Computer-generated imagery

Computer-generated imagery (CGI) is the application of computer graphics to create or contribute to images in art, printed media, video games, films, television programs, shorts, commercials, videos, and simulators. The visual scenes may be dynamic or static and may be two-dimensional (2D), though the term "CGI" is most commonly used to refer to 3D computer graphics used for creating scenes or special effects in films and television. Additionally, the use of 2D CGI is often mistakenly referred to as "traditional animation", most often in the case when dedicated animation software such as Adobe Flash or Toon Boom is not used or the CGI is hand drawn using a tablet and mouse.

The term 'CGI animation' refers to dynamic CGI rendered as a movie. The term virtual world refers to agent-based, interactive environments. Computer graphics software is used to make computer-generated imagery for films, etc. Availability of CGI software and increased computer speeds have allowed individual artists and small companies to produce professional-grade films, games, and fine art from their home computers. This has brought about an Internet subculture with its own set of global celebrities, clichés, and technical vocabulary. The evolution of CGI led to the emergence of virtual cinematography in the 1990s where runs of the simulated camera are not constrained by the laws of physics.

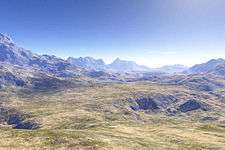

Static images and landscapes

Not only do animated images form part of computer-generated imagery, natural looking landscapes (such as fractal landscapes) are also generated via computer algorithms. A simple way to generate fractal surfaces is to use an extension of the triangular mesh method, relying on the construction of some special case of a de Rham curve, e.g. midpoint displacement.[1] For instance, the algorithm may start with a large triangle, then recursively zoom in by dividing it into four smaller Sierpinski triangles, then interpolate the height of each point from its nearest neighbors.[1] The creation of a Brownian surface may be achieved not only by adding noise as new nodes are created but by adding additional noise at multiple levels of the mesh.[1] Thus a topographical map with varying levels of height can be created using relatively straightforward fractal algorithms. Some typical, easy-to-program fractals used in CGI are the plasma fractal and the more dramatic fault fractal.[2]

A large number of specific techniques have been researched and developed to produce highly focused computer-generated effects — e.g. the use of specific models to represent the chemical weathering of stones to model erosion and produce an "aged appearance" for a given stone-based surface.[3]

Architectural scenes

Modern architects use services from computer graphic firms to create 3-dimensional models for both customers and builders. These computer generated models can be more accurate than traditional drawings. Architectural animation (which provides animated movies of buildings, rather than interactive images) can also be used to see the possible relationship a building will have in relation to the environment and its surrounding buildings. The rendering of architectural spaces without the use of paper and pencil tools is now a widely accepted practice with a number of computer-assisted architectural design systems.[4]

Architectural modeling tools allow an architect to visualize a space and perform "walk-throughs" in an interactive manner, thus providing "interactive environments" both at the urban and building levels.[5] Specific applications in architecture not only include the specification of building structures (such as walls and windows) and walk-throughs but the effects of light and how sunlight will affect a specific design at different times of the day.[6]

Architectural modeling tools have now become increasingly internet-based. However, the quality of internet-based systems still lags behind those of sophisticated in-house modeling systems.[7]

In some applications, computer-generated images are used to "reverse engineer" historical buildings. For instance, a computer-generated reconstruction of the monastery at Georgenthal in Germany was derived from the ruins of the monastery, yet provides the viewer with a "look and feel" of what the building would have looked like in its day.[8]

Anatomical models

Computer generated models used in skeletal animation are not always anatomically correct. However, organizations such as the Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute have developed anatomically correct computer-based models. Computer generated anatomical models can be used both for instructional and operational purposes. To date, a large body of artist produced medical images continue to be used by medical students, such as images by Frank Netter, e.g. Cardiac images. However, a number of online anatomical models are becoming available.

A single patient X-ray is not a computer generated image, even if digitized. However, in applications which involve CT scans a three-dimensional model is automatically produced from a large number of single slice x-rays, producing "computer generated image". Applications involving magnetic resonance imaging also bring together a number of "snapshots" (in this case via magnetic pulses) to produce a composite, internal image.

