David Rittenhouse

| David Rittenhouse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

April 8, 1732 Paper Mill Run, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

June 26, 1796 (aged 64) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation |

Astronomer Inventor Mathematician |

David Rittenhouse (April 8, 1732 – June 26, 1796) was a renowned American astronomer, inventor, clockmaker, mathematician, surveyor, scientific instrument craftsman and public official. Rittenhouse was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the first director of the United States Mint.

Biography

Rittenhouse was born in a small village within Philadelphia called Rittenhousetown. This village is located near Germantown, along the stream Paper Mill Run, which is a tiny tributary of the Wissahickon Creek.

When his uncle died, Rittenhouse inherited his uncle's set of carpentry tools and instructional books. Using his uncle's tools, he began a career as an inventor. Also at a young age, Rittenhouse showed a high level of intelligence by creating a working scale model of his grandfather's paper mill. He built other scale models in his youth, like a working waterwheel. He was self-taught from his family's books, never attended elementary school, and showed great ability in science and mathematics. When Rittenhouse was 13 years of age, he had mastered Isaac Newton's laws of motion and gravity.

When he was 19, he started a scientific instrument shop at his father's farm in what is now Valley Forge Medical Center & Hospital, located in East Norriton Township, Pennsylvania. His skill with instruments, particularly clocks, led him to construct two orreries (scale models of the solar system), the first for The College of New Jersey (now known as Princeton University), the second for the College of Philadelphia (now known as the University of Pennsylvania). Rittenhouse was prevailed upon to construct the second orrery by his friend, the Reverend William Smith, the first provost of the College of Philadelphia, who was upset that Rittenhouse would deliver such a device to a college located in the rural area of New Jersey, rather than in Philadelphia, which was seeking to be one of the important centers of the 18th century enlightenment and for the study of "natural philosophy" such as astronomy. Both of these orreries still exist, with each being held by their original recipients: one in the library of the University of Pennsylvania and the other at Peyton Hall of Princeton University.

Clubs and societies

Astronomers who had been studying the planet Venus chose Rittenhouse to study the transit path of Venus in 1769 and its atmosphere. Rittenhouse was the perfect person to study the mysterious planet, as he had a personal observatory on his family farm. "His telescope, which he made himself, utilized grating intervals and spider threads on the focus of the telescope." His telescope is very similar to some modern-day telescopes. Rittenhouse served on the American Astronomical Society, and this was another factor in being chosen to study Venus. Throughout his life he had the honour to serve in many different clubs and committees.

In 1768 he was elected to membership in the American Philosophical Society. He served as librarian, secretary, and after Benjamin Franklin's death, he became Vice president.[1] Following the death of Franklin in 1790, Rittenhouse served as president of the American Philosophical Society until 1796.[2][3] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1782.[4]

Another one of his interests was the Royal Society of London of which he was a member. It was very rare for an American to be a member of this exclusive British society.

In 1786 Rittenhouse built a new Georgian-style house on the corner of 4th and Arch streets in Philadelphia, next to an octagonal observatory he had already built. At this house, he maintained a Wednesday evening salon meeting with Benjamin Franklin, Francis Hopkinson, Pierre Eugene du Simitiere and others. Thomas Jefferson wrote that he would rather attend one of these meetings "than spend a whole week in Paris."[5]

Family

David Rittenhouse was married twice. He married Eleanor Coulston February 20, 1766, and they had two daughters: Elizabeth (born 1767) and Ester (born 1769). Eleanor died February 23, 1771, at age 35 from complications during the birth of their third baby, who died at birth.

David married his second wife Hannah Jacobs on December 31, 1772. They had an unnamed baby, who died at birth in late 1773. Hannah survived David by more than three years, dying in late 1799.

David's grandson (son of Ester) was named David Rittenhouse Waters.[6]

Notable contributions to the United States

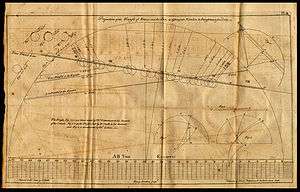

David Rittenhouse made many breakthroughs during his life, which were great contributions to the U.S. During the first part of his career he was a surveyor for Great Britain, and later served in the Pennsylvania government. His 1763–1764 survey of the Delaware-Pennsylvania border was a 12-mile circle about the Court House in New Castle, Delaware, to define the northern border of Delaware. Rittenhouse's work was so precise and well-documented that it was incorporated without modification into Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon's survey of the Pennsylvania-Maryland border.

