Supreme Court of the United States

| Supreme Court of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | September 24, 1789 |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°WCoordinates: 38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W |

| Composition method | Presidential nomination with Senate confirmation |

| Authorized by | United States Constitution |

| Judge term length | Life tenure |

| Number of positions | 9, by statute |

| Website |

www |

| Chief Justice of the United States | |

| Currently | John Roberts |

| Since | September 29, 2005 |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Legislature

|

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest federal court of the United States. Established pursuant to Article III of the United States Constitution in 1789, it has ultimate (and largely discretionary) appellate jurisdiction over all federal courts and over state court cases involving issues of federal law, plus original jurisdiction over a small range of cases. In the legal system of the United States, the Supreme Court is the final interpreter of federal constitutional law, although it may only act within the context of a case in which it has jurisdiction.

The Court normally consists of the Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices who are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Once appointed, justices have life tenure unless they resign, retire, or are removed after impeachment (though no justice has ever been removed). In modern discourse, the justices are often categorized as having conservative, moderate, or liberal philosophies of law and of judicial interpretation. Each justice has one vote, and while many cases are decided unanimously, the highest profile cases often expose ideological beliefs that track with those philosophical or political categories. The Court meets in the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C.

The Supreme Court is sometimes colloquially referred to as SCOTUS, in analogy to other acronyms such as POTUS.[1]

History

The ratification of the United States Constitution established the Supreme Court in 1789. Its powers are detailed in Article Three of the Constitution. The Supreme Court is the only court specifically established by the Constitution, and all the others were created by Congress. Congress is also responsible for conferring the title "justice" upon the associate justices, who have been known to scold lawyers for instead using the term "judge", which is the term used by the Constitution.[2]

The Court first convened on February 2, 1790,[3] by which time five of its six initial positions had been filled. According to historian Fergus Bordewich, in its first session: "[T]he Supreme Court convened for the first time at the Royal Exchange Building on Broad Street, a few steps from Federal Hall. Symbolically, the moment was pregnant with promise for the republic, this birth of a new national institution whose future power, admittedly, still existed only in the mind's eye of a few farsighted Americans. Impressively bewigged and swathed in their robes of office, Chief Justice Jay and three associate justices— William Cushing of Massachusetts, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, and John Blair of Virginia— sat augustly before a throng of spectators and waited for something to happen. Nothing did. They had no cases to consider. After a week of inactivity, they adjourned until September, and everyone went home."[4]

The sixth member (James Iredell) was not confirmed until May 12, 1790. Because the full Court had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two).[5] However, Congress has always allowed less than the Court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a quorum of four judges in 1789.[6]

Earliest beginnings to Marshall

Under Chief Justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the Court heard few cases; its first decision was West v. Barnes (1791), a case involving a procedural issue.[7] The Court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige,[8] a situation not helped by the highest-profile case of the era, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), which was reversed within two years by the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment.[9]

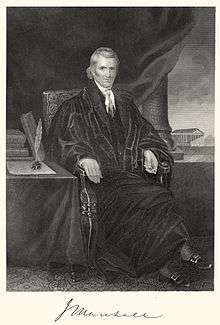

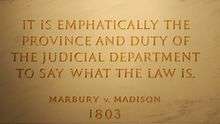

The Court's power and prestige grew substantially during the Marshall Court (1801–35).[10] Under Marshall, the Court established the power of judicial review over acts of Congress,[11] including specifying itself as the supreme expositor of the Constitution (Marbury v. Madison)[12][13] and made several important constitutional rulings giving shape and substance to the balance of power between the federal government and the states (prominently, Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, McCulloch v. Maryland and Gibbons v. Ogden).[14][15][16][17]

The Marshall Court also ended the practice of each justice issuing his opinion seriatim,[18] a remnant of British tradition,[19] and instead issuing a single majority opinion.[18] Also during Marshall's tenure, although beyond the Court's control, the impeachment and acquittal of Justice Samuel Chase in 1804–05 helped cement the principle of judicial independence.[20][21]

From Taney to Taft

The Taney Court (1836–64) made several important rulings, such as Sheldon v. Sill, which held that while Congress may not limit the subjects the Supreme Court may hear, it may limit the jurisdiction of the lower federal courts to prevent them from hearing cases dealing with certain subjects.[22] Nevertheless, it is primarily remembered for its ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford,[23] which helped precipitate the Civil War.[24] In the Reconstruction era, the Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910) interpreted the new Civil War amendments to the Constitution[17] and developed the doctrine of substantive due process (Lochner v. New York;[25] Adair v. United States).[26]

Under the White and Taft Courts (1910–30), the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment had incorporated some guarantees of the Bill of Rights against the states (Gitlow v. New York),[27] grappled with the new antitrust statutes (Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States), upheld the constitutionality of military conscription (Selective Draft Law Cases)[28] and brought the substantive due process doctrine to its first apogee (Adkins v. Children's Hospital).[29]

The New Deal era

During the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson Courts (1930–53), the Court gained its own accommodation in 1935[30] and changed its interpretation of the Constitution, giving a broader reading to the powers of the federal government to facilitate President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal (most prominently West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn, United States v. Darby and United States v. Butler).[31][32][33] During World War II, the Court continued to favor government power, upholding the internment of Japanese citizens (Korematsu v. United States) and the mandatory pledge of allegiance (Minersville School District v. Gobitis). Nevertheless, Gobitis was soon repudiated (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette), and the Steel Seizure Case restricted the pro-government trend.

Warren and Burger

The Warren Court (1953–69) dramatically expanded the force of Constitutional civil liberties.[34] It held that segregation in public schools violates equal protection (Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling v. Sharpe and Green v. County School Bd.)[35] and that traditional legislative district boundaries violated the right to vote (Reynolds v. Sims). It created a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut),[36] limited the role of religion in public school (most prominently Engel v. Vitale and Abington School District v. Schempp),[37][38] incorporated most guarantees of the Bill of Rights against the States—prominently Mapp v. Ohio (the exclusionary rule) and Gideon v. Wainwright (right to appointed counsel),[39][40]—and required that criminal suspects be apprised of all these rights by police (Miranda v. Arizona);[41] At the same time, however, the Court limited defamation suits by public figures (New York Times v. Sullivan) and supplied the government with an unbroken run of antitrust victories.[42]

The Burger Court (1969–86) marked a conservative shift.[43] It also expanded Griswold's right to privacy to strike down abortion laws (Roe v. Wade),[44] but divided deeply on affirmative action (Regents of the University of California v. Bakke)[45] and campaign finance regulation (Buckley v. Valeo),[46] and dithered on the death penalty, ruling first that most applications were defective (Furman v. Georgia),[47] then that the death penalty itself was not unconstitutional (Gregg v. Georgia).[47][48][49]

Rehnquist and Roberts

The Rehnquist Court (1986–2005) was noted for its revival of judicial enforcement of federalism,[50] emphasizing the limits of the Constitution's affirmative grants of power (United States v. Lopez) and the force of its restrictions on those powers (Seminole Tribe v. Florida, City of Boerne v. Flores).[51][52][53][54][55] It struck down single-sex state schools as a violation of equal protection (United States v. Virginia), laws against sodomy as violations of substantive due process (Lawrence v. Texas),[56] and the line item veto (Clinton v. New York), but upheld school vouchers (Zelman v. Simmons-Harris) and reaffirmed Roe's restrictions on abortion laws (Planned Parenthood v. Casey).[57] The Court's decision in Bush v. Gore, which ended the electoral recount during the presidential election of 2000, was controversial.[58][59]

The Roberts Court (2005–present) is regarded by some as more conservative than the Rehnquist Court.[60][61] Some of its major rulings have concerned federal preemption (Wyeth v. Levine), civil procedure (Twombly-Iqbal), abortion (Gonzales v. Carhart),[62] climate change (Massachusetts v. EPA), same-sex marriage (United States v. Windsor and Obergefell v. Hodges), and the Bill of Rights, prominently Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (First Amendment),[63] Heller-McDonald (Second Amendment),[64] and Baze v. Rees (Eighth Amendment).[65][66]

Composition

Size of the Court

Article III of the United States Constitution does not specify the number of justices. The Judiciary Act of 1789 called for the appointment of six justices, and as the nation's boundaries grew, Congress added justices to correspond with the growing number of judicial circuits: seven in 1807, nine in 1837, and ten in 1863.

