Capture of Wurst Farm

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Capture of Wurst Farm was an attack by the British 58th (2/1st London) Division (58th Division) against the German 36th Division on 20 September 1917, near Ypres, Belgium, during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, part of the Third Battle of Ypres (Battle of Passchendaele). Wurst Farm was at the lower end of Gravenstafel Ridge and several British attacks in the area since 31 July had been repulsed by the Germans. The British began a desultory bombardment on 31 August and the shelling became intense from 13 September, to "soften" the German defences, except in the area of the Fifth Army (General Hubert Gough), where the slow bombardment continued until the last 24 hours, before a hurricane bombardment was fired, to gain surprise.

XVIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse) of the Fifth Army was to advance onto the Gravenstafel Spur, an area held by the 36th Division since 8 September. The 58th Division (Major-General Hew Dalrymple Fanshawe) was to conduct the attack, between the 55th (West Lancashire) Infantry Division on the right flank and the 51st (Highland) Division on the left. The 58th Division objective was 1,000 yards (910 m) ahead, among German strongpoints on Wurst Farm Ridge, at the west end of Gravenstafel Spur.

The right-hand brigade made a decoy attack, while the left-hand brigade attacked from the left flank, concealed by mist. The feint captured Winnipeg cross-roads, as the main attack by three battalions one behind the other, advanced from Vancouver Farm, Keerselaere and took Hubner Farm. The two following battalions leap-frogged the leading battalion and turned right, half-way up the spur to reach Wurst Farm, keeping well up to the creeping barrage. The British took 301 prisoners and fifty machine-guns, then established outposts to the left, overlooking the Stroombeek valley.

Late in the afternoon a German counter-attack by the 234th Division to recover the Wilhelm (third) Line on the XVIII Corps front, was routed, with up to 50 percent casualties in some battalions. The 58th Division ascribed their success to excellent training, a good creeping barrage and smoke shell, which had thickened the mist and blinded the German defenders; gas shell barrages on the German reinforcement routes had depressed German morale. On 26 September, the 58th Division managed to advance further up the ridge.

Background

Wilhelm Stellung

The German 4th Army (General Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin) operation order for the defensive battle had been issued on 27 June.[1] From mid-1917, the area east of Ypres was defended by six German defensive positions: the front line, Albrecht Stellung (second line), Wilhelm Stellung (third line), Flandern I Stellung (fourth line), Flandern II Stellung (fifth line) and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). In between the German defence positions lay the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendaele.[2] The German defences had been arranged as a "forward zone", "main battle zone" and "rearward battle zone".[3] The front position, forward zone and much of the Albrecht Stellung at the front of the main zone had fallen since the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July – 2 August). The Wilhelm Stellung, 2,000 yards (1,800 m) behind the Albrecht Stellung, marked the rear of the main zone, which contained most of the field artillery supporting the front divisions but had become the front zone due to the earlier British advances. The rearward zone, between the Wilhelm Stellung and the Flandern I Stellung, contained the support and reserve assembly areas for Eingreif divisions, which had been specially trained to counter-attack British and French attacks, to recapture lost ground.[4]

The German defence scheme was based on a rigid defence of the front system and forward zone supported by counter-attacks from the Eingreif divisions. Local withdrawals according to the concept of elastic defence, had been rejected by Lossberg, the 4th Army Chief of Staff, who believed that they would disorganise the troops moving forward to counter-attack. Front line troops were not expected to cling to shelters, which were man traps but evacuate them as soon as the battle began, move forward and to the flanks to avoid British fire and then counter-attack. A small number of machine-gun nests and permanent garrisons were kept separate from the counter-attack organisation, to provide a framework for defence in depth, once an attack had been repulsed. German infantry equipment had been improved by the issue of thirty-six MG08/15 machine-guns per regiment, which gave German units more capacity for fire and manoeuvre.[5]

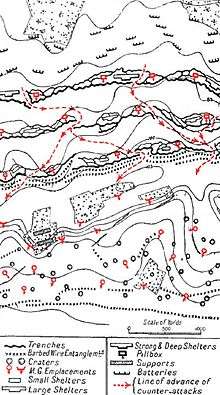

In September 1917, the Wilhelm Stellung section along Wurst Farm Ridge, the lower western slope of Gravenstafel Ridge, was still in German hands, despite the attacks in July and August. At the top of the spur looking down on the valley of the Lekkerboterbeek, were Vancouver Farm and the Triangle Farm redoubt between it and St. Julien. Farther back towards Gravenstafel was the Von Tirpitz redoubt and north-east of Winnipeg was the Wurst Farm fortification; north of the farm the ground dipped towards the Stroombeek.[6] From 8 September, the Wilhelm Stellung on this part of the front had been held by the 36th Division of the 4th Army, with Infantry regiments 175 and 128 and Grenadier Regiment 5, occupying frontages of 800–900 yards (730–820 m) opposite XVIII Corps, with one battalion each in the outpost zone, one in support and one in reserve behind Flandern I Stellung.[7]

