Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire

| His Grace The Duke of Devonshire KG MC PC DL | |

|---|---|

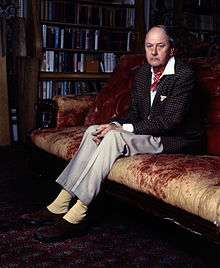

Portrait by Allan Warren | |

| Minister of State for Commonwealth Relations | |

|

In office 1962–1964 | |

| Prime Minister |

Harold Macmillan Sir Alec Douglas-Home |

| Preceded by | Lord Alport |

| Succeeded by | Cledwyn Hughes |

| Under-Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations | |

|

In office 1960–1962 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Richard Thompson |

| Succeeded by | John Tilney |

| Member of the House of Lords as Duke of Devonshire | |

|

In office 26 November 1950 – 11 November 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Edward Cavendish |

| Succeeded by | House of Lords Act 1999 |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

2 January 1920 London, England |

| Died |

3 May 2004 (aged 84) Chatsworth, Derbyshire |

| Political party |

UKIP[1] (2001–2004) None (1987–2001) Social Democratic (1981–87) Conservative (1950–81) National Liberal (1940s) |

Andrew Robert Buxton Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire, KG, MC, PC, DL (2 January 1920 – 3 May 2004), styled Lord Andrew Cavendish until 1944 and Marquess of Hartington from 1944 to 1950, was a British Conservative and later Social Democratic Party politician. He was a minister in the government of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (who was married to his aunt), but is best known for opening Chatsworth House to the public.

Early life

Cavendish was born to Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire and Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, the former Mary Alice Gascoyne-Cecil, daughter of James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury. He was educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge.

Career

Military service

Cavendish served in the British Army during World War II. Having attended an Officer Cadet Training Unit, he was commissioned into the Coldstream Guards as a second lieutenant on 2 November 1940.[2] On 7 December 1944, while holding the rank of acting captain, he was awarded the Military Cross 'in recognition of gallant and distinguished services in Italy'.[3] The action took place on 27 July 1944 when his company was cut off for 36 hours in heavy combat near Strada, Italy. He held the rank of major at the end of the war.

In later life, he took on a number of honorary positions within the military. On 2 December 1953, he was appointed Honorary Colonel of a Territorial Army unit of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.[4] On 2 October 1981, he was appointed Honorary Colonel of the Manchester and Salford Universities Officers' Training Corps.[5] He relinquished this appointment on 2 January 1985.[6]

Political career

Cavendish ran unsuccessfully as a National Liberal candidate for Chesterfield in the 1945 general election and as a Conservative for the same seat in 1950. He was Mayor of Buxton from 1952 to 1954. He served as Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Commonwealth Relations from 1960 to 1962, Minister of State at the Commonwealth Relations Office from 1962 to 1963, and for Colonial Affairs from 1963 to 1964. He once said that these appointments by his uncle, Harold Macmillan, the then-prime minister, were "the greatest act of nepotism ever".[7][8]

He joined the Social Democratic Party shortly after its foundation in 1981, but left the party when David Owen resigned as the party's leader in 1987, describing Owen as "the best of them".[9] He then sat as a crossbencher during his rare appearances in the House of Lords.[10][11]

Other pursuits

The duke followed the family tradition of owning racehorses, the most famous of which was Park Top, the subject of the duke's first published book, A Romance of The Turf: Park Top, which was published in 1976. His autobiography, Accidents of Fortune, was published just before his death in 2004. The duke had many disputes over the years with the ramblers who used the paths near Chatsworth. Eventually though, in 1991, he signed an agreement with the Peak National Park Authority opening 1,300 acres (5 km²) of his estate to walkers. He said that everyone was "welcome in my back garden". The duke's real estate holdings were vast. In addition to Chatsworth he also owned Lismore Castle in Ireland and Bolton Abbey in North Yorkshire. He also owned the bookshop Heywood Hill and the gentleman's club Pratt's.

He was a major collector of contemporary British art, known especially for his patronage of Lucian Freud. He was one of the founders, and the chief patron of, the Next Century Foundation, in which capacity he hosted the private Chatsworth talks between representatives of the governments of the Arab World and Israel. The duke was listed at number 73 in the Sunday Times Sunday Times Rich List of the richest people in Great Britain in 2004.