In 1866, at the behest of Chief Justice Chase, Congress passed an act providing that the next three justices to retire would not be replaced, which would thin the bench to seven justices by attrition. Consequently, one seat was removed in 1866 and a second in 1867. In 1869, however, the Circuit Judges Act returned the number of justices to nine,[67] where it has since remained.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to expand the Court in 1937. His proposal envisioned appointment of one additional justice for each incumbent justice who reached the age of 70 years 6 months and refused retirement, up to a maximum bench of 15 justices. The proposal was ostensibly to ease the burden of the docket on elderly judges, but the actual purpose was widely understood as an effort to pack the Court with justices who would support Roosevelt's New Deal.[68] The plan, usually called the "Court-packing Plan", failed in Congress.[69] Nevertheless, the Court's balance began to shift within months when Justice van Devanter retired and was replaced by Senator Hugo Black. By the end of 1941, Roosevelt had appointed seven justices and elevated Harlan Fiske Stone to Chief Justice.[70]

Appointment and confirmation

The U.S. Constitution states that the President "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Judges of the Supreme Court."[71] Most presidents nominate candidates who broadly share their ideological views, although a justice's decisions may end up being contrary to a president's expectations. Because the Constitution sets no qualifications for service as a justice, a president may nominate anyone to serve, subject to Senate confirmation.

In modern times, the confirmation process has attracted considerable attention from the press and advocacy groups, which lobby senators to confirm or to reject a nominee depending on whether their track record aligns with the group's views. The Senate Judiciary Committee conducts hearings and votes on whether the nomination should go to the full Senate with a positive, negative or neutral report. The committee's practice of personally interviewing nominees is relatively recent. The first nominee to appear before the committee was Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925, who sought to quell concerns about his links to Wall Street, and the modern practice of questioning began with John Marshall Harlan II in 1955.[72] Once the committee reports out the nomination, the full Senate considers it. Rejections are relatively uncommon; the Senate has explicitly rejected twelve Supreme Court nominees, most recently Robert Bork in 1987.

Nevertheless, not every nominee has received a floor vote in the Senate. Although Senate rules do not necessarily allow a negative vote in committee to block a nomination, a nominee may be filibustered once debate has begun in the full Senate. No nomination for associate justice has ever been filibustered, but President Lyndon Johnson's nomination of sitting Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice was successfully filibustered in 1968. A president may also withdraw a nomination before the actual confirmation vote occurs, typically because it is clear that the Senate will reject the nominee, most recently Harriet Miers in 2006.

Once the Senate confirms a nomination, the president must prepare and sign a commission, to which the Seal of the Department of Justice must be affixed, before the new justice can take office.[73] The seniority of an associate justice is based on the commissioning date, not the confirmation or swearing-in date.[74]

Before 1981, the approval process of justices was usually rapid. From the Truman through Nixon administrations, justices were typically approved within one month. From the Reagan administration to the present, however, the process has taken much longer. Some believe this is because Congress sees justices as playing a more political role than in the past.[75] According to the Congressional Research Service, the average number of days from nomination to final Senate vote since 1975 is 67 days (2.2 months), while the median is 71 days (or 2.3 months).[76][77]

Recess appointments

When the Senate is in recess, a president may make temporary appointments to fill vacancies. Recess appointees hold office only until the end of the next Senate session (less than two years). The Senate must confirm the nominee for them to continue serving; of the two chief justices and six associate justices who have received recess appointments, only Chief Justice John Rutledge was not subsequently confirmed.[78]

No president since Dwight D. Eisenhower has made a recess appointment to the Court, and the practice has become rare and controversial even in lower federal courts.[79] In 1960, after Eisenhower had made three such appointments, the Senate passed a "sense of the Senate" resolution that recess appointments to the Court should only be made in "unusual circumstances."[80] Such resolutions are not legally binding but are an expression of Congress's views in the hope of guiding executive action.[80][81]

Tenure

The Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior" (unless appointed during a Senate recess). The term "good behavior" is understood to mean justices may serve for the remainder of their lives, unless they are impeached and convicted by Congress, resign or retire.[82] Only one justice has been impeached by the House of Representatives (Samuel Chase, March 1804), but he was acquitted in the Senate (March 1805).[83] Moves to impeach sitting justices have occurred more recently (for example, William O. Douglas was the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970; and Abe Fortas resigned while hearings were being organized), but they did not reach a vote in the House. No mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign.[84]

Because justices have indefinite tenure, timing of vacancies can be unpredictable. Sometimes vacancies arise in quick succession, as in the early 1970s when Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. and William Rehnquist were nominated to replace Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II, who retired within a week of each other. Sometimes a great length of time passes between nominations, such as the eleven years between Stephen Breyer's nomination in 1994 to succeed Harry Blackmun and the nomination of John Roberts in 2005 to fill the seat of Sandra Day O'Connor (though Roberts' nomination was withdrawn and resubmitted for the role of Chief Justice after Rehnquist died).

Despite the variability, all but four presidents have been able to appoint at least one justice. William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, though his successor (John Tyler) made an appointment during that presidential term. Likewise, Zachary Taylor died early in his term, but his successor (Millard Fillmore) also made a Supreme Court nomination before the end of that term. Andrew Johnson, who became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was denied the opportunity to appoint a justice by a reduction in the size of the Court. Jimmy Carter is the only president to complete at least one term in office without making any appointments to the Court.

Three presidents have appointed justices who collectively served more than 100 years: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln.[85]

Membership

Current justices

The court currently has eight justices and one vacancy after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia on February 13, 2016.

Vacancy and pending nomination

| Seat | Seat last held by | Vacancy reason | Date of vacancy | Nominee | Date of nomination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Antonin Scalia | Death | February 13, 2016 [86] | Merrick Garland[87][88] | March 16, 2016 |

Court demographics

The Court currently has five men and three women justices. One justice is African American, one is Latina, and the remaining six are non-Hispanic white; five justices are Roman Catholics, and three are Jewish. The average age is 69 years, 9 months. Every current justice has an Ivy League background.[89] Four justices are from the state of New York, two from California, one from New Jersey, and one from Georgia.

