Chestnuts Long Barrow

View looking east through the burial chamber | |

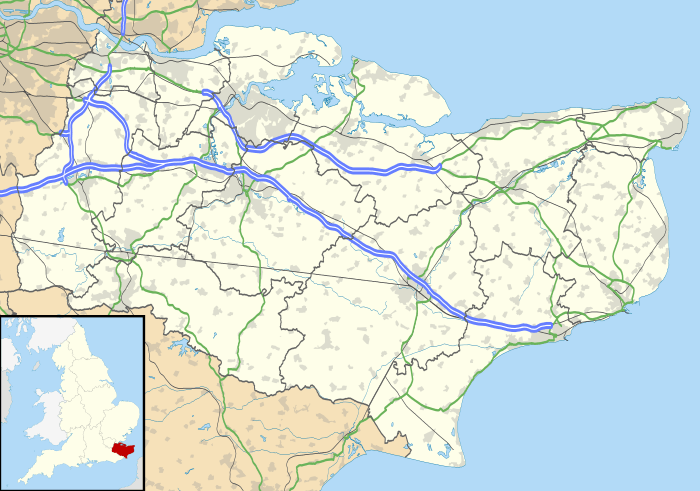

Location within Kent | |

| Location | Addington, Kent |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°18′28″N 0°22′10″E / 51.307655°N 0.369557°E |

| Type | Long barrow |

The Chestnuts Long Barrow, also known as Stony or Long Warren, is a chambered long barrow located near to the village of Addington in the southeastern English county of Kent. Constructed circa 4000 BCE, during the Early Neolithic period of British prehistory, today it survives only in a ruined state.

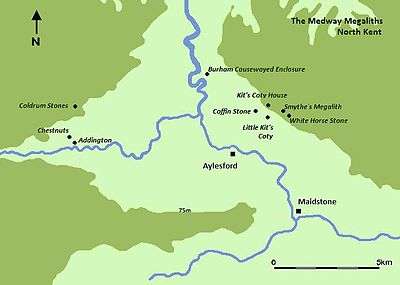

Archaeologists have established that the monument was built by pastoralist communities shortly after the introduction of agriculture to Britain from continental Europe. Although representing part of an architectural tradition of "barrow", or tumulus, building that was widespread across Neolithic Europe, the Chestnuts Long Barrow belong to a localised regional variant of barrows produced in the vicinity of the River Medway, now known as the Medway Megaliths. Of these, it lies near to both Addington Long Barrow and Coldrum Long Barrow on the western side of the river. Three further surviving long barrows, Kit's Coty House, the Little Kit's Coty House, and the Coffin Stone, are located on the Medway's eastern side.

The location selected for the barrow had witnessed inhabitation during the preceding Mesolithic period, as evidenced by a nearby hearth and scatters of knapped flint tools. Built out of earth and local sarsen megaliths, the long barrow consisted of a sub-rectangular earthen tumulus. Within the eastern end of the tumulus was a stone chamber, into which human remains were deposited, alongside sherds of pottery vessels. The barrow was still standing in the 4th century CE, when a small Romano-British hut was erected next to it. Around the 12th or 13th century, the chamber was systematically turned over, perhaps by treasure hunters or iconoclastic Christians. Pits were dug under the stones and the barrow was shovelled away. This caused the chamber to collapse, sealing medieval sherds under the stones. The ruin attracted the interest of antiquarians in the 18th and 19th centuries, while archaeological excavation took place in 1957, followed by limited reconstruction. The site is located on private land; visits can be organised by appointment with the land owner.

