Daivadnya Brahmin

Shett gentlemen from Goa, from late 18th to early 19th century (Courtesy: Gomant Kalika, Nutan Samvatsar Visheshank, April 2002) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

|

Goa, Coastal and west Maharashtra, Coastal and central Karnataka Populations in: | |

| Languages | |

|

Dialects of primarily Konkani and Marathi are spoken as the native tongues and are used for written communication. Kannada, Gujarati, Malayalam, Tulu, and Hindi may be sometimes spoken outside home. English is commonly used for education and formal communication. Sanskrit is used for all religious purposes. | |

| Religion | |

| Brahminical Hinduism: Smarta or the Mādhva tradition | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Scythians, Goan Catholics, Mangalorean Catholics, Karwari Catholics |

The Daivadnya or Daivajña is an ethno-religious community and a Hindu Brahmin caste of the west coast of India, predominantly residing in the states of Goa, coastal Karnataka, and coastal Maharashtra. The state of Goa is considered to be the original homeland of Daivadnyas. They are believed to have flourished and prospered in Goa and hence sometimes they are called Gomantaka Daivadnya. Due to many socio-economic reasons, they emigrated to different parts of India within the last few centuries.[1]

They are commonly known as Śeṭ in the coastal region. The word Śeṭ is a corrupt form of the word Śreṣṭha or Śreṣṭhin, which could mean excellent, distinguished, or superior.[2][3] Over time the word was transformed from Śreṣṭha to Śeṭ.[4] Most of the older generation from the Daivadnya community in Goa call themselves Śeṭī Bāmaṇ, which is a corrupt form of Śreṣṭhi Brāhmaṇa. The Portuguese referred these people as Xete (cf. Xett, Xete) or sometimes Chatim (cf. Xatim), which is now Cyātī in the Konkani language; the word was a Portuguese appellation for "trader" derived from the local word Śreṣṭhin.[5] Śeṭs are often called Daivadnya Suvarṇakara (cf. Svarṇakāra).[l]

Etymology

Their name has many alternate spellings, including Daivajna, Daivajnya,Daivagna, Daiwadnya, and Daivadnea.[6][7] It is pronounced [d̪aivaɡna] in Karnataka and [d̪əivaʝɲa] in Goa and Maharashtra.

It is possible that Vadirajatirtha bestowed the appellation Daivadnya when many of the community adopted the Madhwa religion under leadership of Vadiraja.[8]

Daiva jānati iti daivajñaḥ is literally translated as the one who knows the fate is Daivadnya or "the one who knows about God is Daivadnya", and can be interpreted as the one who knows about the future is a Daivadnya; or the one is well versed in Śilpaśāstra and can craft an idol of God is called a Daivadnya.[3][9]

An alternate proposition relates to the Vedas Taittariya Samhita and Shatapatha Brahmana in which the sage Kashyapa is recorded as an eminent artisan. His book Kashyapa Samhita, along with Bhrigu Samhita and Maya Samhita recognises Daivadnya as an assistant engineer. Their work was like that of a draughtsman or evaluator. It is said that astrology began from this class of Vedic Daivadnyas, so the term Daivadnya became equivalent to astrologer.[10]

Appellations

They commonly call themselves Śeṭ to distinguish themselves from other groups who were of mixed origin and claim superiority over them.[4] The guild or members of the guilds of traders, merchants, and their employees who were mainly artisans, craftsmen, and husband-men in ancient Goa like elsewhere in ancient India, were called Śreṇī, and the head of the guilds were called Śreṣṭha or Śreṣṭhī which meant His Excellency.[11][12]

Old Portuguese documents mention them as Arie Brahmavranda Daivadnea or Aria Daivadnea Orgon Somudai, transliterated as Ārya Daivajña Varga Samudāya, translated as Aryans of the Daivadnya community.[13] They are sometimes mentioned as Daivdneagotris.[14]

Being inhabitants of Konkan they were also called as Konkanastha Daivadnya.[15]

History

Perception of their ancient history

The Seṭs are descendants of the Bhojakas and have inherited the art of crafting an idol from the Bhojakas. Bhojakas are also called Gaṇakas, which is synonymous with Daivadnya.[16][17]

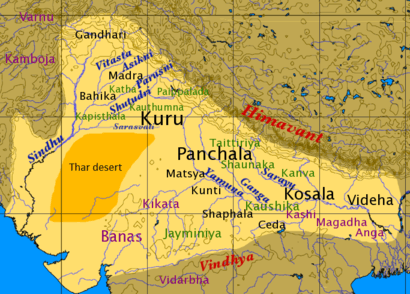

According to the mythological chronicle Sahyadrikhanda of Skanda Purana,[18] 96 Brahmin families belonging to ten gotras migrated to Goa from Brahmāvarta via Saurashtra,[19] and settled in different Agrahāras (Brahmin streets or neighbourhoods). The Daivadnyas came with Parashurama in 2500 BC[20] to the south to assist other Brahmins to perform yajna (ritualistic sacrifices) and are believed to have settled in various Agrahāras with other Brahmins. Elsewhere in the same work the author has argued that Parashurama had brought only Saraswat Brahmins.[21] Some scholars argue that this tribe migrated to Goa in the fourth to sixth century AD, some say 700 BC, and some estimate 2500 BC; this is merely a speculation and not the reality. Research by scholars like Dharmananda Damodar Kosambi[22] and Bhau Daji[23] have stated that there is no relation between Parashurama and the migration of the Brahmins. The Sahyadrikhaṇḍa is a later inclusion in the original Sanskrit Skanda Puraṇa, not a part of the original Sanskrit text.[24] The Parashurama legend serves as a symbol of the Sanskritisation that, then Goan culture experienced with the advent of Brahminical religion to this region.[25]

Many Vedic scholars like Veṅgaḍācārya[26] and Nārāyaṇaśastri Kṣirasāgara[27] relate the Daivadnya Brahmins with the Vedic Rathakara. Saṃskṛtā texts such as Jātiviveka,Saṅkha smṛti, and Añjabila state that they are one of the Rathakāras, called Upabrāhmaṇa, or minor Brahmins for whom vedic Saṃskāra are explicitly stated as mentioned in Śaivāgama.[28] The Hindu doctrines Hiraṇyakeśisutra and Bṛhajjātiviveka mention different types of Rathakaras. Most of them can be called Saṅkara Jāti or mixed caste, and their social status varies from that of a Brahmin to those considered fallen or degraded.[29] Modern scholars like Ad. Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama Śiroḍkara[29] and Bā. Da. Sātoskar[30] disagree with this claim. Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama Śiroḍkara states that if they are related to any Rathakara tribe, they belong to the Rathakara mentioned in the Rigveda, and not other Rathakaras, which are of impure descent.[29]

Alternate theories

The Magas, Aṅgiras, Bhṛgus, and the present-day Daivadnyas

Assuming that the Indo-Aryan migration theory to be true, Indologists like Dr Ghurye have speculated that the Magas and the Aṅgiras are the same and they are Proto-Indo-Europeans who reached India before the Indo-Aryans., Vedic society was divided into three races: the Aṅgiras, the Bhṛgus, and the others. These three groups later intermarried, and thus all the Brahminical Gotra Ṛṣis belonging to Aṅgira and Bhṛgus linage were born. The Magas are considered the ancestors of the Aṅgiras, and from these Magas, who married the Bhojaka women, modern-day Daivadnyas have descended. Magas are not different from the Indo-Aryans, but their period of migrations differs.[31] According to Indologist Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi, Tvaṣṭr was a deity who belonged to the clan of the Bhṛgus and existed before the Vedic era.[32] This claim is disputed by many.

Oral traditions

Oral tradition[g] of some of the Daivajna clans say that they came from Gauḍa Deśa with their Kuldevatās (family deities). There is no written evidence to support this traditional belief.

