Climate of North Carolina

North Carolina's climate varies from the Atlantic coast in the east to the Appalachian Mountain range in the west. The mountains often act as a "shield", blocking low temperatures and storms from the Midwest from entering the Piedmont of North Carolina.[1] Most of the state has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), except in the higher elevations of the Appalachians which have a subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cfb). For most areas in the state, the temperatures in July during the daytime are approximately 90 °F (32 °C). In January the average temperatures range near 50 °F (10 °C). (However, a polar vortex or "cold blast" can significantly bring down average temperatures, seen in the winters of 2014 and 2015.)[2] In the month of August it rains an average of 4.21 inches.

Precipitation

There is an average of forty-five inches of rain a year (fifty in the mountains). July storms account for much of this precipitation. As much as 15% of the rainfall during the warm season in the Carolinas can be attributed to tropical cyclones.[3] Mountains usually see some snow in the fall and winter.[1] Moist winds from the southwest drop an average of 80 inches (2,000 mm) of precipitation on the western side of the mountains, while the northeast-facing slopes average less than half that amount.[4]

Snow

Snow in North Carolina is seen on a regular basis in the mountains. North Carolina averages 5 inches (130 mm) of snow a year. However, this also varies greatly across the state. Along the coast, most areas register less than 2 inches (51 mm) per year while the state capital, Raleigh averages 7.5 inches (190 mm). Farther west in the Piedmont-Triad, the average grows to approximately 9 inches (230 mm). The Charlotte area averages approximately 6.5 inches (170 mm). The mountains in the west act as a barrier, preventing most snowstorms from entering the Piedmont. When snow does make it past the mountains, it is usually light and is seldom on the ground for more than two or three days. However, several storms have dropped 18 inches (460 mm) or more of snow within normally warm areas. The 1993 Storm of the Century that lasted from March 11 to March 15 affected locales from Canada to Central America, and brought a significant amount of snow to North Carolina. Newfound Gap received more than 36 inches (0.91 m) of snow with drifts more than 5 feet (1.5 m), while Mount Mitchell measured over 4 feet (1.2 m) of snow with drifts to 14 feet (4.3 m).[5] Most of the northwestern part of the state received somewhere between 2 feet (0.61 m) an 3 feet (0.91 m) of snow.

Another significant snowfall hit the Raleigh area in January 2000, when more than 20 inches (510 mm) of snow fell.[6] There was also a heavy snowfall totaling 18 inches (460 mm) that hit the Wilmington area just before Christmas in 1989, with little snow measured west of I-95. Most of the major snows that impact areas east of the mountains come from extratropical cyclones which approach from the south across Georgia and South Carolina and move offshore the Carolinas. If the storms track too far east, the snow will be limited to the eastern part of the state. If the cyclones travel close to the coast, warm air will get drawn into eastern North Carolina due to increasing flow off the milder Atlantic Ocean, bringing a rain/snow line well inland with heavy snow restricted to the piedmont. If the storm tracks inland into eastern North Carolina, the rain/snow line ranges between Raleigh and Greensboro.[7]

Tropical cyclones

Located along the Atlantic Coast, North Carolina is no stranger to hurricanes. Many hurricanes that come up from the Caribbean Sea make it up the coast of eastern America, passing by North Carolina.

On October 15, 1954, Hurricane Hazel struck North Carolina, at that time it was a category 4 hurricane within the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. Hazel caused significant damage due to its strong winds. A weather station at Oak Island reported maximum sustained winds of 140 miles per hour (230 km/h), while in Raleigh winds of 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) were measured. The hurricane caused 19 deaths and significant destruction. One person at Long Beach claimed that "of the 357 buildings that existed in the town, 352 were totally destroyed and the other five damaged". Hazel was described as "the most destructive storm in the history of North Carolina" in a 1989 report.[8]

In 1996, Hurricane Fran made landfall in North Carolina. As a category 3 hurricane, Fran caused a great deal of damage, mainly through winds. Fran's maximum sustained wind speeds were 115 miles per hour (185 km/h), while North Carolina's coast saw surges of 8 feet (2.4 m) to 12 feet (3.7 m) above sea level. The amount of damage caused by Fran ranged from $1.275 to $2 billion in North Carolina.[8]

Rain

Heavy rains accompany tropical cyclones and their remnants which move northeast from the Gulf of Mexico coastline, as well as inland from the western subtropical Atlantic ocean. Over the past 30 years, the wettest tropical cyclone to strike the coastal plain was Hurricane Floyd of September 1999, which dropped over 24 inches (610 mm) of rainfall north of Southport. Unlike Hazel and Fran, the main force of destruction was from precipitation. Before Hurricane Floyd reached North Carolina, the state had already received large amounts of rain from Hurricane Dennis less than two weeks before Floyd. This saturated much of the Eastern North Carolina soil and allowed heavy rains from Hurricane Floyd to turn into floods. Over 35 people died from Floyd.[8] In the mountains, Hurricane Frances of September 2004 was nearly as wet, bringing over 23 inches (580 mm) of rainfall to Mount Mitchell.[9]

Severe weather

In most years, the greatest weather-related economic loss incurred in North Carolina is due to severe weather spawned by summer thunderstorms. These storms affect limited areas, with their hail and wind accounting for an average annual loss of over US$5 million.[10]

North Carolina averages 31 tornadoes a year with May seeing the most tornadoes on average a month with 5. June, July and August all have an average of 3 tornadoes with an increase to 4 average tornadoes a month in September. It is through September and into early November when North Carolina can typically expect to see that smaller, secondary, severe weather season. While severe weather season is technically from March through May, tornadoes have touched down in North Carolina in every month of the year.

Seasonal conditions

Winter

In winter, North Carolina is protected by the Appalachian Mountains on the western front. Cold fronts from Canada and the Gulf of Mexico rarely make it past the towering mountains. Cold winds make it across the peaks once or twice a year and force the temperatures to drop to about 10 °F (−12 °C) in central North Carolina. Although temperatures below zero degrees Fahrenheit are extremely rare outside of the mountains. The coldest ever recorded temperature in North Carolina was −34 °F (−37 °C) on January 21, 1985, at Mount Mitchell. The winter temperatures on the coast are mostly due to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream.[11] The average ocean temperature in Southport in January is still higher than the average ocean temperature in Maine during July.[11] Snow is common in the mountains, although many ski resorts use snowmaking equipment to make sure there is always snow on their land.[11] North Carolina's relative humidity is highest in the winter.[11]

Spring

Tornadoes are most likely early in the spring. The month of May experiences the greatest rise in temperatures. During the spring, there are warm days and cool nights in the piedmont. Temperatures are somewhat cooler in the mountains and warmer, particularly at night, near the coast.[11] North Carolina's humidity is lowest in the Spring.[11]

Summer

North Carolina experiences high summer temperatures. Sometimes, cool, dry air from the north will invade North Carolina for brief periods of time, with temperatures quickly rebounding.[12] It remains colder at high elevations, with the average summer temperature in Mount Mitchell lying at 68 °F (20 °C). Morning temperatures are on average 20 °F (12 °C) lower than afternoon temperatures, except along the Atlantic Coast.[11] The largest economic loss from severe weather in North Carolina is due to severe thunderstorms in the summer, although they usually only hit small areas.[11] Tropical cyclones can impact the state during the summer as well. Fogs are also frequent in the summer.

Fall

Fall is the most rapidly changing season temperature wise, especially in October and November.[11] Tropical cyclones remain a threat until late in the season. The Appalachian Mountains are frequently visited at this time of year, due to the leaves changing color in the trees.[11]

Southern Oscillation

During El Niño events, winter and early spring temperatures are cooler than average with above average precipitation in the central and eastern parts of the state and drier weather in the western part. La Niña usually brings warmer than average temperatures with above average precipitation in the western part of the state while the central and coastal regions stay drier than average.

