Malays (ethnic group)

A Malay couple in traditional attire after their akad nikah (marriage solemnisation) ceremony. The groom is wearing a baju melayu paired with songkok and songket, while the bride is clad in baju kurung with a tudung. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (c. 24 million) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Native area | . |

| 5,365,399[3] | |

| 1,964,384[4] | |

| 653,449[5] | |

| Diaspora | . |

| ~200,000[6]note | |

| 40,189[7]note | |

| 33,183[8] | |

| ~33,000[9] | |

| ~27,000[10] | |

| Languages | |

|

Official:

Others:

| |

| Religion | |

|

All | |

|

^ note: Highly naturalised population of mixed origins, but using the 'Malay' identity | |

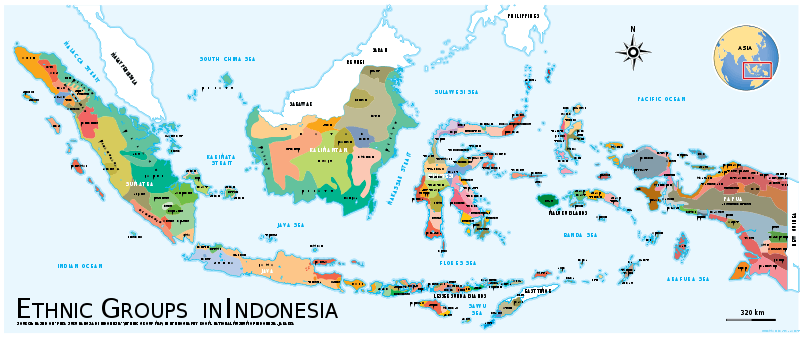

Malays (Malay: Orang Melayu, Jawi: اورڠ ملايو) are an ethnic group of Austronesian peoples predominantly inhabiting the Malay Peninsula, eastern Sumatra and coastal Borneo, as well as the smaller islands which lie between these locations — areas that are collectively known as the Malay world. These locations today are part of the modern nations of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei, and southern Thailand.

There is considerable genetic, linguistic, cultural, and social diversity among the many Malay subgroups, mainly due to hundreds of years of immigration and assimilation of various regional ethnicity and tribes within Maritime Southeast Asia. Historically, the Malay population is descended primarily from the earlier Malayic-speaking Austronesians and Austroasiatic tribes who founded several ancient maritime trading states and kingdoms, notably Brunei, Kedah, Langkasuka, Gangga Negara, Chi Tu, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Pahang, Melayu and Srivijaya[11][12]

The advent of the Malacca Sultanate in the 15th century triggered a major revolution in Malay history, the significance of which lies in its far-reaching political and cultural legacy. Common definitive markers of a Malayness - the religion of Islam, the Malay language and traditions - are thought to have been promulgated during this era, resulting in the ethnogenesis of the Malay as a major ethnoreligious group in the region.[13] In literature, architecture, culinary traditions, traditional dress, performing arts, martial arts, and royal court traditions, Malacca set a standard that later Malay sultanates emulated. The golden age of the Malay sultanates in the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra and Borneo saw many of their inhabitants, particularly from various tribal communities like the Batak, Dayak, Orang Asli and the Orang laut become subject to Islamisation and Malayisation.[14] Today, some Malays have recent forbears from other parts of Maritime Southeast Asia, termed as anak dagang ("traders") and who predominantly consist of Javanese people, Bugis, Minangkabau people and Acehnese peoples, while some are also descended from more recent immigrants from other countries.[15]

Throughout their history, the Malays have been known as a coastal-trading community with fluid cultural characteristics.[16][17] They absorbed, shared and transmitted numerous cultural features of other local ethnic groups, such as those of Minang, Acehnese, and to some degree Javanese culture; however Malay culture differs by being more overtly Islamic than the multi-religious Javanese culture. Ethnic Malays are also the major source of the ethnocultural development of the related Betawi, Banjar, Cape Malay, Peranakan and Sri Lankan Malay cultures, as well as the development of Malay trade and creole languages like Ambonese Malay, Baba Malay, the Betawi language and Manado Malay.

Etymology

The epic literature, the Malay Annals, associates the etymological origin of "Melayu" to Sungai Melayu ('Melayu river') in Sumatra. The term is thought to be derived from the Malay word melaju, a combination of the verbal prefix 'me' and the root word 'laju', meaning "to accelerate", used to describe the accelerating strong current of the river.[18]

The word "Melayu" as an ethnonym, to allude to a clearly different ethnological cluster, is assumed to have been made fashionable throughout the integration of the Malacca Sultanate as a regional power in the 15th century. It was applied to report the social partialities of the Malaccans as opposed to foreigners as of the similar area, especially the Javanese and Thais[19] This is evidenced from the early 16th century Malay word-list by Antonio Pigafetta who joined the Magellan's circumnavigation, that made a reference to how the phrase chiara Malaiu ('Malay ways') was used in the maritime Southeast Asia, to refer to the al parlare de Malaea (Italian for "to speak of Malacca").[20]

The English term "Malay" was adopted via the Dutch word Malayo, itself derived from Portuguese: Malaio, which originates from the original Malay word, Melayu.

Prior to the 15th century, the term "Melayu" and its similar-sounding variants appear to apply as an old toponym to the Strait of Malacca region in general.[21]

- Malaya Dwipa, "Malaya Dvipa", is described in chapter 48, Vayu Purana as one of the provinces in the eastern sea that was full of gold and silver. Some scholars equate the term with Sumatra,[22] but several Indian scholars believe the term should refer to the mountainous Malay peninsula, while Sumatra is more correctly associated with Suvarnadvipa.[23][24][25][26][27]

- Maleu-kolon - appeared in Ptolemy's work, Geographia.[28]

- Mo-lo-yu - mentioned by Yijing, a Tang dynasty Chinese Buddhist monk who visited the Southeast Asia in 688–695. According to Yijing, the Mo-Lo-Yu kingdom was located in a distance of 15 day sail from Bogha (Palembang), the capital of Sribhoga (Srivijaya). It took a 15-day sail as well to reach Ka-Cha (Kedah) from Mo-lo-yu; therefore, it can be reasoned that Mo-Lo-Yu would lie halfway between the two places.[29] A popular theory relates Mo-Lo-Yu with the Jambi in Sumatra,[30] however the geographical location of Jambi contradicts with Yi Jing's description of a "half way sail between Ka-Cha (Kedah) and Bogha (Palembang)". In the later Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) and Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the word Ma-La-Yu was mentioned often in Chinese historical texts - with changes in spelling due to the time span between the dynasties - to refer to a nation near the southern sea. Among the terms used was "Bok-la-yu", "Mok-la-yu" (木剌由), Ma-li-yu-er (麻里予兒), Oo-lai-yu (巫来由) - traced from the written source of monk Xuanzang), and Wu-lai-yu (無来由).

- Malayur - inscribed on the south wall of the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tamil Nadu. It was described as a kingdom that had "a strong mountain for its rampart" in Malay peninsula, that fell to the Chola invaders during Rajendra Chola I's campaign in the 11th century.

- Bhūmi Mālayu - (literally "Land of Malayu"), a transcription from Padang Roco Inscription dated 1286 CE by Slamet Muljana.[31] The term is associated with Dharmasraya kingdom.

