Crag martin

| Crag martin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dusky crag martin on nest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Hirundinidae |

| Subfamily: | Hirundininae |

| Genus: | Ptyonoprogne L. Reichenbach, 1850 |

| Species | |

| |

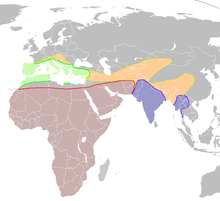

| P. rupestris resident year-round (Colours denote species limits, detailed ranges are on species' pages)P. rupestris breeding summer visitor P. concolor P. fuligula | |

The crag martins are four species of small passerine birds in the genus Ptyonoprogne of the swallow family. They are the Eurasian crag martin (P. rupestris), the pale crag martin (P. obsoleta), the rock martin (P. fuligula) and the dusky crag martin (P. concolor). They are closely related to each other, and have formerly sometimes been considered to be one species. They are closely related to the Hirundo barn swallows and are placed in that genus by some authorities. These are small swallows with brown upperparts, paler underparts without a breast band, and a square tail with white patches. They can be distinguished from each other on size, the colour shade of the upperparts and underparts, and minor plumage details like throat colour. They resemble the sand martin, but are darker below, and lack a breast band.

These are species of craggy mountainous habitats, although all three will also frequent human habitation. The African rock martin and the south Asian dusky crag martin are resident, but the Eurasian crag martin is a partial migrant; birds breeding in southern Europe are largely resident, but some northern breeders and most Asian birds are migratory, wintering in north Africa or India. They do not normally form large breeding colonies, but are more gregarious outside the breeding season. These martins build neat mud nests under cliff overhangs or in crevices in their mountain homes, and have readily adapted to the artificial cliffs provided by buildings and motorway bridges. Up to five eggs, white with dark blotches at the wider end, may be laid, and a second clutch is common. Ptyonoprogne martins feed mainly on insects caught in flight, and patrol cliffs near the breeding site with a slow hunting flight as they seek their prey. They may be hunted by falcons and infected with mites and fleas, but their large ranges and populations mean that none of the crag martins are considered to be threatened, and all are classed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

Taxonomy

The four Ptyonoprogne species are the Eurasian crag martin (P. rupestris) described as Hirundo rupestris by Italian naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 1769, the pale crag martin (P. obsoleta), described by Jean Cabanis in 1850, the rock martin (P. fuligula), described by German zoologist Martin Lichtenstein in 1842, and the dusky crag martin (P. concolor) formally described in 1832 as Hirundo concolor by British soldier and ornithologist William Henry Sykes. They were moved to the new genus Ptyonoprogne by German ornithologist Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach in 1850.[1] The genus name is derived from the Greek ptuon (φτυον), "a fan", referring to the shape of the opened tail, and Procne (Πρόκνη), a mythological girl who was turned into a swallow.[2]

These are members of the swallow family of birds, and are placed in the Hirundininae subfamily which comprises all swallows and martins except the very distinctive river martins. DNA sequence studies suggest that there are three major groupings within the Hirundininae, broadly correlating with the type of nest built.[3] The groups are the "core martins" including burrowing species like the sand martin, the "nest-adopters", which are birds like the tree swallow that utilise natural cavities, and the "mud nest builders". Ptyonoprogne species construct a mud nest and therefore belong to the latter group; They resemble the Hirundo species in that they make open cup nests, whereas Delichon martins build closed cups, and the Cecropis and Petrochelidon swallows, have retort-like closed nests with an entrance tunnel.[4] The genus Ptyonoprogne is closely related to the larger swallow genus Hirundo into which it is often subsumed, but a DNA analysis showed that a coherent enlarged Hirundo genus should contain all the mud-builder genera. Although the nests of the Ptyonoprogne crag martins resembles those of typical Hirundo species like the barn swallow, the DNA research showed that if the Delichon house martins are considered to be a separate genus, as is normally the case, Cecropis, Petrochelidon and Ptyonoprogne should also be split off.[3]

The small, pale northern subspecies of crag martin found in the mountains of North Africa and the Arabian peninsula is now usually split as the pale crag martin, Ptyonoprogne obsoleta.[5][6] The remaining birds are now identified as Eurasian crag martin.

