Confederate Memorial (Wilmington, North Carolina)

For Altar and Home | |

Location in North Carolina | |

| Coordinates | 34°14′03.44″N 77°56′45.2″W / 34.2342889°N 77.945889°W |

|---|---|

| Location | Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Material | Bronze & Granite |

| Completion date | 1924 |

| Dedicated to | To The Soldiers Of The Confederacy |

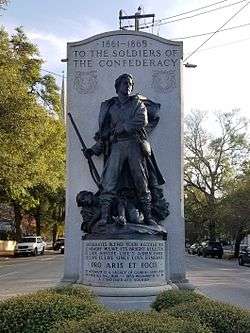

Located at the plaza of South Third and Dock Street in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina, the bronze and granite Confederate Memorial stands honoring Southern Soldiers who fought for The Confederacy.[1]

Description

The monument consists of an eleven-ton granite backdrop, granite base, and a bronze sculpture of one fallen and one standing soldier atop the base. The two soldiers represent the Confederacy, a confederation of 11 southern states which fought from 1861 - 1865 for independence from the United States during the American Civil War. The principal war aim of the Confederacy was to defend the right of 11 southern states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, & Tennessee) to secede from the Union and create a new nation, although it should be understood that this is one which relied heavily on a slave based economy and a deeply conservative and a social hierarchy based on both race and sex.[2][3]

Four of the eleven Southern States directly cited slavery or white supremacy as a reason for their secession. After 1 year, 8 months and 20 days of war, on January 1, 1863, US President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in rebelling states. As such, the principal war aim was shifted - after nearly two years - from either preserving the Union through Federal power, or defending the localized right to secede from it; to one which would now include the issue of American Slavery.[4]

This forced both sides to take definitive stances for or against the institution, within the borders of the states fighting for their independence and rebelling against Federal authority. Although the status of slaves in border states was somewhat ambiguous for a time, the lasting effects of emancipation did little to calm the reconstruction period when combined with the bitterness of post-war destruction in the South and the devastating loss of life.[5]

During the war, brutality meant that soldiers on both sides often felt geographically loyal, particularly to their homes and communities, in spite of controversial politics. As such, the war was the bloodiest in American History; and with contemporary estimates totaling over 620,000 dead; the war is believed to have killed more than every other American war, before or since, combined. A vast superiority of men and war materiel on the part of the Union left a lingering bitterness in Southern States (a good example might be the 45th NC infantry regiment, which began the war with 2,597 men, but surrendered with only 88 men and 7 officers), and a prevailing stereotype that white southerners, who had often given everything to the Confederate war effort, were unable to come to terms with their loss or accept the destruction and the social and economic changes that were imposed in the aftermath of the war.[6][7]

History

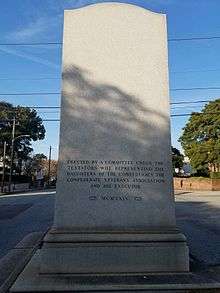

The United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization of female descendants of Confederate soldiers, had the Confederate Memorial erected in 1924 with a donation from Gabriel James Boney, whose name appears on the bottom of the statue. Additional donations were historically known locally to be commonplace among the widows, children, and close descendants of fallen Confederate soldiers and sailors, along with most of the townspeople. It has been argued that, instead of honoring the fallen exclusively, the erection of the monument functioned both as a form of protest against northerners who had flocked to the region, as well as a way to intimidate African Americans in the Jim Crow era, although both of these interpretations remain controversial.[8]

Henry Bacon who designed the Lincoln Memorial, George Davis Monument, and the Donald McRae House, is the architect also responsible for the design of the Confederate Memorial. Frank H. Packer who was the sculptor for the George Davis Monument, also sculpted the two bronze figures on the Confederate Memorial.[9] The creation and purpose of this monument was to honor Confederate beliefs.