- Ma-li-yu-er - mentioned in the chronicle of Yuan Dynasty, referring to a nation of Malay peninsula that faced the southward expansion of Sukhothai Kingdom, during the reign of Ram Khamhaeng.[32] The chronicle stated: "..Animosity occurred between Siam and Ma-li-yu-er with both killing each other ...". In response to the Sukhothai's action, a Chinese envoy went to the Ram Khamhaeng's court in 1295 bearing an imperial decree: "Keep your promise and do no evil to Ma-li-yu-er".[33]

- Malauir - mentioned in Marco Polo's account as a kingdom located in the Malay peninsula,[34][35] possibly similar to the one mentioned in Yuan chronicle.

- Malayapura - (literally "city of Malaya" or "fortress of Malaya"), inscribed on the Amoghapasa inscription dated 1347 CE. The term was used by Adityawarman to refer to Dharmasraya.The word Malay refer to Mountain and Pura refer to Country in Pali Language.

Other the Javanese word mlayu (to run) derived from mlaku (to walk or to travel), or the Malay term melaju (to steadily accelerate), to refer the high mobility and migratory nature of its people, however these suggestions remain as popular beliefs without corroborating evidence.

Origins

Proto-Malay models

Also known as Melayu asli (aboriginal Malays) or Melayu purba (ancient Malays), the Proto-Malays are of Austronesian origin and thought to have migrated to the Malay archipelago in a long series of migrations between 2500 and 1500 BC.[36] The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Early History, has pointed out a total of three theories of the origin of Malays:

- The Yunnan theory, Mekong river migration (published in 1889) - The theory of Proto-Malays originating from Yunnan is supported by R.H Geldern, J.H.C Kern, J.R Foster, J.R Logen, Slamet Muljana and Asmah Haji Omar. Other evidence that supports this theory include: stone tools found in the Malay Archipelago are analogous to Central Asian tools, the similarity of Malay customs and Assam customs.

- The New Guinea theory (published in 1965) - The proto-Malays are believed to be seafarers knowledgeable in oceanography and possessing agricultural skills. They moved great distances from island to island as far apart as modern day New Zealand and Madagascar, and they served as navigation guides, crew and labour to Indian, Arab, Persian and Chinese traders for nearly 2000 years. Over the years they settled at various places and adopted various cultures and religions.

- The Taiwan theory (published in 1997) - The migration of a certain group of Southern Chinese occurred 6,000 years ago, some moved to Taiwan (today's Taiwanese aborigines are their descendants), then to the Philippines and later to Borneo (roughly 4,500 years ago) (today's Dayak and other groups). These ancient people also split with some heading to Sulawesi and others progressing into Java, and Sumatra, all of which now speak languages that belong to the Austronesian Language family. The final migration was to the Malay Peninsula roughly 3,000 years ago. A sub-group from Borneo moved to Champa in modern-day Central and South Vietnam roughly 4,500 years ago. There are also traces of the Dong Son and Hoabinhian migration from Vietnam and Cambodia. All these groups share DNA and linguistic origins traceable to the island that is today Taiwan, and the ancestors of these ancient people are traceable to southern China.[37]

Deutero-Malays

The Deutero-Malays are Iron Age people descended partly from the subsequent Austronesian peoples who came equipped with more advanced farming techniques and new knowledge of metals.[38] They are kindred but more Mongolised and greatly distinguished from the Proto-Malays which have shorter stature, darker skin, slightly higher frequency of wavy hair, much higher percentage of dolichocephaly and a markedly lower frequency of the epicanthic fold.[38] The Deutero-Malay settlers were not nomadic compared to their predecessors, instead they settled and established kampungs which serve as the main units in the society. These kampungs were normally situated on the riverbanks or coastal areas and generally self-sufficient in food and other necessities. By the end of the last century BC, these kampungs beginning to engage in some trade with the outside world.[39] The Deutero-Malays are considered the direct ancestors of present-day Malay people.[40] Notable Proto-Malays of today are Moken, Jakun, Orang Kuala, Temuan and Orang Kanaq.[41]

Expansion from Sundaland model

A more recent theory holds that rather than being populated by expansion from the mainland, the Ice Age populations of the Malay peninsula, neighbouring Indonesian archipelago, and the then-exposed continental shelf (Sundaland) instead developed locally from the first human settlers and expanded to the mainland. Proponents of this theory hold that this expansion gives a far more parsimonious explanation of the linguistic, archaeological, and anthropological evidence than earlier models, particularly the Taiwan model.[42] This theory also draws support from recent genetic evidence by Human Genome Organisation suggesting that the primary peopling of Asia occurred in a single migration through Southeast Asia; this route is held to be the modern Malay area and that the diversity in the area developed mainly in-place without requiring major migrations from the mainland. The expansion itself may have been driven by rising sea levels at the end of the Ice Age.[43][44]

Proponent Stephen Oppenheimer has further theorised that the expansion of peoples occurred in three rapid surges due to rising sea levels at the end of the Ice Age, and that this diaspora spread the peoples and their associated cultures, myths, and technologies not just to mainland Southeast Asia, but as far as India, the Near East, and the Mediterranean. Reviewers have found his proposals for the original settlement and dispersal worthy of further study, but have been sceptical of his more diffusionist claims.[45][46][47]

History

Indian influence

There is no definite evidence which dates the first Indian voyages across the Bay of Bengal but conservative estimates place the earliest arrivals on Malay shores at least 2,000 years ago. The discovery of jetty remains, iron smelting sites, and a clay brick monument dating back to 110 CE in the Bujang Valley, shows that a maritime trading route with South Indian Tamil kingdoms was already established since the second century.[48]

The growth of trade with India brought coastal people in much of maritime Southeast Asia into contact with the major religions of Hinduism and Buddhism. Throughout this area a most profound in influence has been exerted by India which seems to have introduced into it architecture, sculpture, writing, monarchy, religion, iron, cotton and a host of elements of higher culture. Indian religions, cultural traditions and Sanskrit began to spread across the land. Hindu temples were built in the Indian style, local kings began referring to themselves as "raja" and more desirable aspects of Indian government were adopted.[49]

The beginning of the Common Era saw the rise of Malay states in the coastal areas of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra; Chi Tu, Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom, Gangga Negara, Langkasuka, Kedah, Pahang, the Melayu Kingdom and Srivijaya. Between the 7th and 13th centuries, many of these small, often prosperous peninsula and sumatran maritime trading states, became part of the mandala of Srivijaya,[50] a great confederation of city-states centred in Palembang,[51] Kadaram,[52] Chaiya and Tambralinga.

Srivijaya's influence spread over all the coastal areas of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, western Java and western Borneo, as well as the rest of the Malay Archipelago. Enjoying both Indian and Chinese patronage, its wealth was gained mostly through trade. At its height, the Old Malay language was used as its official language and became the lingua franca of the region, replacing Sanskrit, the language of Hinduism.[49] The Srivijayan era is considered the golden age of Malay culture.

The glory of Srivijaya however began to wane after the series of raids by the Indian Chola dynasty in the 11th century. By the end of the 13th century, the remnants of the Malay empire in Sumatra was finally destroyed by the Javanese invaders during the Pamalayu expedition (Pamalayu means "war against the Malays").