Name and location

The long barrow gained its name from the Chestnuts, an area of woodland that crowns the hill on the slopes of which the barrow is located.[1] Prior to the adoption of this name, the site was known locally as Stony or Long Warren.[1]

The site is located in the greensand belt, 100 feet above sea level.[2] The underlying geology is a soft sandstone covered with a stratum of white sand.[3] A Scheduled Ancient Monument,[2] the monument is situated on private land although visitors are permitted entry to it on payment of a small fee to the landowner, who resides in the neighbouring house, Rose Alba.[4]

Context

The Early Neolithic was a revolutionary period of British history. Between 4500 and 3800 BCE, it saw a widespread change in lifestyle as the communities living in the British Isles adopted agriculture as their primary form of subsistence, abandoning the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that had characterised the preceding Mesolithic period.[5] This came about through contact with continental societies, although it is unclear to what extent this can be attributed to an influx of migrants or to indigenous Mesolithic Britons adopting agricultural technologies from the continent.[6] The region of modern Kent would have been a key area for the arrival of continental European settlers and visitors, because of its position on the estuary of the River Thames and its proximity to the continent.[7] Britain was largely forested in this period,[8] with Kent only seeing widespread forest clearance in the Late Bronze Age.[9] Environmental data from the area around the White Horse Stone — a megalith in the vicinity of Chestnuts Long Barrow — supports the idea that the area was still largely forested in the Early Neolithic, covered by a woodland of oak, ash, hazel/alder and Maloideae.[10] Throughout most of Britain, there is little evidence of cereal or permanent dwellings from this period, leading archaeologists to believe that the Early Neolithic economy on the island was largely pastoral, relying on herding cattle, with people living a nomadic or semi-nomadic way of life.[11]

Medway Megaliths

Across Western Europe, the Early Neolithic marked the first period in which humans built monumental structures in the landscape.[12] These were tombs that held the physical remains of the dead, and though sometimes constructed out of timber, many were built using large stones, now known as "megaliths".[13] Individuals were rarely buried alone in the Early Neolithic, instead being interned in collective burials with other members of their community.[14] The construction of these collective burial monumental tombs, both wooden and megalithic, began in continental Europe before being adopted in Britain in the first half of the fourth millennium BCE.[15]

Although now all in a ruinous state and not retaining their original appearance,[16] at the time of construction the Medway Megaliths would have been some of the largest and most visually imposing Early Neolithic funerary monuments in Britain.[17] Grouped along the River Medway as it cuts through the North Downs,[18] they constitute the most southeasterly group of megalithic monuments in the British Isles,[19] and the only megalithic group in eastern England.[20] Archaeologists Brian Philp and Mike Dutto deemed the Medway Megaliths to be "some of the most interesting and well known" archaeological sites in Kent,[21] while archaeologist Paul Ashbee described them as "the most grandiose and impressive structures of their kind in southern England".[22]

They can be divided into two separate clusters: one to the west of the River Medway and the other on Blue Bell Hill to the east, with the distance between the two clusters measuring at between 8 and 10 km.[23] The western group includes Coldrum Long Barrow, Addington Long Barrow, and the Chestnuts Long Barrow.[24] The eastern group consists of Kit's Coty House, Little Kit's Coty House, the Coffin Stone, and several other stones which might have once been parts of chambered tombs.[25] It is not known if they were all built at the same time, or whether they were constructed in succession,[26] while similarly it is not known if they each served the same function or whether there was a hierarchy in their usage.[27]

The Medway long barrows all conformed to the same general design plan,[28] and are all aligned on an east to west axis.[28] Each had a stone chamber at the eastern end of the mound, and they each probably had a stone facade flanking the entrance.[28] The chambers were constructed from sarsen, a dense, hard, and durable stone that occurs naturally throughout Kent, having formed out of silicified sand from the Eocene. Early Neolithic builders would have selected blocks from the local area, and then transported them to the site of the monument to be erected.[29]

Such common architectural features among these tomb-shrines indicate a strong regional cohesion with no direct parallels elsewhere in the British Isles.[30] For instance, they would have been taller than most other tomb-shrines in Britain, with internal heights of up to 10 ft.[31] Nevertheless, as with other regional groupings of Early Neolithic tomb-shrines – like the Cotswold-Severn group – there are also various idiosyncrasies in the different monuments, such as Coldrum's rectilinear shape, the Chestnut long barrow's facade, and the long, thin mounds at Addington and Kit's Coty.[32] This variation might have been caused by the tomb-shrines being altered and adapted over the course of their use; in this scenario, the monumnets would represent composite structures.[33]

