CNO cycle

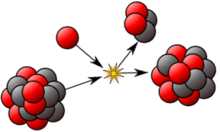

The CNO cycle (for carbon–nitrogen–oxygen) is one of the two known sets of fusion reactions by which stars convert hydrogen to helium, the other being the proton–proton chain reaction. Unlike the latter, the CNO cycle is a catalytic cycle. It is dominant in stars that are more than 1.3 times as massive as the Sun.[1]

In the CNO cycle, four protons fuse, using carbon, nitrogen and oxygen isotopes as catalysts, to produce one alpha particle, two positrons and two electron neutrinos. Although there are various paths and catalysts involved in the CNO cycles, all these cycles have the same net result:

- 4 1

1H

+ 2

e−

→ 4

2He

+ 2

e+

+ 2

e−

+ 2

ν

e + 3

γ

+ 24.7 MeV → 4

2He

+ 2

ν

e + 3

γ

+ 26.7 MeV

The positrons will almost instantly annihilate with electrons, releasing energy in the form of gamma rays. The neutrinos escape from the star carrying away some energy. One nucleus goes to become carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes through a number of transformations in an endless loop.

Theoretical models suggest that the CNO cycle is the dominant source of energy in stars whose mass is greater than about 1.3 times that of the Sun.[1] The proton–proton chain is more important in stars the mass of the Sun or less. This difference stems from temperature dependency differences between the two reactions; pp-chain reaction starts at temperatures around 4×106 K[2] (4 megakelvins), making it the dominant energy source in smaller stars. A self-maintaining CNO chain starts at approximately 15×106 K, but its energy output rises much more rapidly with increasing temperatures.[1] At approximately 17×106 K, the CNO cycle starts becoming the dominant source of energy.[3] The Sun has a core temperature of around 15.7×106 K, and only 1.7% of 4

He

nuclei produced in the Sun are born in the CNO cycle. The CNO-I process was independently proposed by Carl von Weizsäcker[4] and Hans Bethe[5] in 1938 and 1939, respectively.

Cold CNO cycles

Under typical conditions found in stars, catalytic hydrogen burning by the CNO cycles is limited by proton captures. Specifically, the timescale for beta decay of the radioactive nuclei produced is faster than the timescale for fusion. Because of the long timescales involved, the cold CNO cycles convert hydrogen to helium slowly, allowing them to power stars in quiescent equilibrium for many years.

CNO-I

The first proposed catalytic cycle for the conversion of hydrogen into helium was initially called the carbon–nitrogen cycle (CN cycle), also honorarily referred to as the Bethe–Weizsäcker cycle, because it does not involve a stable isotope of oxygen. Bethe's original calculations suggested the CN-cycle was the Sun's primary source of energy, owing to the belief at the time that the Sun's composition was 10% nitrogen;[5] the solar abundance of nitrogen is now known to be less than half a percent. This cycle is now recognized as the first part of the larger CNO nuclear burning network. The main reactions of the CNO-I cycle are 12

6C

→13

7N

→13

6C

→14

7N

→15

8O

→15

7N

→12

6C

:[6]

12

6C

+ 1

1H

→ 13

7N

+

γ

+ 1.95 MeV 13

7N

→ 13

6C

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 1.20 MeV (half-life of 9.965 minutes[7]) 13

6C

+ 1

1H

→ 14

7N

+

γ

+ 7.54 MeV 14

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 15

8O

+

γ

+ 7.35 MeV 15

8O

→ 15

7N

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 1.73 MeV (half-life of 122.24 seconds[7]) 15

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 12

6C

+ 4

2He

+ 4.96 MeV

where the carbon-12 nucleus used in the first reaction is regenerated in the last reaction. After the two positrons emitted annihilate with two ambient electrons producing an additional 2.04 MeV, the total energy released in one cycle is 26.73 MeV; it should be noted that in some texts, authors are erroneously including the positron annihilation energy in with the beta-decay Q-value and then neglecting the equal amount of energy released by annihilation, leading to possible confusion. All values are calculated with reference to the Atomic Mass Evaluation 2003.[8]

The limiting (slowest) reaction in the CNO-I cycle is the proton capture on 14

7N

. In 2006 it was experimentally measured down to stellar energies, revising the calculated age of globular clusters by around 1 billion years.[9]

