Glengarry Glen Ross (film)

| Glengarry Glen Ross | |

|---|---|

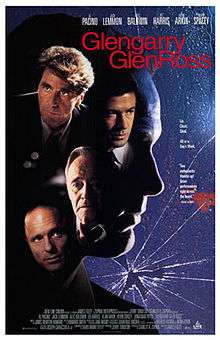

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Foley |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | David Mamet |

| Based on |

Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

| Cinematography | Juan Ruiz Anchía |

| Edited by | Howard Smith |

Production company |

Zupnik Enterprises |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12.5 million |

| Box office | $10.7 million (North America)[1] |

Glengarry Glen Ross is a 1992 American drama, adapted by David Mamet from his 1984 Pulitzer Prize- and Tony-winning play of the same name, and directed by James Foley. The film is set in either New York City[2][3] or Chicago,[4][5][6] and was filmed in New York City.[7] It depicts two days in the lives of four real estate salesmen and how they become desperate when the corporate office sends a trainer to "motivate" them by announcing that, in one week, all except the top two salesmen will be fired. The film, like the play, is notorious for its use of profanity, leading the cast to jokingly refer to the film as "Death of a Fuckin' Salesman."[8] The title of the film comes from the names of two of the real estate developments being peddled by the salesmen characters: Glengarry Highlands and Glen Ross Farms.

The world premiere of the film was held at the 49th Venice Film Festival, where Jack Lemmon, one of the film's stars, was awarded the Volpi Cup for Best Actor. The film was a commercial failure, making only US $10.7 million in North America, just below its $12.5 million budget. Al Pacino was nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor for his work in the film.

Plot

The film depicts two days in the lives of four real estate salesmen who are supplied with names and phone numbers of leads. They use underhanded and dubious tactics to make sales. Many of the leads rationed out by the office manager lack either the money or the desire to actually invest in land.

Blake (Baldwin) is sent by Mitch and Murray, the owners of Premier Properties, to motivate the salesmen. Blake unleashes a torrent of verbal abuse on the men and announces that only the top two sellers will be allowed access to the more promising Glengarry leads and the rest of them will be fired.

Shelley "The Machine" Levene (Lemmon), a once-successful salesman now in a long-running slump and with a chronically ill daughter in the hospital with an unknown medical condition, knows that he will lose his job soon if he cannot generate sales. He tries to convince office manager John Williamson (Spacey) to give him some of the Glengarry leads, but Williamson refuses. Levene tries first to charm Williamson, then to threaten him, and finally to bribe him. Williamson is willing to sell some of the prime leads, but demands cash in advance. Levene cannot come up with the cash and leaves without any good leads.

Meanwhile, Dave Moss (Harris) and George Aaronow (Arkin) complain about Mitch and Murray, and Moss proposes that they strike back at the two by stealing all the Glengarry leads and selling them to a competing real estate agency. Moss's plan requires Aaronow to break into the office, stage a burglary and steal all of the prime leads. Aaronow wants no part of the plan, but Moss tries to coerce him, saying that Aaronow is already an accessory before the fact simply because he knows about the proposed burglary.

At a nearby bar, Ricky Roma (Pacino), the office's top "closer," delivers a long, disjointed but compelling monologue to a meek, middle-aged man named James Lingk (Pryce). Roma does not broach the subject of a Glengarry Farms real estate deal until he has completely won Lingk over with his speech. Framing it as an opportunity rather than a purchase, Roma plays upon Lingk's feelings of insecurity.

The film then skips to the next day when the salesmen come into the office to find that there has been a burglary and the Glengarry leads have been stolen. Williamson and the police question each of the salesmen in private. After his interrogation, Moss leaves in disgust, only after having one last shouting match with Roma. During the cycle of interrogations, Lingk arrives to tell Roma that his wife has told him to cancel the deal. Scrambling to salvage the deal, Roma tries to deceive Lingk by telling him that the check he wrote the night before has yet to be cashed, and that accordingly he has time to reason with his wife and reconsider.

Levene abets Roma by pretending to be a wealthy investor who just happens to be on his way to the airport. Williamson, unaware of Roma and Levene's stalling tactic, lies to Lingk, claiming that he already deposited his check in the bank. Upset, Lingk rushes out of the office, and Roma berates Williamson for what he has done. Roma then enters Williamson's office to take his turn being interrogated by the police.

