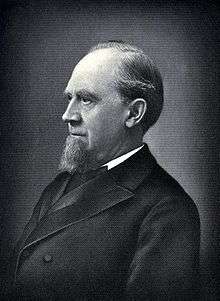

Charles Pratt

Charles Pratt (October 2, 1830 – May 4, 1891) was an American businessman and philanthropist.

Pratt was a pioneer of the U.S. petroleum industry, and established his kerosene refinery Astral Oil Works in Brooklyn, New York. He then lived with his growing family in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. An advertising slogan was "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil." He recruited Henry H. Rogers into his business, forming Charles Pratt and Company in 1867. Seven years later, Pratt and Rogers agreed to join John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil.

An advocate of education, Pratt founded and endowed the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, now a renowned art college. He and his children built country estates in Glen Cove, New York, developments in what became known as the Gold Coast in the 1920s on the North Shore of Long Island. In 1916, Standard Oil had a steamship tanker, first of its class, built at Newport News, Virginia and named it in honor of Pratt after his death.

Early life and education

Charles Pratt was born in Watertown, Massachusetts, one of eleven children. He was the son of Elizabeth Stone and Asa Pratt, a carpenter. He spent three winters as a student at Wesleyan Academy (now Wilbraham & Monson Academy).

Marriage and family

Pratt worked first in Boston, then moved to New York in 1850–1851. Soon after getting established there, in 1854 he married Lydia Ann Richardson (1835–1861). They had two children: Charles Millard Pratt (1855–1935) and Lydia Richardson Pratt (1857–1904) (who married Frank Lusk Babbott).

After his wife Lydia's early death in 1861, Pratt married her younger sister Mary Helen Richardson in September 1863. They had six children together:

- Frederic B. Pratt (1865–1945)

- Helen Pratt (1867–1949)

- George Dupont Pratt (1869–1935)

- Herbert L. Pratt (1871–1945)

- John Teele Pratt (1873–1927)

- Harold I. Pratt (1877–1939)

Career

Whale oil, petroleum, Astral Oil

As a young man, Pratt joined a company in nearby Boston, Massachusetts, that specialized in paints and whale oil products. In 1850 or 1851, he moved to New York City, where he worked for a similar company.

Pratt realized that whale oil could be replaced by petroleum ("natural oil") distillates to light lamps. He became a pioneer of the petroleum industry as new wells were established in western Pennsylvania in the 1860s. He soon established his kerosene refinery, Astral Oil Works, in Brooklyn, New York. One advertising slogan was "The holy lamps of Tibet are primed with Astral Oil."[1]

Henry H. Rogers, Charles Pratt and Company

In the mid-1860s, Pratt met two young men, Charles Ellis and Henry H. Rogers, in the area of the new oil fields of Venango County in western Pennsylvania. Previously, Pratt had bought whale oil from Ellis in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, his and Rogers' coastal hometown. They struck a deal and pre-sold the entire output of their small venture, Wamsutta Oil Refinery, to Pratt's company at a fixed price. But, Ellis and Rogers had no wells and were dependent upon purchasing crude oil to refine and sell to Pratt. A few months later, crude oil prices suddenly increased due to manipulation by speculators. The young entrepreneurs struggled to live up to their fixed-price contract with Pratt, but soon their surplus of funds was gone and they were heavily in debt to Pratt.

Ellis gave up, but in 1866, Rogers went to Pratt in New York City to say he would take personal responsibility for the entire debt. Impressed, Pratt immediately hired Rogers for his own organization. Pratt made Rogers foreman of his Brooklyn refinery, with a promise of a partnership if sales ran over $50,000 annually. Rogers moved with his young family to the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. He advanced from foreman to manager, and then was promoted to superintendent of Pratt's Astral Oil Refinery.

Pratt soon gave Rogers an interest in the business. In 1867, with Rogers as a partner, Pratt established the firm of Charles Pratt and Company. According to Elbert Hubbard, a journalist, in the next few years Rogers became Pratt's "hands and feet and eyes and ears."[2]

Standard Oil

In the early 1870s, Pratt and Rogers became involved in conflicts with John D. Rockefeller's South Improvement Company. Rockefeller had obtained favorable net rates from the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and other railroads through a secret system of rebates. His actions outraged independent oil producers and refineries in western Pennsylvania and other areas. The New York interests formed an association, and about the middle of March 1872, sent a committee of three, with Rogers as head, to Oil City, Pennsylvania to consult with the Oil Producers' Union.

Working with the Pennsylvania independents, Rogers and his associates forged an agreement with the PRR and other railroads; the railroads eventually agreed to open rates to all and promised to end their special dealings with South Improvement. The oil men felt victorious, but Rockefeller had already begun to buy up opposing interests in the formation of Standard Oil.

