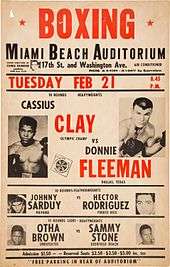

Cassius Clay vs. Donnie Fleeman

Cassius Clay (soon Muhammad Ali) fought an eight-round boxing match with Texan Donnie Fleeman in Miami on February 21, 1961. Prior to this fight, Fleeman had a record of 51 fights with 45 wins including 20 knockouts. Clay won the bout through a technical knockout after the referee stopped the fight in the seventh round. This was the first time Clay had gone over six rounds in a boxing match. It was also the first time Fleeman had ever been knocked down in a boxing match. Fleeman retired from boxing after this fight.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Background

Before this fight, Fleeman had fought with Ezzard Charles and Sonny Liston in boxing matches, winning against Charles, and losing to Liston.[4][10] Of his encounter with Liston, Fleeman later recalled that he had gone backstage waiting for his fight when he noticed a huge man sitting next to him.

I didn't know who he was except he was a monster, and I felt sorry for whoever was going to fight him. Then I go out to see my opponent. It was him [Liston]. I lost that fight sitting beside him...I was never knocked out. But Sonny Liston hit me so hard that if I had not got tangled up in the ropes, I would have been knocked out.[11]

Prior to the Clay–Fleeman bout, it was held that Fleeman's experience and durability gave him an edge over Clay.[3]

Buildup

Fleeman had injured himself in his previous boxing match. Nevertheless, the guaranteed prize money for the Clay–Fleeman fight was an offer he could not refuse, particularly after his wife encouraged him to go on with the fight since they needed the money.[4][12] Fleeman later explained:

I had fought Pete Rademacher before [the Clay–Fleeman bout]. He had fractured my sternum. My doctor said I should not fight. I could barely raise my left arm. But I had a guarantee of $3,000. So I went ahead and fought.[12]

In interviews with the local newspapers Clay stated that "I plan to be heavyweight champion someday. If I can't beat this fellow, I ought to change my plans."[3] As was his usual practice before almost every Clay/Ali fight, Angelo Dundee announced that Clay would face his toughest test in the upcoming fight.[7]

The fight

Although Fleeman was extremely durable and tough, Clay's speed overwhelmed the Texan in the fight.[2][3][7]

Straight-ahead guys like the slow Texan, who rarely took a step backwards or laterally, were made to order for Clay.[7]

Fleeman was able to absorb Clay's punches during the bout, and would have probably gone the full distance, but for the fact that he was badly cut around both his eyes, and his nose had started bleeding, due to which the referee stopped the fight in the seventh round.[3][9]

Reflecting on the fight, Fleeman observed that Clay's arms were long and fast, and that he had felt as if he was a punching bag.[5] Fleeman would also note that, despite the injury he had carried into the fight,

I'm not taking anything away from Cassius. He was quick and after seven rounds, I quit. That was the only fight when I was ready to get out of the ring.[12]

Aftermath

After the fight, Clay struck a Tarzan of the Apes pose in the dressing room and, with clenched fists and glaring eyes, intoned, "He had to go."[13] Clay then noticed a reporter he had met in Rome in 1960 who had witnessed Clay's bout with Zbigniew Pietrzykowski for the Olympic Light Heavyweight Championship. Clay told the reporter: "Hey, write about me. You ain't wrote about me since Rome."[13]

Angelo Dundee brought some literary figures to interact with Clay after the boxer had taken a shower. Dundee later recalled what happened next:

[The fight] with Fleeman was at the start of spring training, and so some of the heavyweights of the literary field—Shirley Povich, Doc Greene, Al Buck, Dick Young, Jimmy Cannon—were down here with time on their hands. They were friends of mine and I wanted to show my fighter off...[Ali] had won. But the writers weren't that sold on him as a fighter—they thought he bounced around too much and did everything wrong. They figured he was all mouth and no talent. This was still an era when fighters thought they needed nine guys to talk for them. Joe Louis used to say, "My manager does my talking for me. I do my talking in the ring." Marciano was somewhat like that, too. But Muhammad was different right off the bat, and I thought it was great. So Muhammad waited for them to take their pads out. "Aren't you gonna talk to me? Aren't you gonna talk to me?" And so he wore them down. They started to listen.[14]

Long after Fleeman's retirement from boxing, writer Jon McConal visited the boxer at Fleeman's residence in Ellis County.McConal reports that at this time Fleeman was "still lean and looked like a fighter despite being in his late sixties."[11]However, at the time he died, aged 80, Fleeman was suffering from Alzheimer's, and also from what Clay/Ali developed in later years: Parkinson's.[5]

References

- ↑ "Muhammad Ali's ring record". ESPN. 19 November 2003. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- 1 2 Thomas Hauser (1991). Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times. Simon & Schuster. p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Felix Dennis and Don Atyeo (2003). Muhammad Ali: The Glory Years. miramax books. p. 54.

- 1 2 3 "Sherrington: Late Dallas boxer Donnie Fleeman could hit like a mule". SportsDay. March 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Daughter of local boxer remembers rare connection to boxing great Muhammad Ali". Fox News. 4 June 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ David Remnick (1998). King of the World. Random House. pp. 115–6.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael Ezra (2009). Muhammad Ali:The Making of an Icon. Temple University Press. p. 30.

- ↑ Jon McConal (2009). Jon McConal's Texas. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 29–32.

- 1 2 Jose Torres (2009). Sting like a bee: The Muhammad Ali story. TBS The Book Service Ltd. p. 103.

- ↑ Jon McConal (2009). Jon McConal's Texas. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 30–2.

- 1 2 Jon McConal (2009). Jon McConal's Texas. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 30–1.

- 1 2 3 Jon McConal (2009). Jon McConal's Texas. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 31.

- 1 2 "Ali story tops 'em all". The Spokesman-Review. 24 December 1981. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ↑ David Remnick (1998). King of the World. Random House. p. 116.