Changes

The water on North Carolina's shores have risen 2 inches (50 mm).[13] Temperatures in North Carolina have risen too. Over the last 100 years, the average temperature in Chapel Hill has gone up 1.2 °F (0.7 °C) and precipitation in some parts of the state has increased by 5 percent.[14]

Statistics for selected cities

| Climate data for Asheville Regional Airport, North Carolina (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1869–present)[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

81 (27) |

100 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.2 (19) |

69.0 (20.6) |

76.4 (24.7) |

82.5 (28.1) |

85.5 (29.7) |

89.2 (31.8) |

91.3 (32.9) |

90.6 (32.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

80.7 (27.1) |

73.6 (23.1) |

66.3 (19.1) |

92.4 (33.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.4 (8.6) |

51.0 (10.6) |

58.7 (14.8) |

67.7 (19.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

81.3 (27.4) |

84.0 (28.9) |

82.9 (28.3) |

76.9 (24.9) |

68.1 (20.1) |

58.8 (14.9) |

49.5 (9.7) |

66.8 (19.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 26.7 (−2.9) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

35.5 (1.9) |

42.8 (6) |

51.4 (10.8) |

59.6 (15.3) |

63.7 (17.6) |

62.9 (17.2) |

55.8 (13.2) |

44.6 (7) |

35.8 (2.1) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

44.8 (7.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 8.4 (−13.1) |

13.5 (−10.3) |

19.9 (−6.7) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

36.0 (2.2) |

48.1 (8.9) |

55.0 (12.8) |

53.3 (11.8) |

41.3 (5.2) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

4.8 (−15.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−9 (−23) |

2 (−17) |

20 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

44 (7) |

42 (6) |

30 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

1 (−17) |

−7 (−22) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.67 (93.2) |

3.76 (95.5) |

3.83 (97.3) |

3.33 (84.6) |

3.66 (93) |

4.65 (118.1) |

4.31 (109.5) |

4.40 (111.8) |

3.81 (96.8) |

2.91 (73.9) |

3.65 (92.7) |

3.59 (91.2) |

45.57 (1,157.5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.1 (10.4) |

2.2 (5.6) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.9 (2.3) |

9.9 (25.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.0 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 128.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 5.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.6 | 69.8 | 68.4 | 66.2 | 75.3 | 78.6 | 81.6 | 83.5 | 84.1 | 78.4 | 74.8 | 74.1 | 75.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 175.9 | 181.2 | 223.5 | 252.3 | 264.1 | 267.0 | 257.5 | 227.8 | 207.5 | 219.6 | 178.8 | 167.2 | 2,622.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 59 | 60 | 64 | 61 | 61 | 58 | 55 | 56 | 63 | 58 | 55 | 59 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1964–1990, sun 1961–1990)[15][16][17] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

- North – includes the neighborhoods of Albemarle Park, Beaverdam, Beaver Lake, Chestnut Hills, Colonial Heights, Five Points, Grove Park, Hillcrest, Kimberly, Klondyke, Montford, and Norwood Park. Chestnut Hill, Grove Park, Montford, and Norwood Park neighborhoods are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Montford and Albemarle Park have been named local historic districts by the Asheville City Council.

- East – includes the neighborhoods of Kenilworth, Beverly Hills, Chunn's Cove, Haw Creek, Oakley, Oteen, Reynolds, Riceville, and Town Mountain.

- West – includes the neighborhoods of Camelot, Wilshire Park, Bear Creek, Deaverview Park, Emma, Hi-Alta Park, Lucerne Park, Malvern Hills, Sulphur Springs, Haywood Road, and Pisgah View.

- South – includes the neighborhoods of Ballantree, Biltmore Village, Biltmore Park, Oak Forest, Royal Pines, Shiloh, and Skyland. Biltmore Village has been named a local historic district by the Asheville City Council.[18]

Architecture

Notable architecture in Asheville includes its Art Deco city hall, and other unique buildings in the downtown area, such as the Battery Park Hotel, the original of which was 475-feet long with numerous dormers and chimneys; the Neo-Gothic Jackson Building, the first skyscraper on Pack Square; Grove Arcade, one of America's first indoor shopping malls;[19] and the Basilica of St. Lawrence. The S&W Cafeteria Building is also a fine example of Art Deco architecture in Asheville.[20] The Grove Park Inn is an important example of architecture and design of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Asheville's recovery from the Depression was slow and arduous. Because of the financial stagnation, there was little new construction and much of the downtown district remained unaltered. This however has allowed Asheville to be a great collection of Art Deco and truly a style all its own.

The Montford Area Historic District and other central areas are considered historic districts and include Victorian houses. On the other hand, Biltmore Village, located at the entrance to the famous estate, showcases unique architectural features that are found only in the Asheville area. It was here that workers stayed during the construction of George Vanderbilt's estate. Today, however, as with many of Asheville's historical districts, it has been transformed into a district home to quaint, trendy shops and interesting boutiques. The YMI Cultural Center, founded in 1892 by George Vanderbilt in the heart of downtown, is one of the nation's oldest African-American cultural centers.[21][22]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 38 | — | |

| 1860 | 502 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,400 | 178.9% | |

| 1880 | 2,616 | 86.9% | |

| 1890 | 10,235 | 291.2% | |

| 1900 | 14,694 | 43.6% | |

| 1910 | 18,762 | 27.7% | |

| 1920 | 28,504 | 51.9% | |

| 1930 | 50,193 | 76.1% | |

| 1940 | 51,310 | 2.2% | |

| 1950 | 53,000 | 3.3% | |

| 1960 | 60,192 | 13.6% | |

| 1970 | 57,929 | −3.8% | |

| 1980 | 54,022 | −6.7% | |

| 1990 | 61,607 | 14.0% | |

| 2000 | 68,889 | 11.8% | |

| 2010 | 83,393 | 21.1% | |

| Est. 2015 | 88,512 | [23] | 6.1% |

| 2011 estimate | |||

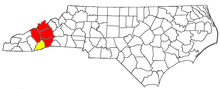

Asheville is the larger principal city of the Asheville-Brevard CSA, a Combined Statistical Area that includes the Asheville metropolitan area (Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson, and Madison counties) and the Brevard micropolitan area (Transylvania County),[24][25][26] which had a combined population of 398,505 at the 2000 census.[27]

At the 2000 census,[28] there were 68,889 people, 30,690 households and 16,726 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,683.4 per square mile (650.0/km²). There were 33,567 housing units at an average density of 820.3 per square mile (316.7/km²). The racial composition of the city was: 77.95% White, 17.61% Black or African American, 3.76% Hispanic or Latino American, 0.92% Asian American, 0.35% Native American, 0.06% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 1.53% some other race, and 1.58% two or more races.

There were 30,690 households of which 22.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.1% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.5% were non-families. 36.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.81.

Age distribution was 19.6% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 28.7% from 25 to 44, 23.1% from 45 to 64, and 18.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.9 males.

The median household income was $32,772, and the median family income was $44,029. Males had a median income of $30,463 versus $23,488 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,024. About 13% of families and 19% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.9% of those under age 18 and 10.1% of those age 65 or over.

Religion

Asheville is the headquarters of the Episcopal Diocese of Western North Carolina, which is seated at the Cathedral of All Souls. Asheville is also an important city for North Carolinian Catholics, who make pilgrimages to the Basilica of St. Lawrence.

Metropolitan area

Asheville is the largest city located within the Asheville MSA (Metropolitan Statistical Area). The MSA includes Buncombe County; Haywood County; Henderson County; and Madison County; with a combined population – as of the 2014 Census Bureau population estimate – of 442,316.[29]

Apart from Asheville, the MSA includes Hendersonville and Waynesville, along with a number of smaller incorporated towns: Biltmore Forest, Black Mountain, Canton, Clyde, Flat Rock, Fletcher, Hot Springs, Laurel Park, Maggie Valley, Mars Hill, Marshall, Mills River, Montreat, Weaverville and Woodfin.

Several sizable unincorporated rural and suburban communities are also located nearby: Arden, Barnardsville (incorporated until 1970), Bent Creek, Candler, Enka, Fairview, Jupiter (incorporated until 1970), Leicester, Oteen, Skyland, and Swannanoa.