British preparations

The British intended to overcome the German defence by making a shallower penetration, then fighting the principal battle against the German Eingreif divisions. New infantry formations were devised, to counter the German irregular pillbox zones and the impossibility of maintaining lines and waves of infantry on ground full of flooded shell-craters. Waves were replaced by a thin line of skirmishers leading small columns. The rifle, rather than hand-grenades, was made the primary infantry weapon and Stokes mortars were added to creeping barrages. "Draw net" barrages, where field guns began a barrage 1,500 yards (1,400 m) behind the German front line then crept towards it, were fired several times before the attack began.[8] More infantry was provided for the later stages of the advance, to defeat German counter-attacks by advancing no more than 1,500 yards (1,400 m), before digging-in. When the Germans counter-attacked, they would find the British organised in depth, protected by artillery and aircraft, rather than the small and disorganised groups of British infantry encountered in earlier battles and suffer many casualties to little effect.[9]

Prelude

Raids

The Fifth Army made several minor attacks in September, most of which failed and the attacks were stopped, except for smaller local operations by divisions.[10] On 1 September, the 58th Division took Spot Farm and two battalions conducted raids on 8 September. A pillbox close to the British front line, which blocked the route to Wurst Farm was damaged and a bunker in a fortified shell-hole was attacked and found to be connected to other shell-holes and a pillbox before the raiders retired. On 14 September, a battalion attacked Winnipeg and in the evening a German counter-attack took ground towards Springfield.[11]

Plan of attack

The ground around the Langemarck–Zonnebeke road was unfavourable for an attack, despite the drier weather of September, being low-lying, swampy and broken up on the approach by shelling in the weeks preceding, which slowed movement.[12] The attack on the Wurst Farm strongpoints, was part of the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, which on the 58th Division front, was intended to capture the Wilhelm Line and vicinity, at the west end of Gravenstafel Ridge, by an advance of about 1,000 yards (910 m). Attacks in July and August had failed and given the poor state of the ground, it was decided to make a Chinese attack. (A Chinese attack was a demonstration, intended to distract the defenders with genuine artillery bombardments, suggesting the beginning of an attack. Sometimes dummy soldiers were displayed to simulate an infantry advance. If successful, the Chinese attack would induce the Germans to return fire and reveal the position of hidden machine-guns and pillboxes.)[13] A frontal attack by the 173rd Brigade would be simulated on the right flank, while an outflanking move was made by the 174th Brigade from the left of the divisional front, attacking south-eastwards up the spur.[14]

Battle

20 September

Before the main attack, the 58th Trench Mortar Battery fired twenty shots at a pillbox and had ten hits, which demoralised the occupants. On the right flank, C Company of the 2nd/4th Battalion London Regiment, 173rd Brigade performed the Chinese attack to divert German attention and captured Winnipeg crossroads in the process. On the left flank, the 174th Brigade attacked with three battalions following each other on a battalion front. Triangle Farm was reached first and the garrison killed or captured, then Vancouver Farm was taken with its neighbouring pill-boxes were reduced.[15] The strongpoints beyond Vancouver Farm and Keerselaere were captured quickly and Hubner Farm on the edge of the spur, fell after being surrounded; seventy prisoners were taken by the 2/8th Post Office Rifles. The 2/5th London Rifle Brigade and the 2/6th Rifle Brigade in support and reserve, leap-frogged through the Post Office Rifles and turned half-right up the spur. Having reached the summit of the spur the two battalions advanced on Von Tirpitz redoubt and Wurst Farm from behind, keeping close behind the creeping barrage.[16]

The German defenders fought with determination but the redoubts were surrounded and stormed. Platoons and sections had all been given geographical objectives, such as pillboxes and emplacements and as these were outflanked and captured, 301 Germans were taken prisoner. Small parties then moved across the Stroombeek valley north to the left flank of the division and swept the valley with machine-gun fire from outposts, protecting the right flank of the 51st Highland Division around Quebec and Delta Farms; the 173rd Brigade then advanced to the summit of the ridge.[15][14] Two tanks supported the attack by the 58th Division, E.17 (Exterminator) and E.3 (Eclipse) of E battalion of the 1st Tank Brigade. The 55th Division on the right flank and a party of the 58th Division attacked the Germans at the Schuler Galleries on the divisional boundary but the tanks bogged and the infantry were pinned down by machine-gun fire; the galleries were eventually captured by the 55th Division, later in the day.[17]