In the 19th century, every justice was a man of European descent (usually Northern European), and almost always Protestant. Concerns about diversity focused on geography, to represent all regions of the country, rather than religious, ethnic, or gender diversity.[90]

Most justices have been Protestants, including 35 Episcopalians, 19 Presbyterians, 10 Unitarians, 5 Methodists, and 3 Baptists.[91][92] The first Catholic justice was Roger Taney in 1836, and 1916 saw the appointment of the first Jewish justice, Louis Brandeis. Several Catholic and Jewish justices have since been appointed, and in recent years the situation has reversed: after the retirement of Justice Stevens in 2010, the Court is without a Protestant for the first time.[93]

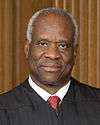

Racial, ethnic, and gender diversity began to increase in the late 20th century. Thurgood Marshall became the first African American justice in 1967. Sandra Day O'Connor became the first female justice in 1981. Antonin Scalia became the first Italian-American to serve on the Court in 1986. Marshall was succeeded by African American Clarence Thomas in 1991. O'Connor was joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993. After O'Connor's retirement Ginsburg was joined in 2009 by Sonia Sotomayor, the first Latina justice; and in 2010 by Elena Kagan, for a total of four female justices in the Court's history.

Retired justices

There are currently three living retired justices of the Supreme Court of the United States: John Paul Stevens, Sandra Day O'Connor, and David Souter. As retired justices, they no longer participate in the work of the Supreme Court, but may be designated for temporary assignments to sit on lower federal courts, usually the United States Courts of Appeals. Such assignments are formally made by the Chief Justice, on request of the Chief Judge of the lower court and with the consent of the retired Justice. In recent years, Justice O'Connor has sat with several Courts of Appeals around the country, and Justice Souter has frequently sat on the First Circuit, the court of which he was briefly a member before joining the Supreme Court.

The status of a retired Justice is analogous to that of a Circuit or District Judge who has taken senior status, and eligibility of a Supreme Court Justice to assume retired status (rather than simply resign from the bench) is governed by the same age and service criteria.

Justices sometimes strategically plan their decisions to leave the bench, with personal, institutional, and partisan factors playing a role.[94][95] The fear of mental decline and death often motivates justices to step down. The desire to maximize the Court's strength and legitimacy through one retirement at a time, when the Court is in recess, and during non-presidential election years suggests a concern for institutional health. Finally, especially in recent decades, many justices have timed their departure to coincide with a philosophically compatible president holding office, to ensure that a like-minded successor would be appointed.[96][97]

| Name | Born | Appt. by | Retired under | Conf. vote | Age at appt. | First day | Date of retirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

April 20, 1920 (age 96) in Chicago, Illinois |

Gerald Ford | Barack Obama | 98–0 | 55 | December 19, 1975 | June 29, 2010 |

|

March 26, 1930 (age 86) in El Paso, Texas |

Ronald Reagan | George W. Bush | 99–0 | 51 | September 25, 1981 | January 31, 2006 |

|

September 17, 1939 (age 77) in Melrose, Massachusetts |

George H. W. Bush | Barack Obama | 90–9 | 51 | October 9, 1990 | June 29, 2009 |

Seniority and seating

Many of the internal operations of the Court are organized by the seniority of the justices; the Chief Justice is considered the most senior member of the Court, regardless of the length of his or her service. The Associate Justices are then ranked by the length of their service.

During Court sessions, the justices sit according to seniority, with the Chief Justice in the center, and the Associate Justices on alternating sides, with the most senior Associate Justice on the Chief Justice's immediate right, and the most junior Associate Justice seated on the left farthest away from the Chief Justice. Therefore, the current court sits as follows from left to right, from the perspective of those facing the Court: Kagan, Alito, Ginsburg, Kennedy (most senior Associate Justice), Roberts (Chief Justice), Thomas, Breyer, Sotomayor. The final seat is reserved for the next appointee, who will be the most junior member. In the official yearly Court photograph, justices are arranged similarly, with the five most senior members sitting in the front row in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (The most recent photograph, prior to Scalia's death, included Thomas, Scalia, Roberts, Kennedy, Ginsburg), and the four most junior justices standing behind them, again in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (Sotomayor, Breyer, Alito, Kagan).

In the justices' private conferences, the current practice is for them to speak and vote in order of seniority from the Chief Justice first to the most junior Associate Justice last. The most junior Associate Justice in these conferences is charged with any menial tasks the justices may require as they convene alone, such as answering the door of their conference room, serving coffee, and transmitting the orders of the Court to the court's clerk.[98] Justice Joseph Story served the longest as the junior justice, from February 3, 1812, to September 1, 1823, for a total of 4,228 days. Justice Stephen Breyer follows close behind, with 4,199 days when Samuel Alito joined the court on January 31, 2006.[99]

Salary

For the years 2009 through 2012, associate justices were paid $213,900 and the chief justice $223,500.[100] Article III, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution prohibits Congress from reducing the pay for incumbent justices. Once a justice meets age and service requirements, the justice may retire. Judicial pensions are based on the normal formula for federal employees, but a justice's pension will never be less than their salary at time of retirement. (The same procedure applies to judges of other federal courts.)

Judicial leanings

Although justices are nominated by the President in power, justices do not represent or receive official endorsements from political parties, as is accepted practice in the legislative and executive branches. Jurists are, however, informally categorized in legal and political circles as being judicial conservatives, moderates, or liberals. Such leanings, however, generally refer to legal outlook rather than a political or legislative one. The nominations of justices are endorsed by individual politicians in the legislative branch who vote their approval or disapproval of the nominated justice.

Following the death of Antonin Scalia in February 2016, the Court consists of four justices appointed by Republican presidents and four appointed by Democratic presidents. It is popularly accepted that Chief Justice Roberts and justices Thomas and Alito (appointed by Republican presidents) comprise the Court's conservative wing. Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan (appointed by Democratic presidents) comprise the Court's liberal wing. Justice Kennedy (appointed by President Reagan) is generally considered "a conservative who has occasionally voted with liberals",[101] and up until Justice Scalia's death, was often the swing vote that determined the outcome of cases divided between the conservative and liberal wings.[102][103][104]

Tom Goldstein argued in an article in SCOTUSblog in 2010, that the popular view of the Supreme Court as sharply divided along ideological lines and each side pushing an agenda at every turn is "in significant part a caricature designed to fit certain preconceptions."[105] He pointed out that in the 2009 term, almost half the cases were decided unanimously, and only about 20% were decided by a 5-to-4 vote. Barely one in ten cases involved the narrow liberal/conservative divide (fewer if the cases where Sotomayor recused herself are not included). He also pointed to several cases that defied the popular conception of the ideological lines of the Court.[106] Goldstein further argued that the large number of pro-criminal-defendant summary dismissals (usually cases where the justices decide that the lower courts significantly misapplied precedent and reverse the case without briefing or argument) were an illustration that the conservative justices had not been aggressively ideological. Likewise, Goldstein stated that the critique that the liberal justices are more likely to invalidate acts of Congress, show inadequate deference to the political process, and be disrespectful of precedent, also lacked merit: Thomas has most often called for overruling prior precedent (even if long standing) that he views as having been wrongly decided, and during the 2009 term Scalia and Thomas voted most often to invalidate legislation.