Economy

Largest employers

According to the city's 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[30] the largest employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mission Health System | 3,000+ |

| 2 | Buncombe County Schools System | 3,000+ |

| 3 | Ingles Markets, Inc. | 3,000+ |

| 4 | State of North Carolina | 1,000+ |

| 5 | Buncombe County | 1,000+ |

| 6 | Asheville VA Medical Center | 1,000+ |

| 7 | City of Asheville | 1,000+ |

| 8 | Wal-Mart | 1,000+ |

| 9 | The Biltmore Company | 1,000+ |

| 10 | Asheville–Buncombe Technical Community College | 1,000+ |

| 11 | Eaton | 1,000+ |

| 12 | Grove Park Inn | 500–999 |

| 13 | Asheville City Schools | 500–999 |

| 14 | Community CarePartners | 500–999 |

| 15 | United States Postal Service | 500–999 |

| 16 | BorgWarner Turbo Systems | 500–999 |

| 17 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 500–999 |

| 18 | Arvato Digital Services | 500–999 |

| 19 | Employment Control | 500–999 |

| 20 | Volvo Construction Equipment | 500–999 |

Politics

Local government

The City of Asheville operates under a council-manager form of government, via its charter. The city council appoints a city manager, a city attorney, and a city clerk.[31] In the absence or disability of the mayor, the vice-mayor performs the mayoral duties. The vice-mayor is appointed by the members of City Council. City Council determines the needs to be addressed and the degree of service to be provided by the administrative branch of city government.

In 2005 Mayor Charles Worley signed the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement and in 2006 the City Council created the Sustainable Advisory Committee on Energy and the Environment. In 2007 the Council became the first city on the East Coast to commit to building all municipal buildings to LEED Gold Standards and to achieve 80 percent energy reduction of 2001 standards by 2040. Also in 2007 the Council signed an agreement with Warren Wilson College stating the intent of the city and college to work together toward climate partnership goals.

Controversy

In 2009, a group of Asheville citizens challenged the legitimacy of Cecil Bothwell's election to the City Council,[32] citing the North Carolina Constitution, which does not permit atheists to hold public office.[33] Bothwell has described himself as a "post theist" rather than an atheist[34] and is a member of a local Unitarian Universalist congregation. The opponents to his election never filed suit. In response to the charge, legal scholars explained that the U.S. Supreme Court held in Torcaso v. Watkins that religious tests for political office are unconstitutional.[35] Mr. Bothwell served his four-year Council term and was re-elected in 2013.[36]

While the city council elections are non-partisan, party politics may enter into play with both Republican and Democratic counterparts backing their registered members candidacy. An effort by the council to return to partisan elections was defeated by voters in a referendum held in November 2007.

- Current elected officials[37]

- Mayor: Esther Manheimer

- Vice-Mayor: Gewn Wisler

- Council: Cecil Bothwell

- Council: Brian Haynes

- Council: Julie Mayfield

- Council: Gordon Smith

- Council: Keith Young

State government

In the North Carolina Senate, Terry Van Duyn (D-Asheville) and Tom Apodaca (R-Hendersonville) both represent parts of Buncombe County. Van Duyn represents most of the city of Asheville. Apodaca represents a small portion of the southern part of Asheville.[38]

In the North Carolina House of Representatives, Susan Fisher (D-Asheville), John Ager (D-Asheville), and Brian Turner (D-Asheville) all represent parts of the county.[39] All three of them represent parts of the city, although the majority of it is in Fisher's district.

Federal government

In the 2012 presidential election, Barack Obama won the entirety of Buncombe County with 55% of the vote. Obama has visited the city on a few occasions.[40] In April 2010, he and his family vacationed in the city; it was the first time he visited since October 5, 2008.[41]

North Carolina is represented in the United States Senate by Richard Burr (R-Winston-Salem) and Thom Tillis (R-Greensboro). The city of Asheville is based in both North Carolina's 10th congressional district and North Carolina's 11th congressional district, represented by Patrick McHenry (R-Gaston County) and Mark Meadows (R-Jackson County), respectively.

Education

Public Asheville City Schools include Asheville High School (known as Lee H Edwards High School 1935–1969), School of Inquiry and Life Sciences at Asheville, Asheville Middle School, Claxton Elementary, Randolph Learning Center, Hall Fletcher Elementary, Isaac Dickson Elementary, Ira B. Jones Elementary and Vance Elementary. Asheville High has been ranked by Newsweek magazine as one of the top 100 high schools in the United States. The Buncombe County School System operates high schools, middle schools and elementary schools both inside and outside the city of Asheville. Clyde A. Erwin High School, T C Roberson High School and A. C. Reynolds High School are three Buncombe County schools located in Asheville.

Asheville was formerly home to one of the only Sudbury schools in the Southeast, Katuah Sudbury School. It is also home to several charter schools, including Francine Delany New School for Children (one of the first charter schools in North Carolina), ArtSpace Charter School, and Evergreen Community Charter School, an Outward Bound-Expeditionary Learning School, recognized as one of the most environmentally conscious schools in the country.[42]

Two private residential high schools are located in the Asheville area: the all-male Christ School (located in Arden) and the co-educational Asheville School. Other private schools include Carolina Day School, Veritas Christian Academy and Asheville Christian Academy.

Colleges

Asheville and its surrounding area have several institutions of higher education:

- Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College (Asheville)

- Black Mountain College (Black Mountain: 1933–1957)

- Shaw University College of Adult and Professional Education or C.A.P.E.

- Brevard College (Brevard)

- Mars Hill University (Mars Hill)

- Montreat College (Montreat)

- University of North Carolina at Asheville (Asheville)

- Warren Wilson College (Swannanoa)

- Western Carolina University (Cullowhee)

- Blue Ridge Community College (Flat Rock)

- South College - Asheville (Asheville)

Transportation

Asheville is served by Asheville Regional Airport in nearby Fletcher, North Carolina, and by Interstate 40, Interstate 240, and Interstate 26. A milestone was achieved in 2003 when Interstate 26 was extended from Mars Hill (north of Asheville) to Johnson City, Tennessee, completing a 20-year half-billion dollar construction project through the Blue Ridge Mountains. Work continues to improve Interstate 26 from Mars Hill to Interstate 40 by improving U.S. Route 19 and U.S. Route 23 and the western part of Interstate 240. This construction will include a multimillion-dollar bridge to cross the French Broad River.[43]

The city operates Asheville Redefines Transit, which consists of sixteen bus lines[44] providing service throughout the City of Asheville and to Black Mountain, North Carolina.

The Norfolk Southern Railway passes through the city, though passenger service is currently not available in the area.

Public services and utilities

The residents of Asheville are served by the Buncombe County Public Libraries, consisting of 11 branches located throughout the County with the headquarters and central library, Pack Memorial Library, being located downtown.[45] The system also includes a law library in the Buncombe County Courthouse and a genealogy and local history department located in the central library.

Drinking water in Asheville is provided by the Asheville water department. The water system consists of three water treatment plants, more than 1,600 miles (2,600 km) of water lines, 30 pumping stations and 27 storage reservoirs.[46]

Sewer services are provided by the Metropolitan Sewerage District of Buncombe County, power provided by Duke Energy, and natural gas is provided by PSNC Energy.

Asheville offers public transit through the ART (Asheville Redefines Transit) bus service that operates across the City of Asheville and to the town of Black Mountain. Routes originate from a central station located at 49 Coxe Avenue.[47]

Sustainability and environmental initiatives

The city of Asheville is home to a Duke Energy Progress coal power plant near Lake Julian. This power plant is designated as having Coal Combustion Residue Surface Impoundments with a High Hazard Potential by the EPA.[48] In 2012 a Duke University study found high levels of arsenic and other toxins in North Carolina lakes and rivers downstream from the Asheville power plants coal ash ponds. Samples collected from coal ash waste flowing from the ponds at the Duke Energy Progress plant to the French Broad River in Buncombe County contained arsenic levels more than four times higher than the EPA drinking water standard, and levels of selenium 17 times higher than the agency's standard for aquatic life.[49] In March 2013 the State of North Carolina sued Duke Energy Progress in order to address similar environmental compliance issues. In July 2013 Duke Energy Corp. and North Carolina environmental regulators proposed a settlement in the lawsuit that stated coal ash threatened Asheville's water supply. The settlement called for Duke to assess the sources and extent of contamination at the Riverbend power plant in Asheville. Duke would be fined $99,100 if the settlement is approved.[50] Following the coal ash spill in Eden, NC resulting in 82,000 tons of coal ash leaking into the Dan River, the North Carolina DENR cancelled all previous settlements with Duke Energy. Duke said a stormwater drainage pipe under the utility's Dan River Steam Station lagoon ruptured Feb. 2, allowing ash slurry to pour into the river. Duke Energy faces future legislation by Tom Apodaca, republican NCGA Senate leader forcing them to clean up their south Asheville coal ash ponds. Tom Apodaca expects the legislation will be filed as soon as the General Assembly returns to session in May 2014. Apodaca expects the ponds will be cleaned up in 5–10 years under his law.[51]