Levene, proud of a massive sale he made that morning, takes the opportunity to mock Williamson in private. In his zeal to get back at Williamson, Levene accidentally reveals that he knows Williamson lied to Roma minutes earlier about depositing Lingk's check and had left the check on his desk and had not made the bank run the previous night — something only a man who broke into the office would know. Williamson catches Levene's slip of the tongue and compels Levene to admit that he broke into the office. Levene finally caves in and admits that he and Moss conspired to steal the leads. Levene attempts to bribe Williamson to keep quiet about the burglary. Williamson scoffs at the suggestion and tells Levene that the buyers to whom he had made his sale earlier that day are in fact bankrupt and delusional and just enjoy talking to salesmen. Levene, crushed by this revelation, asks Williamson why he seeks to ruin him. Williamson coldly responds, "Because I don't like you."

Levene makes a last-ditch attempt at gaining sympathy from Williamson by mentioning his daughter's health, but Williamson cruelly rebuffs him and leaves to inform the detective about Levene's part in the burglary. Roma walks out of the room as Williamson enters. Unaware of Levene's guilt, Roma talks to Levene about forming a business partnership before the detective starts calling for Levene. Levene walks, defeated, into Williamson's office. Roma then leaves the office to go out for lunch, while Aaronow returns back to his desk to make his sales calls as usual.

Cast

- Al Pacino as Ricky Roma

- Jack Lemmon as Shelley "The Machine" Levene

- Alec Baldwin as Blake

- Alan Arkin as George Aaronow

- Ed Harris as Dave Moss

- Kevin Spacey as John Williamson

- Jonathan Pryce as James Lingk

- Bruce Altman as Larry Spannel

- Jude Ciccolella as the detective

Production

David Mamet's play was first performed in 1983 at the Royal National Theatre, London. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984. That same year, the play made its American debut in Chicago before moving to Broadway. Producer Jerry Tokofsky read the play on a trip to New York City in 1985 at the suggestion of director Irvin Kershner who wanted to make it into a film.[9] Tokofsky saw the play on Broadway and contacted Mamet. Stanley R. Zupnik was a Washington, D.C. based producer of B movies who was looking for a more profitable project. Tokofsky had co-produced two previous Zupnik films. In 1986, Tokofsky told Zupnik about Mamet's play, and Zupnik saw it on Broadway but found the plot confusing. Mamet wanted $500,000 for the film rights and another $500,000 to write the screenplay. Zupnik agreed to pay Mamet’s $1 million asking price, figuring that they could cut a deal with a cable company to bankroll the movie. Because of the uncompromising subject matter and abrasive language, no major studio wanted to finance it, even with movie stars attached. Financing came from cable and video companies, a German television station, an Australian movie theater chain, several banks, and New Line Cinema over the course of four years.[9]

Al Pacino originally wanted to do the play on Broadway, but at the time he was doing another Mamet production, American Buffalo, in London. He expressed interest in appearing in the film adaptation. In 1989, Tokofsky asked Jack Lemmon to act in the movie.[10] During this time, Kershner dropped out to make another movie, as did Pacino. Alec Baldwin, who also attached, left the project over a contract disagreement. James Foley's agent sent Foley Mamet's screenplay in early 1991, but Foley was hesitant to direct because he "wanted great actors, people with movie charisma, to give it watchability, especially since the locations were so restricted".[11] Foley took the screenplay to Pacino, with whom he had been trying to work on a film for years.[12] Foley was hired to direct, only to leave the production as well. By March 1991, Tokofsky contacted Baldwin and begged him to reconsider doing the film. Baldwin's character was specifically written for the actor, to include in the film version, and is not part of the original play. Tokofsky remembers, "Alec said: 'I’ve read 25 scripts and nothing is as good as this. OK. If you make it, I’ll do it'."[9] The two men arranged an informal reading with Lemmon in Los Angeles. Subsequently, the three men organized readings with several other actors, as Lemmon remembers, "Some of the best damn actors you're ever going to see came in and read and I'm talking about names".[12] Tokofsky's lawyer, Jake Bloom, called a meeting at the Creative Artists Agency, who represented many of the actors involved, and asked for their help. CAA showed little interest, but two of their clients – Ed Harris and Kevin Spacey – soon joined the cast.

