. Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011

- ↑ “The Costs of Natural Gas, Including Flaming Water”, Mike Hale. New York Times. June 20, 2010. Accessed December 18, 2010

External links

- The Shale Gas Boom: The global implications of the rise of unconventional fossil energy, FIIA Briefing Paper 122, 2013, The Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

- A creative exploration of natural gas drilling and development in the Marcellus Shale

- Jackson School of Geosciences (Jan. 2007): Barnett Boom Ignites Hunt for Unconventional Gas Resources

- AAPG Explorer (Mar. 2001): Shale Gas Exciting Again

- Oil and Gas Investor (Jan. 2006): Shale Gas

- Marcellus Shale: horizontal drilling and hydrofracing

- The Haynesville Shale of Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas

- West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey: Geology of the Marcellus Shale PDF file, retrieved 2 January 2009.

- West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey: Enhancement of the Appalachian Basin Devonian shale resource base in the GRI hydrocarbon model PDF file, retrieved 2 January 2009.

- China Goes Shopping for Shale in U.S., Canada May 11, 2012