A short time later, Rockefeller approached Charles Pratt with plans for cooperation and consolidation. Pratt and Rogers decided that the plan would benefit their business plans. Rogers formulated terms which guaranteed financial security and jobs for Pratt and him, which Rockefeller accepted. Charles Pratt and Company (including Astral Oil) became one of the important former independent refiners to join Rockefeller's organization; it became part of the Standard Oil Trust in 1874. Pratt's eldest son, Charles Millard Pratt (1855–1935), became Secretary of Standard Oil, and in 1923 his son Herbert Lee Pratt rose to become head of Standard Oil of New York.

Although the merger made Pratt a wealthy man, as a member of the board of directors of Standard Oil, he maintained his independence and frequently criticized Rockefeller. With Pratt's death in 1891, Rockefeller's position as the most powerful man in the oil industry, already well established, became unassailable.

Legacy and honors

Charles Pratt is credited with recognizing the growing need for trained industrial workers in a changing economy. In 1886, he founded and endowed the Pratt Institute, which opened in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn in 1887. Originally a technical institute, it has become a renowned art, design and architectural college.

Long Island mansions

Pratt moved to a country home in Glen Cove, New York, about 1890. To provide for his children, he purchased large tracts of land surrounding his estate, totaling 1,100 acres (4.5 km²). He died the next year, aged 60, in New York City.

Charles Pratt's six sons and two daughters later built their own family estates in Glen Cove. As of 2004, most of the extant Pratt family Gold Coast Mansions are still in use:

- Welwyn, originally the home of Harold I. Pratt, is owned by and operated as the Welwyn Preserve, a Nassau County park. The mansion is now the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County.[3]

- The Braes, originally owned by Herbert L. Pratt, is now the Webb Institute of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering.

- The Manor House, built for John Teele Pratt, is now the Glen Cove Mansion Hotel & Conference Center.

- Poplar Hill, the Frederic B. Pratt house, is now the Glengariff Healthcare Center, housing both Glengariff, a long-term nursing care facility and the Pratt Pavilion for Nursing and Rehabilitation, a state-of-the-art, short-term, sub-acute rehabilitation center.

- Killenworth, originally the house of George Dupont Pratt, has, since the mid-20th century, been the country retreat for the Russian Delegation to the United Nations.

Pratt Cemetery

With so many Pratt family members in Glen Cove, they had a cemetery built for themselves on their property. Known as "Pratt Cemetery", behind ornate gates and up a winding drive stands a pink granite Romanesque mausoleum designed by William Tubby, as well as a crypt and a tower connected by a "bridge of sighs". Charles Pratt is interred in a sarcophagus here, as are seven out of his eight children, and many of his grandchildren.[4]

Other notable Pratt descendants

- Andy Pratt (born 1947 in Boston), a great-grandson whose father Edwin H Baker Pratt was headmaster of the school Buckingham Browne & Nichols, is a singer-songwriter[5]

- Sherman Pratt (1900–1964), founder of Marineland of Florida

Steamship tanker S.S. Charles Pratt

In March 1916, Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company launched the S.S. Charles Pratt, a tanker of 8,807 tons with a capacity of 119,410 barrels (18,985 m3) of oil. It became the first ship of the Pratt class, and was joined by the S.S. H.H. Rogers in May, 1916.

After 1939, both ships were operated by Panama Transport Co., a subsidiary of Standard Oil of New Jersey. At the beginning of World War II, on December 21, 1940, the S.S. Charles Pratt was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat in the Indian Ocean 220 miles (350 km) off the coast of Africa while en route from Aruba to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Of the American crew of 42, only two men died.

Pratt, West Virginia

The town of Pratt, West Virginia (previously known as Clinton) was renamed Pratt in 1905, after the owner of the Charles Pratt Coal Company.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Brooklyn Pratt Works 1939 WPA Guide to New York City

- ↑ Elbert Hubbard, Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great, Vol. 11, Great Businessmen, Roycoft, 1909, at Project Gutenberg, online books at University of Pennsylvania, accessed 25 February 2012

- ↑ "Welwyn Preserve County Park". nynjtc.org. New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ http://www.oldlongisland.com/2008/01/manor-house-home-of-john-teele-pratt-sr.html. Retrieved 5 May 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Andy Pratt.com Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://trimblehouse.wordpress.com/2011/04/19/a-brief-history-of-pratt-wv-1781-1913/. Retrieved 5 May 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Elbert Hubbard, 1909, Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great, Vol. 11, Great Businessmen, collected pieces originally published monthly in his magazine, volumes available at Project Gutenberg, at University of Pennsylvania

- Tarbell, Ida M. 1904, The History of Standard Oil

- "History of Glen Cove", Glen Cove, Long Island website

- "Pratt Institute", Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) website

- "History", Pratt Institute Official Website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Pratt. |