According to statistics compiled by SCOTUSblog, in the twelve terms from 2000 to 2011, an average of 19 of the opinions on major issues (22%) were decided by a 5–4 vote, with an average of 70% of those split opinions decided by a Court divided along the traditionally perceived ideological lines (about 15% of all opinions issued). Over that period, the conservative bloc has been in the majority about 62% of the time that the Court has divided along ideological lines, which represents about 44% of all the 5–4 decisions.[107]

In the October 2010 term, the Court decided 86 cases, including 75 signed opinions and 5 summary reversals (where the Court reverses a lower court without arguments and without issuing an opinion on the case).[108][109] Four were decided with unsigned opinions, two cases affirmed by an equally divided Court, and two cases were dismissed as improvidently granted. Justice Kagan recused herself from 26 of the cases due to her prior role as United States Solicitor General. Of the 80 cases, 38 (about 48%, the highest percentage since the October 2005 term) were decided unanimously (9–0 or 8–0), and 16 decisions were made by a 5–4 vote (about 20%, compared to 18% in the October 2009 term, and 29% in the October 2008 term).[110] However, in fourteen of the sixteen 5–4 decisions, the Court divided along the traditional ideological lines (with Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan on the liberal side, and Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito on the conservative, and Kennedy providing the "swing vote"). This represents 87% of those 16 cases, the highest rate in the past 10 years. The conservative bloc, joined by Kennedy, formed the majority in 63% of the 5–4 decisions, the highest cohesion rate of that bloc in the Roberts court.[108][111][112][113][114]

In the October 2011 term, the Court decided 75 cases. Of these, 33 (about 44%) were decided unanimously, and 15 (about 20%, the same percentage as in the previous term) were decided by a vote of 5–4. Of the latter 15, the Court divided along the perceived ideological lines 10 times, with Justice Kennedy siding with the conservative justices (Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito) five times, and with the liberal justices (Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan) five times.[107][115][116]

In the October 2012 term, the Court decided 78 cases. Five of them were decided in unsigned opinions. 38 out of the 78 decisions (representing 49% of the decisions) were unanimous in judgement, with 24 decisions being completely unanimous (a single opinion with every justice that participated joining it). This was the largest percentage of unanimous decisions that the Court had in ten years, since the October 2002 term (when 51% of the decisions handed down were unanimous). The Court split 5-4 in 23 cases (29% of the total); of these, 16 broke down along the traditionally perceived ideological lines, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito on one side, Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan on the other, and Justice Kennedy holding the balance. Of these 16 cases, Justice Kennedy sided with the conservatives on 10 cases, and with the liberals on 6. Three cases were decided by an interesting alignment of justices, with Chief Justice Roberts joined by Justices Kennedy, Thomas, Breyer and Alito in the majority, with Justices Scalia, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan in the minority. The greatest agreement between justices was between Ginsburg and Kagan, who agreed on 72 of the 75 cases in which both voted; the lowest agreement between justices was between Ginsburg and Alito, who agreed only on 45 out of 77 cases in which they both participated. Justice Kennedy was in the majority of 5-4 decisions on 20 out of the 24 cases, and in 71 of the 78 cases of the term, in line with his position as the "swing vote" of the Court.[117][118]

Facilities

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City. When Philadelphia became the capital, the Court met briefly in Independence Hall before settling in Old City Hall from 1791 until 1800. After the government moved to Washington, D.C., the Court occupied various spaces in the United States Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home. The four-story building was designed by Cass Gilbert in a classical style sympathetic to the surrounding buildings of the Capitol and Library of Congress, and is clad in marble. The building includes the courtroom, justices' chambers, an extensive law library, various meeting spaces, and auxiliary services including a gymnasium. The Supreme Court building is within the ambit of the Architect of the Capitol, but maintains its own police force separate from the Capitol Police.[119]

Located across the street from the United States Capitol at One First Street NE and Maryland Avenue,[120][121] the building is open to the public from 9 am to 4:30 pm weekdays but closed on weekends and holidays.[120] Visitors may not tour the actual courtroom unaccompanied. There is a cafeteria, a gift shop, exhibits, and a half-hour informational film.[119] When the Court is not in session, lectures about the courtroom are held hourly from 9:30 am to 3:30 pm and reservations are not necessary.[119] When the Court is in session the public may attend oral arguments, which are held twice each morning (and sometimes afternoons) on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals from October through late April, with breaks during December and February. Visitors are seated on a first-come first-served basis. One estimate is there are about 250 seats available.[122] The number of open seats varies from case to case; for important cases, some visitors arrive the day before and wait through the night. From mid-May until the end of June, the court releases orders and opinions beginning at 10 am, and these 15 to 30-minute sessions are open to the public on a similar basis.[119] Supreme Court Police are available to answer questions.[120]

Jurisdiction

Section 2 of Article Three of the United States Constitution outlines the jurisdiction of the federal courts of the United States:

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

The jurisdiction of the federal courts was further limited by the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution, which forbade federal courts from hearing cases "commenced or prosecuted against [a State] by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State." However, states may waive this immunity, and Congress may abrogate the states' immunity in certain circumstances (see Sovereign immunity). In addition to constitutional constraints, Congress is authorized by Article III to regulate the court's appellate jurisdiction. The federal courts may hear cases only if one or more of the following conditions are met:

- If there is diversity of citizenship (meaning, the parties are citizens of different states or countries, including foreign states),[123] and the amount of damages exceeds $75,000.[124]

- If the case presents a federal question, meaning that it involves a claim or issue "arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States", assuming that the question is not constitutionally committed to another branch of government.[125]

- If the United States federal government (including the Post Office)[126] is a party in the case.[127][128]

Exercise of this power can become controversial (see jurisdiction stripping). For example, 28 U.S.C. § 2241(e)(1), as amended by the Detainee Treatment Act, provides that "No court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien detained by the United States who has been determined by the United States to have been properly detained as an enemy combatant or is awaiting such determination."

The Constitution specifies that the Supreme Court may exercise original jurisdiction in cases affecting ambassadors and other diplomats, and in cases in which a state is a party. In all other cases, however, the Court has only appellate jurisdiction. It considers cases based on its original jurisdiction very rarely; almost all cases are brought to the Supreme Court on appeal. In practice, the only original jurisdiction cases heard by the Court are disputes between two or more states.

The power of the Supreme Court to consider appeals from state courts, rather than just federal courts, was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 and upheld early in the Court's history, by its rulings in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816) and Cohens v. Virginia (1821). The Supreme Court is the only federal court that has jurisdiction over direct appeals from state court decisions, although there are several devices that permit so-called "collateral review" of state cases.

Since Article Three of the United States Constitution stipulates that federal courts may only entertain "cases" or "controversies", the Supreme Court avoids deciding cases that are moot and does not render advisory opinions, as the supreme courts of some states may do. For example, in DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974), the Court dismissed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a law school affirmative action policy because the plaintiff student had graduated since he began the lawsuit, and a decision from the Court on his claim would not be able to redress any injury he had suffered. The mootness exception is not absolute. If an issue is "capable of repetition yet evading review", the Court will address it even though the party before the Court would not himself be made whole by a favorable result. In Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), and other abortion cases, the Court addresses the merits of claims pressed by pregnant women seeking abortions even if they are no longer pregnant because it takes longer than the typical human gestation period to appeal a case through the lower courts to the Supreme Court.

Justices as Circuit Justices

The United States is divided into thirteen circuit courts of appeals, each of which is assigned a "circuit justice" from the Supreme Court. Although this concept has been in continuous existence throughout the history of the republic, its meaning has changed through time.

Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, each justice was required to "ride circuit", or to travel within the assigned circuit and consider cases alongside local judges. This practice encountered opposition from many justices, who cited the difficulty of travel. Moreover, there was a potential for a conflict of interest on the Court if a justice had previously decided the same case while riding circuit. Circuit riding was abolished in 1891.

