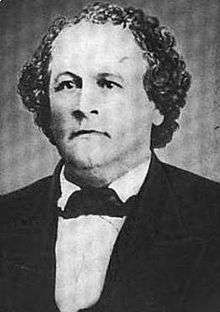

Charles H. Constable

| Charles H. Constable | |

|---|---|

| |

| Judge of the Illinois 4th Circuit Court | |

|

In office July 1, 1861 – October 9, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Justin Harlan |

| Succeeded by | Oliver L. Davis |

| Member of the Illinois Senate from the Wabash County district | |

|

In office 1844–1848 | |

| Preceded by | Rigdon B. Slocumb |

| Succeeded by | John A. Campbell |

| Illinois Constitutional Delegate from Wabash County, Illinois | |

|

In office 1847–1847 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 17, 1817 Harford County, Maryland |

| Died |

October 9, 1865 (aged 48) Effingham, Illinois |

| Resting place | Marshall, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Martha Hinde |

| Relations |

|

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | University of Virginia |

| Occupation | |

| Religion | Methodist Episcopal Church |

| Signature |

|

Charles H. Constable (July 17, 1817 – October 9, 1865) was an American attorney, Illinois State Senator, judge, and real estate entrepreneur. He was raised in Maryland and graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in Law. After settling in Illinois, he married the oldest daughter of Thomas S. Hinde, a pioneer and real estate developer. Initially, he practiced law in Mount Carmel, Illinois, the town founded by Hinde. He managed the business and real estate affairs of his father-in-law until Hinde died in 1846.

Later, Constable was active in Illinois politics and for a time was a close friend of Abraham Lincoln. During his life Constable was a one-term Illinois State Senator, a delegate to the Illinois Constitutional Convention, and a one-term Circuit Court Judge. One source described Constable at the time of the Matson slave case to be "the best educated lawyer at the bar." He is most commonly remembered for his decision to allow four Union deserters to go free during the Civil War. This decision led to Constable's arrest by Union military leaders and a trial in federal court. Constable argued that legal precedent supported his decision, and all charges were dropped in Federal court.

Following the dismissal of charges and his return to the bench, Constable and his family endured repeated threats, violence, and humiliation at the hands of partisan mobs angry at his release of the Civil War deserters. Not long after his release, Constable developed an addiction to morphine, then available over the counter. He died at the age of 48 from an overdose of the drug. One source stated the morphine overdose was a suicide. His wife, Martha Hinde Constable, died shortly after he did.

Early years

Charles Constable was born and raised in Maryland. He attended Bel Air High School, which was a scientific and classical school in Harford County, Maryland. Later he enrolled and graduated from the University of Virginia with high honors.[1] In 1838, he moved to Mount Carmel, Illinois, and shortly thereafter he married Martha Hinde.[2] Martha was the daughter of Thomas S. Hinde, a noted attorney, Methodist minister, real estate entrepreneur, writer, and the founder of Mount Carmel.

Thomas S. Hinde died early in 1846, followed soon by his wife. Martha and her husband took over the care of her younger orphaned siblings, Edmund, Charles, and Belinda Hinde. In the diaries of his nephew, Constable and his wife were described as good and honest people, and they cared for many relatives and friends in their household through the years.[3] During this time, Constable practiced law in Mount Carmel, and sold town lots in Mount Carmel that had been owned by his father-in-law before his death.

After Hinde's death, Constable quickly gathered all of his writings, diaries, business documents, and miscellaneous other items and donated them to Lyman Draper in 1864, who was known for collecting the papers of figures of the Trans-Allegheny frontier. Because of this donation, many scholars and historians have been able to study these papers.[4] The Thomas S. Hinde documents are owned and kept at the Wisconsin Historical Society.[5]

Early political career

For a short time after the death of Thomas S. Hinde, Constable remained in Mount Carmel with his wife and extended family. He was elected to the Illinois Senate in 1844 and was a delegate for Wabash County, Illinois, to the Illinois constitutional convention.[6] As a member of the Illinois Constitutional Convention, he made substantial contributions during the negotiations and drafting of the Illinois Constitution. He was selected as chairman of the committee to prepare the address about the constitution to the citizens of Illinois.[7] During this time, Constable and Lincoln became close friends; Lincoln is quoted as calling Constable, "my esteemed friend."[8] In 1850 in Peoria, Illinois, Constable was elected Grand Patriarch of the Odd Fellows.[9]

Matson slave case

In 1847, Abraham Lincoln defended Robert Matson, a slave owner who was trying to retrieve his fugitive slaves. Matson had brought the slaves from his Kentucky plantation to work on land he owned in Illinois.[10] The slaves were represented by Orlando Ficklin, Usher Linder, and Charles H. Constable.[11] The slaves ran away while in Illinois and believed that they were free, knowing that the Northwest Ordinance forbade slavery in Illinois. In this case, Lincoln invoked the right of transit, which allowed slave holders to take their slaves temporarily into free territory. Lincoln also stressed that Matson did not intend the slaves to remain permanently in Illinois.