The city of Asheville claims a clear focus on sustainability and the development of a green economy. For Asheville, this goal is defined in their Sustainability Management Plan as: "Making decisions that balance the values of environmental stewardship, social responsibility and economic vitality to meet our present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs."[52] As part of the Zero Waste AVL initiative, which began in 2012, each resident receives "Big Blue," a rolling cart in which they can put all of their materials unsorted. Residents can recycle a great variety of materials and "in this first year of the program 6.30% of waste was diverted from the landfill for recycling."[53]

The Asheville City Council's goal is to reduce the overall carbon footprint 80% by the year 2030. This means 4% or more reduction per year.[54] In 2009 the reduction was made when the "City installed over 3,000 LED street lights, managed its water system under ISO 14001 standards for environmental management, improved the infrastructure and management of many of its buildings, and switched many employees to a 4-day work week (which saves emissions from commuting)."[52] Asheville is recognized by the Green Restaurant Association as the first city in the U.S. to be a Green Dining Destination (significant density of green restaurants).[55]

Local culture

Music

Live music is a significant element in the tourism-based economy of Asheville and the surrounding area. Seasonal festivals and numerous nightclubs and performance venues offer opportunities for visitors and locals to attend a wide variety of live entertainment events.[56]

Asheville has a strong tradition of street performance and outdoor music, including festivals, such as Bele Chere and the Lexington Avenue Arts & Fun Festival (LAAFF). One event is "Shindig on the Green," which happens Saturday nights during July and August on City/County Plaza. By tradition, the Shindig starts "along about sundown" and features local bluegrass bands and dance teams on stage, and informal jam sessions under the trees surrounding the County Courthouse. The "Mountain Dance & Folk Festival" started in 1928 by Bascom Lamar Lunsford is said to be the first event ever labeled a "Folk Festival". Another popular outdoor music event is "Downtown After 5," a monthly concert series held from 5 pm till 9 pm that hosts popular touring musicians as well as local acts. A regular drum circle, organized by residents in Pritchard Park, is open to all and has been a popular local activity every Friday evening. It is also home of the Moog Music Headquarters.[57]

Asheville also plays host to the Warren Haynes Christmas Jam, an annual charity event which raises money for Habitat For Humanity, and attracts nationally touring acts; in addition to regular performers Haynes himself, and the band he plays with, Gov't Mule, past acts include The Allman Brothers Band, Dave Matthews Band, Ani Difranco, Widespread Panic. Other big acts that have played the Asheville area in recent years are bands such as Dawes, Porcupine Tree, Broken Social Scene, Ween, the Avett Brothers, Gillian Welch, Cat Power, Ghost Mice, Loretta Lynn, the Disco Biscuits, STS9, Pretty Lights, Primus, M. Ward and the Mountain Goats. DJ music, as well as a small, but active, dance community are also components of the downtown musical landscape. The town is also home to the Asheville Symphony Orchestra and the Asheville Lyric Opera and there are a number of bluegrass, country, and traditional mountain musicians in the Asheville area. A residency at local music establishment the Orange Peel by the Smashing Pumpkins in 2007, along with the Beastie Boys in 2009, brought national attention to Asheville.[58] The Seattle based rock band Band of Horses have also recorded their last two albums at Echo Mountain Studios in Asheville, as have the Avett Brothers (who have also traditionally played a New Year's Eve concert in Asheville). Christian vocal group the Kingsmen originated in Asheville.

Sports

Current teams

| Name | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville Tourists | Baseball | 1897 | South Atlantic League | McCormick Field |

| Asheville City SC | Soccer | 2016 | National Premier Soccer League | Memorial Stadium |

Previous teams

| Name | Sport | Founded | League | Venue | Years in Asheville |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville Smoke | Ice hockey | 1991 | United Hockey League | Asheville Civic Center | 1998–2002 |

| Asheville Aces | Ice hockey | 2004 | Southern Professional Hockey League | Asheville Civic Center | 2004 |

| Asheville Altitude | Basketball | 2001 | NBA Development League | Asheville Civic Center | 2001–2005 |

Other sports

Area colleges and universities, such as the University of North Carolina at Asheville, compete in sports. UNCA's sports teams are known as the Bulldogs and play in the Big South Conference. The Fighting Owls of Warren Wilson College participate in mountain biking and ultimate sports teams. The college is also home of the Hooter Dome, where the Owls play their home basketball games. The Civic Center is home to the Blue Ridge Rollergirls, an up-and-coming team in the sport of Women's Flat-Track Roller Derby.

Recreational sports

Asheville is a major hub of whitewater recreation, particularly whitewater kayaking, in the eastern US. Many kayak manufacturers have their bases of operation in the Asheville area.[59] Some of the most distinguished whitewater kayakers live in or around Asheville.[60] In its July/August 2006 journal, the group American Whitewater named Asheville one of the top five US whitewater cities.[60] Asheville is also home to numerous Disc Golf courses. Soccer is another popular recreational sport in Asheville. Many games are held at Azalea Park. HFC is the local soccer club in Asheville. The Asheville Hockey League provides opportunities for youth and adult inline hockey at an outdoor rink at Carrier Park. The rink is open to the public and pick-up hockey is also available. The Asheville Civic Center has held recreational ice hockey leagues in the past.

Performing arts

The Asheville Community Theatre was founded in 1946, producing the first amateur production of the Appalachian drama, Dark of the Moon.[61] Soon after, the young actors Charlton Heston and wife Lydia Clarke would take over the small theatre.[62] The current ACT building has two performance spaces – the Mainstage Auditorium, which seats 399 patrons (and named the Heston Auditorium for its most famous alumni); and the more intimate black box performance space 35below, seating no more than 49 patrons.[63]

The North Carolina Stage Company is the only resident professional theatre in the downtown area.

The Asheville Lyric Opera celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2009 with a concert featuring Angela Brown, David Malis, and Tonio Di Paolo, veterans of the Metropolitan Opera.[64] The ALO has typically performed three fully staged professional operas for the community in addition to its vibrant educational program.

Asheville Vaudeville,[65] Asheville's only monthly vaudeville variety show, performs new material each month from local magicians, jugglers, comedians, musicians, stilt-walkers, knife-throwers and more.[66]

Asheville has been home to many small, experimental theatre companies over the years, such as Consider the Following..., Betterdays Productions, Black Swan Theatre, Dark Horse Theatre and Pleiades Productions.[67]

The Asheville capoeira performance movement was solidified with the arrival of world-renowned Mestre Pe de Chumbo to the area in 2006. The capoeira group continues to give performances in the streets, on the stage and during festivals. Due to this group's cumulative efforts in the art of capoeira and in developing community the Asheville Culture Project (ACP) was established in 2010. The ACP is a community arts initiative that offers a space for the integration of cultural performing arts, community and social justice. The cultural center offers the community performances, classes and outreach.

Different Strokes! Performing Arts Collective, founded in 2010, produces and presents theatre that confronts issues of social diversity.[68]

Anam Cara Theatre Company, which opened its doors in West Asheville in February 2011, produces eclectic, avant garde theatre aimed at building community, sparking dialogue, and promoting progressive social change. In February 2013, Anam Cara ended its popular Naked Girls Reading series in protest of policies imposed by Naked Girls Reading's national headquarters that the theatre found "sexist and limiting."[69] Anam Cara has also produced several works of devised theatre.[70]

Alternative performance thrives with events like the Fringe Festival[71] and Americana Burlesque and Sideshow Festival.[72] Several burlesque and boylesque troupes have had success in town, including Blue Skies Burlesque, Bombs Away Cabaret,[73] Bootstraps Burlesque, The Rebelles, Seduction Sideshow.[74] and FTW Burlesque.[75]

Deb au Nare's Burlesque Academy of Asheville[76] was founded in January 2015 and provides classes on burlesque entertainment.

Asheville is the home to Terpsicorps Theatre of Dance and The Asheville Ballet.

Art galleries

The Flood Fine Arts Center is a non-profit contemporary art institution in the River Arts District.

Places of worship

Places of worship in Asheville include the Roman Catholic Basilica of St. Lawrence, the Episcopal Cathedral of All Souls and St. Luke's Church, Conservative Jewish Beth Israel Synagogue, and The Asheville Jewish Learning Institute.[77]

Film and television

Although the area has had a long history with the entertainment industry, recent developments are cementing Asheville as a potential growth area for both film and TV. The Asheville Film Festival has completed its sixth year. However the City of Asheville, which funds the festival, has announced that it will no longer fund the festival. The festival's future is in doubt. The city is also an annual participant in the 48-Hour Film Project.[78]

The city's Public-access television cable TV station URTV broadcast programs from 2006 to 2011.