Today, the circuit justice for each circuit is responsible for dealing with certain types of applications that, under the Court's rules, may be addressed by a single justice. These include applications for emergency stays (including stays of execution in death-penalty cases) and injunctions pursuant to the All Writs Act arising from cases within that circuit, as well as routine requests such as requests for extensions of time. In the past, circuit justices also sometimes ruled on motions for bail in criminal cases, writs of habeas corpus, and applications for writs of error granting permission to appeal. Ordinarily, a justice will resolve such an application by simply endorsing it "granted" or "denied" or entering a standard form of order. However, the justice may elect to write an opinion—referred to as an in-chambers opinion—in such matters if he or she wishes.

A circuit justice may sit as a judge on the Court of Appeals of that circuit, but over the past hundred years, this has rarely occurred. A circuit justice sitting with the Court of Appeals has seniority over the chief judge of the circuit.

The chief justice has traditionally been assigned to the District of Columbia Circuit, the Fourth Circuit (which includes Maryland and Virginia, the states surrounding the District of Columbia), and since it was established, the Federal Circuit. Each associate justice is assigned to one or two judicial circuits.

As of February 25, 2016, the allotment of the justices among the circuits is:[129]

| Circuit | Justice |

|---|---|

| District of Columbia Circuit | Chief Justice Roberts |

| First Circuit | Justice Breyer |

| Second Circuit | Justice Ginsburg |

| Third Circuit | Justice Alito |

| Fourth Circuit | Chief Justice Roberts |

| Fifth Circuit | Justice Thomas |

| Sixth Circuit | Justice Kagan |

| Seventh Circuit | Justice Kagan |

| Eighth Circuit | Justice Alito |

| Ninth Circuit | Justice Kennedy |

| Tenth Circuit | Justice Sotomayor |

| Eleventh Circuit | Justice Thomas |

| Federal Circuit | Chief Justice Roberts |

Four of the current justices are assigned to circuits on which they previously sat as circuit judges: Chief Justice Roberts (D.C. Circuit), Justice Breyer (First Circuit), Justice Alito (Third Circuit), and Justice Kennedy (Ninth Circuit).

Process

A term of the Supreme Court commences on the first Monday of each October, and continues until June or early July of the following year. Each term consists of alternating periods of approximately two weeks known as "sittings" and "recesses." Justices hear cases and deliver rulings during sittings; they discuss cases and write opinions during recesses.

Case selection

Nearly all cases come before the court by way of petitions for writs of certiorari, commonly referred to as "cert." The Court may review any case in the federal courts of appeals "by writ of certiorari granted upon the petition of any party to any civil or criminal case."[130] The Court may only review "final judgments rendered by the highest court of a state in which a decision could be had" if those judgments involve a question of federal statutory or constitutional law.[131] The party that appealed to the Court is the petitioner and the non-mover is the respondent. All case names before the Court are styled petitioner v. respondent, regardless of which party initiated the lawsuit in the trial court. For example, criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the state and against an individual, as in State of Arizona v. Ernesto Miranda. If the defendant is convicted, and his conviction then is affirmed on appeal in the state supreme court, when he petitions for cert the name of the case becomes Miranda v. Arizona.

There are situations where the Court has original jurisdiction, such as when two states have a dispute against each other, or when there is a dispute between the United States and a state. In such instances, a case is filed with the Supreme Court directly. Examples of such cases include United States v. Texas, a case to determine whether a parcel of land belonged to the United States or to Texas, and Virginia v. Tennessee, a case turning on whether an incorrectly drawn boundary between two states can be changed by a state court, and whether the setting of the correct boundary requires Congressional approval. Although it has not happened since 1794 in the case of Georgia v. Brailsford,[132] parties in an action at law in which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction may request that a jury determine issues of fact.[133] Two other original jurisdiction cases involve colonial era borders and rights under navigable waters in New Jersey v. Delaware, and water rights between riparian states upstream of navigable waters in Kansas v. Colorado.

A cert petition is voted on at a session of the court called a conference. A conference is a private meeting of the nine Justices by themselves; the public and the Justices' clerks are excluded. If four Justices vote to grant the petition, the case proceeds to the briefing stage; otherwise, the case ends. Except in death penalty cases and other cases in which the Court orders briefing from the respondent, the respondent may, but is not required to, file a response to the cert petition.

The court grants a petition for cert only for "compelling reasons", spelled out in the court's Rule 10. Such reasons include:

- Resolving a conflict in the interpretation of a federal law or a provision of the federal Constitution

- Correcting an egregious departure from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings

- Resolving an important question of federal law, or to expressly review a decision of a lower court that conflicts directly with a previous decision of the Court.

When a conflict of interpretations arises from differing interpretations of the same law or constitutional provision issued by different federal circuit courts of appeals, lawyers call this situation a "circuit split." If the court votes to deny a cert petition, as it does in the vast majority of such petitions that come before it, it does so typically without comment. A denial of a cert petition is not a judgment on the merits of a case, and the decision of the lower court stands as the final ruling in the case.

To manage the high volume of cert petitions received by the Court each year (of the more than 7,000 petitions the Court receives each year, it will usually request briefing and hear oral argument in 100 or fewer), the Court employs an internal case management tool known as the "cert pool." Currently, all justices except for Justice Alito participate in the cert pool.[134][135][136]

Oral argument

When the Court grants a cert petition, the case is set for oral argument. Both parties will file briefs on the merits of the case, as distinct from the reasons they may have argued for granting or denying the cert petition. With the consent of the parties or approval of the Court, amici curiae, or "friends of the court", may also file briefs. The Court holds two-week oral argument sessions each month from October through April. Each side has thirty minutes to present its argument (the Court may choose to give more time, though this is rare),[137] and during that time, the Justices may interrupt the advocate and ask questions. The petitioner gives the first presentation, and may reserve some time to rebut the respondent's arguments after the respondent has concluded. Amici curiae may also present oral argument on behalf of one party if that party agrees. The Court advises counsel to assume that the Justices are familiar with and have read the briefs filed in a case.

Supreme Court bar

In order to plead before the court, an attorney must first be admitted to the court's bar. Approximately 4,000 lawyers join the bar each year. The bar contains an estimated 230,000 members. In reality, pleading is limited to several hundred attorneys. The rest join for a one-time fee of $200, earning the court about $750,000 annually. Attorneys can be admitted as either individuals or as groups. The group admission is held before the current justices of the Supreme Court, wherein the Chief Justice approves a motion to admit the new attorneys.[138] Lawyers commonly apply for the cosmetic value of a certificate to display in their office or on their resume. They also receive access to better seating if they wish to attend an oral argument.[139] Members of the Supreme Court Bar are also granted access to the collections of the Supreme Court Library.[140]

Decision

At the conclusion of oral argument, the case is submitted for decision. Cases are decided by majority vote of the Justices. It is the Court's practice to issue decisions in all cases argued in a particular Term by the end of that Term. Within that Term, however, the Court is under no obligation to release a decision within any set time after oral argument. At the conclusion of oral argument, the Justices retire to another conference at which the preliminary votes are tallied, and the most senior Justice in the majority assigns the initial draft of the Court's opinion to a Justice on his or her side. Drafts of the Court's opinion, as well as any concurring or dissenting opinions,[141] circulate among the Justices until the Court is prepared to announce the judgment in a particular case.