It seems apparent that the people who built these monuments were influenced by pre-existing tomb-shrines that they were already aware of.[34] Whether those people had grown up locally, or moved into the Medway area from elsewhere is not known.[34] Based on a stylistic analysis of their architectural designs, the archaeologist Stuart Piggott thought that they had originated in the area around the Low Countries,[35] while fellow archaeologist Glyn Daniel instead believed that the same evidence showed an influence from Scandinavia.[36] John H. Evans instead suggested an origin in Germany,[37] and Ronald F. Jessup thought that their origins could be seen in the Cotswold-Severn megalithic group.[38] Ashbee noted that their close clustering in the same area was reminiscent of the megalithic tomb-shrine traditions of continental Northern Europe,[22] and emphasised that the Medway Megaliths were a regional manifestation of a tradition widespread across Early Neolithic Europe.[39] He nevertheless stressed that a precise place of origin was "impossible to indicate" with the available evidence.[40]

Design and construction

Excavation revealed a Mesolithic layer below the monument, evidenced by much debris produced by flint knapping.[41] During the 1957 excavation of the site, 2300 Mesolithic flint fragments were found, while many more have been discovered in test trenches around the area, stretching up the hill towards Chestnuts Wood as well as for at least 200 yards east of the tomb and 400 yards south-west of it.[42] Around 100 feet west of the tomb, an excavation found flints in association with what was interpreted as evidence for a Mesolithic hearth.[43] The large quantities of Mesolithic material, coupled with its wide spread, indicated that the site was likely used as a place of inhabitation over a considerable length of time during the Mesolithic period.[43] Some of the trenches excavated in 1957 had Mesolithic flints directly below the megaliths, leading the excavator John Alexander to believe that "no great interval of time separated" the Mesolithic and Neolithic usages of the site.[44]

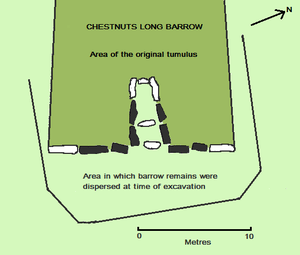

Chestnuts Long Barrow was constructed in particularly close proximity to Addington Long Barrow.[45] The sarsens used occur naturally within a few miles of the site.[46] The tomb was built from sarsen borders that were arranged as two trilithons,[47] and was oriented almost east to west.[48] As with four of the other Medway Megaliths, it appears to have been oriented toward either the Medway Valley or the North Downs.[49] The chamber was a trapezoid in its shape, measuring about 12 feet long and 7-and-a-half feet wide.[50] The chamber was likely 10 feet in height.[51] It is likely that the entrance to the chamber was almost entirely blocked by a large stone, designated 'G' by excavators.[52] Although it is difficult to determine the precise original layout of the chamber as a result of damage caused by medieval robbers,[53] it appears likely that a medial stone divided the chamber in two.[52] Furthermore, within the chamber, a drystone wall would have also blocked access.[52]

Alexander suggested that the barrow was constructed before the chamber, and that it was used as a ramp on which to drag the large stones into position.[54] He suggested that these megaliths were covered with sand until the capstones were placed atop the chamber, at which the sand was then cleared.[54] In 1950, it was stated that fourteen of the stones currently survive,[55] although following full excavation it was revealed that eighteen large sarsen boulders were extant, alongside four smaller sarsen stones used in the drystone wall and pavement of the tomb.[56]

The chamber had a pavement set in yellow sand, onto which human remains were then placed.[53] These human remains were evidenced by the discovery of 3,500 pieces of bone, reflecting a minimum of nine or ten individuals, at least one of whom was a child.[57] Some of these burials were inhumed, and others were cremated, while the earlier bones were deposited alongside Windmill Hill pottery.[46] Little evidence of inhumed burials was found, in part because they did not survive well in the acidic soils surrounding the site.[58] The appearance of cremated human bone here is unusual; although evidence of cremation has been found at some other long barrows, generally it is rare in Early Neolithic Britain.[59] Ashbee suggested that for this reason, the inclusion of cremated bone here must have had "especial significance".[60] While acknowledging that there was clear evidence of Early Neolithic cremation at certain sites in Britain, Smith and Brickley however suggested the possibility that the cremated bone was added at a later date, during the Late Neolithic, when cremation had become more common.[61] Along with these human remains were found other items likely interned with the dead, such as 34 sherds of ceramic, three stone arrow heads, and a clay pendant.[62] In the foreground of the site, excavators found 100 sherds of Windmill Hill ware, representing parts of at least eight bowls, which it was suggested had once been found in the chamber but which had been removed in order to allow the deposition of further human remains inside of it.[53]