Later Rittenhouse helped establish the boundaries of several other states and commonwealths both before and after the Independence, including the boundaries between New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania. In 1763 Mason and Dixon began a survey of the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, but this work was interrupted in 1767. In 1784 Rittenhouse and Andrew Ellicott completed this survey of the Mason-Dixon line to the southwest corner of Pennsylvania. When Rittenhouse's work as a surveyor ended, he resumed his scientific interests.

Transit of Venus

In 1768, the same year that he became a member of the American Philosophical Society, Rittenhouse announced plans to observe a pending transit of Venus across the Sun from several locations. The American Philosophical Society persuaded the legislature to grant £100 towards the purchase of new telescopes, and members volunteered to man half of the 22 telescope stations when the event arrived.[7][8]

The transit of Venus occurred on 3 June 1769. Rittenhouse's great excitement at observing the infrequently occurring transit of Venus (for which he had prepared for a year) resulted in his fainting during the observation. In addition to the work involved in the preparations, he had also been ill the week before the transit. Lying on his back beneath the telescope, trained at the afternoon sun, he regained consciousness after a few minutes and continued his observations. His account of the transit, published in the American Philosophical Society's Transactions, does not mention his fainting, though it is otherwise meticulous in its record and documented.

Rittenhouse used the observations to calculate the distance from Earth to the Sun to be 93-million miles.[7] (This is the approximate average distance between Earth and the Sun.) The published report of the transit was hailed by European scientists, and Rittenhouse would correspond with famous contemporary astronomers, such as Jérôme Lalande and Franz Xaver von Zach.[7]

Orrery

In 1770 Rittenhouse completed an advanced orrery. In recognition of the achievement, the College of New Jersey granted Rittenhouse an honorary degree.[8] The college then acquired ownership of the orrery. Rittenhouse made a new, more advanced model which remained in Philadelphia. The State of Pennsylvania paid Rittenhouse £300 as a tribute for his achievement.[9] One of Rittenhouse's hands or helpers with the project[10] was Henry Voigt, the clockmaker and Chief Coiner under Rittenhouse at the mint. Voigt later repaired the orrery in 1806 and was an earlier co-inventor of the first practical steamboat with John Fitch.

Rittenhouse was admired by many colonial Americans and scientists, including Dr. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson,[9] and John Adams.[8] On February 24, 1775, Rittenhouse delivered a lecture on the history of astronomy to the American Philosophical Society, in which he linked the structure of nature to the rights of man, liberty and self-government.[9][11] Rittenhouse also used the occasion to decry slavery.[12] So impressed were those in attendance that the American Philosophical Society commissioned the speech to be printed and distributed to delegates of the Second Continental Congress when they arrived in 1776.[12][13]

United States Mint

David Rittenhouse was treasurer of Pennsylvania from 1777 to 1789, and with these skills and the help of George Washington, he became the first director of the United States Mint.[14] On April 2, 1792, the United States Mint opened its doors, but would not produce coins for almost four months. Rittenhouse believed that the design of the coin made the coin a piece of artwork. The first coins were made from flatware that was provided by Washington himself on the morning of July 30, 1792. The coins were hand-struck by Rittenhouse, to test the new equipment, and were given to Washington as a token of appreciation for his contributions to making the United States Mint a reality. The coin design had not been approved by Congress. Coin production on a large scale did not begin until 1793. Rittenhouse resigned from the Mint on June 30, 1795, due to poor health. In 1871 Congress approved a commemorative medal in his honor.

Additional contributions

In 1781 Rittenhouse became the first American to sight Uranus.[7]

In 1785 Rittenhouse made perhaps the first diffraction grating using 50 hairs between two finely threaded screws, with an approximate spacing of about 100 lines per inch.[15] This was roughly the same technique that Joseph von Fraunhofer used in 1821 for his wire diffraction grating.

Notable events

Other notable events in Rittenhouse's life include:

- 1763–1764 Worked on the boundary survey of Pennsylvania and Maryland

- 1767 Granted an honorary master's degree from the College of Philadelphia (later University of Pennsylvania)

- 1768 Discovered the atmosphere of Venus

- 1769 Observed the transit of Venus

- 1770 Came to Philadelphia

- 1775 Engineer of the Committee of Safety

- 1779–1782 Professor of Astronomy in the University of the State of Pennsylvania, now known simply as the University of Pennsylvania

- 1780–1782 Vice-Provost

- 1782–1796 Trustee

- 1779–1787 Treasurer of Pennsylvania

- 1784 Completed the survey of the Mason-Dixon line

- 1791–1796 President of the American Philosophical Society

- 1792–1795 First Director of the United States Mint

- 1793 He was a founder of the Democratic-Republican Societies in Philadelphia.