Films made at least partially in the area include A Breed Apart, Searching for Angela Shelton, Last of the Mohicans (box office #1 film in the U.S.), Being There, My Fellow Americans, Loggerheads, The Fugitive (#1 film), All the Real Girls, Richie Rich, Thunder Road, Hannibal (#1 film), Songcatcher, Patch Adams (#1 film), Nell, Forrest Gump (#1 film), Mr. Destiny, Dirty Dancing, Bull Durham, The Private Eyes, The Swan, The Clearing, House of Poets, The Purple Box, 28 Days and The Hunger Games (box office #1 film).

Locally produced films include Golden Throats of the 20th century and Anywhere, U.S.A.[79], a winning film at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival for Special Jury Prize for Spirit of Independence. Asheville also hosts the ActionFest Film Festival 2010 - 2012. The 2010 inaugural edition included Chuck Norris, who was honored as the first ActionFest "man of action."

The Twin Rivers Media Festival is an independent multi-media film festival held annually in downtown Asheville.[80][81] The festival held its 20th annual event in May 2013.[82]

Media

Asheville is in the "Greenville-Spartanburg-Asheville-Anderson" television DMA and the "Asheville" radio ADI for the city's radio stations.[83]

The primary television station in Asheville is ABC affiliate WLOS-TV Channel 13, with studios in Biltmore Park and a transmitter on Mount Pisgah. Other stations licensed to Asheville include WUNF, a PBS station on Channel 33 and The CW affiliate WYCW on Channel 62. Asheville is also served by the Upstate South Carolina stations of WYFF Channel 4 (NBC), WSPA-TV Channel 7 (CBS), WHNS-TV Channel 21 (FOX), MyNetworkTV station WMYA Channel 40 and 3ABN station Channel 41. SCETV PBS affiliates from the Upstate of South Carolina are generally not carried on cable systems in the North Carolina portion of the DMA.

The Asheville Citizen-Times is Asheville's daily newspaper which covers most of Western North Carolina. The Mountain Xpress is the largest weekly in the area, covering arts and politics in the region. The Asheville Daily Planet is a monthly paper.

WCQS is Asheville's public radio station. It has National Public Radio news and other programs, classical and jazz music.

Friends of Community Radio created WSFM-LP, a volunteer-based, grassroots community radio station. The station is licensed under the "Free Form" format. There are also a variety of broadcasts dedicated to Poetry, Interviews, Selected Topics, Children's Radio, and Comedy. The staff have remote broadcast many local concerts including (but not limited to) Monotonix from Israel, JEFF the Brotherhood from Nashville, Screaming Females from New Jersey, and local acts.

Notable people

Asheville in fiction

- The character Harrison Shepherd, the narrator and protagonist of Barbara Kingsolver's novel The Lacuna lived in Asheville.

- Asheville is featured as a location in the novel One Second After by William R. Forstchen (who lives in the area).

- Asheville is the place Natalie, the heroine in the novel Joshua Spassky by Gwendoline Riley, visits to meet the eponymous hero. She is an admirer of F. Scott Fitzgerald and fascinated by Zelda Fitzgerald who died in a fire at the Highland hospital in Asheville.

- Deborah Smith's novel The Crossroads Cafe is set in the mountains above Asheville, and prominent scenes take place in the city. Sequels to that novel also take place in and around Asheville.

- Angela Blake, a character in the TV series The West Wing was from Asheville.

- The film The Hunger Games was filmed near Asheville.

- Thomas Wolfe's novel Look Homeward, Angel is largely set in Asheville—named Altamont in the book.

- James Dashner's novel The Kill Order takes place in and around Asheville.

- Callum Hunt, the protagonist of Holly Black and Cassandra Clare's The Magisterium Series, is from Asheville. Several prominent scenes take place in the city.

Points of interest

- BB&T Building, tallest structure in Asheville

- Biltmore Estate, largest privately owned house in the United States, and listed as U.S. National Historic Landmark

- Blue Ridge Parkway, America's longest linear park

- Botanical Gardens at Asheville, non-profit botanical gardens initially designed by Doan Ogden

- Grove Park Inn, hotel listed on U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Jackson Building, first skyscraper in western North Carolina

- McCormick Field, one of the oldest minor-league stadiums still in regular use

- North Carolina Arboretum, arboretum and botanical garden located within the Bent Creek Experimental Forest

- Smith-McDowell House, the city's first mansion and oldest surviving house, and the oldest brick structure in Buncombe County

- Thomas Wolfe House, boyhood home of American author Thomas Wolfe, and a U.S. National Historic Landmark

Sister cities

Asheville has seven sister cities:[84]

-

Karpenisi (Greece)

Karpenisi (Greece) -

Karakol, (Kyrgyzstan)

Karakol, (Kyrgyzstan) -

San Cristóbal de las Casas (Mexico)

San Cristóbal de las Casas (Mexico) -

Saumur (France)

Saumur (France) -

Valladolid, Yucatán (Mexico)

Valladolid, Yucatán (Mexico) -

Vladikavkaz (Russia)

Vladikavkaz (Russia) -

Osogbo, (Nigeria)

Osogbo, (Nigeria)

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official precipitation records for Asheville were kept at Aston Park from March 1869 to July 1876, various locations in the city from August 1876 to August 1964, and at Asheville Regional Airport since September 1964. Snow and temperature records began 18 December 1869 and 1 November 1876, respectively. For more information, see ThreadEx.

References

- 1 2 North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. North Carolina Climate & Geography. Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

- ↑ U.S. Travel Weather. North Carolina Weather. Retrieved on 2008-01-13. Archived January 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ David B. Knight Robert E. Davis. Climatology of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States. Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ City-Data.com North Carolina - Climate Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- ↑ Intellicast.com. "MARCH IN THE NORTHEAST". Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ Environmental Modeling Center. EMC MODEL GUIDANCE FOR THE BLIZZARD of 2000. Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- ↑ American Meteorological Society. Weather and Forecasting throughout the Eastern United States. Part III: The Effects of Topography and the Variability of Winter Weather in the Carolinas and Virginia (pg. 11). Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- 1 2 3 State Climate Office of North Carolina. Research on North Carolina Severe Weather. Retrieved on 2008-03-09. Archived December 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ↑ State Climate Office of North Carolina. Overview. Retrieved on 2008-03-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 State Climate Office of North Carolina. General Summary of N.C. Climate. Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

- ↑ NCDC Climate of North Carolina Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- ↑ General Climate Change in North Carolina. Retrieved on 2008-01-17. Archived September 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Duke University. Climate Change and North Carolina Archived September 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2008-01-17.

- ↑ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑ "Station Name: NC ASHEVILLE RGNL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for ASHEVILLE/REGIONAL, NC 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑ "Asheville Neighborhoods". Ashevilleneighborhoods.info. 2010-03-20. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ Chase, Nan K. Asheville: A History, (2007): p.39, 61, 93.

- ↑ "S&W Cafeteria". Asheville's Built Environment. University of North Carolina at Asheville. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007.

- ↑ "The Urban News". The Urban News.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 20, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS Archived May 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Office of Management and Budget, 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ MICROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Office of Management and Budget, 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ COMBINED STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENT CORE BASED STATISTICAL AREAS Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Office of Management and Budget, 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Julia, Flier. "Law Firm in Asheville North Carolina". Fisher Stark. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "City of Asheville Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Ashevillec.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ "About City Government". Ashevillenc.gov. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ Jordan Schrader; Dale Neal (December 8, 2009). "Critics of Cecil Bothwell cite N.C. bar to atheists". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Article VI: Suffrage and Eligibility to Office - Sec. 8. Disqualifications for office.". North Carolina State Constitution. State of North Carolina. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

The following persons shall be disqualified for office: First, any person who shall deny the being of Almighty God.

- ↑ "Critics of Cecil Bothwell cite N.C. bar to atheists". The Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ↑ "Asheville councilman atheism debate goes viral: Cecil Bothwell gets wide audience". citizen-times.com.