Medieval and modern history

Migrations

According to Viṭhṭhala Mitragotrī, the migration to Goa dates back to the early 4th to 6th century AD.[33] Bā. Da. Sātoskār suggests that they are a part of the Sārasvata tribe and reached Goa around 700 BC. From 1352 to 1366 AD Goa was ruled by Khiljī. In 1472, the Bahāmanī Muslims attacked, demolished many temples, and forced the Hindus to convert to Islam. To avoid this religious persecution, several Śeṭ families fled to the neighbourhood kingdom of Sondā.[34][35] Several families from western India had settled down in Kashi since the late 13th century.[36]

In 1510 the Portuguese invaded Goa. King John III of Portugal issued a decree threatening expulsion or execution of non-believers in Christianity in 1559 AD; the Daivadnyas refused conversion and had to decamp. Thousands of Daivadnya families fled to the interior of Maharashtra and coastal Karnataka.[37] About 12,000 families from the Sāsaṣṭī region of Goa (from Rāy, Kuṅkalī, Loṭalī, Verṇe and other places), mostly of the Śeṇavīs and the Śeṭs, including Vaiśyas, Kuṇbīs, and others, departed by ship to the southern ports of Honnāvara to Kozhikode.[37][38] A considerable number of the Śeṭs from Goa settled in the Ṭhāṇe district of Maharashtra, especially the Tansa River valley, after the Portuguese conquest of Goa.[39]

Portuguese period

Daivajnas and Christianity

The Portuguese imposed heavy restrictions on all Goan Hindus, but the Śeṭs were granted exemption from certain obligations or liabilities. It is rare to find a Christian Goan Śeṭ, while all the other castes find some representation in the convert society;[40] this is because the economic power the Śeṭs wielded in the sixteenth century enabled them to live and work in Goa on their own terms or emigrate with their religion intact.[40] Their commercial knowledge and skills were held in high esteem by the Portuguese;[40] because of the protection the Portuguese gave them, they had a little religious freedom.[12] For example, they were permitted to wear the horizontal Vibhutī caste-mark on the forehead, and were even exempted from punishment when they committed crimes.[12] The very few who converted were assigned the caste of Bamonn among the Goan Catholics. According to the gazetteer of Goa state they are called Catholic Śeṭs,[41] but no such distinction is found amongst Goan Catholics. A detailed study of Comunidades[h] shows that baptised Śeṭs were categorised as Bamonns. A few historians have categorised them into the category of Sudirs or Śudras because the appellation they used, Chatim, was sometimes used by the lower castes. Whether Hindu or Catholic, the community always enjoyed their social status, and were permitted to remain in Christianized parts of Goa, provided they kept a low profile, observed certain disciplines, and paid a tax of three xeraphims of (gold mohor) annually to the Portuguese.[42]

A few Daivadnya families who converted to Catholicism migrated to Mangalore due to attacks by the Marathas in Goa during the late 17th and early 18th century.[43][44]

Relationships with other communities

The trade in Goa was mainly in the hands of three rival communities classes, being the Seṭs, the Gaud Saraswat Brahmins and the Vanis.[45] The Gaud Saraswat Brahmins looked down upon the Daivadnya. The conflicts between these two communities over social status was evidenced in arguments about use of traditional Brahmin and Kshatriya emblems during religious rituals, functions and festivals.[46] The hatred was so severe until the 19th century that only fear of the police kept the peace. Later, the Portuguese banned the use of Hindu symbols and wedding festival processions.[46] Seṭs were one of the building blocks of the comunidade system in Goa,[1] and participated in the temple Mahājani system. The Saraswats Brahmins deprived the Daivadnyas as Mahajans of some of the temples because of the political power they once experienced.[47]

Another conflict between Daivadnyas and Vaishyas, in 1348 in Khāṇḍepār or Khaṭegrāma, is mentioned in Khāṇḍepār copperplate. This issue was solved in Gaṇanātha temple in Khāṇḍepār.[20][48]

Diaspora

The Seṭs who had emigrated from Goa for socio-economic reasons during the Goa Inquisition faced many hardships. In places such as Pune they were demeaned and tortured by the Peshwas, had no religious freedom and were divested of all priestly rights. Those who continued to perform religious rites and study the Vedas were punished by methods such as having their tongues and sikhas cut off.[49][50] The Peshwas tried to degrade them to the Shudra level in society so that the Peshwas alone would be called Brahmins.[51]

Documents mention a Gramanya[j] between the Daivadnyas and the Brahmins of Pune or the Puna Joshis. This dispute regarding social status and ritual privilege, lasted from 1822–1825.[52] The opponent Brahmins were against the Daivadnyas administering Vedokta Karmas or Vedic rituals, studying and teaching Vedas, wearing dhoti, folding hands in Namaskar. They urged the Peshwas, and later, the British to impose legal sanctions, such as heavy fines to implement non-observance of Vedokta Karmas, though the later had been always observing the Vedic rites.[53] The Joshis denied their Brahmin claim, allegedly argued that they are not even entitled to Upabrāhmaṇa status which they are bestowed in the 'Śaivāgama.[54] Thus they claimed that latter were not entitled to Vedokta Karmas and should follow only Puraṇokta rites[52] and they were also against the Brahmins who performed Vedic rituals for the Daivadnyas,[53] they incriminated that Daivadnyas have an impurity of descent and have a mixed-caste status or Saṅkara Jāti.[55] Joshis even refused to listen to Sringeri Sharada Peetham Svāmī's order saying Daivadnyas of Bombay are Brahmins and are entitled to Vedokta rites.[55] British issued orders to the Daivadnyas by which the Vedas not be applied for an improper purpose, the purity of the Brahmin caste be preserved[56] and did not impose any restrictions on the Daivadnyas.[55] This dispute almost took a pro-Daivadnya stance in Bombay in 1834,[57] and were ordered to appoint the priests of their own Jāti and not priests of any other caste.[56]

In 1849, the king of Kolhapur, Shahu Maharaj, provided land grants to the Daivadnyas who had migrated to princely states of Kolhapur and Satara and helped them build their hostels for the students pursuing education.[58]

Many families like the Murkuṭes, the Paṭaṇkars, the Seṭs of Karvara and Bhaṭkala kept their tradition alive and excelled in trade, playing a major role in socio-cultural development of the major metropolis of India such as Bombay.[47]

The Daivadnya priests who officiated at the Gokarṇa Mahabaleswara temple were prosecuted in 1927 by the Havyakas of Gokarṇa, who thought they would take over the puja authority at the temple. The case reached the Bombay High Court, which ruled in favour of the Seṭs.[59]

Modern period

Some Goan Daivadnya families migrated to Pune and overseas.Akhīla Bharatiya Daivajña Samajonnati Pariṣat[60] already existed since 1908 for betterment of the kinsmen[47] and was founded by descendants of the native Śeṭs of Mumbai who had settled there within last few centuries.

Few Koṅkaṇe Daivadnya Brahmins have even settled in Vapi, Dharampur, Valsad, Daman and other few places in the state of Gujarat.[61][62]

Similarly, about 3500 Śeṭs migrated to Beṅgalūru city after 1905 from Dakṣiṇa Kannaḍa.[63] Many families have migrated to Mumbai and have founded organisations like Kanara Daivajña Association,[64] Daivajña Śikṣṇa Maṇḍala[65] etc.Śimogā, Cikkamagaluru, Koḍagu, Davaṇgere, Hubballī-Dhārvāḍa districts of Karnataka have a considerable Daivadnya population now.[37]

Śeṭs have also migrated abroad. They are found in the Arab countries[66] and have been migrating overseas in pursuit of higher education and employment for number of years now specially, the United States of America and England.[64] Very few of them are official citizens of Portugal[66] and Kenya.[67] A small fraction of them are also found in Karachi, Lahore[68] Pakistan, but most of them have settled as refugees in Ulhasnagar after partition.[64]

Religion

Their earliest religious beliefs could have been based on a mixture of Brahmanism, Bhagavata religion, sun worship and some folk practices, though it cannot be ascertained to a particular period of time or geographical region. Different schools of Shaivism have existed in Goa and Konkan since ancient times. Similarly, Shaivism was very popular amongst Goans of all walks of life, and was very widely practised. Their religious and cultural beliefs were constantly influenced by other religions such as Jainism, Buddhism and later the Nath sect when the ruling dynasties patronised them. Up to 1476 there was no proper Vaishnavism in Goa.[69]

Deities

Daivadnya Brahmins are predominantly Devi (The mother Goddess) and Shiva worshippers. Panchayatana puja – a concept of worshipping God in any of the five forms, namely Shiva, Devi, Ganesha, Vishnu and Surya, that was propagated by Adi Shankara (8th century) is observed by Daivadnyas today. Daivadnyas worship the Pancayatana deities with Devi or Shiva as the principle deity. A possible Pancayatana set may be: Shantadurga, Shiva, Lakshminarayan (Vishnu with his consort Lakshmi), Ganesha and Surya. Pancayatana may also include guardian deities like Ravalnath, Bhutanath, Kala-Bhairava, Kshetrapala and deities like Gramapurusha.[70]

Few of the Daivadnyas in the coastal track of Karnataka up to the end of Kerala – follow the Vaishnavism. They worship Vishnu and Lakshmi as their prime deities and have established many temples of Vishnu in the form of Lakshminarayan, Krishna, Venkatesha, Narasimha and Vithoba.[71] However, their Kuladevatas (family deities) in Goa are Shakta and Shaiva – the sect centred on Shiva.[2]

Kuladevatas

Their tutelary deities are primarily in the form of the Mother Goddess, though they revere all Vedic, Puranic and folk deities equally.[2]

Ishtadevata

Ishta-devata is a term denoting a worshipper's favourite deity.[72] Ganesha is ishta-devata of all the Śeṭs. Ganesh Chaturthi or Siddhivināyaka Vrata is a major festival of the Daivajñas.