An inscription along the top portion of the statue reads:

1861-1865

To the soldiers of the confederacy

The bottom portion of the statue reads:

Confederates blend your recollections

Let memory weave its bright reflections

Let love revive life's ashen embers

For love is life since love remembers

PRO ARIS ET FOCIS

This monument is a legacy of Gabriel James Boney

Born Wallace, NC 1846-Died Wilmington, NC 1915

A Confederate soldier[10]

The Latin words ‘Pro Aris Et Focis’ translates ‘For Altar and Home.’ This phrase was used by Southerners during and after the war to rationalize the contest as one upon which the survival of their nation was directly contingent. Wilmington and Fort Fisher, known as the 'Gibraltar of the Confederacy', made up one of only two major deepwater confederate ports that supplied the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and other Confederate field armies during the war. The Union Blockade of southern states meant that in order to receive food, weapons, and ammunition; the wartime populace and military of the south relied heavily on these fortified ports - Wilmington, NC and Charleston, SC, respectively - to keep the Confederacy alive.[11]

Contemporary southern attitude following the war stipulated that southern soldiers had fought to defend their homes and families from invading Federal field armies. The war in the south had resulted in Union troops burning Columbia, South Carolina; Richmond, Virginia; Jackson, Mississippi; and Atlanta, Georgia; laying siege to the town of Vicksburg, Mississippi; and shelling Charleston, South Carolina - in addition to attacking Fort Fisher near the city of Wilmington, North Carolina itself. These attitudes were compounded by deep family ties and fierce political loyalties on both sides and were especially strong in the bitter years of the Reconstruction period amid the legacy of destruction in the south. These were also deepened sharply through the deep social changes that came from the abolition of slavery, and its lasting effects for both southern whites and African Americans in the slaveholding states.[12]

Since being placed at the busy downtown intersection, the monument has had to undergo many repairs due to being hit by cars and cranes. In 1954, a car first knocked the statue down. In 1999, it was again hit by a car and knocked from its foundation and into the street. This caused a cracked foundation and the backdrop to be knocked over. While trying to reconstruct the monument, a crane carrying the backdrop slammed into a wall, cars, and power lines.[13] After an absence of almost a year and a half, the monument was repaired, restored, and replaced in 2000, only to be damaged again as it was being put back into place. The mishap was quickly fixed and remains complete today.

Nationally, local and state governments have begun removing Civil War monuments to Confederate war dead, or the Confederate cause generally, from public land—particularly in the wake of a collectively negative public attitude towards confederate symbols—despite regional defenses by family members, descendants, and many Southerners who have a deep reverence for what they see as the heroism of their forebears. Particularly as larger numbers of non-southerners have moved to the Wilmington area since the 1980s, the dynamics of the local population have facilitated a shifting public interpretation. This broad, national public frustration is a direct result of the adoption of Confederate symbols by, and their modern association with, various extremist groups and individuals, including hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.[14]

Sources

- ↑ Hutteman, Hewlett Ann. Postcard History Series: Wilmington, North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing 2000. 58.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (2003). Battle cry of freedom : the Civil War era ([New ed.]. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195168952.

- ↑ Potter, David M. (1996). The impending crisis : 1848-1861 ([Nachdr.]. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0061319297.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (1995). What they fought for, 1861-1865 (1st Anchor Books ed.). New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0385476348.

- ↑ Foner, Eric (2007). Reconstruction : America's unfinished revolution; 1863-1877 (1. Perennial classics ed., [Nachdr.]. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Perennial Classics. ISBN 978-0060937164.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (2003). Battle cry of freedom : the Civil War era ([New ed.]. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195168952.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (1995). What they fought for, 1861-1865 (1st Anchor Books ed.). New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0385476348.

- ↑ Hardy, Michael C. (2006). Remembering North Carolina's Confederates. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0738542973.

- ↑ Barbour, Clay. "Fallen Warrior." Wilmington Star News. 1999/03/01.

- ↑ Hutteman, Hewlett Ann. Postcard History Series: Wilmington, North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing 2000.

- ↑ "The Second Battle of Fort Fisher". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Foner, Eric (2007). Reconstruction : America's unfinished revolution; 1863-1877 (1. Perennial classics ed., [Nachdr.]. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Perennial Classics. ISBN 978-0060937164.

- ↑ Reiss, Cory. "Monumental Repairs." Wilmington Star News. 1999/11/04. 1A.

- ↑ Post, Washington. "Tug-of-war over Confederate monuments rages on". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 22 June 2016.