In modern medical applications, patient-specific models are constructed in 'computer assisted surgery'. For instance, in total knee replacement, the construction of a detailed patient-specific model can be used to carefully plan the surgery.[9] These three-dimensional models are usually extracted from multiple CT scans of the appropriate parts of the patient's own anatomy. Such models can also be used for planning aortic valve implantations, one of the common procedures for treating heart disease. Given that the shape, diameter, and position of the coronary openings can vary greatly from patient to patient, the extraction (from CT scans) of a model that closely resembles a patient's valve anatomy can be highly beneficial in planning the procedure.[10]

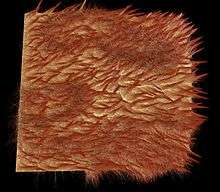

Generating cloth and skin images

Models of cloth generally fall into three groups:

- The geometric-mechanical structure at yarn crossing

- The mechanics of continuous elastic sheets

- The geometric macroscopic features of cloth.[11]

To date, making the clothing of a digital character automatically fold in a natural way remains a challenge for many animators.[12]

In addition to their use in film, advertising and other modes of public display, computer generated images of clothing are now routinely used by top fashion design firms.[13]

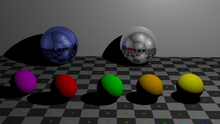

The challenge in rendering human skin images involves three levels of realism:

- Photo realism in resembling real skin at the static level

- Physical realism in resembling its movements

- Function realism in resembling its response to actions.[14]

The finest visible features such as fine wrinkles and skin pores are the size of about 100 µm or 0.1 millimetres. Skin can be modeled as a 7-dimensional bidirectional texture function (BTF) or a collection of bidirectional scattering distribution function (BSDF) over the target's surfaces.

Interactive simulation and visualization

Interactive visualization is a general term that applies to the rendering of data that may vary dynamically and allowing a user to view the data from multiple perspectives. The applications areas may vary significantly, ranging from the visualization of the flow patterns in fluid dynamics to specific computer aided design applications.[15] The data rendered may correspond to specific visual scenes that change as the user interacts with the system — e.g. simulators, such as flight simulators, make extensive use of CGI techniques for representing the world.[16]

At the abstract level, an interactive visualization process involves a "data pipeline" in which the raw data is managed and filtered to a form that makes it suitable for rendering. This is often called the "visualization data". The visualization data is then mapped to a "visualization representation" that can be fed to a rendering system. This is usually called a "renderable representation". This representation is then rendered as a displayable image.[16] As the user interacts with the system (e.g. by using joystick controls to change their position within the virtual world) the raw data is fed through the pipeline to create a new rendered image, often making real-time computational efficiency a key consideration in such applications.[16][17]

Computer animation

While computer generated images of landscapes may be static, the term computer animation only applies to dynamic images that resemble a movie. However, in general, the term computer animation refers to dynamic images that do not allow user interaction, and the term virtual world is used for the interactive animated environments.

Computer animation is essentially a digital successor to the art of stop motion animation of 3D models and frame-by-frame animation of 2D illustrations. Computer generated animations are more controllable than other more physically based processes, such as constructing miniatures for effects shots or hiring extras for crowd scenes, and because it allows the creation of images that would not be feasible using any other technology. It can also allow a single graphic artist to produce such content without the use of actors, expensive set pieces, or props.

To create the illusion of movement, an image is displayed on the computer screen and repeatedly replaced by a new image which is similar to the previous image, but advanced slightly in the time domain (usually at a rate of 24 or 30 frames/second). This technique is identical to how the illusion of movement is achieved with television and motion pictures.

Virtual worlds

A virtual world is a simulated environment, which allows the user to interact with animated characters, or interact with other users through the use of animated characters known as avatars. Virtual worlds are intended for its users to inhabit and interact, and the term today has become largely synonymous with interactive 3D virtual environments, where the users take the form of avatars visible to others graphically.[18] These avatars are usually depicted as textual, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional graphical representations, although other forms are possible[19] (auditory[20] and touch sensations for example). Some, but not all, virtual worlds allow for multiple users.

In courtrooms

Computer-generated imagery has been used in courtrooms, primarily since the early 2000s. However, some experts have argued that it is prejudicial. They are used to help judges or the jury to better visualize the sequence of events, evidence or hypothesis.[21] However, a 1997 study showed that people are poor intuitive physicists and easily influenced by computer generated images.[22] Thus it is important that jurors and other legal decision-makers be made aware that such exhibits are merely a representation of one potential sequence of events.