Kalika, Kansarpal, Goa – is worshipped as Ishta-devata by Gomantaka Daivajñas. This temple is more than 800 years old and is located at a distance of around 14 kilometres from Mapusa. It was built by Kadambas and was renovated by a Daivajña minister who was serving Sawant Bhonsale – kings of Sawantwadi, Maharashtra. It is one of the most important temples in the northern part of Goa. The main festivals celebrated in this temple are Śiśirotsava, Navrātrī, Rathasaptamī, Āvalībhojana and Vasantapujā.[13][73][74]

Other Ishta-devata of Daivajñas include Rama, Dattatreya[2] Hanuman,[2] Vithoba of Pandharpur, Hayagriva of Udupi, Mahalakshmi, Krishna, Gayatri, Durgā Parameśvarī, Lakshmi-narayan, Mañjunātha of Dharmasthala and Gokarṇa Mahābaleśvara. Daivajñas maintain several temples in Goa, and about 38 temples in North Canara district of Kanarataka,[75] and many temples in other parts of Karantaka, Maharashtra and few in the state of Kerala.

Daivajñas also honour various saints like Raghavendra Swami, Narasimha Saraswati, Swami Samarth Maharaj, Sai Baba of Shirdi, Sathya Sai Baba and Maṅkipura Svāmī.

Maṭha tradition and Saṃpradāyas

The Śāṅkara or Smārta sect

- Śeṭs of Goa,[76][77] Maharashtra and some parts of Karnataka follow the Smṛtis to abide by the religious rules hence called Smārta i.e. the followers of the Smṛtis. They were followers of Śṛngerī maṭha[6] like Draviḍa Brahmins.[2] Śrī Madhvacārya, the promoter of Dvaita philosophy, during his return journey from North India visited Goa in 1294. Most of them refused to get converted,[78] and very few of them adopted Mādhvadharma.[2][76][79] However Mādhvas, only by tradition they became Bhāgavatas, continued the worship of Śaiva or Śākta deities,[80] Vaiṣṇava Daivajñas are not found in Goa now as they had fled to other states during Inquisition.

- Due to some unavoidable conflicts between the two sects in the community a new maṭha was established in Sri Kshetra Karki, Honnāvara, in North Canara district. The maṭha is called as Jñāneśavarī Pīṭha[81] and is headed by Śrī Śrīmad Bhāratī Tīrtha Svāmī of Śṛṅgerī Śrī Śārada Pīṭha's disciple or Śiṣhya,Śrī Śrīmad Satcidānanda Jñāneśavara Bhāratī Mahāsvāmī for spiritual and religious betterment of the community.[82]

The Vaiṣṇava or Mādhva sect

- The Daivajña diaspora in North Canara, Uḍupi, South Canara and Kerala, who had migrated from Goa due to Arab and Portuguese invasions, were influenced by Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha[83] and adopted Vaiṣṇavism.[2][79][84] History says that a Daivajña named Gopalaśeṭī was sculpting a Gaṇeaśa idol, but it took form of a horse or Hayagrīva, he offered that idol to Vādirāja Tīrtha, the pontiff of Sode maṭha, who later expanded his sphere of influence by taking all the Daivajñas of north Canara into the fold of his Vaiṣṇavism by extending to them dīkṣa and mudra.[2][83][85] This idol of lord Hayagrīva is still worshipped by the pontiffs of Sode maṭha and by their Śeṭ followers.

- The 36th pontiff in the lineage Viśvavallabha Tīrtha Svāmī initiated into Sanyasa by Śrī Viśvottama Tīrtha Svāmī is the present guru of the maṭha and their religious teacher.[86]

Ancestral worship

Daivajñas have a unique system of ancestral worship, the Mūlapuruṣa or the creator of the clan is worshipped in the form of Śiva Liṅga.

Social structure

Gotras or Exogamous family stocks

Most of them share the gotras with Brahmins of the sub-continent. Though Gotra initially meant a cow-pane that symbolised a clan, later usage also implies to lineages of to Vedic seers who were from the above clans, and some were part of the clan by birth yet some had adopted it. Later Gotra was inherited from Guru at the time of Upanayana (which marks the beginning of student-hood), in ancient times, so it is a remnant of Guru-shishya tradition, but since the tradition is no longer followed, during Upanayana ceremony father acts as Guru of his son, so the son inherits his father's gotra.

Surnames and titles

There are no mentions of Daivajñas using surnames in their early history. They have used the honorific title Śeṭī with their name.[70] Names like Nāga Śeṭī,Soma Śeṭī,Viṭhṭhala Śeṭī[91] have been found in the copperplate dating back in the early 12th century which do not bear any surnames. It was only after their exodus from their motherland they started using village names from where their ancestors once hailed.[70] A suffix kār was added to the village or place name which indicates that the person hails from that region.[92] For example, a person hailing from the village of Rāy is known as Rāykār, person from Verṇe as Verṇekār, family from Palan as Palankar and so on. The title Śeṭī or Śeṭ has not fallen into disuse, it is still used as respectful appellation for the elders e.g. Narāyaṇaśeṭ, Sāṃbaśeṭ, Anantaśeṭ. Most of the Daivajñas from Karnataka still affix it to their names[11] and do not use any village names. They have also adopted titles like Rāv and Bhaṭṭa. The maiden name of a woman was changed after marriage and usually affix the honorific title Bāī[93] to their names such as Śāntābāī,Durgābāī; names like Nāgaṃmā and Śivāṃmā are common amongst Canara Daivajñas, but the new generation is too reluctant to use such names.[94]

Other titles include Potdār, Ṭāṅksālī, Vedaka, Daivajña, and Vedapāṭhaka.[95]

Some typical Daivajña surnames are Revankar, Kārekār, Śiroḍkār,Coḍaṇkār, Peḍṇekār, Narvekār, Loṭalīkār, Vernekār, Salkār, Kudtadkār, and Hatkar.[70]

Classification

Subdivisions

Śeṭs were divided according to the place from where they hailed, the maṭha they followed and other criteria.

The Subdivisions of Gomantaka Daivajñas

Until the early 19th century, Goan Śeṭs were divided into three sub-divisions based on their geographical location, but these divisions no longer exist:

- Vāḍkār (from Peḍṇe, Sattarī, Divcal)

- Goyṃkār (from Sāsaṣṭi, Mūrgānv, Tisvāḍī, Bārdes)

- Sauṃdekār (from Phoṇḍā, Kāṇkoṇ, Sāṅge, Kepe)[96]

These sub-divisions never intermarried nor did they accept food from their counterparts.[96]

Diaspora in Maharashtra

There are no prominent distinctions found in Maharashtra, but there are mentions of groups of Śeṭs of Goa, especially from Sāsaṣṭī, Bārdes, Tīsvāḍī, landing in places like Ṭhāṇe,[39] Sāvantvāḍī, Khārepāṭaṇ, Mālvaṇ, Kudāl etc.[97] They are sometimes collectively called as Koṅkaṇastha Daivajñas.[98] Daivajñas from Koṅkaṇa later migrated elsewhere in Maharashtra,[99] and hence they were also known as Koṅkaṇe or Konkane Devajnas as mentioned in old documents.[53]

Previously, Daivajñas from Goa refrained from having matrimonial alliances outside Goa. Today they arrange them with the Daivajñas of Karnataka and Maharashtra.[100]

Śeṭs of Kerala

The emigration of Goan Śeṭs to Kerala dates back to the early 13th century,[101] most of them settled in the port of Koccī. Some of them have migrated from Goa during the later half of the 16th century due to the religious persecution of the Portuguese and settled in places like Quilon, Trichur, Kozhikode, and Kasaragod, along the costal line of Kerala in 1562 AD.