It is possible that, through recusals or vacancies, the Court divides evenly on a case. If that occurs, then the decision of the court below is affirmed, but does not establish binding precedent. In effect, it results in a return to the status quo ante. For a case to be heard, there must be a quorum of at least six justices.[142] If a quorum is not available to hear a case and a majority of qualified justices believes that the case cannot be heard and determined in the next term, then the judgment of the court below is affirmed as if the Court had been evenly divided. For cases brought to the Supreme Court by direct appeal from a United States District Court, the Chief Justice may order the case remanded to the appropriate U.S. Court of Appeals for a final decision there.[143] This has only occurred once in U.S. history, in the case of United States v. Alcoa (1945).[144]

Published opinions

The Court's opinions are published in three stages. First, a slip opinion is made available on the Court's web site and through other outlets. Next, several opinions and lists of the court's orders are bound together in paperback form, called a preliminary print of United States Reports, the official series of books in which the final version of the Court's opinions appears. About a year after the preliminary prints are issued, a final bound volume of U.S. Reports is issued. The individual volumes of U.S. Reports are numbered so that users may cite this set of reports—or a competing version published by another commercial legal publisher but containing parallel citations—to allow those who read their pleadings and other briefs to find the cases quickly and easily.

As of the beginning of October Term 2014, there are:

- 557 final bound volumes of U.S. Reports, covering cases through the end of October Term 2008, which ended on October 2, 2009.[145]

- 4 volumes' worth of soft-cover preliminary prints (volumes 558–561), covering cases for October Term 2009[146]

- 12 volumes' worth of opinions available in slip opinion form (volumes 562–573)[146]

As of March 2012, the U.S. Reports have published a total of 30,161 Supreme Court opinions, covering the decisions handed down from February 1790 to March 2012. This figure does not reflect the number of cases the Court has taken up, as several cases can be addressed by a single opinion (see, for example, Parents v. Seattle, where Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education was also decided in the same opinion; by a similar logic, Miranda v. Arizona actually decided not only Miranda but also three other cases: Vignera v. New York, Westover v. United States, and California v. Stewart). A more unusual example is The Telephone Cases, which comprise a single set of interlinked opinions that take up the entire 126th volume of the U.S. Reports.

Opinions are also collected and published in two unofficial, parallel reporters: Supreme Court Reporter, published by West (now a part of Thomson Reuters), and United States Supreme Court Reports, Lawyers' Edition (simply known as Lawyers' Edition), published by LexisNexis. In court documents, legal periodicals, and other legal media, case citations generally contain the cites from each of the three reporters; for example, the citation to Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission is presented as Citizens United v. Federal Election Com'n, 585 U.S. 50, 130 S. Ct. 876, 175 L. Ed. 2d 753 (2010), with "S. Ct." representing the Supreme Court Reporter, and "L. Ed." representing the Lawyers' Edition.[147][148]

Citations to published opinions

Lawyers use an abbreviated format to cite cases, in the form "vol U.S. page, pin (year)", where vol is the volume number, page is the page number on which the opinion begins, and year is the year in which the case was decided. Optionally, pin is used to "pinpoint" to a specific page number within the opinion. For instance, the citation for Roe v. Wade is 410 U.S. 113 (1973), which means the case was decided in 1973 and appears on page 113 of volume 410 of U.S. Reports. For opinions or orders that have not yet been published in the preliminary print, the volume and page numbers may be replaced with "___".

Institutional powers and constraints

The Federal court system and the judicial authority to interpret the Constitution received little attention in the debates over the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. The power of judicial review, in fact, is nowhere mentioned in it. Over the ensuing years, the question of whether the power of judicial review was even intended by the drafters of the Constitution was quickly frustrated by the lack of evidence bearing on the question either way.[149] Nevertheless, the power of judiciary to overturn laws and executive actions it determines are unlawful or unconstitutional is a well-established precedent. Many of the Founding Fathers accepted the notion of judicial review; in Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton wrote: "A Constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute."

The Supreme Court firmly established its power to declare laws unconstitutional in Marbury v. Madison (1803), consummating the American system of checks and balances. In explaining the power of judicial review, Chief Justice John Marshall stated that the authority to interpret the law was the particular province of the courts, part of the duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. His contention was not that the Court had privileged insight into constitutional requirements, but that it was the constitutional duty of the judiciary, as well as the other branches of government, to read and obey the dictates of the Constitution.[150]

Since the founding of the republic, there has been a tension between the practice of judicial review and the democratic ideals of egalitarianism, self-government, self-determination and freedom of conscience. At one pole are those who view the Federal Judiciary and especially the Supreme Court as being "the most separated and least checked of all branches of government."[151] Indeed, federal judges and justices on the Supreme Court are not required to stand for election by virtue of their tenure "during good behavior", and their pay may "not be diminished" while they hold their position (Section 1 of Article Three). Though subject to the process of impeachment, only one Justice has ever been impeached and no Supreme Court Justice has been removed from office. At the other pole are those who view the judiciary as the least dangerous branch, with little ability to resist the exhortations of the other branches of government.[150] The Supreme Court, it is noted, cannot directly enforce its rulings; instead, it relies on respect for the Constitution and for the law for adherence to its judgments. One notable instance of nonacquiescence came in 1832, when the state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court's decision in Worcester v. Georgia. President Andrew Jackson, who sided with the Georgia courts, is supposed to have remarked, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!";[152] however, this alleged quotation has been disputed. Some state governments in the South also resisted the desegregation of public schools after the 1954 judgment Brown v. Board of Education. More recently, many feared that President Nixon would refuse to comply with the Court's order in United States v. Nixon (1974) to surrender the Watergate tapes. Nixon, however, ultimately complied with the Supreme Court's ruling.

Supreme Court decisions can be (and have been) purposefully overturned by constitutional amendment, which has happened on five occasions:

- Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) – overturned by the Eleventh Amendment (1795)

- Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) – overturned by the Thirteenth Amendment (1865) and the Fourteenth Amendment (1868)

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895) – overturned by the Sixteenth Amendment (1913)

- Minor v. Happersett (1875) – overturned by the Nineteenth Amendment (1920)

- Oregon v. Mitchell (1970) – overturned by the Twenty-sixth Amendment (1971)

When the Court rules on matters involving the interpretation of laws rather than of the Constitution, simple legislative action can reverse the decisions (for example, in 2009 Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter act, superseding the limitations given in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. in 2007). Also, the Supreme Court is not immune from political and institutional consideration: lower federal courts and state courts sometimes resist doctrinal innovations, as do law enforcement officials.[153]

In addition, the other two branches can restrain the Court through other mechanisms. Congress can increase the number of justices, giving the President power to influence future decisions by appointments (as in Roosevelt's Court Packing Plan discussed above). Congress can pass legislation that restricts the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and other federal courts over certain topics and cases: this is suggested by language in Section 2 of Article Three, where the appellate jurisdiction is granted "with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make." The Court sanctioned such congressional action in the Reconstruction case ex parte McCardle (1869), though it rejected Congress' power to dictate how particular cases must be decided in United States v. Klein (1871).

On the other hand, through its power of judicial review, the Supreme Court has defined the scope and nature of the powers and separation between the legislative and executive branches of the federal government; for example, in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936), Dames & Moore v. Regan (1981), and notably in Goldwater v. Carter (1979), (where it effectively gave the Presidency the power to terminate ratified treaties without the consent of Congress or the Senate). The Court's decisions can also impose limitations on the scope of Executive authority, as in Humphrey's Executor v. United States (1935), the Steel Seizure Case (1952), and United States v. Nixon (1974).

Law clerks

Each Supreme Court justice hires several law clerks to review petitions for writ of certiorari, research them, prepare bench memorandums, and draft opinions. Associate justices are allowed four clerks. The chief justice is allowed five clerks, but Chief Justice Rehnquist hired only three per year, and Chief Justice Roberts usually hires only four.[154] Generally, law clerks serve a term of one to two years.