- ↑ "Wisler, Smith, Bothwell win council seats". Asheville Citizens-Times. 5 November 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Meet City Council". Ashevillenc.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- ↑ "United States - North Carolina - NC State Senate - NC State Senate 48". Our Campaigns. 2007-05-10. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ NC General Assembly webmasters. "North Carolina General Assembly - Buncombe County Representation (2013-2014 Session)". Ncleg.net. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ James, Frank (2011-10-17). "Obama Hearts North Carolina But It May Have Lost That Loving Feeling : It's All Politics". NPR. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ Wing, Nicholas (16 April 2010). "Obama Vacation: First Family To Visit Asheville, North Carolina". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Evergreen Community Charter School, Asheville North Carolina - Evergreen Community Charter School, Asheville North Carolina". Evergreenccs.org. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ "I-26 Connector, Asheville, NC". Public Information Website. North Carolina Department of Transportation. n.d. Archived from the original on July 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

- ↑ "Maps & Schedules". ashevillenc.gov.

- ↑ "Libraries - Branch Locations". Buncombe County. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Water Production". City of Asheville, NC. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Asheville Transit". City of Asheville. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) - Surface Impoundments with High Hazard Potential Ratings".

- ↑ "Duke University: Progress Energy plant polluting French Broad River,October 15, 2012".

- ↑ "NC files new lawsuits against Duke Energy today, August 16, 2013".

- ↑ "Local News - The Asheville Citizen-Times - citizen-times.com". The Asheville Citizen-Times.

- 1 2 "Sustainability Management Plan" (PDF). Ashevillenc.gov. August 2009. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ "Sustainability". Ashevillenc.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ "City of Asheville Carbon Footprint Annual Report : 2011-2012" (PDF). Ashevillenc.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Music pumps up economy, enlivens nightlife"; Michael Flynn; Asheville Citizen-Times; August 22, 2003

- ↑ Dewan, Shaila (Oct 24, 2010). "36 Hours in Asheville". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Rocking the boat". Mountain Xpress.

- 1 2 American Whitewater Journal July/August 2006 (not published on the web yet)

- ↑ "Asheville Community Theatre » PRODUCTION HISTORY". Ashevilletheatre.org. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "Asheville Community Theatre". Ashevilleguidebook.com. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ "Asheville Community Theatre | Asheville, NC's Official Travel Site". Explore Asheville. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑

- ↑ "ashevillevaudeville.com". ashevillevaudeville.com. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ "Arts". Mountain Xpress.

- ↑ Williams, Margaret (2001). Act of faith. Mountain Xpress.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Hartman, Kim. (2013). Naked Girls Not Reading. WNC Woman.

- ↑ Kiss, Tony. (2011). West Asheville's entertainment district is booming. Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ↑ "The Asheville Fringe Arts Festival - Asheville Fringe Arts Festival". Asheville Fringe Arts Festival.

- ↑ "Americana Burlesque & Sideshow Festival". absfest.com.

- ↑ "Bombs Away Cabaret!". Bombs Away Cabaret!.

- ↑ Samuels, Steven. (2010). Vaudeville! Burlesque! Cabaret! Mountain Xpress.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Burlesque Academy of Asheville". debaunare.com.

- ↑ "Religious services, festivals: Asheville faith news". Citizen-Times. October 23, 2015.

- ↑ "48-Hour Film Festival Asheville". 48hourfilm.com. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ "Anywhere USA Sundance Award". History.sundance.org. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ↑ staff (May 18, 2012). "Asheville's River Arts District hosts 19th annual Twin Rivers Media Festival beginning Friday" (PDF). ashevillenc.gov. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ↑ Moe, Jack. "The Vision of the Twin Rivers Media Festival-Asheville, NC". Appalachian Getaways. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ↑ Motsinger, Carol (May 9, 2013). "20th annual Twin Rivers Media Festival opens May 17". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Market Ranks". arbitron.com.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asheville, North Carolina. |

- Official Asheville, NC website

- Asheville, North Carolina, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Asheville travel guide by Asheville Convention and Visitors Bureau

-

Asheville travel guide from Wikivoyage

Asheville travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Climate data for Cape Hatteras (Billy Mitchell Airport), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1898–present[lower-alpha 2] |

|---|

| Climate data for Charlotte, North Carolina (Charlotte-Douglas Int'l), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 3] extremes 1878–present[lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

82 (28) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 69.7 (20.9) |

72.8 (22.7) |

81.1 (27.3) |

86.3 (30.2) |

90.0 (32.2) |

94.4 (34.7) |

96.9 (36.1) |

96.0 (35.6) |

91.1 (32.8) |

84.9 (29.4) |

78.0 (25.6) |

70.4 (21.3) |

98.0 (36.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 50.7 (10.4) |

55.0 (12.8) |

63.1 (17.3) |

71.9 (22.2) |

78.9 (26.1) |

86.0 (30) |

89.0 (31.7) |

87.5 (30.8) |

81.3 (27.4) |

71.8 (22.1) |

62.4 (16.9) |

52.9 (11.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

39.3 (4.1) |

46.9 (8.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

64.5 (18.1) |

68.1 (20.1) |

67.2 (19.6) |

60.4 (15.8) |

48.8 (9.3) |

39.2 (4) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

48.7 (9.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.2 (−9.9) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

32.9 (0.5) |

43.3 (6.3) |

55.9 (13.3) |

62.0 (16.7) |

60.6 (15.9) |

48.7 (9.3) |

34.6 (1.4) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

11.3 (−11.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

−5 (−21) |

4 (−16) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

45 (7) |

53 (12) |

50 (10) |

38 (3) |

24 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

−5 (−21) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.41 (86.6) |

3.32 (84.3) |

4.01 (101.9) |

3.04 (77.2) |

3.18 (80.8) |

3.74 (95) |

3.68 (93.5) |

4.22 (107.2) |

3.24 (82.3) |

3.40 (86.4) |

3.14 (79.8) |

3.25 (82.6) |

41.63 (1,057.4) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.1 (5.3) |

1.2 (3) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.3 (0.8) |

4.3 (10.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 109.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65.7 | 61.8 | 61.5 | 59.3 | 66.9 | 69.6 | 72.2 | 73.5 | 73.3 | 69.9 | 67.6 | 67.3 | 67.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 173.3 | 180.3 | 234.8 | 269.6 | 292.1 | 289.2 | 290.0 | 272.9 | 241.4 | 230.5 | 178.4 | 168.5 | 2,821 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55 | 59 | 63 | 69 | 67 | 66 | 66 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 58 | 55 | 63 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[3][4][5] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Greensboro, North Carolina (Piedmont Triad Int'l), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 5] extremes 1903–present[lower-alpha 6] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.0 (20) |

71.1 (21.7) |

79.6 (26.4) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.0 (31.7) |

93.5 (34.2) |

95.5 (35.3) |

94.6 (34.8) |

90.2 (32.3) |

83.8 (28.8) |

76.2 (24.6) |

68.6 (20.3) |

96.7 (35.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 48.3 (9.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.9 (16.1) |

70.2 (21.2) |

77.5 (25.3) |

84.8 (29.3) |

87.9 (31.1) |

86.3 (30.2) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.3 (21.3) |

60.8 (16) |

50.7 (10.4) |

69.2 (20.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 29.5 (−1.4) |

32.4 (0.2) |

39.1 (3.9) |

47.3 (8.5) |

56.1 (13.4) |

65.3 (18.5) |

69.1 (20.6) |

68.0 (20) |

60.6 (15.9) |

48.8 (9.3) |

39.6 (4.2) |

32.0 (0) |

49.1 (9.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 11.2 (−11.6) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

41.3 (5.2) |

53.0 (11.7) |

59.2 (15.1) |

58.3 (14.6) |

46.3 (7.9) |

33.3 (0.7) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

16.0 (−8.9) |

8.2 (−13.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−4 (−20) |

5 (−15) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

48 (9) |

45 (7) |

35 (2) |

20 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−1 (−18) |

−8 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.06 (77.7) |

2.96 (75.2) |

3.73 (94.7) |

3.57 (90.7) |

3.38 (85.9) |

3.73 (94.7) |

4.48 (113.8) |

3.88 (98.6) |

4.19 (106.4) |

3.13 (79.5) |

3.11 (79) |

2.98 (75.7) |

42.2 (1,071.9) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.4 (8.6) |

2.4 (6.1) |

0.8 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.8 (2) |

7.5 (19.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 9.4 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 9.2 | 110.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 4.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.4 | 64.0 | 62.7 | 60.9 | 69.8 | 72.7 | 75.4 | 76.4 | 75.9 | 72.2 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 69.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.6 | 174.5 | 228.6 | 246.1 | 261.9 | 270.3 | 270.1 | 249.3 | 223.9 | 218.6 | 174.7 | 163.3 | 2,650.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55 | 57 | 62 | 63 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 59 | 60 | 63 | 57 | 54 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[6][7][8] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Raleigh–Durham International Airport, North Carolina (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 7] extremes 1887–present[lower-alpha 8]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