Description

These martins are 12–15 cm (4.7–5.9 in) long with drab brown or grey plumage and a short square tail that has small white patches near the tips of all but the central and outermost pairs of feathers. The eyes are brown, the small bill is mainly black, and the legs are brownish-pink. The sexes are similar, but juveniles show pale edges to the upperparts and flight feathers. The species differ in plumage shades and size, Eurasian crag martin being significantly larger than the others. The flight is slow, with rapid wing beats interspersed with flat-winged glides.[5] The songs of these birds are simple twitterings, and contact calls include a high-pitched twee or chi, chi, and a tshir or trrt call like that of the house martin.[5][7]

These drab martins can only be confused with each other, or with sand martins of the genus Riparia. Even the smaller Ptyonoprogne species are slightly larger and more robust than the sand martin and brown-throated sand martin, and have the white tail spots which are absent from the Riparia martins.[8] Where the ranges of Ptyonoprogne species overlap, the Eurasian crag martin is darker, browner and 15% larger than the rock martin,[5][8] and larger and paler, particularly on its underparts, than the dusky crag martin.[9] The white tail spots of the Eurasian crag martin are significantly larger than those of both its relatives.[10] In the east of its range, the rock martin always has lighter, more contrasted underparts than the dusky crag martin.[5]

Distribution and habitat

These are exclusively Old World species. The rock martin breeds throughout Africa and through the Middle East as far as Afghanistan and Pakistan, and is replaced by the dusky crag martin further east in India and Indochina. The Eurasian crag martin breeds from Iberia and northwesternmost Africa through southern Europe, the Persian Gulf and the Himalayas to southwestern and northeastern China. Northern populations of the Eurasian crag martin are migratory, with European birds wintering in north Africa, Senegal, Ethiopia and the Nile Valley, and Asian breeders going to southern China, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East.[11] Some European birds stay north of the Mediterranean, and, like populations in warmer areas such as India, Turkey and Cyprus, just move to lower ground after breeding. The dusky crag martin and rock are largely resident apart from local movements after breeding, when many birds descend to lower altitudes,[5] although some pale northern rock martins from North African and southern Arabian may winter further south alongside the local subspecies in Ethiopia, Mali and Mauritania.[12]

The crag martins mainly breed on dry, warm and sheltered cliffs in mountainous areas with crags and gorges, and the Eurasian crag martin reaches 5,000 m (16,500 ft) in Central Asia. The use of buildings as artificial cliffs has enabled breeding expansion into lowland areas, particularly for the two tropical species,[5] and the rock martin breeds in desert towns.[13] In South Asia, migrant Eurasian birds sometimes join with flocks of the dusky crag martin and roost communally on ledges of cliffs or buildings in winter.[14]

Behaviour

Breeding

Martin pairs often nest alone, although where suitable sites are available small loose colonies may form. These are more common south of the Sahara, where up to 40 rock martin pairs together have been recorded. Crag martins aggressively defend their nesting territory against conspecifics and other species. The nest, built by both adults over several weeks, is made from several hundred mud pellets and lined with soft dry grass or sometimes feathers. It may be a half-cup when constructed under an overhang on a vertical wall or cliff, or shaped as a bowl like that of the barn swallow when placed on a sheltered ledge. The nest may be built on a rock cliff face, in a crevice or on a man-made structure, and is re-used for the second brood and in subsequent years. Usually two broods are raised, and the rock martin may nest for a third time in a season.[5]

The clutch is two to five eggs that are white with brownish, ruddy or grey blotches particularly at the wide end. The egg size ranges from an average 20.2 x 14.0 mm (0.80 x 0.55 in) with a weight of 2.08 g (0.073 oz) for the Eurasian crag martin to 17.7 x 13.0 mm (0.70 x 0.51 in) with a weight of 1.57 g (0.06 oz) for the dusky crag martin. Both adults incubate the eggs for 13–19 days to hatching, and feed the chicks at least ten times an hour until they fledge 24–27 days later. The fledged young continue to be fed by the parents for some time after they can fly.[5]