They have their own ancient temple dedicated to Gopalakrishna, perhaps the oldest temple in Fort Cochin.[101]

Culture

Kinship and Saṃskāras, customs

Kinship practices

Konkani people in general though speak Indo-Aryan languages follow Dravidian kinship practices (see Karve, 1965: 25 endnote 3).[102] One's father's brother's children as well as mother's sister's children are considered as brothers and sisters, whereas mother's brother's children and father's sisters children are considered as cousins and potential mates. Cross-cousin marriages are allowed and practiised. Like dravidian people, they refer to their father's sister as mother-in-law or atte, and their mother's brother as father-in-law – mama, and one's husband's mother is generally referred to as mother-maay.[103] Amongst the Śeṭs of Goa the elders, sons-in-law are held with great respect and are revered as Bābū,Bāpla,Tātū,Bāb these words are not used much by other castes in Goa.[1]

Adoption was common in olden days which included a ritual called as Dattak vidhan. Though several restrictions were imposed on adoption. Adoption by an untonsured widow was not valid as per their caste rules.[104] They used to (some still continue to) follow Hindu doctrine theVyavahara Mayukha which prescribes the Hindu law.[105]

Customs

Daivajña people are not so orthodox but they strictly adhere to all the Ṣoḍaśa Saṃskāra or the 16 sacraments, and other brahminical rituals according to the Ṛgveda.[70][106] The Saṃskāras begin to be observed right from the day of conception, but the prenatal sacraments like Garbhadhāna, Puṃsavana, are usually performed as a part of the wedding ceremony nowadays, unlike some 30 years ago these sacraments were held separately after the wedding ceremony at the right time.[107] Sīmantonayana or parting of the hair, called Phulā mālap in Koṅkaṇī or Ḍohāljevaṇ in Marāṭhī, is held in 5th, 7th, 9th months of the pregnancy; the coiffure is adorn with flowers, followed by other rituals. Usually the birth of the first child is supposed to take place in woman's mother's home.[3] After the child is born, ten days of birth pollution or Suyer is observed, by keeping an oil lamp lit for ten days.[70] On the sixth day following childbirth, the goddess Śaṣṭī is worshipped. On the 11th day, a purification Homa is performed. The Nāmakaraṇa or the Bārso, a naming ceremony, is performed on the 12th day.[3] It is sometimes held one month following the child birth if the stars are not favourable. The Karṇavedha or Kān topap ceremony is held on the 12th day in case of a male child, or for a female child, it is held a month after the birth. For Uśṭāvaṇ, Annaprasana or the first feeding ceremony child's maternal uncle feeds the baby with cooked soft rice mixed with milk and sugar. Another similar ritual, Dāntolyo is also performed by the maternal uncle when the baby gets new teeth, on the first birthday of the child. Ceremonies like the first outing or Niṣkrāmaṇa,Jāval or cūdākarṃa i.e. cutting child's hair for first time,Vidyāraṃbha or commencement of studies, are performed as per caste rules.[70]

When the boys grow up, and before they attain the age of 12, Munj or Upanayana is performed with great fanfare.[70] All other sacraments related to it, like Keśānta or the first shave,Vedarambha or, Samāvartana or Soḍ Munj are performed as a part of thread ceremony nowadays. In case of girls(who were always married before attaining puberty some 75–100 years ago), a ceremony associated with a girl's first menstruation was observed in olden days.[108]

The most important sacrament for them is Vivāha,Lagna or the wedding. Various ceremonies held before the actual wedding ceremony are Sākarpuḍo or the betrothal,Devkāre or Devkārya that includes Puṇyāhvācana,Nāndi,Halad,Tel,Uḍid muhurtaSome of their customs are different from any others castes.[1] etc. The actual wedding ceremony is performed as per Ṛgveda.[70]Sīmāntapujā, Kanyādāna, Kaṅkaṇa-bandhana, Maṅgalasutra-bandhana, Saptapadi, Lājahoma, Aṣmārohaṇa, Vāyanadāna form the actual parts of the wedding ceremony. Ceremonies like Gṛhapraveśa, changing the maiden name of the bride, and the puja are followed by some games to be played by the newly wed couple, and the visit to the family deity temple.Pancpartavaṇ or a feast is organised five days after marriage.[1] They strictly observe Gotra exogamy.[109] The custom of dowry in its strict form does not exist any more, but Sālaṅkṛta Kanyādāna with Varadakṣiṇā is followed as a custom. Intercaste marriages are not common in Daivajñas[110]

A widower is and was allowed to remarry. Widow marriages were never practiised in the past though since last half a century due to social reforms widows are permitted to remarry but widow remarriage is still frowned upon by the society. The age for girls for marriage is from 18 to 25 and that for boys is from 25 to 30. Child marriage is absent though girls were married off before attaining puberty, this custom was prevalent till the 19th century.[111]

Their dead are cremated according to the vedic rights, and various Śrāddhas and other Kriyās,Tarpaṇas are performed by the son or any other paternal relative, or in some cases by the son-in-law of the deceased.[70] As per the Vedas, dead infants without teeth must not be cremated,[112] and are supposed to be buried.[70] The body is generally carried to the cremation ground by the son of the deceased and his/her close relatives. Death pollution or Sutaka usually lasts for twelve days.[70] They usually own their own cremation grounds.[70] Women are not allowed in the crematorium.[113] If the deceased was male, his widow was tonsured and strict restrictions were imposed on widows.[114] There was no custom of widow remarriage in the past[115] neither is it very common nowadays[116][117] nor was there any custom of divorce.[115] They pay homage to their ancestors during Mahalaya(Mhall in Konkani) or Pitru Paksha and days like, Amavasya or the new moon day, may be in the form of Shraddha or Kakabali.

Their priests are usually from their own caste, otherwise Karhāḍe priests officiate their ceremonies whom they show much reverence. Daivajñas never used to accept cooked food from other Brahmins.[118] They are still very much reluctant to accept water and cooked food from people belonging to other castes or religions.[100] and untouchability customs still exist.[119]

They celebrate a fish feast after all the major festivals and ceremonies.[1]

Socio-economic background and its history

The traditional occupation of Daivajña people is the jewellery trade. Why this became their occupation is not known. There are no mentions of the Śeṭs practising this occupation in the early history, although they used to make gold and silver images for the temples, which old texts suggest they have inherited this art from the Bhojaks[33] who made idols of the Sun god, hence were also called as Murtikāras. They were well versed in Śilpaśāstra and in Sanskrit hence received royal patronage.[20] Dhume mentions that the Śeṭs also studied medicine, astrology, astronomy[10] in ancient university of Brahmapuri in Goa.[120]

They were renowned for their skills even in the western world and were the first to introduce exquisite jewellery designs to Europe, and were extensively involved in gold, silver, perfumes, black pepper export and even silk, cotton textiles, tobacco[121] and import of horses during Portuguese and pre-Portuguese era.[122] Texts maintain names of many wealthy traders e.g. Virūpa Śeṭī of Coḍaṇe,[122]Āditya Śeṭī of Śivāpura or Śirodā[123] Viṭhṭhala Śeṭī,Dama Śeṭī, who was appointed as an administrator of the Bhatkaṭa port by the Portuguese,[124] and others. Ravala Śeṭī from Caraim who was summoned to Lisbon by the king of Portugal,[125][126] was a collaborator with Afonso de Albuquerque and retained a high office in Goa. Since days of yore their business has been flourishing on the banks of river Mandovi, historical records mention them as prosperous and wealthy traders and business class. These traders, merchants with their fellow artisans, craftsmen had organised themselves into Śreṇīs or guilds,[127] Śreṣṭhīs or the head of the guilds were very wealthy, and made huge donations to the temples, and their guilds also served as local banks and treasuries.[12]

Few of them also worked as interpreters in king's court and were called Dubash, Gaṇa Śeṭī from Loutolim village was in Kadamba rajas court.[128] From the old documents it can be also seen that few of them were involved in politics,[129] and were employed by the kings for their service. Some of them were even associated with salvage operation of the vessels, and sometimes even provided the Portuguese with troops, ships and crew.[130]