Although no visible tumulus survived into the 1950s, the name "Long Warren" suggested that knowledge of such a mound had been known at least into the eighteenth century.[63] Excavation found evidence of the northern and eastern edges of the barrow,[64] however all trace of the western and southern ends of the barrow had been destroyed by levelling and deep ploughing.[54] From the excavation, archaeologists expressed the view that the barrow was likely trapezoidal or D-shaped, with a width of about 60 feet.[54] It was more difficult to determine the length, although the archaeologist studying the site suggested that it may have been about 50 feet long.[65]

Meaning and purpose

The Early Neolithic people of Britain placed far greater emphasis on the ritualised burial of the dead than their Mesolithic forebears had done.[14] Many archaeologists have suggested that this is because Early Neolithic people adhered to an ancestor cult that venerated the spirits of the dead, believing that they could intercede with the forces of nature for the benefit of their living descendants.[66] Archaeologist Robin Holgate stressed that rather than simply being tombs, the Medway Megaliths were "communal mouments fulfilling a social function for the communities who built and used them."[26] Thus, it has furthermore been suggested that Early Neolithic people entered into the tombs – which doubled as temples or shrines – to perform rituals that would honour the dead and ask for their assistance.[67] For this reason, historian Ronald Hutton termed these monuments "tomb-shrines" to reflect their dual purpose.[68]

In Britain, these tombs were typically located on prominent hills and slopes overlooking the surrounding landscape, perhaps at the junction between different territories.[69] Archaeologist Caroline Malone noted that the tombs would have served as one of a variety of markers in the landscape that conveyed information on "territory, political allegiance, ownership, and ancestors."[70] Many archaeologists have subscribed to the idea that these tomb-shrines served as territorial markers between different tribal groups, although others have argued that such markers would be of little use to a nomadic herding society.[71] Instead it has been suggested that they represent markers along herding pathways.[72] Many archaeologists have suggested that the construction of such monuments reflects an attempt to stamp control and ownership over the land, thus representing a change in mindset brought about by Neolithicisation.[73] Others have suggested that these monuments were built on sites already deemed sacred by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.[74]

Subsequent history

During excavation of the site, four ceramic sherds were found in the vicinity which the excavator believed were possibly Early Iron Age in origin.[75] Excavation also revealed 830 ceramic sherds dating from Roman Britain; although most of these were dated to the fourth century, the sherds reflected all four centuries of this period. Dated to the fourth century was a hut that had been erected on a flat area adjacent to the barrow.[76] Evidence of human activity at this hut was found in the form of 750 ceramic sherds, charcoal, iron nails, burnt clay, bone, and flint fragments.[77] Examining this assemblage of artefacts, the excavator noted that it was not typical of the item assemblages usually found at Romano-British settlement sites, thus suggesting that the building was a field shelter rather than a house.[78]

Evidence for human activity in the vicinity of the barrow from the eleventh through to the thirteenth century – during the medieval period – appeared in the form of 200 ceramic sherds, 2 hones, and 17 fragments of daub found by archaeologists in the top soil.[79] It was likely in this medieval period that the tomb was heavily destroyed, evidenced by medieval material found in some of the pits created by those damaging the chamber and barrow.[80] The destruction was carried out in a systematic manner.[81] Initially, the barrow around the chamber was dug away, and an entrance into it was forced through the drystone wall at the north-western end. The chamber was then cleared down to the bedrock, with the spoil and contents of the chamber dumped behind the diggers. The medial stone of the chamber was pushed over on to the spoil heap, and covered over with soil. A pit was dug in the centre of the chamber, and against its walls from the outside; the central pit was then ceiled by the collapsing capstones. Finally, several more pits were then dug around the façade stones.[81] Subsequently, the chamber collapsed, with a number of stones breaking on the impact of the fall.[82] At some point after they had fallen, the inner pair of the chamber's tall-stones were further damaged, likely in a process involving heating them with fire and then casting cold water onto them, resulting in breakage.[83]

