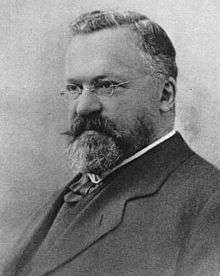

Carl Swartz

| Carl Swartz | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Prime Minister of Sweden | |

|

In office 30 March 1917 – 19 October 1917 (203 days) | |

| Monarch | Gustaf V |

| Preceded by | Hjalmar Hammarskjöld |

| Succeeded by | Nils Edén |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Carl Johan Gustaf Swartz 5 June 1858 Norrköping, Östergötland County |

| Died |

6 November 1926 (aged 68) Stockholm |

| Political party | National Party |

| Alma mater |

Uppsala University, University of Bonn |

Carl Johan Gustaf Swartz (5 June 1858 – 6 November 1926) was a Swedish right-wing politician who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 30 March 1917 to 19 October 1917.[1] He also served as Minister for Finance from 1906 to 1911. He married Dagmar Lundström in 1886, with whom he had three children, Erik, Brita and Olof.

Life and career

Carl Swartz was born on 5 June 1858 in Norrköping, Östergötland County, the son of factory-owner Erik Swartz and wife Elisabeth Forsgren. After completing studies in Uppsala and Bonn, he returned to Norrköping to run the family business, tobacco producers Petter Swartz. He came to play a large role in his home town, not least culturally. He was Chairman of the Board of Directors of, amongst others, Sweden's private Central Bank between 1912 and 1917. In 1917, he became the national university chancellor.

As Minister for Finance between 1906 and 1911, he implemented a number of reforms including integrated income- and property tax, which both became progressive. With the amalgamation of the right-wing groups of the Riksdag's lower chamber, Swartz became a member of the inner council of the newly formed Nationella Partiet (English: The National Party) in 1912.

World War I

During World War I he was a key figure in the Riksdag in his capacity as Chairman of the Standing Committee of Supply between 1915 and 1917. With the fall, due to external pressures and internal disharmony, of the government of non-party aligned Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, King Gustav V called on the party-political conservative Swartz to become Prime Minister. He accepted the appointment more out of a sense of duty rather than personal desire for the office. The new government's foremost task was to exercise a calming influence on the bourgeois which was worried, in anticipation of May 1, 1917, by rumours that the February Revolution in Russia would spread to Sweden.

Swartz was generally considered as a moderate and reasonable conservative, in the style of an old-fashioned and thoughtful mill-owner. He forbade private bourgeois militias in advance of the 1 May 1917 demonstrations, in return for the Social Democratic Party's assurance that they would be responsible for maintaining order. Without this political concession, the confrontations could have escalated during the month of May and resulted in a domestic political crisis.

Discontent stemmed mainly from the fact that the people were living on the brink of starvation. Hunger riots, rather than the political demand for voting rights, lay behind the demonstrations. The situation calmed with the beginning of the potato harvest in early summer. Swartz also quickly concluded negotiations with the Triple Entente powers, principally Great Britain, on imports from the west, which Hammarskjöld had prevented.

The Social Democrats used the hunger riots to put pressure on the right-wing government, with demands such as universal suffrage, women's suffrage and removal of the 40-degree voting scale in municipal elections. The government was divided on these issues. Leader of the left-wing faction, Minister for Civil Affairs Oscar von Sydow and Minister for Finance Conrad Carleson agreed with the Social Democrats' and Liberals' proposals. They threatened to resign if Swartz agreed with Minister for Foreign Affairs Arvid Lindman's demand to maintain the status quo. The Minister for Finance was backed by the industry, which wanted an end to the debacle. Swartz was irresolute and felt under pressure from his opponents and his solution was to wait for the spring election. This action was historic: he became the first leading conservative to follow the parliamentary principle that the people - not the king - should choose the government.

Gustav V attempted for a long time to avoid a breakthrough for parliamentarianism, but his wish to allow Swartz to continue, despite the left-wing parties' success in the 1917 election was undermined by the involvement of Swartz's son in a black marketeering scandal, a violation of existing rationing.

Reputation, legacy and death

Carl Swartz was also an eminent municipal figure and a generous philanthropist. In 1912, he donated Villa Swartz to the town of Norrköping, as accommodation for a library and museum. He died in Stockholm on 6 September 1926.

References

| Preceded by Elof Biesèrt |

Swedish Minister for Finance 1906 – 1911 |

Succeeded by Theodor Adelswärd |

| Preceded by Hjalmar Hammarskjöld |

Prime Minister of Sweden March – October 1917 |

Succeeded by Nils Edén |