See also

- 3D modeling

- Anime Studio

- Animation database

- List of computer-animated films

- Blender (software) - DIY CGI

- Digital image

- Parallel rendering

- Photoshop is the industry standard commercial digital photo editing tool. Its FLOSS counterpart is GIMP.

- Poser DIY CGI optimized for soft models

- Ray tracing (graphics)

- Real-time computer graphics

- Shader

- Virtual human

- Virtual Physiological Human

- Maya, 3ds Max, Cinema4D, E-on Vue, Poser, and Blender are popular software packages that allow 3D modeling and CGI creation - see also the list of 3D computer graphics software.

References

- 1 2 3 Chaos and fractals: new frontiers of science by Heinz-Otto Peitgen, Hartmut Jürgens, Dietmar Saupe 2004 ISBN 0-387-20229-3 page 462-466

- ↑ Game programming gems 2 by Mark A. DeLoura 2001 ISBN 1-58450-054-9 page 240

- ↑ Digital modeling of material appearance by Julie Dorsey, Holly E. Rushmeier, François X. Sillion 2007 ISBN 0-12-221181-2 page 217

- ↑ Light Shadow Space: Architectural Rendering with Cinema 4D by Horst Sondermann 2008 ISBN 3-211-48761-1 pages 8-15

- ↑ Interactive environments with open-source software: 3D walkthroughs by Wolfgang Höhl, Wolfgang Höhl 2008 ISBN 3-211-79169-8 pages 24-29

- ↑ Advances in Computer and Information Sciences and Engineering by Tarek Sobh 2008 ISBN 1-4020-8740-3 pages 136-139

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Multimedia Technology and Networking, Volume 1 by Margherita Pagani 2005 ISBN 1-59140-561-0 page 1027

- ↑ Interactive storytelling: First Joint International Conference by Ulrike Spierling, Nicolas Szilas 2008 ISBN 3-540-89424-1 pages 114-118

- ↑ Total Knee Arthroplasty by Johan Bellemans, Michael D. Ries, Jan M.K. Victor 2005 ISBN 3-540-20242-0 pages 241-245

- ↑ I. Waechter et al. Patient Specific Models for Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Implantation in Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention -- MICCAI 2010 edited by Tianzi Jiang, 2010 ISBN 3-642-15704-1 pages 526-560

- ↑ Cloth modeling and animation by Donald House, David E. Breen 2000 ISBN 1-56881-090-3 page 20

- ↑ Film and photography by Ian Graham 2003 ISBN 0-237-52626-3 page 21

- ↑ Designing clothes: culture and organization of the fashion industry by Veronica Manlow 2007 ISBN 0-7658-0398-4 page 213

- ↑ Handbook of Virtual Humans by Nadia Magnenat-Thalmann and Daniel Thalmann, 2004 ISBN 0-470-02316-3 pages 353-370

- ↑ Mathematical optimization in computer graphics and vision by Luiz Velho, Paulo Cezar Pinto Carvalho 2008 ISBN 0-12-715951-7 page 177

- 1 2 3 GPU-based interactive visualization techniques by Daniel Weiskopf 2006 ISBN 3-540-33262-6 pages 1-8

- ↑ Trends in interactive visualization by Elena van Zudilova-Seinstra, Tony Adriaansen, Robert Liere 2008 ISBN 1-84800-268-8 pages 1-7

- ↑ Cook, A.D. (2009). A case study of the manifestations and significance of social presence in a multi-user virtual environment. MEd Thesis. Available online

- ↑ Biocca & Levy 1995, pp. 40–44

- ↑ Begault 1994

- ↑ Computer-generated images influence trial results The Conversation, 31 October 2013

- ↑ Kassin, S. M. (1997). "Computer-animated Display and the Jury: Facilitative and Prejudicial Effects". Law and Human Behavior. 40 (3): 269–281. doi:10.1023/a:1024838715221.

External links

| Library resources about Computer-generated imagery |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Computer-generated imagery. |

- A Critical History of Computer Graphics and Animation – a course page at Ohio State University that includes all the course materials and extensive supplementary materials (videos, articles, links).

- CG101: A Computer Graphics Industry Reference ISBN 073570046X Unique and personal histories of early computer graphics production, plus a comprehensive foundation of the industry for all reading levels.

- F/X Gods, by Anne Thompson, Wired, February 2005.

- "History Gets A Computer Graphics Make-Over" Tayfun King, Click, BBC World News (2004-11-19)

- NIH Visible Human Gallery