The complete destruction of Srivijaya caused the diaspora of the Srivijayan princes and nobles. Rebellions against the Javanese rule ensued and attempts were made by the fleeing Malay princes to revive the empire, which left the area of southern Sumatra in chaos and desolation. In 1299, through the support of the loyal servants of the empire, the Orang lauts, a Malay prince of Srivijaya origin, Sang Nila Utama established the Kingdom of Singapura in Temasek.[53] His dynasty ruled the island kingdom until the end of the 14th century, when the Malay polity once again faced the wrath of Javanese invaders. In 1400, his great great grandson, Parameswara, headed north and established the Malacca Sultanate.[54] The new kingdom succeeded Srivijaya and inherited much of the royal and cultural traditions, including a large part of the territories of its predecessor.[55][56][57]

The power vacuum left by the collapse of Srivijaya was filled by the growth of the kingdom of Tambralinga in the 12th century. Between the 13th to early 14th century, the kingdom succeeded to incorporate most of the Malay Peninsula under its mandala. The campaign led by Chandrabhanu Sridhamaraja (1230–1263) managed to capture Jaffna kingdom in Sri Lanka between 1247 and 1258. He was eventually defeated by the forces of the Pandyan dynasty from Tamil Nadu in 1263 and was killed by the brother of Emperor Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I.[58] The invasion marked an unrivaled feature in the history of Southeast Asia, it was the only time there was an armed maritime expedition beyond the borders of the region.

The cultivation of Malay polity system also diffused beyond the proper Sumatran-Peninsular border during this era. The age avowed by exploration and migration of the Malays to establish kingdoms beyond the traditional Srivijayan realm. Several exemplification are the enthronement of a Tambralingan prince to reign the Lavo Kingdom in present-day Central Thailand, the foundation of Rajahnate of Cebu in the Visayas and the establishment of the Tanjungpura Kingdom in what is now West Kalimantan, Borneo. The expansion is also eminent as it shaped the ethnogenesis development of the related Acehnese and Banjar people and further spreading the Indian-influenced Malay ethos within the regional sphere.

Islamisation

The period of the 12th and 15th centuries saw the arrival of Islam and the rise of the great port-city of Malacca on the southwestern coast of the Malay Peninsula[59] — two major developments that altered the course of Malay history.

The Islamic faith arrived on the shores of what are now the states of Kedah, Perak, Kelantan and Terengganu, from around the 12th century.[60] The earliest archaeological evidence of Islam from the Malay peninsula is the Terengganu Inscription Stone dating from the 14th century found in Terengganu state, Malaysia.[59]

By the 15th century, the Malacca Sultanate, whose hegemony reached over much of the western Malay Archipelago, had become the centre of Islamisation in the east. As a Malaccan state religion, Islam brought many great transformation into the Malaccan society and culture, and It became the primary instrument in the evolution of a common Malay identity.The Malaccan era witnessed the close association of Islam with Malay society and how it developed into a definitive marker of Malay identity.[12][61][62][63] Over time, this common Malay cultural idiom came to characterise much of the Malay Archipelago through the Malayisation process. The expansion of Malaccan influence through trade and Dawah brought with it together the Classical Malay language,[64] the Islamic faith,[65] and the Malay Muslim culture;[66] the three core values of Kemelayuan ("Malayness").[67]

In 1511, the Malaccan capital fell into the hands of Portuguese conquistadors. However, Malacca remained an institutional prototype: a paradigm of statecraft and a point of cultural reference for successor states such as Johor Sultanate (1528–present), Perak Sultanate (1528–present), Pahang Sultanate (1470–present), Siak Sri Indrapura Sultanate (1725–1946), Pelalawan Sultanate (1725–1946) and Riau-Lingga Sultanate (1824–1911).[68]

Across the South China Sea in the 14th century, another Malay realm, the Bruneian Empire was on the rise to become the most powerful polity in Borneo. By the middle of the 15th century, Brunei entered into a close relationship with the Malacca Sultanate. The sultan married a Malaccan princess, adopted Islam as the court religion, and introduced an efficient administration modelled on Malacca.[69] Brunei profited from trade with Malacca but gained even greater prosperity after the great Malay port was conquered by the Portuguese in 1511. It reached its golden age in the mid-16th century when it controlled land as far south as present day Kuching in Sarawak, north towards the Philippine Archipelago.[70] The empire broadened its influence in Luzon by defeating Datu Gambang of the Kingdom of Tondo and by founding a satellite state, Kota Seludong in present-day Manila, setting up the Muslim Rajah, Rajah Sulaiman I as a vassal to the Sultanate of Brunei. Brunei also expanded its influence in Mindanao, Philippines when Sultan Bolkiah married Leila Macanai, the daughter of the Sultan of Sulu. However, states like the Huangdom of Pangasinan, Rajahnate of Cebu and Kedatuan of Madja-as tried to resist Brunei's and Islam's spread into the Philippines. Brunei's fairly loose river based governmental presence in Borneo projected the process of Malayisation. Fine Malay Muslim cultures, including the language, dress and single-family dwelling were introduced to the natives primarily from ethnic Dayaks, drawing them into the Sultanate. Dayak chiefs were incorporated into the Malay hierarchy, being given the official titles of Datuk, Temenggong and Orang Kaya. In West Kalimantan, the development of such sultanates of Sambas, Sukadana and Landak tells a similar tale of recruitment among Dayak people.[71]

Other significant Malay sultanates were the Kedah Sultanate (1136–present), Kelantan Sultanate (1411–present) and Patani Sultanate (1516–1771) that dominated the northern part of the Malay peninsula. Jambi Sultanate (1460–1907), Palembang Sultanate (1550–1823) and Indragiri Sultanate (1298–1945) controlled much of the southeastern shores of Sumatra. While Deli Sultanate (1632–1946), Serdang Sultanate (1728–1948), Langkat Sultanate (1568–1948) and Asahan Sultanate (1630–1948) governed eastern Sumatra.

Colonisation

Between 1511 and 1984, numerous Malay kingdoms and sultanates fell under direct colonisation or became the protectorates of different foreign powers, from European colonial powers like Portuguese, Dutch and British, to regional powers like Siam and Japan. In 1511, the Portuguese Empire captured the capital city of the Malacca Sultanate. The victorious Portuguese however, were unable to extend their political influence beyond the fort of Malacca. The Sultan maintained his overlordship on the lands outside Malacca and established the Johor Sultanate in 1528 to succeed Malacca. Portuguese Malacca faced several unsuccessful retaliation attacks by Johor until 1614, when the combined forces of Johor and the Dutch Empire, ousted the Portuguese from the peninsula. As per agreement with Johor in 1606, the Dutch later took control of Malacca.[72]

Historically, Malay states of the peninsular had a hostile relation with the Siamese. Malacca sultanate herself fought two wars with the Siamese while northern Malay states came intermittently under Siamese dominance for centuries. In 1771, the Kingdom of Siam under the new Chakri Dynasty abolished the Pattani Sultanate and later annexed a large part of Kedah Sultanate. Earlier, the Siamese under Ayutthaya Kingdom have had already absorbed Tambralinga and overrun the Singgora Sultanate in the 17th century. In the early 19th century, the Siamese imposed a new administrative structure and created the semi-independent Malay kingdoms of Patani, Saiburi, Nongchik, Yaring, Yala, Reman and Rangae from Greater Pattani[73][74] and carved Satun, Perlis, Kubang Pasu from the Kedah Kingdom.[75][76]

In 1786, the island of Penang was leased to East India Company by Kedah Sultanate in exchange of military assistance against the Siamese. In 1819, the company also acquired Singapore from Johor Empire, later in 1824, Dutch Malacca from the Dutch, and followed by Dindings from Perak by 1874. All these trading posts officially known as Straits Settlements in 1826 and became the crown colony of British Empire in 1867. British intervention in the affairs of Malay states was formalised in 1895, when Malay rulers accepted British Residents in administration, and the Federated Malay States was formed. In 1909, Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Perlis were handed over by Siam to the British. These states along with Johor, later became known as Unfederated Malay States. During the World War II, all these British possessions and protectorates that collectively known as British Malaya were occupied by the Empire of Japan.