Even with these arguments, the judge in Coles County ruled against Lincoln, and the slaves were set free.[12] This was part of a principle "once free, always free," which was adopted in Illinois and other free states. One source described Constable at the time of the Matson slave case to be "the best educated lawyer at the bar."[13]

Attempted government appointments

According to one source, after Zachary Taylor was elected president in 1848, Constable wrote to Lincoln and David Davis seeking a political appointment to a Latin American country as a chargé d'affaires, because of his growing family and declining law practice. Even though both Lincoln and Davis wrote letters in support of Constable, he did not receive any appointments.[14] In January 1851, Lincoln wrote a letter to Senator James Pearce recommending Constable be nominated for an Oregon federal judgeship. [15] Constable was not gain this appointment.

Around 1848, he moved with his family to Marshall, Illinois, and ran unsuccessfully for circuit court judge that same year. In 1858, Constable ran in a special election to fill a vacant seat of the Illinois Supreme Court, but was defeated by Pinckney H. Walker by a vote margin of 229 votes to 95.[16] Constable ran again in 1861 and was elected as a state circuit court judge of the Illinois 4th circuit.[17]

Change of political parties

Originally, Constable was a member of the Whig party, likely due to the close friendship of his father-in-law and Henry Clay.[18] Due mainly to frustrations over how the Whig party had treated him, Constable decided to switch parties. He is quoted as saying, "that the party was dominated by old fogies who are indifferent to younger men."[19] His inclination toward the Democratic Party almost led to a fistfight between himself and Lincoln in a tavern in Paris, Illinois. Lincoln was quoted as saying, "Mr. Constable, I understand you perfectly, and have noticed for some time that you have been slowly and cautiously picking your way over to the Democratic party."[14] After this heated exchange, the men reconciled, but by 1856 Lincoln claimed that Constable had left the party.[20] In 1858, Constable was the Illinois elector at-large for the election of President James Buchanan, a Democrat.[21]

In 1861, Constable was elected judge on the Democratic ticket of the Illinois fourth circuit. This led to a falling out between Lincoln and Constable. On several occasions while Lincoln was President, Constable repudiated him in front of large crowds.[20] During a rally of more than 40,000 people in Springfield, Illinois, Constable was elected to a leadership position of an organization set up to oppose Lincoln's policies.[22]

Civil War arrest

During the Civil War, Constable ordered that four Union deserters be released from military custody, arguing that the Union soldiers had no right to arrest the deserters in the sovereign state of Illinois. Shortly thereafter, Colonel Henry B. Carrington, commander of the Indiana Military District, was sent to Marshall. He arrested Constable, appearing while court was in session and surrounding the courthouse with over 200 Union soldiers. [23] Carrington believed the Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society said to be supporting the South, was responsible for the release of the deserters.

Worried about potential violence, he believed that he needed the troops to support his rescue of the Union soldiers who had been ordered by Constable to be arrested for kidnapping the deserters.[24] But, there was little to no resistance, and Constable invited Carrington to have dinner at his home before they left for Indianapolis.[25] Constable's arrest and ruling resulted in widespread condemnation—even Richard W. Thompson thought Constable's ruling was "illegal and arbitrary"—and eventually led to his trial.[26] After being heard by Judge Samuel H. Treat of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Illinois on April 7, 1863, Constable was released and the charges were dismissed.[27] The case is still noted by legal scholars and historians as an example of the military interfering in civilian courts.[28]

Treatment after dismissal of charges

After Constable was released from custody and returned to his home in Marshall, he was ostracized by many members of the public, who thought he had acted against the Union. One account states that Constable received death threats, threats to burn his house, and threats to kill his children.[3] The arrest triggered a riot in Charleston, Illinois, commonly referred to as the Charleston Riot.[29] During the riot:

[Two small boys] saw Judge Constable, white and trembling, in an angle of the wall in the alley to their right, evidently uncertain what to do or where to go next. How a man of his portly form could have vacated the Judge's bench, come down from the court room, and got there so soon after the firing began never ceased to be a wonder to those boys.[30]

In January 1864, Union soldiers forced Constable under threat of violence to make an oath of allegiance to the federal government in Mattoon, Illinois.[31] One source described the Union soldiers as a "mob" and stated that Constable "shed tears."[32] Another source stated that the soldiers violently dragged Constable off his wagon and humiliated him by making him kneel on the ground and swear his allegiance, and that these actions caused an eruption of violence in Mattoon the following day.[33] After the Republican victories in the Illinois elections of 1864, the legislature cut Constable's judicial circuit from six to two counties in early 1865.[31] In the diaries of his nephew Edmund C. Hinde, Constable is described as an honest man with good character, and his opponents are called "cowards" who did not understand the circumstances of the events.[3] According to historian David Williamson, Hinde's argument supporting his uncle's ruling has legal merit. He said that Chief Justice Roger B. Taney made a similar argument in Ex parte Merryman.[34]