They assisted the kings in minting and designing the coins;[20] during Maratha rule some Daivadnya families were given a title of Potdar, which literally means treasurer in Persian, who were in charge of testing the genuineness of the minted coins and their prescribed weight,[131] and played an important role in the revenue system of the Marāṭhas.[132]

The tradition of studying Vedas amongst the Goan Śeṭs does not exist any more,[76] but Daivadnyas from Gokarṇa, Honnavara and many other places in coastal Karnataka and Koṅkaṇa division of Maharashtra have kept this tradition alive. Many of them are priests who offer religious services to the community, very few of them are astrologers and temple priests.[2]

In the Uttara Kannaḍa district of Karnataka, a few families from the poorer section of this community have taken up cultivation to support their livelihood.[133]

Festivals and Vratas

Daivajñas observe all the Hindu festivals but Ganesh Chaturthi, Nag Panchami and Diwali are the most important annual festivals.[100] Other festivals and Vratas observed by them are:

- Saṃvatsarāraṃbha, Saṃvatsar Pāḍvo or Yugādi

- Vaṭa Paurṇimā, Vadāpunav

- Ṛk Śrāvaṇi, Sūtāpunav

- Gokulashtami

- Āditya pujan, Āytārā puja

- Haritālikā Tṛtiyā, Tay or Tayī

- Navratri

- Dasaro, Āvatāñcī pujā

- Bhaubeej

- Tulaśī Lagna

- Ekadashis like Āṣādhī, Kārtikī

- Mālinī Paurṇimā or Mānnī Punav

- Makar Sankranti

- Shigmo

- Holi

- Mahashivratri

- Veṅkaṭapatī Samarādhanā'[134]

- Other rituals in specific months, e.g. Caitragaurī (not observed by Goan Śeṭs) in the month of Chaitra, Maṅgalagaurī, Varadalakṣmī in the month of Shravana (not observed by Goan Śeṭs), Pitru Paksha in the month of Bhadrapada, and some holidays in the months of Kartika and Margashirsha.

The festival of Malini Pournima is exclusively celebrated by very few Śeṭ families of Goa, in honour of Goddess Shakti, (Malini refers to Durga). These families have a unique custom of offering cooked fish to the goddess, in the form of either Kamakshi or Mahamaya.

Several other temple and maţha related festivals like Jātrā, Paryaya, Chaturmas are celebrated with great zeal.

Traditional attire

Daivajña men traditionally wear Dhotīs called Puḍve or Aṅgavastra, which cover them from waist to foot. These are made of cotton and sometimes silk on special occasions and wore Judi or Sadro to cover upper part of their bodies, and a piece of cloth called Uparṇe over the shoulders. They wore turbans and Pagdis, Muṇḍāso, a red velvet cap or Topī was used by the traders and merchants so that they would not be troubled by the Portuguese.[135][136] Men had their ears pierced and wore Bhikbālī, sported Śendī and wore Vibhutī or Sandalwood or Gopīcandana paste on their foreheads. Men were fond of gold jewellery too.[136]

Traditional Daivajña woman wear a nine-yard saree, also known as Kāppad or Cīre in such a way that the back was fully covered.[136] The fashion of wearing a blouse became popular in the 18th century. Ghāgro and a five yards saree was worn by unmarried girls. Women wore gold ornaments on different parts of their bodies (e.g. Ghonṭ, Pāṭlī, Todo, Bājunband, Galesarī, Valesar, Kudī[136]), and wore silver ornaments to decorate their feet (e.g.;Paijaṇ, Salle, Māsolī, Vāle[136]). Gold ornaments were not worn below the waist. Gold is considered a symbol of Agni and is said to keep the evil spirits away. Married women wore Kuṅkuma on their forehead in the shape of a cucumber seed, which is not in vogue any more, and wore Maṅgalsutra, nose rings (a diamond stud,Nath), and toe rings, as a symbol of marriage. Wearing hair in plaits was considered demeaning so they always wore their hair in a bun, and decorated it with flowers and gold ornaments. Widows wore red-coloured nine yards sarees and covered their heads, and sometimes wore Vibhuti on their foreheads.[137]

Languages

Daivadnyas speak Koṅkaṇi and its dialects.[138] Gomantaka Daivadnyas speak a dialect of Koṅkaṇi known as Goan Koṅkaṇi which the Ethnologue recognises as the Gomāntakī dialect, further divided into sub-dialects such as the Bārdescī Bhās or north Goan,Pramāṇa or standard Koṅkaṇī and Sāśṭicī Bhās or south Goan.[111][139] Their Konkani sociolect is different from others and is more closer to the Saraswat dialect.

Daivadnyas in Maharashtra, i.e. Mumbai, Ṭhane, Pune, Kolhapura, Satara, contemporarily speak Maraṭhi. In the Koṅkaṇa region of Maharashtra they speak dialects of Koṅkaṇi such as Malvani, Kudali and others. Daivadnyas in Kanara speak different dialects of Koṅkaṇi, such as Karvari in the Uttara Kannada district and Maṅgluri in the South Canara district.[139]

Almost all of them are bilingual, Goan seṭs can speak Maraṭhi fluently,[100] Canara Seṭs speak Kannaḍa and Tulu outside home,[140] likewise a very small fraction of Keralites can speak Malayalaṃ with an accent, most of them can speak English fluently.[100] Many of them have accepted Maraṭhi/Kannaḍa as their cultural language but noticeably, this has not led to an assimilation of these languages with Koṅkaṇi.[141] Similarly Daivadnyas settled in various parts of Gujarat use the local Gujarati language.[142] Portuguese language is known by many members of older generation of Goans who had done their formal education during the Portuguese rule.

Historians say that the period of migration of Daivajñas and the Kudāldeskārs, from the northern part of India is same, and they settled in Goa in the same period, for this reason members of both the communities speak the same dialect of Koṅkaṇī in Goa.[1][143]

Historically, many scripts have been used writing either Koṅkaṇī or Marāṭhī. An extinct script called as Goykanadi[i] was used by the traders in the early 16th century. The earliest document written in this script is a petition addressed by Ravala Śeṭī to the king of Portugal.[144] Other scripts used include Devanāgarī,Moḍī,[144] Halekannaḍa and Roman script.[144]

Kali Bhasha secret lexicon

Daivajña traders had developed a unique slang called Kalī Bhās, which was used to keep the secrecy of the trade by the traders. Remnants of this jargon are still found in the language used by the Daivajña traders.[145][146][147]

Food habits

Śeṭs refrained from eating all meats except fish.[2] They do not have any social or religious restrictions on consuming fish.[148] Fish is not treated as a meat and are euphemistically called "Sea Vegetable" (Jal Kaay), while oysters are referred to by the name Samudra phala (Sea fruit). Fish from brackish waters is generally preferred to freshwater fish.[149] As these people migrated to different regions of konkan and it's surroundings eating habits has also changed with it. Now most of the urban population consume chicken, mutton as part of their diet. The Vaishnavite and Purohit counterparts are vegetarian.[2]

Arts and music

They do not have their own repertoire of folk songs, but many of them are skilled in singing bhajans, in folk and classical traditions. Until recently every family had a tradition of evening bhajan and prayers with the family members in front of the family gods; a few families have still kept this tradition alive. Children recited Shlokas, Shubhankaroti, Parvacha, as the womenfolk lit the lamp in front of the deity, tulasi and ancestors. Womenfolk were not allowed to sing or dance which was considered demeaning, they do not have any folk songs other than ovis which they hummed while doing household work, some pujas, and other ceremonies such as the naming ceremony, the wedding and the thread ceremony.[150]

Even though they do not have a tradition of folk songs, they have played a significant role in field of Hindustani classical music, drama, arts and literature.[150]

Notable individuals

- Jagannath Shankarshet: philanthropist, reformer, architect of modern Mumbai[151]

- Dwarkanath Madhav Pitale(1882–1928):Marathi writer, Social reformer[152]

- Chandrakala A. Hate: Author, professor, and social worker[153]

- Suresh Haldonkar: classical vocalist, actor[154]

- Pandurang Purushottam Shirodkar: freedom fighter, writer, first speaker of Goa assembly[155]

- Sachin Khedekar: Hindi, Marathi film and TV actor[151]

- Anjali Bhagwat: Rifle shooter[95]

- Sawlaram Haldankar: painter[64]

- Pandit Babanrao Haldankar: classical musicologist[156]

- Subodh Kerkar: installation artist[157]

- Arun Paudwal: Bollywood music composer, singer; Anuradha Paudwal's husband[94]

- Sanjay Narvekar: actor[153]

- Prakashchandra Pandurang Shirodkar: Archaeologist[151]

- Shamrao Madkaikar:Communist and Freedom fighter

- Sudesh Lotlikar: Konkani, Marathi poet and producer/director of documentary films from Goa.[158][159][160][161]

Notes

- ^ ...Śrī Mulapuruṣāne Gauḍadeśāhūna devilā āṇūna ticī sthāpanā chudāmaṇī betāvarīl, Kārai hyā jāgī, Gomatī nadīcyā tīrāvar kelī... (Translation:Mulapuruṣa brought the images of the goddess from the Gauḍadeśa, and installed them in a place called as Kārai on the Chudamani island on the banks of river Gomatī.)