The twilight of the vast Bruneian Empire began during the Castille War against the Spanish conquistadors which arrived at the Philippines from Mexico. The war resulted in the end of the empire's dominance in the present-day Philippine archipelago. The decline further culminated in the 19th century, when the Sultanate lost most of its remaining territories in Borneo to the White Rajahs of Sarawak and North Borneo Chartered Company. Brunei was a British protectorate from 1888 to 1984.[2]

Following the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 which divided the Malay Archipelago into a British zone in the north and a Dutch zone in the south, all Malay sultanates in Sumatra and Southern Borneo became part of the Dutch East Indies. Though some of Malay sultans maintain their power under Dutch control,[77] some were abolished by the Dutch colonial government, like the case of Palembang Sultanate in 1823, Jambi Sultanate in 1906 and Riau Sultanate in 1911.

In the Pontianak incidents during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, the Japanese massacred most of the Kalimantan Malay elite and beheaded all of the Kalimantan Malay Sultans.

Malay nationalism

Despite the widespread distribution of the Malay population throughout the Malay archipelago, modern Malay nationalism was only significantly mobilised in the early twentieth century British Malaya i. e. the Malay Peninsula. In the Netherlands Indies, the struggle against colonisation was characterised by the trans-ethnic nationalism: the so-called "Indonesian National Awakening" united people from the various parts of the Dutch colony in the development of a national consciousness as "Indonesians".[80] In Brunei, despite some attempt made to arouse Malay political consciousness between 1942 and 1945, there was no significant history of ethnic-based nationalism. In Thailand however, Pattani separatism against Thai rule is regarded by some historians as a part of the wider sphere of peninsula Malay nationalism. A similar secession movement can be witnessed in modern-day Indonesia, where both autochthonously-Malay provinces of Riau and Riau Islands sought to gain independence under the name of Republic of Riau. Nevertheless, what follows is specific to the peninsula Malay nationalism that resulted in the formation of the Federation of Malaya, later reconstituted as Malaysia.

The earliest and most influential instruments of Malay national awakening were the periodicals which politicised the position of the Malays in the face of colonialism and alien immigration of non-Malays. In spite of repressions imposed by the British colonial government, there were no less than 147 journals and newspapers published in Malaya between 1876 and 1941. Among notable periodicals were Al-Imam (1906), Pengasuh (1920), Majlis (1935) and Utusan Melayu (1939). The rise of Malay nationalism was largely mobilised by three nationalist factions – the radicals distinguishable into the Malay left and the Islamic group which were both opposed to the conservative elites.[81]

The Malay leftists were represented by Kesatuan Melayu Muda, formed in 1938 by a group of Malay intelligentsia primarily educated in Sultan Idris Training College, with an ideal of Greater Indonesia. In 1945, they reorganised themselves into a political party known as Partai Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (PKMM). The Islamists were originally represented by Kaum Muda consisted of Middle east –educated scholars with Pan-Islamic sentiment. The first Islamic political party was Partai Orang Muslimin Malaya (Hizbul Muslimin) formed in March 1948, later succeeded by Pan-Malayan Islamic Party in 1951. The third group was the conservatives consisted of the westernised elites who were bureaucrats and members of royal families that shared a common English education mostly at the exclusive Malay College Kuala Kangsar. They formed voluntary organisations known as Persatuan Melayu ('Malay Associations') in various parts of the country with the primary goals of advancing and protecting the interests of Malays. In March 1946, 41 of these Malay associations formed United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), to assert Malay dominance over Malaya.[81]

The Malay and Malayness has been the fundamental basis for Malay ideology and Malay nationalism in Malaysia. All three Malay nationalist factions believed in the idea of a Bangsa Melayu ('Malay Nation') and the position of Malay language, but disagreed over the role of Islam and Malay rulers. The conservatives supported Malay language, Islam and Malay monarchy as constituting the key pillars of Malayness, but within a secular state that restricted the political role of Islam. The leftists concurred with the secular state but wanted to end feudalism, whereas the Islamic group favoured ending royalty but sought a much larger role of Islam.[82]

Since the foundation of Republic of Indonesia as a unitary state in 1950, all traditional Malay monarchies in Indonesia were abolished,[83] and the Sultans positions reduced to titular heads or pretenders. The violent demise of the Malay sultanates of Deli, Langkat, Serdang and Asahan in East Sumatra during the "Social revolution" of 1946, drastically influenced their Malayan counterparts and politically motivating them against the PKMM's ideal of Greater Indonesia and the Islamists' vision of Islamic Republic.

In March 1946, UMNO emerged with the full support of the Malay sultans from the Conference of Rulers. The new movement forged a close political link between rulers and subjects never before achieved. It generated an excited Malay public opinion which, together with the surprising political apathy of the non-Malays, led to Britain's abandonment of the radical Malayan Union plan. By July, UMNO succeeded in obtaining an agreement with the British to begin negotiations for a new constitution. Negotiations continued from August to November, between British officials on the one hand, and the Sultans' representatives and UMNO and the other.[84]

Two years later the semi independent Federation of Malaya was born. The new constitutional arrangement largely reverted to the basic pattern of pre-war colonial rule and built on the supremacy of the individual Malay states. Malay rights and privileges were safeguarded. The traditional Malay rulers thus retained their prerogatives, while their English-educated descendants came to occupy positions of authority at the centre, which was being progressively decolonised. In August 1957, the Federation of Malaya, the West's last major dependency in Southeast Asia, attained independence in a peaceful transfer of power.[84] The federation was reconstituted as Malaysia with the addition in 1963 of Singapore (separated in 1965), Sabah and Sarawak.

Culture

Language

The Malay language is one of the major languages of the world and of the Austronesian family. Variants and dialects of Malay are used as an official language in Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. The language is also spoken in Thailand, Cocos Island, Christmas Island, Sri Lanka. It is spoken natively by approximately 33 million people throughout the Malay Archipelago and is used as a second language by an estimated 220 million.[85]

The oldest form of Malay is descended from the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the earliest Austronesian settlers in Southeast Asia. This form would later evolved into Old Malay when Indian cultures and religions began penetrating the region. Old Malay contained some terms last until today, but remained unintelligible to modern speakers, while the modern language is already largely recognisable in written Classical Malay, which the oldest form dating back to 1303 CE.[86] Malay evolved extensively into Classical Malay through the gradual influx of numerous Arabic and Persian vocabulary, when Islam made its way to the region. Initially, Classical Malay was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Malay kingdoms of Southeast Asia. One of these dialects that was developed in the literary tradition of the Malacca Sultanate in the 15th century, eventually became predominant.