From the available evidence, it was clear that this demolition was not carried out with the intent of collecting building stone nor for the clearance of ground for cultivation.[84] Ashbee thought iconoclasm was likely, believing that the burial of the stones likely indicated that Christian zealots were trying to deliberately destroy and defame the pre-Christian monument.[85] Conversely, Alexander believed that there was no evidence of iconoclasm, and instead believed that this damage resulted from a robbery.[86] Supporting this idea is comparative evidence, with the Close Roll of 1237 ordering the opening of barrows on the Isle of Wight in search for treasure, a practice which may have spread to Kent around the same time.[87] Alexander believed that the destruction may have been brought about by a special commissioner, highlighting that the "expertness and thoroughness of the robbery" would have necessitated resources beyond that which a local community could likely produce.[87] He further suggested that the individuals responsible for damaging the monument might also have been those responsible for doing the same at Kit's Coty House, Coldrum long barrow, and Addington long barrow,[87] while Ashbee suggested that the same could also be the case for Lower Kit's Coty House.[88]

Archaeological excavation also revealed evidence for modern activity around the site. Three post-medieval pits were identified in and around the barrow, as well as a post-medieval attempt to dig into the chamber.[82] Finds from this period included ceramic sherds, clay pipes dated from between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, stone and clay marbles, brick tile, and bottles dated from between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries.[82] Alexander suggested that this evidence confirmed local accounts that it had been used as a popular spot for picnics.[82] There are also accounts that it came to be used as a well-known rabbit warren in the local area.[82]

Folklore and folk tradition

In a 1946 paper published in the Folklore journal, John H. Evans recorded that there was a folk belief in the area that applied to all of the Medway Megaliths and which had been widespread "up to the last generation"; this was that it was impossible for any human being to successfully count the number of stones in the monuments.[89] This "countless stones" motif is not unique to this particular site, and can be found at various other megalithic monuments in Britain. The earliest textual evidence for it is found in an early sixteenth-century document, where it applies to the stone circle of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, although in an early seventeenth-century document it was being applied to The Hurlers, a set of three stone circles in Cornwall.[90] Later records reveal that it had gained widespread distribution in England, as well as a single occurrence each in Wales and Ireland.[91] The folklorist S.P. Menefee suggested that it could be attributed to an animistic understanding that these megaliths had lives of their own.[92]

Antiquarian and archaeological investigation

The existence of Chestnuts Long Barrow has been known since the 18th century.[2] The earliest possible reference to the monuments was provided by the antiquarian John Harris in an ambiguous comment included in his History of Kent in Five Parts, published in 1719.[93] In 1773, the site was described in print by the antiquarian Josiah Colebrooke in a short article that he wrote for Archaeologia, the journal of the Society of Antiquaries of London, in 1773.[94] He described it as one of the "temples of the antient [sic] Britons".[95] Colebrook's analysis was echoed in the 18th-century writings of Edward Hasted, W. H. Ireland, and John Thorpe.[96] In the early 1840s, the Reverend Beale Post conducted investigations into the Medway Megaliths, writing them up in a manuscript that was left unpublished; this included Addington Long Barrow and Chestnuts Long Barrow, which he collectively labelled the "Addington Circles".[97]

During the late 19th century, the field in which the barrow is located was used as a paddock.[2] In the late 1940s, the site was visited by the archaeologist John H. Evans and his Dutch counterpart Albert Egges van Giffen, with the former commenting that they examined the site in its "overgrown state".[55] In 1953, the archaeologist Leslie Grinsell reported that several small trees and bushes had grown up within the megaliths at the site.[98] That same year, the field was prepared for horticultural usage, being levelled and deeply ploughed, although the area around the megaliths was left undisturbed.[99] At this time, sixteen megaliths were visible, and were laying at a variety of angles, with a fifty foot high holly tree growing in the centre of them; there was no sign of a tumulus.[99] The landowner, Richard Boyle, opened a few test trenches in the area, during which he discovered Mesolithic flint tools, while a large number of surface finds were also found in both the field and a quarry located 100 feet to the east.[3]