Source:Smaranika:published by Śrī Gajantalakṣmī Ravalnatha Devasthana Mārsel Goa, May 2004 - ^ A study of Comunidade de Caraim was done by Śrī Gajantalakṣmī Ravalnatha Devasthana. This temple used to exist in Caraim until 1510, and was later shifted to Mahem and then to Mārsel, as mentioned in the documents preserved by the temple and the Comunidade de Caraim documents, all the Gauncars of this comunidade were of Daivadnea bramane Casta, and were divided in three vangors. Most of the Gauncars fled in other places to avoid conversions, no Hindu Gauncars are found in Caraim any more, but only two families of Gauncars of the Comunidade de Caraim are found in Caraim now and they belong to the Roman Catholic Brahmin or Bamonn category. Same is the case with Comunidade de Sangolda, and Comunidade de Aldona.

Sources:Smaranika:published by Śrī Gajantalakṣmī Ravalnatha Devasthana Mārsel Goa, May 2004

Ad. Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama Śiroḍkara (Bharatiya samajavighaṭaka jātivarṇa vyavasthā)

Goa: Hindu temples and deities, By Rui Gomes Pereira, Antonio Victor Couto Published by Pereira, 1978, p. 41 - ^ ... The earliest instance of this script we have in a petition addressed by a certain Ravala Śeṭī, most probably a Gaunkar of Caraim in the islands of Goa, to the king of Portugal...

This signature of Ravala Śeṭī in Koṅkaṇī written in Goykānaḍī:

Ravala Śeṭī baraha, which means writing of Ravala Śeṭī

This petition also includes signature of Ravala Śeṭī in Roman script.

Source:History of Goa through Gõykanadi - ^ Grāmaṇya is a crystallisation of conflicts between two castes of individuals belonging to the same caste, and the same group, about observance of certain religious practices vis-a-vis other members of the society or of the particular caste group. There are two types of Grāmaṇyas inter-caste, and intra-caste. (Source:The Satara raj, 1818–1848: a study in history, administration, and culture By Sumitra Kulkarni, Pages: 187,188.)

- ^ Sanskrit Suvarṇakāra, is corrupted to Prākṛta Soṇṇāro from which Koṅkaṇī and Marāṭhī word Sonār is derived. (Source: The Koṅkaṇî language and literature By Joseph Gerson Cunha, p. 18.)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 225 by B. D. Satoskar

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 224, B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- 1 2 3 4 Williams, Monier, "Cologne Digital Sanskrit Dictionaries" (PDF), Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (in Sanskrit and English), retrieved 29 July 2009

- 1 2 "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 221 by B. D. Satoskar, published by Shubhada Publication.

- ↑ Kamat, Pratima (1999), Farar far, Instituto Menezes Bragança, p. xi

- 1 2 Gune, Vithal Trimbak (1979), Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu, 1, Gazetteer Dept, p. 222

- ↑ "Os Bramanes" (Portuguese), by Francisco Luis Gomes

- ↑ Kshirasagara, Narayan Shastri. Vishwabrahmakulothsaha. Pune. p. 139.

- ↑ "Daivagnya Brahmanara Sandhyavandane" by Sri Ramakrishna Narayana Śeṭ. 1980.

- 1 2 Sinai Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986), The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D., p. 257

- 1 2 Census of India, 1961, v. 11, pt. 6, no. 14, India. Office of the Registrar General, 1962, p. 14

- 1 2 3 4 Hidden Hands: Master Builders of Goa By Heta Pandit, Farah Vakil, Homi Bhabha Fellowships Council Published by Heritage Network, 2003, p. 19

- 1 2 "Goa: Hindu Temples and Deities", pp. 121–122. By Rui Pereira Gomes

- ↑ " Goa:Hindu Temples and deities", p. 29 by Rui Pereira Gomes

- ↑ Chapekar, Narayan Govind (1938). िचत्पावन(Chitpavan). Pune: Potdar, Datto Vaman. p. 1.

- ↑ Bharatiya Samajavighataka Jativarna Vyavastha, Kailka Prakashan

- ↑ Maharashtriya Jnanakosha, Part-1, pp. 198–226

- ↑ "Shree Scanda Puran (Sayadri Khandha)" -Ed. Dr. Jarson D. Kunha, Marathi version Ed. By Gajanan shastri Gaytonde, published by Shree Katyani Publication, Mumbai

- ↑ "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 206, B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- 1 2 3 4 "A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagar, By Vithal Raghavendra Mitragotri, Published by Institute Menezes Braganza, 1999, Chapter I, Page 55

- ↑ Mitragotri, Vithal Raghavendra (1999). A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara. Institute Menezes Braganza. pp. 50–54.

- ↑ Kosambī, Dharmānanda, "Dakṣiṇī Sārasvatas", Vividajñāna vistāra (in Marathi), 2 (55): 14

- ↑ Lāḍa, Dr Bhāū Dājī, Indian caste, JAS, p. 54

- ↑ Shastri, (1995) Introduction to the Puranas, New Delhi: Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, pages 118–20

- ↑ Kamat, Pratima (2008). Tarini and Tar-vir, the unique boat deities of Goa. Panjim: Goa Institute for Culture and Research in History (GOINCARH). p. 5. ISBN 978-81-906485-0-9.

- ↑ Israel, Milton; Narendra K. Wagle (1987), Religion and society in Maharashtra

- ↑ Nārāyaṇaśastri Kṣirasāgara, विश्वब्रह्मकुलोत्साह;Viśvabrahmakulotsaha

- ↑ Israel, Milton; Narendra K. Wagle (1987), Religion and society in Maharashtra, p. 159

- 1 2 3 Śiroḍkara, Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama (20 April 1986), "Three:Varṇāñcā bandikhānā", Bhāratiya samājavighaṭaka jātivarṇa vyavasthā (in Marathi) (2 ed.), vasco da Gama: Gomantaka Daivajña Brāhmaṇa Samājotkarṣa Sansthā, pp. 38–56

- ↑ Gomantaka: prakṛti āṇi sanskṛti, Part 1

- ↑ Śiroḍkara, Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama (20 April 1986), "Śākadvipi Maga", Bharatiya samajavighaṭaka jātivarṇa vyavasthā (in Marathi) (1986 ed.), Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal, pp. 78, 79, 80, 81

- ↑ Kosambi, Damodar Dharmananda (2009), Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, ed., The Oxford India Kosambi, New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- 1 2 "A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara" By Vithal Raghavendra Mitragotri Published by Institute Menezes Braganza, 1999, Original from the University of Michigan, Pages: 54, 55

- ↑ "Karnataka State Gazetteer" By Karnataka (India), K. Abhishankar, Sūryanātha Kāmat, Published by Printed by the Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Govt. Press, 1990, p. 251

- ↑ "pt. 6, no. 6", Census of India, 1961, v. 11, Office of the Registrar General, 1962, p. 13

- ↑ Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara (2005). Honorable Jagannath Shankarshet Volume 1 of Hon. Jagannath Shankarshet: Prophet of India's Resurgence and Maker of Modern Bombay, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara. Pradnya-Darshan Prakashan,. pp. 3159 pages (see page 69).