Because of the film’s modest budget, many of the actors took significant pay cuts. For example, Pacino cut his per-movie price from $6 million to $1.5 million, Lemmon was paid $1 million, Baldwin received $250,000, and so on.[9] This did not stop other actors, like Robert De Niro, Bruce Willis,[9] Richard Gere, and Joe Mantegna,[10] from expressing interest in the film. Mantegna had been in the original Broadway cast and won a Tony Award in 1985 for his portrayal of Roma.

Once the film's cast was assembled, they spent three weeks in rehearsals. With a budget set at $12.5 million, filming began in August 1991 at the Kaufman Astoria Soundstage in Queens, New York and on location in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn over 39 days. Harris remembers, "There were five and six-page scenes we would shoot all at once. It was more like doing a play at times [when] you'd get the continuity going".[12] Alan Arkin said of the script, "What made it [challenging] was the language and the rhythms, which are enormously difficult to absorb".[12] During filming, members of the cast who were not required to be on the set certain days would show up anyway to watch the other actors' performances.[13]

The film's director of photography, Juan Ruiz Anchía, relied on low lighting and shadows with a blues, greens, and reds color scheme for the first part of the film. For the second half, he adhered to a monochromatic blue-grey color scheme.

During the production, Tokofsky and Zupnik had a falling out over money and credit for the film. Tokofsky sued to strip Zupnik of his producer’s credit and share of the producer's fee.[14] Zupnik claimed that he personally put up $2 million of the film’s budget and countersued, claiming that Tokofsky was fired for embezzlement.[14]

Reception

Glengarry Glen Ross had its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where Jack Lemmon won the Volpi Cup for Best Actor.[15] In addition, it was originally slated to be shown at the Montreal Film Festival, but it was necessary to show it out of competition because it was entered into competition at the Venice Film Festival at the same time. Instead, it was given its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.[16] The film opened in wide release on October 2, 1992 in 416 theaters, grossing $2.1 million on its opening weekend. It went on to make $10.7 million in North America,[1] just below its $12.5 million budget.[1]

Reviews were highly positive. The film currently has a rating of 94% on Rotten Tomatoes with a consensus of, "This adaptation of David Mamet's play is every bit as compelling and witty as its source material, thanks in large part to a clever script and a bevy of powerhouse actors."[17] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 80 out of 100, based on 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[6]

Owen Gleiberman gave the film an "A" rating in his review for Entertainment Weekly magazine, praising Lemmon's performance as "a revelation" and describing his character as "the weaselly soul of Glengarry Glen Ross–Willy Loman turned into a one-liner".[18] In his review in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert wrote, "Mamet's dialogue has a kind of logic, a cadence, that allows people to arrive in triumph at the ends of sentences we could not possibly have imagined. There is great energy in it. You can see the joy with which these actors get their teeth into these great lines, after living through movies in which flat dialogue serves only to advance the story".[19] Newsweek magazine's Jack Kroll observed of Alec Baldwin's performance, "Baldwin is sleekly sinister in the role of Blake, a troubleshooter called in to shake up the salesmen. He shakes them up, all right, but this character (not in the original play) also shakes up the movie's toned balance with his sheer noise and scatological fury".[20] In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby praised, "the utterly demonic skill with which these foulmouthed characters carve one another up in futile attempts to stave off disaster. It's also because of the breathtaking wizardry with which Mr. Mamet and Mr. Foley have made a vivid, living film that preserves the claustrophobic nature of the original stage work".[21] In his review for Time, Richard Corliss wrote, "A peerless ensemble of actors fills Glengarry Glen Ross with audible glares and shudders. The play was zippy black comedy about predators in twilight; the film is a photo-essay, shot in morgue closeup, about the difficulty most people have convincing themselves that what they do matters".[22] However, Desson Howe's review in The Washington Post criticized Foley's direction, writing that it "doesn't add much more than the street between. If his intention is to create a sense of claustrophobia, he also creates the (presumably) unwanted effect of a soundstage. There is no evidence of life outside the immediate world of the movie".[23] Movie Room Reviews gave the film 4 stars and said "Director James Foley does a great job of making the film seem claustrophobic, so that the audience almost feels as if it is in the fluorescent lighting of the drab office."[24]