Family

Marriage

In 1941 Cavendish married the Hon. Deborah Mitford (31 March 1920 – 24 September 2014), one of the Mitford sisters.

The marriage was not without some bumps. Three of the couple's six children died soon after birth, and the Duke's extramarital affairs became public after he appeared as a witness at a burglary trial and was forced to admit, under oath, that he was on holiday with one of a series of younger women when the crime occurred at his London home. The Duke, however, claimed that much of his marriage's success was due to the Duchess's tolerance and broadmindedness. The Duchess, as chatelaine, was largely responsible for the success of Chatsworth as a commercial endeavour.

Issue

Cavendish and his wife had six children, three of whom died in infancy.[12] The three surviving children were a son, Peregrine Cavendish, 12th Duke of Devonshire, and two daughters, Lady Emma Cavendish and Lady Sophia Topley.

- Mark Cavendish (born and died 14 November 1941)

- Lady Emma Cavendish (26 March 1943) she married Hon. Tobias Tennant, son of Christopher Grey Tennant, 2nd Baron Glenconner on 3 September 1963. They have three children and ten grandchildren:

- Isabella Tennant (28 June 1964) she married Piers Hill, son of Simon Hill, on 9 August 1997. They have three children:

- Rosa Hill

- Victor Hill

- Lily Hill

- Edward Tobias Tennant (30 March 1967) he married Emma Bridgeman in 2000. They have three children:

- Harry Tobias Tennant (7 September 2001)

- Georgia Rose Tennant (9 July 2003)

- Isla May Tennant (8 August 2006)

- Stella Tennant (17 December 1970) she married David Lasnet on 22 May 1999. They have four children.

- Isabella Tennant (28 June 1964) she married Piers Hill, son of Simon Hill, on 9 August 1997. They have three children:

- Peregrine Cavendish, 12th Duke of Devonshire (27 April 1944) he married Amanda Heywood-Lonsdale on 28 June 1967. They have three children and eight grandchildren.

- Lord Victor Cavendish (born and died 22 May 1947)

- Lady Mary Cavendish (born and died 5 April 1953)

- Lady Sophia Louise Sydney Cavendish (18 March 1957) she married Anthony Murphy on 20 October 1979 and they were divorced in 1987. She remarried Alastair Morrison, 3rd Baron Margadale on 19 July 1988 and they were divorced. They have two children. She remarried again William Topley on 25 November 1999.

In December 1946, the Duchess had a miscarriage; had the child been born, it would have been a twin of Victor Cavendish, born in 1947.[13]

Inheritance

Cavendish's older brother William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington, who would have inherited the dukedom, was killed in combat near the end of the war. With William's death, Andrew became heir and received the courtesy title of Marquess of Hartington, which he held from 1944 until 1950.

Cavendish's uncle, Lord Charles Cavendish, died aged 38 as a result of alcoholism.[14] Lord Charles's will bequeathed Lismore Castle to Andrew upon the remarriage of Charles's wife, Adele Astaire, in 1947.[14]

The 10th Duke died of a heart attack while visiting Eastbourne in November 1950 and Andrew, who was in Australia at the time, inherited the title.[7] The Duke died while being attended by suspected serial killer Dr John Bodkin Adams, who was his doctor when visiting Eastbourne. No proper police investigation was ever conducted into the death but Cavendish later said "it should perhaps be noted that this doctor was not appointed to look after the health of my two younger sisters, who were then in their teens";[7] Adams had a reputation for grooming older patients to extract bequests.

Cavendish inherited the estate but also an inheritance tax bill of £7 million (£216 million in 2015), nearly 80 per cent of the value of the estate.[15][16] To meet this, the Duke had to sell off many art objects and antiques, including several Rembrandts, Van Dycks and Raffaello Santis, as well as thousands of acres of land.[16]

The Duke is buried in the churchyard of St Peter's Church, Edensor - in the grounds of Chatsworth.

Honours

In 1996 he was made a Knight of the Garter.

Other

He once told an interviewer:

"Wonderful things have happened in my life — it's time my son had his turn. When I was young I used to like casinos, fast women and God knows what. Now my idea of Heaven, apart from being at Chatsworth, is to sit in the hall of Brooks's, having tea."