The Malaccan era marked with the transformation of the Malay language into an Islamic language, in similar fashion as the Arabic, Persian, Urdu and Swahili languages. An adapted Arabic script called Jawi was used replacing the Indian script, Islamic religious and cultural terminologies were abundantly assimilated, discarding many Hindu-Buddhist words, and Malay became the language of Islamic medium of instruction and dissemination throughout Southeast Asian region. At the height of Malacca's power in the 15th century, the Classical Malay spread beyond the traditional Malay speaking world[87] and resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bahasa Melayu pasar ("Bazaar Malay") or Bahasa Melayu rendah ("Low Malay") as opposed to the Bahasa Melayu tinggi ("High Malay") of Malacca.[88] It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin and the most important development, however, has been that pidgin creolised, creating several new languages such as the Ambonese Malay, Manado Malay and Betawi language.[89]

European writers of the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Tavernier, Thomassin and Werndly describe Malay as "language of the learned in all the Indies, like Latin in Europe".[90] It is also the most widely used during British and Dutch colonial era in the Malay Archipelago.[91] The dialect of Johor Sultanate, the direct successor of Malacca, became the standard speech among Malays in Singapore and Malaysia, and it formed the original basis for the standardised Indonesian language.[87][92][93][94]

Apart from the standard Malay, developed within the Malacca-Johor sphere, various local Malay dialects exist. For example, the Bangkanese, the Bruneian, the Jambian, the Kelantanese, the Kedahan, the Negeri Sembilanese, the Palembangnese, the Pattanese, the Sarawakian, the Terengganuan, and many others.

The Malay language was historically written in Pallawa, Kawi and Rencong. After the arrival of Islam, Arabic-based Jawi script was adopted and is still in use today as one of the two official scripts in Brunei and as an alternative script in Malaysia.[95] Beginning from the 17th century, as a result of British and Dutch colonisation, Jawi was gradually replaced by Rumi script[96] and eventually became the official modern script for Malay language in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, and co-official script in Brunei.

Literature

The rich oral literature and classical literature of the Malays contain a great number of portraits of the people, from the servant to the minister, from the judge to the Rajas, from the ancient to the very contemporary periods, which together form the amorphous identity of the Malays.[97]

Considering the softness and mellifluence of the Malay language, which lends itself easily to the requirements of rhyme and rhythm, the originality and beauty in Malay literature can be assessed in its poetical elements. Among the forms of poetry in Malay literature are – the Pantun, Syair and Gurindam. The earliest form of Malay literature was the oral literature and its central subjects are traditional folklore relating to nature, animals and people. The folklore were memorised and passed from one generation of storytellers to the next. Many of these tales were also written down by penglipur lara (storytellers) for example: Hikayat Malim Dewa, Hikayat Malim Deman, Hikayat Raja Donan, Hikayat Anggun Cik Tunggal, and Hikayat Awang Sulung Merah Muda.

When Indian influences made their way to the Malay Archipelago around 2000 years ago, Malay literature began incorporating Indian elements. Literature of this time is mostly translations of Sanskrit literature and romances, or at least some productions inspired by such, and is full of allusions to Hindu mythology. Probably to this early time may be traced such works as Hikayat Seri Rama (a free translation of the Ramayana), Hikayat Bayan Budiman (an adaptation of Śukasaptati) and Hikayat Panca Tanderan (an adaptation of Hitopadesha).[98]

The era of classical Malay literature started after the arrival of Islam and the invention of Jawi script (Arabic based Malay script). Since then, Islamic beliefs and concepts began to make its mark on Malay literature. The Terengganu Inscription Stone, which is dated to 1303, is the earliest known narrative Malay writing. The stone is inscribed with an account of history, law, and romance in Jawi script.[99] At its height, the Malacca Sultanate was not only the center of Islamisation, but also the center of Malay cultural expressions including literature. During this era, notable Middle Eastern literary works were translated and religious books were written in Malay language. Among famous translated works are Hikayat Muhammad Hanafiah and Hikayat Amir Hamzah. The rise of Malay literature during the period was also penned by other homegrown literary composition coloured by mystical Sufism of the middle-east, the notable works of Hamzah Fansuri such as Asrar al-Arifin (Rahsia Orang yang Bijaksana; The Secret of the Wise), Sharab al-Asyikin (Minuman Segala Orang yang Berahi; The Drink of All the Passionate) and Zinat al-Muwahidin (Perhiasan Sekalian Orang yang Mengesakan; The Ornament of All the Devoted) can be seen as the magna opera of the era.

The most important piece of Malay literary works is perhaps the famed Malay Annals or Sulalatus Salatin. It was called "the most famous, distinctive and best of all Malay literary works" by one of the most prominent scholars in Malay studies, Sir Richard O. Winstedt.[100] The exact date of its composition and the identity of its original author are uncertain, but under the order of Sultan Alauddin Riaayat Shah III of Johor in 1612, Tun Sri Lanang oversaw the editorial and compilation process of the Malay Annals.[101]

In the 19th century, the Malay literature received some notable additions through writings of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, a famous Malacca-born munshi of Singapore.[98] Abdullah is regarded as the most cultured Malay who ever wrote,[98] one of the greatest innovators in Malay letters[87] and the father of modern Malay literature.[99] His most important works are the Hikayat Abdullah (an autobiography), Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ke Kelantan (an account of his trip for the government to Kelantan), and Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ke Mekah (a narrative of his pilgrimage to Mecca 1854). His work was an inspiration to future generations of writers and marks an early stage in the transition from classical Malay literature to modern Malay literature.[87]

Religion

The early Malay communities were largely animists, believing in the existence of semangat (spirits) in everything.[49] Around the opening of the common era, Hinduism and Buddhism were introduced by Indian traders to the Malay Archipelago, where they flourished until the 13th century, just before the arrival of Islam brought by Arab, Indian and Chinese Muslim traders.

In the 15th century, Islam of the orthodox Sunni sect flourished in the Malay world under the Malacca Sultanate. In contrast with Hinduism, which transformed early Malay society only superficially, Islam can be said to have really taken root in the hearts and minds of the Malays.[102] Since this era, the Malays have traditionally had a close identification with Islam[103] and they have not changed their religion since.[102] This identity is so strong that it is said to become Muslim was to masuk Melayu (to enter Malayness).[61]

Nevertheless, the earlier beliefs having deeper roots, they have maintained themselves against the anathemas of Islam – and indeed Sufism or the mysticism of Shia Islam have become intertwined among the Malays, with the spirits of the earlier animistic world and some elements of Hinduism.[104] Following the 1970s, Islamic revival (also referred as re-Islamisation[105]) throughout the Muslim world, many traditions that contravene the teaching of Islam and contain elements of shirk were abandoned by the Malays. Among these traditions was the mandi safar festival (Safar bath), a bathing festival to achieve spiritual purity, in which can be discerned features similar to some of those of the Durga Puja of India.[106]

A majority of modern ethnic Malays are the adherents of Sunni Islam[107] and the most important Malay festivals are those of Islamic origin - Hari Raya Aidilfitri, Hari Raya Aidiladha, Awal Muharram, and Maulidur Rasul. It is considered "apostasy" for Malays to convert out of Islam in Malaysia. However, ethnic Malays living outside of Malaysia have also embraced other religions.

Architecture

Various cultural influences, notably Chinese, Indian and Europeans, played a major role in forming Malay architecture.[108] Until recent time, wood was the principal material used for all Malay traditional buildings.[109] However, numerous stone structures were also discovered particularly the religious complexes from the time of Srivijaya and ancient isthmian Malay kingdoms.