Feeding

Ptyonoprogne martins feed mainly on insects caught in flight, although they will occasionally feed on the ground. When breeding, birds often fly back and forth along a rock face catching insects in their bills and usually feeding close to the nesting territory. To maintain the high frequency with which the young are fed, the adults mainly forage in the best hunting zones in the immediate vicinity of the nest, since the further they have to fly to catch insects, the longer it would take to bring food to the chicks in the nest.[15] At other times, they may hunt low over open ground. The insects taken depend on what is locally available, but may include mosquitoes and other flies, aerial spiders, ants and beetles. Martins often feed alone, but sizeable groups may congregate if food is abundant, such as where insects are fleeing grass fires. The Eurasian crag martin may take aquatic species such as stoneflies, caddisflies and pond skaters.[5] Cliff faces generate standing waves in the airflow which concentrate insects near vertical areas. Crag martins exploit the area close to the cliff when they hunt, relying on their high manoeuvrability and ability to perform tight turns.[15]

Predators and parasites

The crag martins may be hunted by fast, agile birds of prey such as the African hobby or Eurasian hobby that specialise in catching swallows and martins in flight,[16] and by other falcons such as the peregrine and Taita falcons.[17][18][19] Crows may attack migrating Eurasian crag martins,[11] and that species also treats common kestrels, Eurasian sparrowhawks, Eurasian jays and common ravens as predators if they approach the nesting cliffs.[15] The dusky crag martin has been recorded in the diet of the greater false vampire bat, Megaderma lyra.[20]

Crag martins may host parasites, including blood-sucking mites of the genus Dermanyssus such as D. chelidonis,[21] and the nasal mite Ptilonyssus ptyonoprognes.[22] Invertebrate species first found in nests of crag martin species include the tick Argas (A.) africolumbae from a rock martin nest[23] and the fly Ornithomya rupes and the flea Ceratophyllus nanshanensis from European crag martin nests.[24][25]

Status

All four species have extensive ranges and large populations, and the increasing use of artificial nest sites has enabled range expansion. The rock martin often breeds in lowland and desert towns,[26] the Eurasian crag martin's range is expanding in Austria, Switzerland, the former Yugoslavia, Romania, and Bulgaria,[5][8] and the dusky crag martin is spreading northeastwards into Guangxi,[27] south into lowland Laos,[28] and westwards to the hills and plains of Sindh.[29] There is also a recent unconfirmed report from Cambodia.[30] Their large ranges and presumed high numbers mean that none of the crag martins are considered to be threatened, and all are classed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[31][32]

References

- ↑ Reichenbach (1850) plate LXXXVII figure 6.

- ↑ "Crag Martin Ptyonoprogne rupestris [Scopoli, 1769]". Bird facts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- 1 2 Sheldon, Frederick H; Whittingham, Linda A; Moyle, Robert G; Slikas, Beth; Winkler, David W (2005). "Phylogeny of swallows (Aves: Hirundinidae) estimated from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA". Molecular phylogenetics and evolution. 35 (1): 254–270. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.008. PMID 15737595.

- ↑ Winkler, David W; Sheldon, Frederick H (1993). "Evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae): A molecular phylogenetic perspective" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 90 (12): 5705–5707. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5705. PMC 46790

. PMID 8516319. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

. PMID 8516319. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Turner (1989) pp. 158–164

- ↑ Bergier, Patrick (2007). "L'Hirondelle isabelline Ptyonoprogne fuligula au Maroc" (PDF). Go-South Bulletin (in French). 4: 6–25.

- ↑ Mullarney et al (1999) p.240

- 1 2 3 Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1059–1061

- ↑ Grimmett et al (2002) p. 268

- ↑ Rasmussen & Anderton (2005) p. 311

- 1 2 Dodsworth, P T L (1912). "The Crag Martin (Ptyonoprogne rupestris)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 21 (2): 660–661.

- ↑ Barlow et al. (1997) pp. 276–277

- ↑ Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1058–1059

- ↑ Ali & Ripley (1986) pp. 53–54

- 1 2 3 Fantur, von Roman (1997). "Die Jagdstrategie der Felsenschwalbe (Hirundo rupestris) [The hunting strategy of the crag martin]" (PDF). Carinthia (in German and English). 187 (107): 229–252.

- ↑ Barlow et al. (1997) p. 165

- ↑ Rizzolli, Franco; Sergio, Fabrizio; Marchesi, Luigi; Pedrini, Paolo (2005). "Density, productivity, diet and population status of the Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus in the Italian Alps". Bird Study. 52 (2): 188–192. doi:10.1080/00063650509461390.