Ancestry

Patrilineal descent

- Robert de Gernon, Norman nobleman, ca 1066

- Matthew de Gernon, ca 1100

- Ralph de Gernon, ca 1130–1167

- Ralph de Gernon, Sheriff of Dorset, 1160–1248

- William de Gernon, Marshal of the King's Household, 1187–1258

- Geoffrey de Gernon, ?-?

- Roger de Gernon, ca 1324, married the daughter of John Potton of Cavendish and his descendants took surname "Cavendish"

- Sir John Cavendish, ca 1346–1381 Treasurer, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge.

- John Cavendish, ?-?

- William Cavendish, d. 1433

- Thomas Cavendish, d. 1477

- Thomas Cavendish, d. 1523

- Sir William Cavendish, Treasurer of the Exchequer, 1505–1557

- William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire (1552–1626)

- William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire (1591–1628)

- William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire (1617–1684)

- William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire (1640–1707) was created Duke of Devonshire in 1694

- William Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Devonshire (1673–1729)

- William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire (1698–1755)

- William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire (1720–1764)

- George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington (1754–1834)

- William Cavendish (1783–1812)

- William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire (1808–1891)

- Lt.-Col. Lord Edward Cavendish (1838–1891)

- Victor Christian William Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire (1868–1938)

- Edward William Spencer Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire (1895–1950)

- Andrew Robert Buxton Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire (1920–2004)

Bibliography

- writing as The Duke of Devonshire: A Romance of the Turf: Park Top (2000 edition ISBN 0-7195-5482-9)

- writing as Andrew Devonshire: Accidents of Fortune [Autobiography] (2004) ISBN 0-85955-286-1

References

- ↑ Johnson, Frank (19 June 2004). "Notebook". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

[...] the three dukes among Ukip's patrons – Somerset, Rutland and the late Devonshire, as well as the Earl of Bradford and Lord Neidpath, heir to the earldom of Wemyss [...]

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 34995. p. 6621. 15 November 1940. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36828. pp. 5609–5610. 5 December 1944. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40064. p. 152. 1 January 1954. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 48776. p. 13608. 26 October 1981. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 50026. p. 1621. 4 February 1985. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Pamela V. Cullen A Stranger in Blood: The Case Files on Dr John Bodkin Adams, London, Elliott & Thompson, 2006, ISBN 1-904027-19-9

- ↑ Graham Stewart Nepotism on a majestic scale, The Times, 2 February 2008. Accessed 27 March 2008.

- ↑ Barber, Lynn (20 October 2002). "The original Thin White Duke". The Observer. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- ↑ Barker, Dennis (5 May 2005). "Obituary: The Duke of Devonshire". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- ↑ "Obituary: The Duke of Devonshire". BBC News. 4 May 2004. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- ↑ Deborah Mitford, Duchess of Devonshire, Wait for Me! (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2010), pages 128–132

- ↑ Deborah Mitford, Duchess of Devonshire, Wait for Me! (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2010), pages 130

- 1 2 Deborah Devonshire (15 September 2011). All in One Basket. John Murray. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-1-84854-594-6.

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- 1 2 Keith Colquhoun; Ann Wroe (2008). Economist Book of Obituaries. Profile Books. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-1-84765-041-2.

External links

- Daily Mail Interview with ex-prostitute Norma Levy about Lord Lambton scandal et al.

- Generations Reaching – on a delightful chance meeting with the late 11th Duke of Devonshire, and with Kathleen Agnes Kennedy and John F. Kennedy beside Lismore Castle, Co Waterford, Ireland in mid-May 2004. (chp.8 A feeling of homecoming – mythic content)

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Duke of Devonshire

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Richard Thompson |

Under-Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations jointly with Bernard Braine 1961–1962 John Tilney 1962 1960–1962 |

Succeeded by John Tilney |

| Preceded by Cuthbert Alport |

Minister of State for Commonwealth Relations 1962–1964 |

Succeeded by Cledwyn Hughes |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by Edward Cavendish |

Duke of Devonshire 1950-2004 |

Succeeded by Peregrine Cavendish |