- 1 2 3 "Karnataka State Gazetteer" By Karnataka (India), K. Abhishankar, Sūryanātha Kāmat, Published by Printed by the Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Govt. Press, 1990, p. 254

- ↑ "Journal of Kerala studies" By University of Kerala Published by University of Kerala., 1977, p. 76

- 1 2 Gazetter of Thane region, Gazetter Dept, archived from the original on 10 June 2008, retrieved 22 July 2009

- 1 2 3 The Indian historical review, 30, Indian Council of Historical Research, 2004, p. 38

- ↑ Gune, Vithal Trimbak (1979), Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu, 1, Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept, p. 238

- ↑ Malgonkar, Manohar (2004). Inside Goa. Architecture Autonomous. p. 40. ISBN 978-81-901830-0-0.

- ↑ Christianity in Mangalore, Diocese of Mangalore, archived from the original on 22 June 2008, retrieved 30 July 2008

- ↑ Pinto 1999, p. 124

- ↑ D'Souza, Bento Graciano (1975). Goan society in transition,. p. 37.

- 1 2 "Gomantakatil sūryapan Chatri vād" written by Dr. P. P. Shirodkar, in "Gomant Kalika"(monthly), published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- 1 2 3 Maharashtra State gazetteers, v. 24, pt. 3, Maharashtra (India), Bombay (President)., 1960, pp. 248, 257, 259

- ↑ "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti" by B. D. Satoskar, published by Shubhada Publication

- ↑ Sunthankar, B. R. (1988), Nineteenth century history of Maharashtra, 1, p. 127

- ↑ Patricia, Uberoi (1996), Social reform, sexuality, and the state, p. 6

- ↑ Pawar,, Appasaheb Ganapatrao; Shahu Chhatrapati (Maharaja of Kolhapur), Vilas Adinath Sangave (1978), Rajarshi Shahu Chhatrapati Papers: 1900–1905 A.D.: Vedokta controversy, 3, B. D. Khane, p. 5

- 1 2 Israel, Milton; Narendra K. Wagle (1987), Religion and society in Maharashtra, p. 147

- 1 2 3 Israel, Milton; Narendra K. Wagle (1987), Religion and society in Maharashtra, p. 148

- ↑ Israel, Milton; Narendra K. Wagle (1987), Religion and society in Maharashtra, p. 130

- 1 2 3 Wagle, Narendra K. (1980), Images of Maharashtra, p. 146

- 1 2 Wagle, Narendra K. (1980), Images of Maharashtra, p. 135

- ↑ V. Gupchup, Vijaya (1983), Bombay: social change, 1813–1857, p. 172

- ↑ Journal By Shivaji University, v. 6, Shivaji University, 1973, p. 93

- ↑ "Mahan Daivadnya Sant ani Vibhuti", p. 74, by P. P. Shirodkar, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- ↑ Akhīla Bharatiya Daivajña Samajonnati Pariṣat, retrieved 5 August 2009

- ↑ daivajna mitra, Gujarat, archived from the original on 6 May 2011, retrieved 9 October 2009

- ↑ Daivadnya Sandesh (in Marathi), Mumbai, August 2008, p. 5

- ↑ Karnataka State gazetteer, 19, Gazetteer Dept, 1965, p. 174

- 1 2 3 4 Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (April 2003), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- ↑ Daivajña Śikṣṇa Maṇḍala, retrieved 6 August 2009

- 1 2 Gracias, Fatima da Silva, "Goans away from Goa:Migrations to the middle east", Lusophonies asiatiques, Asiatiques en lusophonies (in English and Portuguese), Centre national de la recherche scientifique (France), Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, p. 428

- ↑ Whiteley, Wilfred Howell, Language in Kenya, Nairobi: Survey of Language Use and Language Teaching in Eastern Africa

- ↑ Pastner, Stephen; Louis Flam (1985), "Goans in Lahore:A study in enthnic identity", Anthropology in Pakistan, pp. 103–107

- ↑ Sinai Dhume, Ananta Ramakrishna (2009). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 BC to 1352 AD. Panaji: Broadway book centre. pp. Chapter 7(pages 291–297). ISBN 9788190571678.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 223, B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- ↑ shree Vadiraja Charitre authored by Gururajacharya

- ↑ V. S. Apte, A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary, p. 250.

- ↑ Official website of Shree Mahamaya Kalika temple

- ↑ "Shree Devi Kalika", Pages-21,60–68, By Shreepadrao P. Madkaikar

- ↑ Kamat, Suryakant (1990), Karnataka State gazetteer, 16, Gazetter Dept, p. 229

- 1 2 3 "People of India: Goa" By Kumar Suresh Singh, Prakashchandra P. Shirodkar, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, Anthropological Survey of India, H. K. Mandal, p. 64

- ↑ "Goa" By Kumar Suresh Singh, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, H. K. Mandal, Anthropological Survey of India, p. 64

- ↑ "Mahan Daivadnya Sant ani Vibhuti" by P. P. Shirodkar, p. 73, published by Kalika Prakashan VishwastMandal

- 1 2 "A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara" By Vithal Raghavendra Mitragotri Published by Institute Menezes Braganza, 1999, Original from the University of Michigan, Pages:108.

- ↑ Mitragotri, Vithal Raghavendra (1999), A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara, Goa University, p. 108

- ↑ Kamat, Suryakant (1984), Karnataka State gazetteer, 3, Gazetter Dept, p. 106

- ↑ "Mahan Daivadnya Sant ani Vibhuti", Pages-72-79 by P. P. Shirodkar, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- 1 2 History of the DVAITA SCHOOL OF VEDANTA and its Literature, p. 542

- ↑ "Mahan Daivadnya Sant ani Vibhuti", p. 73 by P. P. Shirodkar, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- ↑ "Saint Vādirāja Tīrtha's Śrī Rukmiṇīśa Vijaya" By Vādirāja, D. R. Vasudeva Rau

- ↑ About Sodhe Math

- ↑ Pandit, Purushottam (1953), The Early Brahmanical System of Gotra and Pravara (in English and Sanskrit), pp. 31–37

- ↑ "Gotravali" published by "Date Panchang", Date's Almanac Pvt Ltd, Solapur, India

- ↑ "Karnatakatil Rigvedi Daivadnya Brahmananchi Gotravali" published by "Date Panchang", Date's Almanac Pvt Ltd, Solapur, India

- ↑ "Goa" By Kumar Suresh Singh, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, H. K. Mandal, Anthropological Survey of India, p. 65

- ↑ Pereira, Rui Gomes (1978), Goa (in English and Portuguese), p. 179

- ↑ Nāyaka, Puṇḍalīka Nārāyaṇa; Vidya Pai (2002), Upheaval (in English and Konkani), p. 144

- ↑ Karve, Irawati Karmarkar (1953), Kinship organisation in India, p. 108

- 1 2 Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (December 1991), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- 1 2 Daivadnya Sandesh (in Marathi) (November 2000), Mumbai: Akhil Bhartiya Daivadnya Samajonnati Parishad, p. 2

- 1 2 "Bharatiya Samajvighatak Jati Varna Vyavastha" p. 141 by P. P. Shirodkar, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- ↑ आम्ही खारेपाटणचे पाटणकर;Amhi Kharepatanche Patankar:History of Daivajña Raikars settled in Kharepatan (in Marathi)

- ↑ Sociological Bulletin, 1962, Indian Sociological Society, p. 40

- ↑ Irāvati Karve,Maharashtra, land and its people

- 1 2 3 4 5 Singh, Kumar Suresh; Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, H. K. Mandal (1993), Goa, 21, Anthropological Survey of India, p. 68

- 1 2 Menon, Krishnat P. Padmanabha; Jacobus Canter Visscher, T. K. Krishna Menon (1983), History of Kerala, 3, pp. 633, 634

- ↑ Agnihotri, Satish Balram (2000). Sex ratio patterns in the Indian population: a fresh exploration. Sage Publications. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-7619-9392-6.

- ↑ Parkin, Stone, Robert, Linda (2004). Kinship and family: an anthropological reader Blackwell anthologies in social and cultural anthropology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 176–188. ISBN 978-0-631-22999-5.

- ↑ Roy, Sripati Charan (1911), Customs and customary law in British India, Hare press, p. 621

- ↑ Chitaley, D. V. (1948). All India reporter, Volume 2. pp. 129–131.