- ↑ Simmons, Robert E; Jenkins, Andrew R; Brown Christopher J "A review of the population status and threats to Peregrine Falcons throughout Namibia" in Sielicki & Mizera (2008) pp. 99–108

- ↑ Dowsett, R J; Douglas, M G; Stead, D E; Taylor, V A; Alder, J R; Carter, A T (July 1983). "Breeding and other observations on the Taita Falcon Falco fasciinucha". Ibis. 125 (3): 362–366. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1979.tb05020.x.

- ↑ "Megaderma lyra". Bats in China. The Darwin Initiative Centre for Bat Research. Retrieved 6 April 2010

- ↑ Roy, Lise; Chauve, C M (2007). "Historical review of the genus Dermanyssus Dugès, 1834 (Acari: Mesostigmata: Dermanyssidae)" (PDF). Parasite. 14 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1051/parasite/2007142087. PMID 17645179.

- ↑ Amrine, Jim. "Bibliography of the Eriophyidae". Biology Catalog. Texas A&M University Department of Entomology. Retrieved 30 March 2010

- ↑ Hoogstraal, Harry; Kaiser, Makram N; Walker, Jane B; Ledger, John A; Converse, James D; Rice, Robin G A (June 1975). "Observations on the subgenus Argas (Ixodoidea: Argasidae: Argas) 10. A. (A.) africolumbae, n. sp., a Pretoria virus-infected parasite of birds in southern and eastern Africa". Journal of Medical Entomology. 12 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1093/jmedent/12.2.194.

- ↑ Hutson, A M (1981). "A new species of the Ornithomya biloba-group (Dipt., Hippoboscidae) from crag martin (Ptyonoprogne rupestris) (Aves, Hirundinidae)". Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft. 54 (1–2): 157–162.

- ↑ Tsai, L-y; Pan, F-c; Liu Chuan (1980). "A new species of Ceratophyllus from Chinghai Province, China". Acta Entomologica Sinica. 23 (1): 79–81.

- ↑ "Species factsheet Hirundo fuligula ". BirdLife International. Retrieved 11 April 2010

- ↑ Evans, T D; Towll, H C; Timmins, R J; Thewlis, R M; Stones, A J; Robichaud, W G; Barzen J (2000). "Ornithological records from the lowlands of southern Laos during December 1995-September 1996, including areas on the Thai and Cambodian borders" (PDF). Forktail. 16: 29–52.

- ↑ Shing, Lee Kwok; Wai-neng Lau, Michael; Fellowes, John R; Lok, Chan Bosco Pui (2006). "Forest bird fauna of South China: notes on current distribution and status" (PDF). Forktail. 22: 23–38.

- ↑ Azam, Mirza Mohammad; Shafique, Chaudhry M (2005). "Birdlife in Nagarparkar, district Tharparkar, Sindh" (PDF). Records Zoological Survey of Pakistan. 16: 26–32.

- ↑ Eaton, James. "Cambodia Oriental Bird Club fundraising tour 21st January – 2nd February 2007" (PDF). birdtourasia. Retrieved 7 April 2010

- ↑ "Species factsheet Hirundo rupestris". BirdLife International. Retrieved 26 March 2010

- ↑ "Species factsheet Hirundo concolor". BirdLife International. Retrieved 4 April 2010

Cited texts

- Ali, Salim; Ripley, Sidney Dillon (1986). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 5 (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561857-2.

- Grimmett, Richard; Inskipp, Carol; Inskipp, Tim (2002). Birds of India. London: Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd. p. 226. ISBN 0-7136-6304-9.

- Hume, Allan Octavian (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian birds. 2 (2 ed.). London: R H Porter.

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-219728-6.

- Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-66-0.

- Reichenbach, Heinrich Gustav (1850). Avium systema naturale. (in German). Dresden and Leipzig: F. Hofmeister.

- Scopoli, Giovanni Antonio (1769). Annus I Historico-Naturalis (in French). Lipsiae: Christian Gottlob Hischeri.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- Turner, Angela K; Rose, Chris (1989). A handbook to the swallows and martins of the world. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7470-3202-5.