At about 5:30 p.m. a large force of German infantry from the 234th Division advanced down the main ridge 1-mile (1.6 km) beyond the line now occupied by the 55th, 58th and 51st divisions. Just before 6:00 p.m., the 58th Division commenced firing with machine-guns and Lewis guns at 1,500 yards (1,400 m), which inflicted casualties and forced the numerous small German columns to deploy into line. When the estimated 2,000 German infantry were at 650 yards (590 m), British rifle-fire began and when the survivors were 150 yards (140 m) from the foremost divisional strongpoint, a British artillery barrage fell on them with an effect "beyond description and the enemy stampeded". After dark German patrols trickled forward and occupied an outpost position.[18]

Subsequent operations

26 September

During the attack by the Second Army and by V Corps of the Fifth Army, an attempt was made to advance another 800 yards (730 m) from Wurst Farm up Gravenstafel Spur towards Aviatik Farm, by the 175th Brigade on the right flank of the 58th Division. The right of the brigade moved up the north side of the Hanebeek valley, keeping touch with the 59th (2nd North Midland) Division (59th Division) on the right flank. The attack began at 5:50 a.m. in thick mist. Some troops lost direction and were then held up by fire from Dom Trench and a pillbox, after these were captured the advance resumed until stopped at Dear House, Aviatik Farm and Vale House, about 400 yards (370 m) short of the final objective. A counter-attack by Reserve Infantry Regiment 100 of the 23rd Reserve Division, pushed the British back from Aviatik Farm and Dale House and an attempt to regain them failed. Another attack at 6:11 p.m. reached Nile, on the divisional boundary with the 3rd Division. German troops trickling forward to Riverside and Otto pillboxes were stopped by artillery and machine-gun fire.[19] The 175th Brigade had 499 casualties.[20]

Victoria Cross

In the British Official History (1948), J. E. Edmonds recorded that Sergeant Alfred Knight of the 2/8th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Post Office Rifles), had rushed twelve Germans in a shell hole, killed three and captured a machine-gun. Soon after, he rushed another machine-gun nest, killed the gunner and captured the gun.[21][22]

I hardly know myself how it happened. The miracle of it all is that one comes through as I did without a scratch. Bullets rattled on my steel helmet – there were several significant dents and one hole – part of a book was shot away in my pocket; a photograph case and cigarette case probably saved my life from one bullet which must have passed under my armpit. I found a wounded Boche in a pillbox and offered to take him to a dressing station. In gratitude the German gave me a drink of brandy. This lad was one of the best.[23]

Looking back afterwards, it was all of a bit of a blur, but I can remember being fascinated by the pattern made all the way around me in mud by German bullets. I hardly knew how it happened! All I know is that I was up to my waist in mud at one time. I couldn't tell whether I had a watch or not; but I found a rig-out afterwards, so that was all right!— Alfred Knight[24]

Casualties

The 58th Division had 1,236 casualties from 20–25 September and took 301 prisoners from the 36th Division; other German casualties are unknown. The casualties of the 234th Division during its counter-attack, are also unknown but the divisional history referred to some battalions losing up to 50 percent of their strength.[25] On 26 September, the 175th Brigade had 499 casualties.[20]

Footnotes

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 143.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 284.

- ↑ Lupfer 1981, p. 14.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 292.

- ↑ Times 1918, p. 49.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 270.

- ↑ Simpson 2005, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 247.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 244.

- ↑ McCarthy 1995, pp. 66–69.

- ↑ Gibbs 1918, p. 351.

- ↑ Griffith 1996, p. 145.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1991, pp. 268–269.

- 1 2 Times 1918, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ McCarthy 1995, p. 93.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1991, pp. 289, 293.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 269.

- ↑ Floyd 1920, p. 219.

- ↑ NP 2008.

- ↑ Kendall 2010, p. 217.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 279, 269, 276.

References

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-166-0.

- Floyd, Thomas H. (1920). At Ypres with Best-Dunkley. London: Bodley Head. OCLC 153690992. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Gibbs, Philip (1918). From Bapaume to Passchendaele, on the Western Front, 1917. New York, NY: George H. Doran. OCLC 1183503. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Griffith, P. (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack 1916–1918. London: Yale. ISBN 0-300-06663-5.

- Kendall, Paul (2010). Bullecourt 1917: Breaching the Hindenburg Line. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 0-7509-6252-6.

- Lupfer, T. (1981). The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (PDF). Fort Leavenworth: US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 227541165. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Martin, David (2014). Londoners on the Western Front: The 58th (2/1 London) Division in the Great War. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-4738-3468-6.

- McCarthy, C. (1995) [1993]. The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-217-0.

- Simpson, A. (2005) [2001]. The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (Spellmount ed.). London: London University. ISBN 1-86227-292-1. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- The Times History of the War (PDF). XVI. London: The Times. 1914–1921. OCLC 70406275. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "War hero pride of exhibition". Nottingham Post. Nottingham. 17 October 2008. OCLC 885338871. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-8371-5029-9.

Further reading

External links

- Wurst Farm, The British Postal Museum & Archive

- History of 58th (2/1st London) Division

- Pillbox fighting in the Ypres Salient, AWM