In the latter part of the 1950s, with plans afoot to construct a house adjacent to the monument, the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments brought about the excavation of the site.[100] Over the course of five weeks in August and September 1957, the barrow was excavated under the directorship of John Alexander.[101] The excavation was initiated and funded by Boyle, with the support of the Inspectorate, and was largely carried out by volunteer excavators.[2] Following excavation, the fallen sarsen megaliths were re-erected in their original sockets, allowing for the restoration of part of the chamber and façade.[102] The finds recovered from the excavation were placed in Maidstone Museum.[4] Alexander subsequently wrote what has been described as a "comprehensive excavation report" which was "a model of its kind".[100]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, p. 1; Ashbee 2000, p. 325.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexander 1961, p. 1.

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, p. 2.

- 1 2 Philp & Dutto 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Hutton 1991, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Hutton 1991, p. 16; Ashbee 1999, p. 272; Hutton 2013, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Holgate 1981, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Barclay et al. 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Barclay et al. 2006, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Champion 2007, pp. 73–74; Hutton 2013, p. 33.

- ↑ Hutton 1991, p. 19; Hutton 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Hutton 1991, p. 19.

- 1 2 Malone 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Malone 2001, pp. 103–104; Hutton 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Holgate 1981, p. 225; Champion 2007, p. 78.

- ↑ Champion 2007, p. 76.

- ↑ Wysocki et al. 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Garwood 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Holgate 1981, p. 221.

- ↑ Philp & Dutto 2005, p. 1.

- 1 2 Ashbee 1999, p. 269.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, pp. 60–61; Champion 2007, p. 78; Wysocki et al. 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Ashbee 2005, p. 101; Champion 2007, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Ashbee 2005, p. 101; Champion 2007, p. 78.

- 1 2 Holgate 1981, p. 223.

- ↑ Holgate 1981, pp. 223, 225.

- 1 2 3 Champion 2007, p. 78.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 58; Champion 2007, p. 78.

- ↑ Holgate 1981, p. 225; Wysocki et al. 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Killick 2010, p. 339.

- ↑ Wysocki et al. 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 60.

- 1 2 Holgate 1981, p. 227.

- ↑ Piggott 1935, p. 122.

- ↑ Daniel 1950, p. 161.

- ↑ Evans 1950.

- ↑ Jessup 1970, p. 111.

- ↑ Ashbee 1999, p. 271.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 57.

- ↑ Alexander 1958, p. 191; Alexander 1961, p. 2.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, p. 3.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 5.

- ↑ Killick 2010, p. 342.

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, p. 13.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 6.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 6; Killick 2010, p. 342.

- ↑ Killick 2010, p. 346.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 8; Ashbee 1993, p. 61.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 9; Ashbee 1993, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Alexander 1961, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Alexander 1961, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Alexander 1961, p. 11.

- 1 2 Evans 1950, p. 75.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 55.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 9, 52–53.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 53.

- ↑ Smith & Brickley 2009, p. 57.

- ↑ Ashbee 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Smith & Brickley 2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 9, 49.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 10; Ashbee 2000, p. 325.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 10.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 11; Ashbee 2000, p. 325; Ashbee 1993, p. 60.

- ↑ Burl 1981, p. 61; Malone 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Burl 1981, p. 61.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Malone 2001, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Malone 2001, p. 107.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 40.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 22, 42.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 23, 43.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 23.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 24–25, 45.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, pp. 25, 45.

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexander 1961, p. 27.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 67.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 63.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Alexander 1961, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Alexander 1961, p. 25.

- ↑ Ashbee 2005, p. 104.

- ↑ Evans 1946, p. 38.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 146.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 147.

- ↑ Menefee 1975, p. 148.

- ↑ Harris 1719, p. 23; Ashbee 1993, p. 93.

- ↑ Colebrooke 1773, p. 23; Evans 1950, p. 75.

- ↑ Colebrooke 1773, p. 23; Ashbee 1993, p. 93.