Candi Muara Takus and Candi Muaro Jambi in Sumatra are among the examples that associated with the architectural elements of Srivijaya Empire. However, the most of Srivijayan architecture was represented at Chaiya (now a province in Thailand) in Malay peninsular, which was without doubt a very important centre during the Srivijaya period.[110][111] The type of structure consists of a cell-chamber to house the Buddha image and the summit of structure was erected in the form of stupa with successive, superimposed terraces which is the best example at Wat Pra Borom That of Chaiya.[112]

There is also evidence of Hindu shrines or Candi around south Kedah between the mount Jerai and the Muda River valley, an area known as Bujang Valley. Within an area of about 350 square kilometres, 87 early historic religious sites have been reported and there are 12 candis located on mountain tops, a feature which suggests may derive from pre-historic Malay beliefs regarding sanctity of high places.[113]

Early reference on Malay architecture in Malay peninsula can be found in several Chinese records. A 7th-century Chinese account tells of Buddhist pilgrims calling at Langkasuka and mentioned the city as being surrounded by a wall on which towers had been built and was approached through double gates.[114] Another 7th-century account of a special Chinese envoy to Red Earth Kingdom in Malay peninsular, recorded that the capital city had three gates more than hundred paces apart, which were decorated with paintings of Buddhist themes and female spirits.[115]

The first detailed description of Malay architecture was on the great wooden Istana of Mansur Shah of Malacca (reigned 1458–1477).[109] According to Sejarah Melayu, the building had a raised seven bay structures on wooden pillars with a seven tiered roof in cooper shingles and decorated with gilded spires and Chinese glass mirrors.[116]

The traditional Malay houses are built using simple timber-frame structure. They have pitched roofs, porches in the front, high ceilings, many openings on the walls for ventilation,[117] and are often embellished with elaborate wood carvings. The beauty and quality of Malay wood carvings were meant to serve as visual indicators of the social rank and status of the owners themselves.[118]

Throughout many decades, the traditional Malay architecture has been influenced by Bugis and Java from the south, Siamese, British, Arab and Indian from the north, Portuguese, Dutch, Aceh and Minangkabau from the west and Southern Chinese from the east.[119]

Visual art

Wood carving is a part of classical Malay visual arts. The Malays had traditionally adorned their monuments, boats, weapons, tombs, musical instrument, and utensils by motives of flora, calligraphy, geometry and cosmic feature. The art is done by partially removing the wood using sharp tools and following specific patterns, composition and orders. The art form is seen as an act of devotion of the craftsmen to the creator and a gift to his fellowmen.[120]

The art form is mainly contributed due to the abundance of timber on the Malay Archipelago and also by the skilfulness of the woodcarvers that have allowed the Malays to practice woodcarving as a craft. The natural tropical settings where flora and fauna and cosmic forces is abundant has inspired the motives to be depict in abstract or styled form into the timber board. With the coming of Islam, geometric and Islamic calligraphy form were introduced in the wood carving. The woods used are typically from tropical hardwood species which is known to be durable and can resist the attacks of the fungi, power-boots beetles and termites.[121]

A typical Malay traditional houses or mosque would have been adorned with more than 20 carved components The carving on the walls and the panels allow the air breeze to circulate effectively in and out of the building and can let the sunlight to light the interior of the structure. At the same time, the shadow cast by the panels would also create a shadow based on the motives adding the beauty on the floor. Thus, the carved components performed in both functional and aesthetic purposes.

Cuisine

Different Malay regions are all known for their unique or signature dishes – Pattani, Kelantan and Terengganu for their Nasi dagang, Nasi kerabu and Keropok lekor; Jambi, Pahang, and Perak for their Durian-based cuisine especially gulai tempoyak; South Sumatra, Kedah, and Penang for their northern-style Asam laksa and rojak; Perlis and Satun for their Bunga kuda desserts; Negeri Sembilan for its lemak-based dishes, West Sumatra, Riau, Melaka, and Johor for their spicy Asam Pedas; Riau and Pahang for their ikan patin (Pangasius fish) dishes; Melayu Deli of Medan, North Sumatra for their Nasi goreng teri Medan (Medan anchovy fried rice) and Gulai Ketam (crab gulai),;[122] Jambi for its Panggang Ikan Mas; Palembang for its Mie celor and Pempek; Sarawak and Sambas for their Bubur pedas and laksa; Brunei for its unique Ambuyat dish.

The main characteristic in traditional Malay cuisine is undoubtedly the generous use of spices. The coconut milk is also important in giving the Malay dishes their rich, creamy character. The other foundation is belacan (shrimp paste), which is used as a base for sambal, a rich sauce or condiment made from belacan, chillies, onions and garlic. Malay cooking also makes plentiful use of lemongrass and galangal.[123]

Nearly every Malay meal is served with rice, the staple food in many other East Asian cultures. Although there are various type of dishes in a Malay meal, all are served at once, not in courses. Food is eaten delicately with the fingers of right hand, never with the left which is used for personal ablutions, and Malays rarely use utensils.[124] Because most of Malay people are Muslims, Malay cuisine follows Islamic halal dietary law rigorously. Protein intake are mostly taken from beef, water buffalo, goat, and lamb meat, and also includes poultry and fishes. Pork and any non-halal meats, also alcohol is prohibited and absent from Malay daily diet.

Nasi lemak, rice cooked in rich coconut milk probably is the most popular dish ubiquitous in Malay town and villages. Nasi lemak is considered as Malaysia's national dish.[125]

Another example is Ketupat or nasi himpit, glutinous compressed rice cooked in palm leafes, is popular especially during Idul Fitri or Hari Raya or Eid ul-Fitr. Various meats and vegetables could be made into Gulai or Kari, a type of curry dish with variations of spices mixtures that clearly display Indian influence already adopted by Malay people since ancient times. Laksa, a hybrid of Malay and Peranakan Chinese cuisine is also a popular dish. Malay cuisine also adopted some their neighbours' cuisine traditions, such as rendang adopted from Minangkabau in Sumatra, and satay from Java, however Malay people has developed their own distinctive taste and recipes.

Performing arts

The Malays have diverse kinds of music and dance which are fusions of different cultural influences. Typical genres range from traditional Malay folk dances dramas like Mak Yong to the Arab-influenced Zapin dances. Choreographed movements also vary from simple steps and tunes in Dikir barat to the complicated moves in Joget Gamelan.

Traditional Malay music is basically percussive. Various kinds of gongs provide the beat for many dances. There are also drums of various sizes, ranging from the large rebana ubi used to punctuate important events to the small jingled-rebana (frame drum) used as an accompaniment to vocal recitations in religious ceremonies.[126]

Nobat music became part of the Royal Regalia of Malay courts since the arrival of Islam in the 12th century and only performed in important court ceremonies. Its orchestra includes the sacred and highly revered instruments of nehara (kettledrums), gendang (double-headed drums), nafiri (trumpet), serunai (oboe), and sometimes a knobbed gong and a pair of cymbals.[127]

Indian influences are strong in a traditional shadow play known as Wayang Kulit where stories from Hindu epics; Ramayana & Mahabharata form the main repertoire. There are four distinctive types of shadow puppet theatre that can be found in Malay peninsula; Wayang Gedek, Wayang Purwa, Wayang Melayu and Wayang Siam.[128][129][130]

Other well-known Malay performing arts are; Bangsawan theatre, Dondang Sayang love ballad and Mak Inang dance from Malacca Sultanate, Jikey and Mek Mulung theatre from Kedah, Asyik dance and Menora dance drama from Patani and Kelantan, Ulek mayang and Rodat dance from Terengganu, Boria theatre from Penang, Canggung dance from Perlis, Mukun warble from Brunei and Sarawak,[131][132][133] Gending Sriwijaya from Palembang and Serampang Dua Belas dance from Serdang.[133]

Traditional dress

In Malay culture, clothes and textiles are revered items of beauty, power and status. Numerous accounts in Malay hikayats stressed the special place occupied by textiles.[134] The Malay handloom industry can be traced its origin since the 13th century when the eastern trade route flourished under Song dynasty. Mention of locally made textiles as well as the predominance of weaving in Malay peninsular was made in various Chinese and Arab accounts.[135] Among well-known Malay textiles are Songket and Batik.

