Orcein

Orcein, also archil, orchil, lacmus and C.I. Natural Red 28, are names for dyes extracted from several species of lichen, commonly known as "orchella weeds", found in various parts of the world. A major source is the archil lichen, Roccella tinctoria. Orcinol is extracted from such lichens. It is then converted to orcein by ammonia and air. In traditional dye-making methods, urine was used as the ammonia source. If the conversion is carried out in the presence of potassium carbonate, calcium hydroxide, and calcium sulfate (in the form of potash, lime, and gypsum in traditional dye-making methods), the result is litmus, a more complex molecule.[1] The manufacture was described by Cocq in 1812 [2] and in the UK in 1874.[3] Roberts noted orchilla as a principal export of the Cape Verde islands, superior to the same kind of moss found in Italy or the Canaries, that in 1832 was yielding an annual revenue of $200,000.[4]:pp.14,15 Commercial archil is either a powder (called cudbear) or a paste. It is red in acidic pH and blue in alkaline pH.

Orcein is not approved as a food dye (banned in Europe since January 1977), with E number E121 before 1977 and E182 after.[5],[6] Its CAS number is

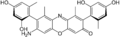

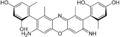

The chemical components of orcein were elucidated only in the 1950s by Hans Musso.[7] The structures are shown below. A paper originally published in 1961, embodying most of Musso's work on components of orcein and litmus, was translated into English and published in 2003[8] in a special issue of the journal Biotechnic & Histochemistry (Vol 78, No. 6) devoted to the dye. A single alternative structural formula for orcein, possibly incorrect, is given by the National Library of Medicine and Emolecules .

Orcein is a reddish-brown dye, orchil is a purple-blue dye. Orcein is also used as a stain in microscopy to visualize chromosomes,[9] elastic fibers,[10] Hepatitis B surface antigens,[11] and copper-associated proteins.[12]

Cudbear

Cudbear is a dye extracted from orchil lichens that produces colours in the purple range. It can be used to dye wool and silk, without the use of mordant.

Cudbear was developed by Dr Cuthbert Gordon of Scotland: production began in 1758, and it was patented in 1758, British patent 727 . The lichen is first boiled in a solution of ammonium carbonate. The mixture is then cooled and ammonia is added and the mixture is kept damp for 3–4 weeks. Then the lichen is dried and ground to powder. The manufacture details were carefully protected, with a ten-feet high wall being built around the manufacturing facility, and staff consisting of Highlanders sworn to secrecy. The lichen consumption soon reached 250 tons per year and import from Norway and Sweden had to be arranged.

Cudbear was the first dye to be invented in modern times, and one of the few dyes to be credited to a named individual.

A similar process was developed in France. The lichen is extracted by urine or ammonia, then the extract is acidified, the dissolved dye precipitates out and is washed. Then it is dissolved in ammonia again, the solution is heated in air until it becomes purple, then it is precipitated out with calcium chloride. The resulting insoluble purple solid is known as French purple, a fast lichen dye that was much more stable than other lichen dyes.

Gallery

-

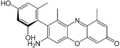

α-amino orcein

-

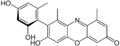

α-hydroxy orcein

-

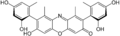

β-amino orcein

-

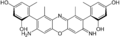

β-hydroxy orcein

-

β-amino orceinimine

-

γ-amino orcein

-

γ-hydroxy orcein

-

γ-amino orceinimine

See also

References

- ↑ Beecken, H; E-M Gottschalk; U v Gizycki; et al. (2003). "Orcein and litmus". Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 78 (6): 289–302. doi:10.1080/10520290410001671362.

- ↑ Cocq M. (1812). Mémoire sur la fabrication et l'emploi de l'orseille. Annales de Chimie 81:258–278. Cited in: Chevreul ME. (1830). Leçons de chimie appliquée à la teinture. Paris: Pichon et Didier. p 114–116.

- ↑ Workman, A Leeds (1874). "Manufacture of Archil and Cudbear". Chemical News. 30 (173): 143.

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund (Digitized 12 October 2007) [First published in 1837]. Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat : in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock ... during the years 1832-3-4. Harper & brothers. OCLC 12212199. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ http://www.additifs-alimentaires.net/E121.php?src_reg

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/ColorAdditives/ColorAdditiveInventories/ucm106626.htm

- ↑ Musso, H (1960). "Orcein- und Lackmusfarbstoffe: Konstitutionsermittlung und Konstitutionsbeweis durch die Synthese. (Orcein and litmus pigments: constitutional elucidation and constitutional proof by synthesis.)". Planta Medica. 8: 431–446. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1101580.

- ↑ Beecken, H; Gottschalk, EM; von Gizycki, U; Kramer, H; Maassen, D; Matthies, HG; Musso, H; Rathjen, C; Zdhorsky, UI (2003). "Orcein and litmus". Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 78: 289–302. doi:10.1080/10520290410001671362.

- ↑ La Cour, L (1941). "Acetic-orcein: a new stain-fixative for chromosomes". Stain Technology. 16: 169–174. doi:10.3109/10520294109107302.

- ↑ Friedberg, SH; Goldstein, DJ (1969). "Thermodynamics of orcein staining of elastic fibres". Histochemical Journal. 1: 261–376.

- ↑ Fredenburgh, JL; Edgerton, SM; Parker, AE (1978). "A modification of the aldehyde fuchsin and orcein stains for hepatitis B surface antigen in tissue and a proposed chemical mechanism". Journal of Histotechnology. 1: 223–228. doi:10.1179/his.1978.1.6.223.

- ↑ Henwood, A (2003). "Current applications of orcein in histochemistry. A brief review with some new observations concerning influence of dye batch variation and aging of dye solutions on staining". Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 78: 303–308. doi:10.1080/10520290410001671335.