Jefferson's Notes on Virginia

In his book Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson listed Rittenhouse alongside Benjamin Franklin and George Washington as examples of New World genius when disputing French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc Comte de Buffon's claim that the environment and climate of North America had stunted the intellect of peoples living there both native and European.[16]

Tributes to David Rittenhouse

- Rittenhouse Crater is a lunar crater named for David Rittenhouse.

- In 1825, one of William Penn's original squares in Philadelphia, called 'Southwest Square' (because of its place in the original city plan) was renamed Rittenhouse Square in David Rittenhouse's honor.

- To the west of Rittenhouse Square, on Walnut Street, the University of Pennsylvania houses its Physics and Mathematics departments in the David Rittenhouse Laboratory.

- One admirer and colleague of Rittenhouse, Francis Hopkinson, was on the Navy Board that wrote the Flag Act of 1777, which defined the Flag of the United States of America and explained the blue field of stars as a representation of "a new constellation." This is thought by some to be a direct tribute to Rittenhouse. Biographer Brooke Hindle wrote, "Few admired Rittenhouse more unrestrainedly than Francis Hopkinson."[5]

- David Rittenhouse Junior High School, Norristown, Pennsylvania; listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.[17]

- Rittenhouse's nephew (and American Philosophical Society member) William Barton published a biography, Memoirs of the life of David Rittenhouse.[18]

References

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin named Rittenhouse in his will, leaving him a telescope in return for the use of Rittenhouse's observatory. See Franklin's will on WikiSource..

- ↑ David Rittenhouse (1732–1796). University of Pennsylvania

- ↑ UNDAUNTED: David Rittenhouse (1732–1796). American Philosophical Society

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter R" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- 1 2 Keim, 43

- ↑ Rittenhouse Newsletter Vol 1–5, 1989

- 1 2 3 4 Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Revolutionary America, 1763–1800. New York: Facts On File, Inc. p. 289. ISBN 0-8160-2528-2.

- 1 2 3 Keim, 40

- 1 2 3 Keim, 41

- ↑ The Rittenhouse orrery: Princeton's Eighteenth-century Planetarium, 1767–1954. A commentary on an exhibition held in the Princeton University Library. Howard Crosby Rice. Princeton University Library, 1954. p.34

- ↑ Original text available from Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Keim, 42

- ↑ Richard Smith's Diary, Letters of Delegates to Congress: Volume: 3 January 1, 1776 – May 15, 1776. From the Library of Congress. Website accessed June 29, 2009.

- ↑ History of the Mint from usmint.gov. Website accessed 11 June 2009

- ↑ See:

- "An optical problem, proposed by Mr. Hopkinson, and solved by Mr. Rittenhouse," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 2, pp. 201–206 (1786).

- Thomas D. Cope (1932) "The Rittenhouse diffraction grating". Reprinted in: David Rittenhouse, The Scientific Writings of David Rittenhouse, Brooke Hindle, ed. (New York, New York: Arno Press, 1980), pp. 377–382. (A reproduction of Rittenhouse's letter re his diffraction grating appears on pages 369–374.)

- ↑ Daniel Patterson, Roger Thompson (2008). Early American Nature Writers: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Westport,CT: Greenwood Press.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Available online at Google Books

Sources

- Keim, Kevin; Keim, Peter (2007). A Grand Old Flag. A History of the United States through Its Flags. New York, New York: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7566-2847-5.

Further reading

- Greenslade, Thomas B., "Wire Diffraction Gratings," The Physics Teacher, February 2004. Volume 42 Issue 2, pp. 76–77.

External links

Quotations related to David Rittenhouse at Wikiquote

Quotations related to David Rittenhouse at Wikiquote- Historic RittenhouseTown, Birthplace of N. American Paper & David Rittenhouse

- Biography and portrait at the University of Pennsylvania

- History of the University of Pennsylvania Orrery

- History of the Princeton Orrery

- The Rittenhouse Astronomical Society

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "David Rittenhouse", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- David Rittenhouse at Find a Grave

"Rittenhouse, David". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Rittenhouse, David". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. "Rittenhouse, David". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Rittenhouse, David". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.- David Rittenhouse at everything2.com

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by new office |

Treasurer of Pennsylvania 1777–1789 |

Succeeded by Christian Febiger |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by New title |

1st Director of the United States Mint 1792–1795 |

Succeeded by Henry William de Saussure |