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh; Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, H. K. Mandal (1993), Goa, 21, Anthropological Survey of India, pp. 66, 67, 68

- ↑ Śiroḍkara, Paṇduraṅga Puruṣottama, Āṭhvaṇī mājhyā kārāvāsācyā – Kālyā nīlyā pāṇācyā (in Marathi), p. 46

- ↑ Gracias, Fatima da Silva, Kaleidoscope of women in Goa, 1510–1961, pp. 49–50

- ↑ Census of India, 1961, 11, India. Office of the Registrar General, 1962, p. 13

- ↑ "Gomant Kalika", articles published in the April 2008 issue by several writers

- 1 2 "People of India: Goa" By Kumar Suresh Singh, Prakashchandra P. Shirodkar, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara, Anthropological Survey of India, H. K. Mandal, p. 65

- ↑ Dvivedi, Bhojaraja, Antyeṣṭi Karma Paddhati (in Hindi), pp. 33–34

- ↑ "Part 6, Issue 14", Census of India, 1961, Volume 11, By India. Office of the Registrar General, 1961, p. 26

- ↑ Gracias, Fatima da Silva, Kaleidoscope of women in Goa, 1510–1961, pp. 76–77

- 1 2 Karnataka State gazetteer By Karnataka (India), 15, Karnataka (India), 1965, p. 254

- ↑ "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 223 by B. D. Satoskar

- ↑ Roy, Sripati Charan (1911), Customs and customary law in British India, p. 587

- ↑ Enthoven, Reginald Edward (1975), The Tribes and Castes of Bombay, 3 (Reprint of the 1920–1922 ed. issued under the orders of the Govt. of Bombay, printed at the Govt. Central Press, Bombay. ed.), p. 343

- ↑ Ghildiyal, Subodh (27 July 2009), Untouchability alive in rural areas: Study, The times of India, p. 1, retrieved 28 July 2009

- ↑ Sinai Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986), The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D., p. 281

- ↑ Veen, Ernst van; Leonard Blussé (2005), Rivalry and conflict, p. 119

- 1 2 Xavier, Ângela Barreto (September 2007), Disquiet on the island: Conversion, conflicts and conformity in sixteenth-century Goa, Indian Economic & Social History Review, vol. 44, pp. 269–295

- ↑ De Souza, Teotonio R. (1990), Goa Through the Ages: An economic history, Concept Publishing Company, p. 119, ISBN 978-81-7022-259-0

- ↑ Shastry, Bhagamandala Seetharama; Charles J. Borges (2000), Goa-Kanara Portuguese relations, 1498–1763 By, pp. 19, 20

- ↑ dos Santos, R. (1954), A India Portugueasa e as artes em Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, p. 9

- ↑ "The Portuguese empire, 1415–1808" By A. J. R. Russell-Wood, Page 105

- ↑ Purabhilekh-puratatva By Goa, Daman and Diu (India)., 5, Directorate of Archives, Archaeology, and Museum, 1987, pp. 11, 12, 13, 17

- ↑ "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-2, p. 562, by B. D. Satoskar, published by Shubhada Publication

- ↑ Dikshit, Giri S; A. V. Narasimha Murthy, K. V. Ramesh (1987), Giridharaśrī By, p. 199

- ↑ The Indian historical review, 30, Indian Council of Historical Research, 2004, p. 38

- ↑ The Journal of the administrative sciences, v. 24–25, Patna University. Institute of Public Administration, Patna University, 1979, p. 96

- ↑ Joshi, P. M.; A. Rā Kulakarṇī, M. A. Nayeem, Teotonio R. De Souza, Mediaeval Deccan history, p. 303

- ↑ "pt. 6, no.36", Census of India, 1961, v. 11, Office of the Registrar General, 1962, p. 13

- ↑ Gomant Kalika (in Marathi), Margao, Goa: Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- ↑ Gune, Vithal Trimbak (1979), Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu, 1, Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept, p. 254

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Gomantak Pranruti and Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 381 by B. D. Satoskar

- ↑ Different articles published in "Gomant Kalika", published by Kalika Prakashan

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Konkani(ISO 639: kok), Ethnologue

- 1 2 Ethnologue report for Konkani, Goan (ISO 639-3: gom), Ethnologue

- ↑ Padmanabha, P. (1973), Census of India, 1971, India. Office of the Registrar General, pp. 107, 111, 112, 323,

- ↑ Abbi, Anvita; R. S. Gupta, Ayesha Kidwai (4–6 January 1997), Linguistic structure and language dynamics in South Asia, Mahadev K. Verma, p. 18

- ↑ Gujarati being used by the migrant Daivajnas (in English, Gujarati, and Marathi), Gujarat, archived from the original on 6 May 2011, retrieved 9 October 2009

- ↑ Article written by Devakinanadan Daivadnya, daily "Rashtramat" published from Goa, 17 August 1974, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Ghantkar, Gajanana (1993), History of Goa through Gõykanadi script (in English, Konkani, Marathi, and Kannada), pp. Page x

- ↑ "Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti", Part-1, p. 226, by B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- ↑ "Gomant Kalika"(monthly), April 2004, published by Kalika Prakashan Vishwast Mandal

- ↑ "Mahan Daivadnya Sant ani Vibhuti", p. 50, By P. P Shirodkar, Kalika Prakashan

- ↑ India. Office of the Registrar General (1967). Census of India, 1961, Volume 11, Part 6, Issue 6. Manager of Publications,. p. 21.

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh; Prakashchandra P. Shirodkar, Pra. Pā Śiroḍakara (1993), People of India: Goa, Anthropological Survey of India, H. K. Mandal, p. xiv

- 1 2 Shirodkar, Dr Prakashchandra; H. K. Mandal, Anthropological Survey of India (1993), Kumar Suresh Singh, ed., Goa Volume 21 of People of India, Kumar Suresh Singh Volume 21 of States series, Popular Prakashan, pp. 63, 64, ISBN 978-81-7154-760-9

- 1 2 3 Daivadnya Sandesh (in Marathi) (October 2008), Mumbai: Akhil Bhartiya Daivadnya Samajonnati Parishad, p. 2

- ↑ Daivadnya Sandesh (in Marathi), 1 September 2009, p. 2

- 1 2 Daivadnya Sandesh (in Marathi) (September 2008), Mumbai: Akhil Bhartiya Daivadnya Samajonnati Parishad, p. 2

- ↑ Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (April 2004), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- ↑ Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (May 2000), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- ↑ Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (August 2003), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- ↑ Gomant Kalika (in Marathi) (December 2007), Magao, Goa: Kalika prakashan vishwast mandal

- ↑ Saradesāya, Manohararāya (2000-01-01). A History of Konkani Literature: From 1500 to 1992. p. 180. ISBN 8172016646.

- ↑ "'Eastern and Western Writers Meet' Today". Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Tradition Of Diwali Literary Supplements". Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ "Reviving cultural traditions". Retrieved 19 January 2014.

Further reading

- Gomes, Rui Pereira; Couto, Antonio Victor (1978). Goa:Hindu Temples and deities.

- Gomes, Rui Pereira; Couto, Antonio Victor (1981). Goa.

- Ranganathan, Murali; Gyan Prakash (2009). Govind Narayan's Mumbai. Anthem Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-1-84331-305-2.

- Saldanha, Jerome A. Origin and growth of Konkani or Goan communities and language.

- Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna Sinai. The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D.

- Goa (1979). Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu: district gazetter.

- Ghurye, Govind Sadashiv (1993). Caste and race in India (5 ed.). p. 493.

- Karve, Irawati (1961). Hindu society (2 ed.). p. 171.

- De, Souza; Carmo:borges, Charles. The Village Communities. A Historical and legal Perspective.

- Charles J. Borges; Helmut Feldmann (1997). Goa and Portugal. p. 319.

- Thākare, Keśava Sitārāma (1919). Grāmaṇyācā sādyanta itihāsa arthāta nokarśāhīce banḍa (in Marathi). Mumbai.

- Joshi, Mahadevshastri (1979). Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosh (Marathi: भारतीय संस्कृती कोश). Bharatiya Sanskriti Kosh Mandal.

- Dias, Giselle (May 2007). A search for an identity Catholic Goans – How they fit in a predominantly Hindu India (PDF, 66 KB). Goan Association of Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Based on various books). Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- "Genetics of Castes and Tribes of India:Indian Population Milieu" by M. K. Bhasin, Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, IndiaGenetics of Castes and Tribes of India:Indian Population Milieu (PDF).

- The Sixteen Samskaras Part-I (PDF). 8 August 2003. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

External links

| Look up Daivajna in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Community homepage

- Daivajña Community

- Daivajña Samajonnati Parishat

- Daivajña Shikshan Mandal

- Daivajña Samaj in Gujarat

- Official website for Karki Matha