The first law clerk was hired by Associate Justice Horace Gray in 1882.[154][155] Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Louis Brandeis were the first Supreme Court justices to use recent law school graduates as clerks, rather than hiring a "stenographer-secretary".[156] Most law clerks are recent law school graduates.

The first female clerk was Lucile Lomen, hired in 1944 by Justice William O. Douglas.[154] The first African-American, William T. Coleman, Jr., was hired in 1948 by Justice Felix Frankfurter.[154] A disproportionately large number of law clerks have obtained law degrees from elite law schools, especially Harvard, Yale, the University of Chicago, Columbia, and Stanford. From 1882 to 1940, 62% of law clerks were graduates of Harvard Law School.[154] Those chosen to be Supreme Court law clerks usually have graduated in the top of their law school class and were often an editor of the law review or a member of the moot court board. In recent times, clerking previously for a judge in a federal circuit court has been a prerequisite to clerking for a Supreme Court justice.

Six Supreme Court justices previously clerked for other justices: Byron White clerked for Frederick M. Vinson, John Paul Stevens clerked for Wiley Rutledge, Stephen Breyer clerked for Arthur Goldberg, William H. Rehnquist clerked for Robert H. Jackson, John G. Roberts, Jr. clerked for William H. Rehnquist, and Elena Kagan clerked for Thurgood Marshall. Many of the justices have also clerked in the federal Courts of Appeals. Justice Samuel Alito clerked for Judge Leonard I. Garth of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and Elena Kagan clerked for Judge Abner J. Mikva of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Politicization of the Court

Clerks hired by each of the justices of the Supreme Court are often given considerable leeway in the opinions they draft. "Supreme Court clerkship appeared to be a nonpartisan institution from the 1940s into the 1980s", according to a study published in 2009 by the law review of Vanderbilt University Law School.[157][158] "As law has moved closer to mere politics, political affiliations have naturally and predictably become proxies for the different political agendas that have been pressed in and through the courts", former federal court of appeals judge J. Michael Luttig said.[157] David J. Garrow, professor of history at the University of Cambridge, stated that the Court had thus begun to mirror the political branches of government. "We are getting a composition of the clerk workforce that is getting to be like the House of Representatives", Professor Garrow said. "Each side is putting forward only ideological purists."[157]

According to the Vanderbilt Law Review study, this politicized hiring trend reinforces the impression that the Supreme Court is "a superlegislature responding to ideological arguments rather than a legal institution responding to concerns grounded in the rule of law."[157]

A poll conducted in June 2012 by The New York Times and CBS News showed that just 44 percent of Americans approve of the job the Supreme Court is doing. Three-quarters said the justices' decisions are sometimes influenced by their political or personal views.[159]

Criticism

The court has been the object of criticisms on a range of issues. Among them:

- Judicial activism: The Supreme Court has been criticized for not keeping within Constitutional bounds by engaging in judicial activism, rather than merely interpreting law and exercising judicial restraint. Claims of judicial activism are not confined to any particular ideology.[160] An often cited example of conservative judicial activism is the 1905 decision in Lochner v. New York, which has been criticized by many prominent thinkers, including Robert Bork, Justice Antonin Scalia, and Chief Justice John Roberts.[160][161] An often cited example of liberal judicial activism is Roe v. Wade (1973), which legalized abortion in part on the basis of the "right to privacy" expressed in the Fourteenth Amendment, a reasoning that some critics argued was circuitous.[160] Legal scholars,[162][163] justices,[164] and presidential candidates[165] have criticized the Roe decision. The progressive Brown v. Board of Education decision has been criticized by conservatives such as Patrick Buchanan[166] and former presidential contender Barry Goldwater.[167] More recently, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was criticized for changing the long-standing view that the first amendment did not apply to the corporation.[168] Lincoln warned, referring to the Dred Scott decision, that if government policy became "irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court...the people will have ceased to be their own rulers."[169] Former justice Thurgood Marshall justified judicial activism with these words: "You do what you think is right and let the law catch up."[170] During different historical periods, the Court has leaned in different directions.[171][172] Critics from both sides complain that activist-judges abandon the Constitution and substitute their own views instead.[173][174][175] Critics include writers such as Andrew Napolitano,[176] Phyllis Schlafly,[177] Mark R. Levin,[178] Mark I. Sutherland,[179] and James MacGregor Burns.[180][181] Past presidents from both parties have attacked judicial activism, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan.[182][183] Failed Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork wrote: "What judges have wrought is a coup d'état, – slow-moving and genteel, but a coup d'état nonetheless."[184] Senator Al Franken quipped that when politicians talk about judicial activism, "their definition of an activist judge is one who votes differently than they would like."[185] One law professor claimed in a 1978 article that the Supreme Court is in some respects "certainly a legislative body."[186]

- Failing to protect individual rights: Court decisions have been criticized for failing to protect individual rights: the Dred Scott (1857) decision upheld slavery;[187] Plessy v Ferguson (1896) upheld segregation under the doctrine of separate but equal;[188] Kelo v. City of New London (2005) was criticized by prominent politicians, including New Jersey governor Jon Corzine, as undermining property rights.[189][190] A student criticized a 1988 ruling that allowed school officials "to block publication of a student article in the high school newspaper."[191] Some critics suggest the 2009 bench with a conservative majority has "become increasingly hostile to voters" by siding with Indiana's voter identification laws which tend to "disenfranchise large numbers of people without driver's licenses, especially poor and minority voters", according to one report.[192] Senator Al Franken criticized the Court for "eroding individual rights."[185] However, others argue that the Court is too protective of some individual rights, particularly those of people accused of crimes or in detention. For example, Chief Justice Warren Burger was an outspoken critic of the exclusionary rule, and Justice Scalia criticized the Court's decision in Boumediene v. Bush for being too protective of the rights of Guantanamo detainees, on the grounds that habeas corpus was "limited" to sovereign territory.[193]

- Supreme Court has too much power: This criticism is related to complaints about judicial activism. George Will wrote that the Court has an "increasingly central role in American governance."[194] It was criticized for intervening in bankruptcy proceedings regarding ailing carmaker Chrysler Corporation in 2009.[195] A reporter wrote that "Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's intervention in the Chrysler bankruptcy" left open the "possibility of further judicial review" but argued overall that the intervention was a proper use of Supreme Court power to check the executive branch.[195] Warren E. Burger, before becoming Chief Justice, argued that since the Supreme Court has such "unreviewable power" it is likely to "self-indulge itself" and unlikely to "engage in dispassionate analysis".[196] Larry Sabato wrote "excessive authority has accrued to the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court."[197]

- Courts are poor check on executive power: British constitutional scholar Adam Tomkins sees flaws in the American system of having courts (and specifically the Supreme Court) act as checks on the Executive and Legislative branches; he argues that because the courts must wait, sometimes for years, for cases to wend their way through the system, their ability to restrain the other two branches is severely weakened.[198][199] In contrast, the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany for example, can directly declare a law unconstitutional upon request.

