Cell division orientation

Cell division orientation is the direction along which the new daughter cells are formed. Cell division orientation is important for morphogenesis, cell fate and tissue homeostasis. Abnormalities in the cell division orientation leads to the malformations during development and cancerous tissues. Factors influenced the cell division orientation are cell shape, anisotropic localization of specific proteins and mechanical tensions.

Implication for morphogenesis

Cell division orientation is one of the mechanisms that shapes tissue during development and morphogenesis. Along with cell shape changes, cell rearrangements, apoptosis and growth, oriented cell division modifies the geometry and topology of live tissue in order to create new organs and shape the organisms. Reproducible patterns of oriented cell divisions were described during mophogenesis of Drosophila embryos, Drosophila pupa,[1] zebrafish embryos[2] and mouse early embryos. Oriented cell divisions contribute to the tissue elongation and the release of mechanical stress. While in the first case oriented cell division akts as active contributor to the morphogenesis, the latter case is a passive response to the external mechanical tensions.[3]

Implication for tissue homeostasis

In several tissues, such as columnar epithelium, the cells divide along the plane of the epithelium. Such divisions insert new formed cells in the epithelium layer. The disregulation of the orientation of cell divisions result in the creation of the cell out of epithelium and is observed at the initial stages of cancer.

Regulation

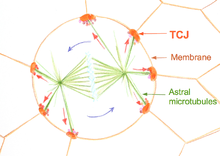

More than a centure ago Oskar Hertwig proposed that the cell division orientation is determined by the shape of the cell (1884), known as Hertwig rule.[4] In the epithelium the cells 'reads' its shape through the specific cell junction called tricellular junctions (TCJ). TCJ provide mechanical and geometrical clues for the spindle apparatus to ensure that cell divide along its long axis.[5] Several factors could regulate cell shape and therefore orientation of cell division. Among these factors is the anisotropic mechanical stress. This stress could be the result of the external mechanical deformation of generated intracellularly by non-isotropic localization of specific proteins.

References

- ↑ Guirao, Rigaud, Bosveld, Bailles, Lopez-Gay, Ishihara, Sugimura, Graner, Bellaïche (2016). "Unified quantitative characterization of epithelial tissue development.". eLife: e08519. doi:10.7554/eLife.08519.

- ↑ Campinho, Behrndt, Ranft, Risler, Minc, Heisenberg (2013). "Tension-oriented cell divisions limit anisotropic tissue tension in epithelial spreading during zebrafish epiboly.". Nature Cell Biology. 15 (12): 1405.

- ↑ Ranft, Basan, Elgeti, Joanny, Prost, Jülicher (2010). "Fluidization of tissues by cell division and apoptosis.". PNAS. 107 (49): 20863–20868. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011086107.

- ↑ Hertwig O (1884). "Das Problem der Befruchtung und der Isotropie des Eies. Eine Theorie der Vererbung.". Jenaische Zeitschrift fur Naturwissenschaft. 18: 274.

- ↑ Bosveld F, Markova O, Guirao B, Martin C, Wang Z, Pierre A, Balakireva M, Gaugue I, Ainslie A, Christophorou N, Lubensky DK, Minc N, Bellaïche Y (2016). "Epithelial tricellular junctions act as interphase cell shape sensors to orient mitosis.". Nature. 25 (530): 496–8. doi:10.1038/nature16970. PMID 26886796.