Awards

Jack Lemmon was voted Best Actor by the National Board of Review.[25] Al Pacino was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor but did not win.[26] He was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role but lost to Gene Hackman for Unforgiven; the same year he was nominated and won the Best Actor Oscar for Scent of a Woman.[27] Empire magazine voted the film the 470th greatest film in their "500 Greatest Movies of All Time" list.[28]

Legacy

Lemmon's portrayal of Shelley Levene was a major source of inspiration in the creation of the recurring character Gil Gunderson on The Simpsons.[29] The character borrows many of the mannerisms of Levene, and is often portrayed as an unsuccessful salesman.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 "Glengarry Glen Ross". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Champion, Jared (June 2011). "Hegemonic Masculinity and Blake's "Mission of Mercy": David Mamet's Cinematic Adaptation of Glengarry Glen Ross as Postmodern Satire of Fundamentalist Christianity". Journal of Men, Masculinities and Spirituality. 5 (2): 78. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Allon, Yoram; Cullen, Del; Patterson, Hannah (2000). The Wallflower Critical Guide to Contemporary North American Directors. Wallflower. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-903364-09-3.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen. Entertainment Weekly, January 17, 2015, "Glengarry Glen Ross".

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. rogerebert.com, October 2, 1992, "Glengarry Glen Ross". Accessed April 26, 2015.

- 1 2 Artisan Entertainment quoted at Metacritic, "Glengarry Glen Ross". Accessed April 26, 2015.

- ↑ Bernstein, Richard (August 15, 1991). "Despite the Odds, 'Glengarry' Is Being Filmed". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ↑ According to Ed Harris, while being interviewed on Inside the Actors Studio. Season 7. Episode 6. 2000-12-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weinraub, Bernard (October 12, 1992). "The Glengarry Math: Add Money and Stars, then Subtract Ego". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- 1 2 Blanchard, Jayne M (September 27, 1992). "Glengarry Hits the Screen with the Joys of Male Angst". Washington Times.

- ↑ Hartl, John (September 28, 1992). "Director is Happy to put Big Stars in Film Version of Mamet Play". Seattle Times.

- 1 2 3 4 "Glengarry Glen Ross Production Notes". New Line Cinema Press Kit. 1992.

- ↑ Berardinelli, James (2006). "Glengarry Glen Ross". ReelViews. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- 1 2 Powers, William F (October 4, 1992). "Pacino, Mamet and . . . Zupnik; Who? The Local Real Estate Mogul Behind Glengarry". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Clark, Jennifer (July 31, 1992). "Three U.S. entries sign on at 49th Venice Fest". Variety.

- ↑ Adilman, Sid (September 1, 1992). "Festivals scrap over movie". Toronto Star.

- ↑ "Glengarry Glen Ross". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (October 9, 1992). "Pros and Cons". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (October 2, 1992). "Glengarry Glen Ross". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Kroll, Jack (October 5, 1992). "Heels, Heroes and Hustlers". Newsweek. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (September 30, 1992). "Mamet's Real Estate Sharks and Their Prey". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (October 12, 1992). "Sweating Out Loud". Time. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ↑ Howe, Desson (October 2, 1992). "Glengarry Glen Ross". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Mandell, Zack (January 8, 2014). "Netflix Movie Month: "Glengarry Glen Ross" Review". Movie Room Reviews. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "Howards End NBR's best film". Variety. December 17, 1992. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ↑ Benson, Jim (December 30, 1992). "Globes Nod to Men, Aladdin". Variety.

- ↑ Spillman, Susan (February 18, 1993). "Oscar's independent streak". USA Today.

- ↑ "500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ↑ Scully, Mike (2006). Commentary for "Realty Bites", in The Simpsons: The Complete Ninth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ↑ Greaney, Dan (2006). Commentary for "Realty Bites", in The Simpsons: The Complete Ninth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Glengarry Glen Ross (film) |

- Glengarry Glen Ross at the Internet Movie Database

- Glengarry Glen Ross at AllMovie

- Glengarry Glen Ross at Box Office Mojo

- Glengarry Glen Ross at Rotten Tomatoes

- Glengarry Glen Ross at Metacritic

- "Despite the Odds, Glengarry Is Being Filmed" - The New York Times article

- Full "Coffee's for closers" Monologue