Death

During the Civil War, Constable became addicted to morphine, which was then available for sale over the counter in pharmacies. In Edmund C. Hinde's diaries, Constable is described as a "slave" to morphine, and in one journal entry he is described as lying on the floor and talking like a child while on the drug. He died at the age of 48 from an overdose of morphine, while in Effingham, Illinois, in 1865, on circuit duty as a judge. His wife died shortly after he did. [3] One historian called it suicide.[32] Another source described it in the following way:

He departed this life some years ago, and the manner of that departure I shall not dwell upon. It was sad, but not dishonorable; and I do not believe that he left a single stain, blemish or blot upon his reputation; and I now bid farewell to his memory.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Perrin 1883, p. 291.

- ↑ Unsigned 1865.

- 1 2 3 4 Hinde 1850–1909.

- ↑ State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Library 1906, pp. 31–33

- ↑ Harper 1983

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Perrin 1883, p. 292.

- ↑ Lincoln 1809–1865, p. 48.

- ↑ Bateman 1918, p. 406.

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, pp. 20–31.

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, pp. 45–56.

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, pp. 74–86.

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, p. 45.

- 1 2 McKirdy 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ Lincoln 1809–1865.

- ↑ Stringer 1911, p. 282.

- ↑ Glenn 2011, p. 29.

- ↑ Hay 1991, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Burlingame 1997, p. 153-154.

- 1 2 McKirdy 2011, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Bateman 1918, p. 117.

- ↑ McKirdy 2011, p. 109.

- ↑ Towne 2006, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Klement 1989, p. 26.

- ↑ Towne 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Towne 2006, pp. 54.

- ↑ Towne 2006, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Towne 2006, pp. 43–62.

- ↑ Towne 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Coleman & Spence 1940, p. 26.

- 1 2 Towne 2006, p. 62.

- 1 2 Towne 2006, p. 63.

- ↑ Williamson 2011, p. 214.

- ↑ Williamson 2011, p. 104.

- ↑ Linder & Gillespie 1879, pp. 283–284.

References

- Barry, Peter, (2007), "Judge Carles H. Constable", The Charleston, Illinois Riot March 28, 1864, Published by author, 3 Lake Park, Champaign, Illinois

- Barry, Peter, (Spring 2008), "Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist and Copperhead" Journal of Illinois History, 11(1): 39-60.

- Bateman, Newton (1918). Historical encyclopedia of Illinois, Volume 1 (Google eBook). Munsell Pub. Co.,.

- Burlingame, Michael (1997). The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252066672.

- Coleman, Charles; Spence, Paul H. E. (March 1940). "The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Illinois State Historical Society. 33 (1): 7–56.

- Glenn, James R. (2011). The Fifth Judicial Circuit of Illinois(Google eBook). Trafford Publishing.

- Hay, Melba Porter (1991). The Papers of Henry Clay. Volume 10: Candidate, Compromiser, Elder Statesman, January 1, 1844 – June 29, 1852. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813100548.

- Harper, Josephine L. (1983). Guide to the Draper manuscripts. Madison : State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

- Hinde, Edmund C. (1850–1909). Personal Diaries at the California State Library. Edmund Hinde.

- Klement, Frank L. (1989). Dark Lanterns:Secret Political Societies, Conspiracies, and Treason Trials in the Civil War. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807115671.

- Lincoln, Abraham (1809–1865). Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln Volume 2. Abraham Lincoln. ISBN 978-1299115156.

- Linder, Usher F.; Gillespie, Joseph (1879). Reminiscences of the Early Bench and Bar of Illinois. The Chicago Legal News company. ISBN 978-1172195916.

- McKirdy, Charles R. (2011). Lincoln Apostate: The Matson Slave Case. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1604739855.

- Perrin, William Henry (1883). History of Crawford and Clark counties.

- State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Library (1906). Descriptive list of manuscript collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin:together with reports on other collections of manuscript material for American history in adjacent states (Google eBook). The Society.

- Stringer, Lawrence Beaumont (1911). History of Logan County, Illinois: A Record of Its Settlement, Organization, Progress, and Achievement (Google eBook). Unigraphic.

- Towne, Stephen E. (Spring 2006). "Such conduct must be put down: The Military Arrest of Judge Charles H. Constable during the Civil War.". Journal of Illinois History. 9 (2): 43–62.

- Unsigned (October 26, 1865). "Charles H. Constable Obituary". Daily Ohio Statesman.

- Williamson, David (2011). The 47th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786465958.

External links