84 (29) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

81 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.1 (21.7) |

74.3 (23.5) |

81.8 (27.7) |

87.1 (30.6) |

90.8 (32.7) |

96.0 (35.6) |

97.5 (36.4) |

96.8 (36) |

91.9 (33.3) |

86.0 (30) |

78.9 (26.1) |

72.3 (22.4) |

99.0 (37.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 50.9 (10.5) |

55.2 (12.9) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.4 (22.4) |

79.6 (26.4) |

87.1 (30.6) |

90.2 (32.3) |

88.4 (31.3) |

82.1 (27.8) |

72.6 (22.6) |

63.6 (17.6) |

53.6 (12) |

71.7 (22.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.0 (−0.6) |

33.8 (1) |

39.9 (4.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

56.5 (13.6) |

65.8 (18.8) |

69.9 (21.1) |

68.6 (20.3) |

61.7 (16.5) |

49.8 (9.9) |

40.8 (4.9) |

33.3 (0.7) |

50.0 (10) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 12.4 (−10.9) |

17.6 (−8) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

41.8 (5.4) |

52.9 (11.6) |

59.7 (15.4) |

58.1 (14.5) |

46.7 (8.2) |

32.7 (0.4) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

10.0 (−12.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−2 (−19) |

11 (−12) |

23 (−5) |

29 (−2) |

38 (3) |

48 (9) |

46 (8) |

37 (3) |

19 (−7) |

11 (−12) |

0 (−18) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.50 (88.9) |

3.23 (82) |

4.11 (104.4) |

2.92 (74.2) |

3.27 (83.1) |

3.52 (89.4) |

4.73 (120.1) |

4.26 (108.2) |

4.36 (110.7) |

3.25 (82.6) |

3.12 (79.2) |

3.07 (78) |

43.34 (1,100.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.9 (7.4) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.6 (1.5) |

6.1 (15.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 10.5 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 9.4 | 114.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.5 | 64.1 | 63.0 | 61.7 | 71.1 | 73.6 | 76.0 | 77.9 | 77.1 | 73.3 | 69.1 | 68.5 | 70.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 163.8 | 173.1 | 228.9 | 250.7 | 258.4 | 267.7 | 259.5 | 239.6 | 217.6 | 215.4 | 174.0 | 157.6 | 2,606.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 57 | 62 | 64 | 59 | 61 | 58 | 57 | 58 | 62 | 56 | 52 | 59 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990),[6][9][10] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Climate

- Climate change

- Climatology

- List of North Carolina hurricanes

- List of North Carolina weather records

- List of wettest known tropical cyclones in North Carolina

- Meteorology

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official temperature and precipitation records for Cape Hatteras were kept at Hatteras from January 1893 to February 1957, and at Billy Mitchell Airport since March 1957. Snowfall and snow depth records date to 1 January 1908 and 1 January 1948 respectively.[1] For more information, see ThreadEx.</ref>

ay

i Month

a Jan

i Feb

y Mar

n Apr

9 May

} Jun

Jul

r Aug

Sep

g Oct

p Nov

r Dec

nge near {{convert|50|F|C}}. (HowevYear

rtex or "cold blast" can signi

icantly bring down averag Record high °F (°C)

in the winters of 2014 and 2015.)<ref name="US 75

(24) U.S. Travel Weather. [http://www.ustravelweath 76

(24) north-carolina/ North Carolina Weather.] Retri 82

(28) -13. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org 89

(32) 2115/http://www.ustravelweather.com/weather-no 91

(33) date=January 29, 2008 }}</ref> In the month of 97

(36) s an average of 4.21 inches. == Precipitation 96

(36) average of forty-five inches of rain a year ( 94

(34) untains). July storms account for much of this 92

(33) As much as 15% of the rainfall during the wa 89

(32) e Carolinas can be attributed to tropical cycl 81

(27) B. Knight Robert E. Davis. [http://bellwether 78

(26) content/n562284522t561n5/ Climatology of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in t 97

(36) tates.]{{dead link|date=Novemb r 2016 |bot=InternetArchi Mean maximum °F (°C) es }} Retrieved on 2008-02-29.</ref> Mountain 69.1

(20.6) snow in the fall and winter.<ref name="NCSOS"/ 68.7

(20.4) the southwest drop an average of {{convert|80| 72.9

(22.7) ation on the western side of the mountains, wh 78.1

(25.6) acing slopes average less than half that amoun 83.5

(28.6) ta">City-Data.com [http://www.city-data.com/st 88.9

(31.6) -Climate.html North Carolina - Climate] Retrie 90.6

(32.6) /ref> === Snow === [[File:1993 Storm of the C 90.0

(32.2) orth Carolina snowfall.jpg|thumb|left|200px|A 87.5

(30.8) heville, North Carolina|Asheville]], [[North C 82.5

(28.1) snowfall from the [[Storm of the Century (199 76.8

(24.9) e Century]].]] [[Snow]] in North Carolina is s 71.1

(21.7) sis in the mountains. North Carolina averages {{convert|5|in|mm}} of sn 91.4

(33) lso varies greatly across the tate. Along the coast, mo Average high °F (°C) than {{convert|2|in|mm}} per year while the s 52.2

(11.2) gh averages {{convert|7.5|in|mm}}. Farther wes 53.5

(11.9) riad, the average grows to approximately {{con 58.6

(14.8) e Charlotte area averages approximately {{conv 66.3

(19.1) e mountains in the west act as a barrier, prev 73.7

(23.2) rms from entering the [[Piedmont (United State 81.0

(27.2) snow does make it past the mountains, it is u 84.6

(29.2) seldom on the ground for more than two or thr 84.1

(28.9) everal storms have dropped {{convert|18|in|mm} 79.9

(26.6) ithin normally warm areas. The [[Storm of the 72.0

(22.2) Storm of the Century]] that lasted from March 64.0

(17.8) ected locales from [[Canada]] to [[Central Ame 55.9

(13.3) a significant amount of snow to North Carolina. [[Newfound Gap]] recei 68.9

(20.5) n|m}} of snow with drifts more than {{convert|5|ft|m}}, Average low °F (°C) l]] measured over {{convert|4|ft|m}} of snow w 38.7

(3.7) nvert|14|ft|m}}.<ref name = intellamounts>{{ci 40.0

(4.4) p://www.intellicast.com/Almanac/Northeast/Marc 44.6

(7) CH IN THE NORTHEAST | author = Intellicast.com 52.6

(11.4) 8-02-09}}</ref> Most of the northwestern par 60.5

(15.8) ived somewhere between {{convert|2|ft|m}} an { 69.3

(20.7) f snow. Another significant snowfall hit the 73.6

(23.1) uary 2000, when more than {{convert|20|in|mm}} 72.9

(22.7) [[Environmental Modeling Center]]. [http://www 69.0

(20.6) mmb/research/blizz2000/ EMC MODEL GUIDANCE FO 59.7

(15.4) 000.] Retrieved on 2008-02-09.</ref> There wa 51.2

(10.7) fall totaling {{convert|18|in|mm}} that hit th 42.7

(5.9) just before Christmas in 1989, with little snow measured west of [[Inte 56.3

(13.5) I-95]]. Most of the major snow that impact areas east o Mean minimum °F (°C) rom [[extratropical cyclone]]s which approach 23.1

(−4.9) ss Georgia and South Carolina and move offshor 26.2

(−3.2) the storms track too far east, the snow will 30.5

(−0.8) astern part of the state. If the [[cyclone]]s 38.0

(3.3) e coast, warm air will get drawn into eastern 47.1

(8.4) to increasing flow off the milder [[Atlantic 57.4

(14.1) rain/snow line well inland with heavy snow re 64.5

(18.1) dmont. If the storm tracks inland into eastern 63.8

(17.7) e rain/snow line ranges between Raleigh and Gr 57.5

(14.2) "AMS">American Meteorological Society. [http:/ 45.2

(7.3) m/archive/1520-0434/10/1/pdf/i1520-0434-10-1-4 36.5

(2.5) Forecasting throughout the Eastern United Stat 28.0

(−2.2) ffects of Topography and the Variability of Winter Weather in the Carol 21.2