Common classical Malay attire for men consists of a baju (shirt) or tekua (a type of a long sleeve shirt), baju rompi (vest), kancing (button), a small leg celana (trousers), a sarong worn around the waist, capal (sandal), and a tanjak or tengkolok (headgear); for the aristocrats, the baju sikap or baju layang (a type of coat) and pending (ornamental belt buckle) are also synonymous to be worn. It was also common for a pendekar (Malay warrior) to have a Kris tucked into the front fold of sarong.

Traditional Malay dress varies between different regions but the most popular traditional dress in modern-day are Baju Kurung (for women) and Baju Melayu (for men), which both recognised as the national dress for Malaysia and Brunei,[136][137] and also worn by Malay communities in Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand.

In contrast to Baju Melayu which continued to be worn as ceremonial dress only, Baju Kurung is worn daily throughout the year by a majority of Malay women. Sighting of female civil servants, professional workers and students wearing Baju Kurung is common in Malaysia and Brunei.

Martial arts

Silat and its variants can be found throughout the Malay world: the Malay peninsula (including Singapore), the Riau Islands, Sumatra and coastal areas of Borneo. Archaeological evidence reveals that, by the 6th century, formalised combat arts were being practised in the Malay peninsular and Sumatra.[138] The earliest forms of Silat are believed to have been developed and used in the armed forces of the ancient Malay kingdoms of Langkasuka (2nd century)[139][140] and Srivijaya (7th century).

The influence of the Malay sultanates of Malacca, Johor, Pattani and Brunei has contributed to the spread of this martial art in the Malay Archipelago. Through a complex maze of sea channels and river capillaries that facilitated exchange and trade throughout the region, Silat wound its way into the dense rainforest and up into the mountains. The legendary Laksamana Hang Tuah of Malacca is one of the most renowned pesilat (Silat practitioners) in history[141] and even considered by some as the father of Malay silat.[142] Since the classical era, Silat Melayu underwent great diversification and formed what is today traditionally recognised as the source of Indonesian Pencak Silat and other forms of Silat in Southeast Asia.[143][144]

Apart from Silat, Tomoi is also practised by Malays, mainly in the northern region of the Malay peninsula. It is a variant of Indo-Chinese forms of kickboxing which is believed to have been spread in the Southeast Asian mainland since the time of Funan Empire (68 AD).

Traditional games

Traditional Malay games usually require craft skills and manual dexterity and can be traced their origins since the days of Malacca Sultanate. Sepak Raga and kite flying are among traditional games that were mentioned in the Malay Annals being played by nobilities and royalties of the Malay sultanate.[145][146][147]

Sepak Raga is one of the most popular Malay games and has been played for centuries. Traditionally, Sepak raga was played in circle by kicking and keeps aloft the rattan ball using any part of the body except the arms and hands. It is now recognised as Malaysia's national sport[148][149] and played in the international sporting events such as Asian Games and Southeast Asian Games.

Other popular game is Gasing spinning which usually played after the harvest season. A great skill of craftsmanship is required to produce the most competitive Gasing (top), some of which spin for two hours at a time.[150]

Possibly the most popular Malay games is the Wau (a unique kind of kite from east coast of Malay peninsular) or kite flying. Wau-flying competitions take place with judges awarding points for craftsmanship (Wau are beautiful, colourful objects set on bamboo frames), sound (all Malay kites are designed to create a specific sound as they are buffeted about in the wind) and altitude.[150]

The Malays also have a variant of Mancala board game known as Congkak. The game is played by moving stones, marbles, beads or shells around a wooden board consisting of twelve or more holes. Mancala is acknowledged as the oldest game in the world and can be traced its origin since Ancient Egypt. As the game dispersed around the globe, every culture has invented its own variation including the Malays.[151]

Names and Titles

Malay personal names are complex, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the society, and titles are considered important. It has undergone tremendous change, evolving with the times to reflect the different influences that the Malays been subjected over the ages. Although some Malay names still retain parts of its indigenous Malay and Sanskrit influences, as Muslims, Malays have long favoured Arabic names as marks of their religion.

Malay names are patronymic and can be consisted of up to four parts; a title, a given name, the family name, and a description of the individual's male parentage. Some given names and father's names can be composed of double names and even triple names, therefore generating a longer name. For example, one of the Malaysian national footballer has the full name Mohd Aidil Zafuan Abdul Radzak, where 'Mohd Aidil Zafuan' is his triple given name and 'Abdul Radzak' is his father's double given name.

In addition to naming system, the Malay language also has a complex system of titles and honorifics, which are still extensively used in Malaysia and Brunei. By applying these Malay titles to a normal Malay name, a more complex name is produced. The current Prime Minister of Malaysia has the full name Dato' Seri Mohd Najib bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak, where 'Dato' Seri' is a Malay title of honour, 'Mohd Najib' is his personal name, 'bin' is derived from an Arabic word Ibnu meaning "son of" if in case of daughter it is replaced with binti, an Arabic word "bintun" meaning "daughter of", introduces his father's titles and names, 'Tun' is a higher honour, 'Haji' denotes his father's Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and 'Abdul Razak' is his father's personal name. The more extremely complex Malay names however, belong to the Malay royalties. The reigning Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia has the full regnal name Duli Yang Maha Mulia Almu'tasimu Billahi Muhibbuddin Tuanku AlHaj Abdul Halim Mu'adzam Shah Ibni AlMarhum Sultan Badlishah, while the reigning Sultan of Brunei officially known as Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu'izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar 'Ali Saifuddien Sa'adul Khairi Waddien.

Sub-ethnic groups

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malay people. |

- Anti-Malay racism, racial prejudice against ethnic Malays.

- Ketuanan Melayu (Malay Supremacy),

- List of Malays

- Malay folklore

- Ghost in Malay culture

- Malay Islamic Monarchy, the national philosophy of Negara Brunei Darussalam

- Malay units of measurement

References

- ↑ Economic Planning Unit (Malaysia) 2010

- 1 2 CIA World Factbook 2012

- ↑ Badan Pusat Statistika Indonesia 2010, p. 9

- ↑ World Population Review 2015

- ↑ CIA World Factbook 2012

- ↑ Malay, Cape in South Africa - Joshua Project

- ↑ Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka - Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012

- ↑ Australia - Ancestry

- ↑ Malay in United Kingdom - Joshua Project

- ↑ Malay in Myanmar - Joshua Project

- ↑ Milner 2010, pp. 24, 33

- 1 2 Barnard 2004, p. 7&60

- ↑ Melayu Online 2005.

- ↑ Milner 2010, pp. 200, 232.

- ↑ Milner 2010, p. 10 & 185.