- ↑ Ashbee 1993, p. 93.

- ↑ Evans 1949, p. 136.

- ↑ Grinsell 1953, p. 194.

- 1 2 Alexander 1961, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Ashbee 1993, p. 95.

- ↑ Alexander 1958, p. 191; Alexander 1961, p. 1; Philp & Dutto 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Ashbee 2000, p. 337.

Bibliography

- Alexander, John (1958). "Addington: The Chestnuts Megalithic Tomb" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 72: 191–192.

- ⸻ (1961). "The Excavation of the Chestnuts Megalithic Tomb at Addington, Kent" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 76: 1–57.

- Ashbee, Paul (1993). "The Medway Megaliths in Perspective" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 111: 57–112.

- ⸻ (1999). "The Medway Megaliths in a European Context" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 119: 269–284.

- ⸻ (2000). "The Medway's Megalithic Long Barrows" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 120: 319–345.

- ⸻ (2005). Kent in Prehistoric Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3136-9.

- Barclay, Alistair; Fitzpatrick, Andrew P.; Hayden, Chris; Stafford, Elizabeth (2006). The Prehistoric Landscape at White Horse Stone, Aylesford, Kent (Report). Oxford: Oxford Wessex Archaeology Joint Venture (London and Continental Railways).

- Burl, Aubrey (1981). Rites of the Gods. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-460-04313-7.

- Champion, Timothy (2007). "Prehistoric Kent". In John H. Williams. The Archaeology of Kent to AD 800. Woodbridge: Boydell Press and Kent County Council. pp. 67–133. ISBN 978-0-85115-580-7.

- Colebrooke, Josiah (1773). "An Account of the Monument Commonly Ascribed to Catigern" (PDF). Archaeologia. Society of Antiquaries of London. 2: 107–117.

- Daniel, Glynn E. (1950). The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, John H. (1946). "Notes on the Folklore and Legends Associated with the Kentish Megaliths". Folklore. The Folklore Society. 57 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1946.9717805. JSTOR 1257001.

- ⸻ (1949). "A Disciple of the Druids; the Beale Post Mss" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 62: 130–139.

- ⸻ (1950). "Kentish Megalith Types" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 63: 63–81.

- Grinsell, Leslie V. (1953). The Ancient Burial-Mounds of England (second ed.). London: Methuen & Co.

- Harris, John (1719). The History of Kent. London: D. Midwinter.

- Jessup, Ronald F. (1970). South-East England. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Killick, Sian (2010). "Neolithic Landscape and Experience: The Medway Megaliths" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. 130. Kent Archaeological Society. pp. 339–349.

- Garwood, P. (2012). "The Medway Valley Prehistoric Landscapes Project" (PDF). PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society. The Prehistoric Society. 72: 1–3.

- Holgate, Robin (1981). "The Medway Megaliths and Neolithic Kent" (PDF). Archaeologia Cantiana. Kent Archaeological Society. 97: 221–234.

- Hutton, Ronald (1991). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-17288-8.

- ⸻ (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Malone, Caroline (2001). Neolithic Britain and Ireland. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1442-9.

- Menefee, S.P. (1975). "The 'Countless Stones': A Final Reckoning". Folklore. The Folklore Society. 86 (3-4): 146–166. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1975.9716017. JSTOR 1260230.

- Philp, Brian; Dutto, Mike (2005). The Medway Megaliths (third ed.). Kent: Kent Archaeological Trust.

- Piggott, Stuart (1935). "A Note on the Relative Chronology of the English Long Barrows". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. The Prehistoric Society. 1: 115–126. doi:10.1017/s0079497x00022246.

- Smith, Martin; Brickley, Megan (2009). People of the Long Barrows: Life, Death and Burial in the Early Neolithic. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4733-9.

- Wysocki, Michael; Griffiths, Seren; Hedges, Robert; Bayliss, Alex; Higham, Tom; Fernandez-Jalvo, Yolanda; Whittle, Alasdair (2013). "Dates, Diet and Dismemberment: Evidence from the Coldrum Megalithic Monument, Kent". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Prehistoric Society. 79: 1–30. doi:10.1017/ppr.2013.10.