(−6) .] Retrieved on 2008-02-09. {{ ead link| date=June 2010 Record low °F (°C) > == Tropical cyclones == [[Image:Hurricane F 6

(−14) pg|left|200px|thumb|[[Hurricane Fran]]]] {{mai 11

(−12) f North Carolina hurricanes}} Located along th 19

(−7) t, North Carolina is no stranger to hurricanes 26

(−3) es that come up from the [[Caribbean Sea]] mak 39

(4) ast of eastern America, passing by North Carol 44

(7) loyd1999 accumulations bilingual.gif|thumb|rig 52

(11) all from Floyd]] On October 15, 1954, [[Hurric 56

(13) uck North Carolina, at that time it was a [[Li 45

(7) 4 Atlantic hurricanes|category 4 hurricane]] 32

(0) affir-Simpson Hurricane Scale]]. Hazel caused 22

(−6) mage due to its strong winds. A weather stati 12

(−11) nd, North Carolina|Oak Island]] reported [[maximum sustained wind]]s of 6

(−14) }, while in [[Raleigh, North C rolina|Raleigh]] winds of Average precipitation inches (mm) The hurricane caused 19 deaths and significa 5.24

(133.1) person at [[Long Beach, North Carolina|Long B 4.02

(102.1) "of the 357 buildings that existed in the town 4.77

(121.2) estroyed and the other five damaged". Hazel w 3.64

(92.5) e most destructive storm in the history of Nor 3.57

(90.7) 989 report.<ref name="RONCSW">State Climate Of 4.03

(102.4) na. [http://www.dem.dcc.state.nc.us/mitigation 4.99

(126.7) man.pdf Research on North Carolina Severe Weat 6.93

(176) 2008-03-09. {{webarchive |url=https://web.arc 6.25

(158.8) 6053043/http://www.dem.dcc.state.nc.us/mitigat 5.38

(136.7) /raman.pdf |date=December 16, 2005 }}</ref> I 4.95

(125.7) Fran]] made landfall in North Carolina. As a 4.27

(108.5) ne]], Fran caused a great deal of damage, mainly through winds. Fran's 58.04

(1,474.2) re {{convert|115|mph|km/h}}, w ile North Carolina's coas Average snowfall inches (cm) |m}} to {{convert|12|ft|m}} above sea level. T 0.3

(0.8) ge caused by Fran ranged from $1.275 to $2&nbs 0.1

(0.3) h Carolina.<ref name="RONCSW"/> === Rain === 0

(0) ccompany [[tropical cyclones]] and their remna 0

(0) e northeast from the [[Gulf of Mexico]] coastl 0

(0) as inland from the western subtropical [[Atlan 0

(0) Over the past 30 years, the wettest tropical 0

(0) rike the coastal plain was [[Hurricane Floyd]] 0

(0) 1999, which dropped over {{convert|24|in|mm}} 0

(0) north of [[Southport, North Carolina|Southport 0

(0) azel and Fran, the main force of destruction w 0

(0) pitation. Before Hurricane Floyd reached North 1.3

(3.3) ate had already received large amounts of rain from [[Hurricane Dennis 1.7

(4.3) less than two weeks before Flo d. This saturated much o Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) [[floods]]. Over 35 people died from Floyd.<r 10.6 e="RONCSW"/> In the mountains, [[Hurricane Fra 10.5 of September 2004 was nearly as wet, bringing 10.3 {{convert|23|in|mm}} of rainfall to [[Mount Mi 8.8 l]].{{Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southea 8.8 United States}} [[Image:Tornado Alley.gif|th 10.1 ght|200px|Tornado activity in the United State 11.6 == Severe weather == In most years, the greate 11.2 ther-related economic loss incurred in North C 9.6 na is due to severe weather spawned by summer 8.9 erstorms. These storms affect limited areas, 9.6 their hail and wind accounting for an average 10.4 loss of over US$5 million.<ref>State Climate Office of North Caro 120.4 w.nc-climate.ncsu.edu/climate/ cclimate.html Overview.] Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) ay seeing the most tornadoes on average a mont 0.4 h 5. June, July and August all have an average 0.3 tornadoes with an increase to 4 average torna 0 s a month in September. It is through Septembe 0 nd into early November when North Carolina can 0 pically expect to see that smaller, secondary, 0 vere weather season. While severe weather seas 0 is technically from March through May, tornado 0 have touched down in North Carolina in every m 0 h of the year. [http://origin.digtriad.com/we 0 erexplainers/article/279909/390/Two-Tornado-Se 0 ns-In-North-Carolina] == Seasonal conditions 0.3 == Winter === In winter, North Carolina is protected by the [[Appalachi 1.0 on the western front. Cold fr nts from [[Canada]] and t Average relative humidity (%) t past the towering mountains. Cold winds make 75.3 ross the peaks once or twice a year and force 74.3 mperatures to drop to about {{convert|10|°F|°C 74.1 on}} in central North Carolina. Although tempe 72.3 s below zero degrees Fahrenheit are extremely 77.3 utside of the mountains. The coldest ever reco 79.0 emperature in North Carolina was {{convert|-34 80.9 |abbr=on}} on [[January 1985 Arctic outbreak|J 80.6 21, 1985]], at [[Mount Mitchell]]. The winter 78.5 ratures on the coast are mostly due to the Atl 75.8 Ocean and the [[Gulf Stream]].<ref name="NCCLI 75.1 e Climate Office of North Carolina. [http://ww 75.1 limate.ncsu.edu/climate/ncclimate.html General Summary of N.C. Climate. 76.5 ie ed on 2008- 1-13.</ref> The average ocean emperature in [[Southport Mean monthly sunshine hours gher than the average ocean temperature in Mai 153.7 ng July.<ref name="NCCLI"/> Snow is common in 162.8 ntains, although many ski resorts use snowmaki 224.8 pment to make sure there is always snow on the 261.3 .<ref name="NCCLI"/> North Carolina's relative 278.3 ty is highest in the winter.<ref name="NCCLI"/ 272.4 Spring === Tornadoes are most likely early in 282.9 ing. The month of May experiences the greates 267.1 in temperatures. During the spring, there are 233.0 ys and cool nights in the piedmont. Temperatur 207.2 somewhat cooler in the mountains and warmer, p 170.8 arly at night, near the coast.<ref name="NCCLI 142.8 th Carolina's humidity is lowest in the Spring.<ref name="NCCLI"/> === 2,657.1 == [[Image:Har is Lake Highlands.jpg|thumb|20 px|[[Harris Lake (Highlan Percent possible sunshine North Carolina|Highlands]], [[North Carolina] 49 ring [[Autumn|Fall]].]] North Carolina experie 53 high summer temperatures. Sometimes, cool, d 61 ir from the north will invade North Carolina f 66 rief periods of time, with temperatures quickl 64 bounding.<ref name="NCclimate">NCDC [http://w 63 ncdc.noaa.gov/climatenormals/clim60/states/Cli 64 _01.pdf/ Climate of North Carolina] Retrieved 64 008-02-09. {{dead link|date=June 2016|bot=med 63 {{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> It remains colder 59 high elevations, with the average summer tempe 55 re in [[Mount Mitchell]] lying at {{convert|68 47 °C}}. Morning temperatures are on average 20 °F (12 °C) lowe 60 an afternoon temperatures, except along the [[East Coast ofSource: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[1][2]<ref name='noaasun'>"WMO Climate Normals for CAPE HATTERAS, NC 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-05-27. - ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official records for Charlotte kept October 1878 to August 1948 at downtown and at Charlotte-Douglas Int'l since September 1948. For more information, see Threadex

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official records for Greensboro have been kept since January 1903; Piedmont Triad Int'l was made the official climatology station in November 1928. For more information, see Threadex

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official records for Raleigh kept January 1887 to 17 May 1944 at downtown and at Raleigh Durham Int'l since 18 May 1944. For more information, see Threadex

References

- 1 2 "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ↑ "Station Name: NC CAPE HATTERAS AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- ↑ "Station Name: NC CHARLOTTE DOUGLAS AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-04.