- Federal versus state power: There has been debate throughout American history about the boundary between federal and state power. While Framers such as James Madison[200] and Alexander Hamilton[201] argued in The Federalist Papers that their then-proposed Constitution would not infringe on the power of state governments,[202][203][204][205] others argue that expansive federal power is good and consistent with the Framers' wishes.[206] The Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution explicitly grants "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." The Supreme Court has been criticized for giving the federal government too much power to interfere with state authority. One criticism is that it has allowed the federal government to misuse the Commerce Clause by upholding regulations and legislation which have little to do with interstate commerce, but that were enacted under the guise of regulating interstate commerce; and by voiding state legislation for allegedly interfering with interstate commerce. For example, the Commerce Clause was used by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals to uphold the Endangered Species Act, thus protecting six endemic species of insect near Austin, Texas, despite the fact that the insects had no commercial value and did not travel across state lines; the Supreme Court let that ruling stand without comment in 2005.[207] Chief Justice John Marshall asserted Congress's power over interstate commerce was "complete in itself, may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowledges no limitations, other than are prescribed in the Constitution."[208] Justice Alito said congressional authority under the Commerce Clause is "quite broad."[209] Modern day theorist Robert B. Reich suggests debate over the Commerce Clause continues today.[208] Advocates of states' rights such as constitutional scholar Kevin Gutzman have also criticized the Court, saying it has misused the Fourteenth Amendment to undermine state authority. Justice Brandeis, in arguing for allowing the states to operate without federal interference, suggested that states should be laboratories of democracy.[210] One critic wrote "the great majority of Supreme Court rulings of unconstitutionality involve state, not federal, law."[211] However, others see the Fourteenth Amendment as a positive force that extends "protection of those rights and guarantees to the state level."[212]

- Secretive proceedings: The Court has been criticized for keeping its deliberations hidden from public view.[213] According to a review of Jeffrey Toobin's expose The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court; "Its inner workings are difficult for reporters to cover, like a closed "cartel", only revealing itself through "public events and printed releases, with nothing about its inner workings".[214] The reviewer writes: "few (reporters) dig deeply into court affairs. It all works very neatly; the only ones hurt are the American people, who know little about nine individuals with enormous power over their lives."[214] Larry Sabato complains about the Court's "insularity."[197] A Fairleigh Dickinson University poll conducted in 2010 found that 61% of American voters agreed that televising Court hearings would "be good for democracy", and 50% of voters stated they would watch Court proceedings if they were televised.[215][216] In recent years, many justices have appeared on television, written books, and made public statements to journalists.[217][218] In a 2009 interview on C-SPAN, journalists Joan Biskupic (of USA Today) and Lyle Denniston (of SCOTUSblog) argued that the Court is a "very open" institution, with only the justices' private conferences being inaccessible to others.[217] In October 2010, the Court began the practice of posting on its website recordings and transcripts of oral arguments on the Friday after they take place.

- Judicial interference in political disputes: Some Court decisions have been criticized for injecting the Court into the political arena, and deciding questions that are the purview of the other two branches of government. The Bush v. Gore decision, in which the Supreme Court intervened in the 2000 presidential election and effectively chose George W. Bush over Al Gore, has been criticized extensively, particularly by liberals.[214][219][220][221][222][223] Another example are Court decisions on apportionment and re-districting: in Baker v. Carr, the court decided it could rule on apportionment questions; Justice Frankfurter in a "scathing dissent" argued against the court wading into so-called political questions.[224]

- Not choosing enough cases to review: Senator Arlen Specter said the Court should "decide more cases".[185] On the other hand, although Justice Scalia acknowledged in a 2009 interview that the number of cases that the Court hears now is smaller today than when he first joined the Supreme Court, he also stated that he has not changed his standards for deciding whether to review a case, nor does he believe his colleagues have changed their standards. He attributed the high volume of cases in the late 1980s, at least in part, to an earlier flurry of new federal legislation that was making its way through the courts.[217]

- Lifetime tenure: Critic Larry Sabato wrote: "The insularity of lifetime tenure, combined with the appointments of relatively young attorneys who give long service on the bench, produces senior judges representing the views of past generations better than views of the current day."[197] Sanford Levinson has been critical of justices who stayed in office despite medical deterioration based on longevity.[225] James MacGregor Burns stated lifelong tenure has "produced a critical time lag, with the Supreme Court institutionally almost always behind the times."[180] Proposals to solve these problems include term limits for justices, as proposed by Levinson[226] and Sabato[197][227] as well as a mandatory retirement age proposed by Richard Epstein,[228] among others.[229] However, others suggest lifetime tenure brings substantial benefits, such as impartiality and freedom from political pressure. Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 78 wrote "nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence as permanency in office."[230]

- Accepting gifts: The 21st century has seen increased scrutiny of justices accepting expensive gifts and travel. All of the members of the Roberts Court have accepted travel or gifts. In 2012, Justice Sonia Sotomayor received $1.9 million in advances from her publisher Knopf Doubleday.[231] Justice Scalia and others took dozens of expensive trips to exotic locations paid for by private donors.[232] Private events sponsored by partisan groups that are attended by both the justices and those who have an interest in their decisions have raised concerns about access and inappropriate communications.[233] Stephen Spaulding, the legal director at Common Cause, said, "There are fair questions raised by some of these trips about their commitment to being impartial."[232]

See also

- 2016 U.S. Supreme Court vacancy

- Barack Obama Supreme Court candidates

- Federal judicial appointment history

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law schools attended by United States Supreme Court Justices

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- Lists of United States Supreme Court cases

- Oyez Project

- Segal–Cover score

- Unsuccessful nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States

- Landmark Supreme Court decisions (selection)

- Marbury v. Madison (1803, judicial review)

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819, implied powers)

- Gibbons v. Ogden (1824, interstate commerce)

- Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857, slavery)

- Plessy v. Ferguson (1896, separate but equal treatment of races)

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954, school segregation of races)

- Engel v. Vitale (1962, state-sponsored prayers in public schools)

- Abington School District v. Schempp (1963, Bible readings and recitation of the Lord's prayer in U.S. public schools)

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963, right to an attorney)

- Griswold v. Connecticut (1965, privacy in marriage)

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966, rights of those detained by police)

- In re Gault (1967, rights of juvenile suspects)

- Loving v. Virginia (1967, interracial marriage)

- Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971, religious activities in public schools)

- New York Times Co. v. United States (1971, freedom of the press)

- Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972, privacy for unmarried people)

- Roe v. Wade (1973, abortion)

- Miller v. California (1973, obscenity)

- Buckley v. Valeo (1976, campaign finance)

- Bowers v. Hardwick (1986, sodomy)

- Bush v. Gore (2000, presidential election)

- Lawrence v. Texas (2003, sodomy, privacy)

- District of Columbia v. Heller (2008, gun rights)

- Citizens United v. FEC (2010, campaign finance)

- United States v. Windsor (2013, same-sex marriage)

- Obergefell v. Hodges (2015, same-sex marriage)

References

- ↑ Safire, William, "On language: POTUS and FLOTUS," New York Times, October 12, 1997. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Barnabas. Almanac of the Federal Judiciary, p. 25 (Aspen Law & Business, 1988).

- ↑ "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ↑ Bordewich, Fergus (2016). The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government. Simon & Schuster. p. 195. ISBN 1451691939.

- ↑ Shugerman, Jed. "A Six-Three Rule: Reviving Consensus and Deference on the Supreme Court", Georgia Law Review, Vol. 37, p. 893 (2002–03).

- ↑ Irons, Peter. A People's History of the Supreme Court, p. 101 (Penguin 2006).

- ↑ Ashmore, Anne (August 2006). "Dates of Supreme Court decisions and arguments, United States Reports volumes 2–107 (1791–82)" (PDF). Library, Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ↑ Scott Douglas Gerber (editor) (1998). "Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall". New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-3114-7. Retrieved October 31, 2009.