The neutrinos emitted in beta decay will have a spectrum of energy ranges, because although momentum is conserved, the momentum can be shared in any way between the positron and neutrino, with either emitted at rest and the other taking away the full energy, or anything in between, so long as all the energy from the Q-value is used. All momentum which get the electron and the neutrino together is not great enough to cause a significant recoil of the much heavier daughter nucleus and hence, its contribution to kinetic energy of the products, for the precision of values given here, can be neglected. Thus the neutrino emitted during the decay of nitrogen-13 can have an energy from zero up to 1.20 MeV, and the neutrino emitted during the decay of oxygen-15 can have an energy from zero up to 1.73 MeV. On average, about 1.7 MeV of the total energy output is taken away by neutrinos for each loop of the cycle, leaving about 25 MeV available for producing luminosity.[10]

CNO-II

In a minor branch of the above reaction, that occurs in the Sun's core 0.04% of the time, the final reaction involving 15

7N

shown above does not produce carbon-12 and an alpha particle, but instead produces oxygen-16 and a photon and continues 15

7N

→16

8O

→17

9F

→17

8O

→14

7N

→15

8O

→15

7N

:

15

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 16

8O

+

γ

+ 12.13 MeV 16

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 17

9F

+

γ

+ 0.60 MeV 17

9F

→ 17

8O

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.76 MeV (half-life of 64.49 seconds) 17

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 14

7N

+ 4

2He

+ 1.19 MeV 14

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 15

8O

+

γ

+ 7.35 MeV 15

8O

→ 15

7N

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.75 MeV (half-life of 122.24 seconds)

Like the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen involved in the main branch, the fluorine produced in the minor branch is merely an intermediate product and at steady state, does not accumulate in the star.

CNO-III

This subdominant branch is significant only for massive stars. The reactions are started when one of the reactions in CNO-II results in fluorine-18 and gamma instead of nitrogen-14 and alpha, and continues 17

8O

→18

9F

→18

8O

→15

7N

→16

8O

→17

9F

→17

8O

:

17

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 18

9F

+

γ

+ 5.61 MeV 18

9F

→ 18

8O

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 1.656 MeV (half-life of 109.771 minutes) 18

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 15

7N

+ 4

2He

+ 3.98 MeV 15

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 16

8O

+

γ

+ 12.13 MeV 16

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 17

9F

+

γ

+ 0.60 MeV 17

9F

→ 17

8O

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.76 MeV (half-life of 64.49 seconds)

CNO-IV

Like the CNO-III, this branch is also only significant in massive stars. The reactions are started when one of the reactions in CNO-III results in fluorine-19 and gamma instead of nitrogen-15 and alpha, and continues 19

9F

→16

8O

→17

9F

→17

8O

→18

9F

→18

8O

→19

9F

:

19

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 16

8O

+ 4

2He

+ 8.114 MeV 16

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 17

9F

+

γ

+ 0.60 MeV 17

9F

→ 17

8O

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.76 MeV (half-life of 64.49 seconds) 17

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 18

9F

+

γ

+ 5.61 MeV 18

9F

→ 18

8O

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 1.656 MeV (half-life of 109.771 minutes) 18

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 19

9F

+

γ

+ 7.994 MeV

Hot CNO cycles

Under conditions of higher temperature and pressure, such as those found in novae and x-ray bursts, the rate of proton captures exceeds the rate of beta-decay, pushing the burning to the proton drip line. The essential idea is that a radioactive species will capture a proton before it can beta decay, opening new nuclear burning pathways that are otherwise inaccessible. Because of the higher temperatures involved, these catalytic cycles are typically referred to as the hot CNO cycles; because the timescales are limited by beta decays instead of proton captures, they are also called the beta-limited CNO cycles.

HCNO-I

The difference between the CNO-I cycle and the HCNO-I cycle is that 13

7N

captures a proton instead of decaying, leading to the total sequence 12

6C

→13

7N

→14

8O

→14

7N

→15

8O

→15

7N

→12

6C

:

12

6C

+ 1

1H

→ 13

7N

+

γ

+ 1.95 MeV 13

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 14

8O

+

γ

+ 4.63 MeV 14

8O

→ 14

7N

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 5.14 MeV (half-life of 70.641 seconds) 14

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 15

8O

+

γ

+ 7.35 MeV 15

8O

→ 15

7N

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.75 MeV (half-life of 122.24 seconds) 15

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 12

6C

+ 4

2He

+ 4.96 MeV

HCNO-II

The notable difference between the CNO-II cycle and the HCNO-II cycle is that 17

9F

captures a proton instead of decaying, and neon is produced in a subsequent reaction on 18

9F

, leading to the total sequence 15

7N

→16

8O

→17

9F

→18

10Ne

→18

9F

→15

8O

→15

7N

:

15

7N

+ 1

1H

→ 16

8O

+

γ

+ 12.13 MeV 16

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 17

9F

+

γ

+ 0.60 MeV 17

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 18

10Ne

+

γ

+ 3.92 MeV 18

10Ne

→ 18

9F

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 4.44 MeV (half-life of 1.672 seconds) 18

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 15

8O

+ 4

2He

+ 2.88 MeV 15

8O

→ 15

7N

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 2.75 MeV (half-life of 122.24 seconds)

HCNO-III

An alternative to the HCNO-II cycle is that 18

9F

captures a proton moving towards higher mass and using the same helium production mechanism as the CNO-IV cycle as 18

9F

→19

10Ne

→19

9F

→16

8O

→17

9F

→18

10Ne

→18

9F

:

18

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 19

10Ne

+

γ

+ 6.41 MeV 19

10Ne

→ 19

9F

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 3.32 MeV (half-life of 17.22 seconds) 19

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 16

8O

+ 4

2He

+ 8.11 MeV 16

8O

+ 1

1H

→ 17

9F

+

γ

+ 0.60 MeV 17

9F

+ 1

1H

→ 18

10Ne

+

γ

+ 3.92 MeV 18

10Ne

→ 18

9F

+

e+

+

ν

e+ 4.44 MeV (half-life of 1.672 seconds)

Use in astronomy

While the total number of "catalytic" nuclei are conserved in the cycle, in stellar evolution the relative proportions of the nuclei are altered. When the cycle is run to equilibrium, the ratio of the carbon-12/carbon-13 nuclei is driven to 3.5, and nitrogen-14 becomes the most numerous nucleus, regardless of initial composition. During a star's evolution, convective mixing episodes moves material, within which the CNO cycle has operated, from the star's interior to the surface, altering the observed composition of the star. Red giant stars are observed to have lower carbon-12/carbon-13 and carbon-12/nitrogen-14 ratios than do main sequence stars, which is considered to be convincing evidence for the operation of the CNO cycle.

See also

- Stellar nucleosynthesis, the whole topic

- Triple-alpha process, how 12

C

is produced from lighter nuclei

References

- 1 2 3 Salaris, Maurizio; Cassisi, Santi (2005), Evolution of stars and stellar populations, John Wiley and Sons, pp. 119–121, ISBN 0-470-09220-3

- ↑ Reid, I. Neill; Suzanne L., Hawley (2005), New light on dark stars: red dwarfs, low-mass stars, brown dwarfs, Springer-Praxis books in astrophysics and astronomy (2nd ed.), Springer, p. 108, ISBN 3-540-25124-3

- ↑ Schuler, S. C.; King, J. R.; The, L.-S. (2009). "Stellar Nucleosynthesis in the Hyades Open Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 701 (1): 837–849. arXiv:0906.4812

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...701..837S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/701/1/837.

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...701..837S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/701/1/837. - ↑ von Weizsäcker, C. F. (1938). "Über Elementumwandlungen in Innern der Sterne II". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 39: 633–46.

- 1 2 Bethe, H. A. (1939). "Energy Production in Stars". Physical Review. 55 (5): 434–56. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..434B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.434.

- ↑ Krane, K. S. (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 537. ISBN 0-471-80553-X.

- 1 2 Principles and Perspectives in Cosmochemistry, Springer, 2010, ISBN 9783642103681, page 233

- ↑ Wapstra, Aaldert; Audi, Georges (18 November 2003). "The 2003 Atomic Mass Evaluation". Atomic Mass Data Center. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ LUNA Collaboration; Lemut, A.; Bemmerer, D.; Confortola, F.; Bonetti, R.; Broggini, C.; Corvisiero, P.; Costantini, H.; Cruz, J.; Formicola, A.; Fülöp, Zs.; Gervino, G.; et al. (2006). "First measurement of the 14N(p,gamma)15O cross section down to 70 keV". Physics Letters B. 634: 483–487. arXiv:nucl-ex/0602012

. Bibcode:2006PhLB..634..483L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2006.02.021.

. Bibcode:2006PhLB..634..483L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2006.02.021. - ↑ Scheffler, Helmut; Elsässer, Hans (1990). Die Physik der Sterne und der Sonne. Bibliographisches Institut (Mannheim, Wien, Zürich). ISBN 3-411-14172-7.

Further reading

- Bethe, H. A. (1939). "Energy Production in Stars". Physical Review. 55 (5): 434–56. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..434B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.434.

- Iben, I. (1967). "Stellar Evolution Within and off the Main Sequence". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 5: 571. Bibcode:1967ARA&A...5..571I. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.05.090167.003035.