- ↑ Milner 2010, p. 131

- ↑ Barnard 2004, pp. 7, 32, 33 & 43

- ↑ Abdul Rashid Melebek & Amat Juhari Moain 2006, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Barnard 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Milner 2010, pp. 22

- ↑ Barnard 2004, p. 3

- ↑ Deka 2007, p. 57

- ↑ Pande 2005, p. 266

- ↑ Gopal 2000, p. 139

- ↑ Ahir 1995, p. 612

- ↑ Mukerjee 1984, p. 212

- ↑ Sarkar 1970, p. 8

- ↑ Gerini 1974, p. 101

- ↑ I Ching 2005, p. xl-xli

- ↑ Melayu Online 2005

- ↑ Muljana 1981, p. 223

- ↑ Guoxue 2003

- ↑ Hall 1981, p. 190

- ↑ Cordier 2009, p. 105

- ↑ Wright 2004, pp. 364–365

- ↑ Ryan 1976, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Barnard 2004

- 1 2 Murdock 1969, p. 278

- ↑ Jamil Abu Bakar 2002, p. 39

- ↑ TED 1999

- ↑ COAC 2006

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). "The 'Austronesian' Story and Farming-language Dispersals: Caveats on the Timing and Independence in Proxy Lines of Evidence from the Indo-European Model". In Bacas, Elizabeth A.; Glover, Ian C.; Pigott, Vincent C. Uncovering Southeast Asia's Past. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 65–73. ISBN 9971-69-351-8.

- ↑ HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium; et al. (December 2009). "Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia". Science. 326 (5959): 1541–5. doi:10.1126/science.1177074. PMID 20007900.

- ↑ Soares, Pedro; et al. (June 2008). "Climate Change and Postglacial Human Dispersals in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. Oxford Journals. 25 (6): 1209–18. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn068. PMID 18359946.

- ↑ Geneticist clarifies role of Proto-Malays in human origin, Yahoo! News, 25 January 2012

- ↑ Terrell, John Edward (August–October 1999). "Think Globally, Act Locally". Current Anthropology. 40 (4): 559–560. doi:10.1086/200054.

- ↑ Baer v, A. S. (Fall 1999). "Eden in the East". Asian Perspectives. 38 (2): 256–258.

- ↑ Devan 2010

- 1 2 3 Zaki Ragman 2003, pp. 1–6

- ↑ Sabrizain 2006

- ↑ Munoz 2006, p. 171

- ↑ Muljana 2006

- ↑ Ministry of Culture 1973, p. 9

- ↑ Buyers 2008

- ↑ Alexander 2006, p. 8 & 126

- ↑ Stearns 2001, p. 138

- ↑ Wolters 1999, p. 33

- ↑ India's interaction with Southeast Asia,by Govind Chandra Pande p.286

- 1 2 Marshall Cavendish 2007, p. 1174

- ↑ Hussin Mutalib 2008, p. 25

- 1 2 Andaya & Andaya 1984, p. 55

- ↑ Mohd Fauzi Yaacob 2009, p. 16

- ↑ Abu Talib Ahmad & Tan 2003, p. 15

- ↑ Sneddon 2003, p. 74

- ↑ Milner 2010, p. 47

- ↑ Esposito 1999

- ↑ Mohamed Anwar Omar Din 2011, p. 34

- ↑ Harper 2001, p. 15

- ↑ Europa Publications Staff 2002, p. 203

- ↑ Richmond 2007, p. 32

- ↑ Milner 2010, pp. 82–84

- ↑ Hunter & Roberts 2010, p. 345

- ↑ Rashahar Ramli 1999, pp. 35–74

- ↑ Tongkat Ali 2010

- ↑ Andaya & Andaya 1984, pp. 62–68

- ↑ Ganguly 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Lumholtz 2004, p. 17

- ↑ Tan 1988, p. 14

- ↑ Chew 1999, p. 78

- ↑ Ricklefs, pp. 163–164.

- 1 2 Suryadinata 2000, pp. 133–136

- ↑ Barrington 2006, pp. 47–48

- ↑ He, Galligan & Inoguchi 2007, p. 146

- 1 2 Tirtosudarmo 2005

- ↑ Wright 2007, p. 492

- ↑ Teeuw 1959, p. 149

- 1 2 3 4 Sneddon 2003, p. 59

- ↑ Sneddon 2003, p. 84

- ↑ Sneddon 2003, p. 60

- ↑ Sweeney 1987

- ↑ Van der Putten & Cody 2009, p. 55

- ↑ Wong 1973, p. 126

- ↑ Clyne 1992, p. 413

- ↑ Brown & Ogilvie 2009, p. 678

- ↑ The Star 2008

- ↑ Omniglot 2012

- ↑ Littrup 1996, p. 192

- 1 2 3 Ford 1899, pp. 379–381

- 1 2 Marshall Cavendish 2007, p. 1218

- ↑ Boyd 1999, p. 756

- ↑ Johan Jaaffar, Safian Hussain & Mohd Thani Ahmad 1992, p. 260

- 1 2 Syed Husin Ali 2008, p. 57

- ↑ Johns & Lahoud 2005, p. 157

- ↑ Winstedt 1925, p. 125

- ↑ Burgat 2003, p. 54

- ↑ Bolton & Hutton 2000, p. 184

- ↑ Bethany World Prayer Center 1997

- ↑ Jan Henket & Heynen 2002, p. 181

- 1 2 Marshall Cavendish 2007, p. 1219

- ↑ Chihara 1996, p. 213

- ↑ Van Beek & Invernizzi 1999, p. 75

- ↑ Jermsawatdi 1989, p. 65

- ↑ O'Reilly 2007, p. 42

- ↑ Jamil Abu Bakar 2002, p. 59

- ↑ Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi 2005, p. 19

- ↑ Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi 2005, p. 24

- ↑ A. Ghafar Ahmad

- ↑ Farish Ahmad Noor & Khoo 2003, p. 47

- ↑ The Art of Living Show 2011

- ↑ Ismail Said 2005

- ↑ Ismail Said 2002

- ↑ Winarno 2011

- ↑ Alexander 2006, p. 58

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish 2007, p. 1222

- ↑ Malaysia.com 2011

- ↑ Moore 1998, p. 48

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish 2007, p. 1220

- ↑ Srinivasa 2003, p. 296

- ↑ Ghulam Sarwar Yousof 1997, p. 3

- ↑ Matusky 1993, pp. 8–11

- ↑ Marzuki bin Haji Mohd Seruddin 2009

- ↑ Mysarawak.org 2009

- 1 2 Ahmad Salehuddin 2009

- ↑ Maznah Mohammad 1996, p. 2

- ↑ Maznah Mohammad 1996, p. 19

- ↑ Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 2003

- ↑ Kementerian Kebudayaan, Belia dan Sukan 2009

- ↑ James 1994, p. 73

- ↑ Alexander 2006, p. 225

- ↑ Abd. Rahman Ismail 2008, p. 188

- ↑ Green 2001, p. 802

- ↑ Sheikh Shamsuddin 2005, p. 195

- ↑ Draeger 1992, p. 23

- ↑ Farrer 2009, p. 28

- ↑ Leyden 1821, p. 261

- ↑ Lockard 2009, p. 48

- ↑ Ooi 2004, p. 1357

- ↑ Ziegler 1972, p. 41

- ↑ McNair 2002, p. 104

- 1 2 Alexander 2006, p. 51

- ↑ Alexander 2006, p. 52

- ↑ In search of Brunei Malays outside Brunei

- ↑ Umaiyah Haji Omar 2003

- ↑ Umaiyah Haji Omar 2007

- ↑ IBP USA 2007, pp. 151–152

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Colling 1973, p. 6804

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mohd. Aris Hj. Othman 1983, pp. 1–26

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 M. G. Husain 2007, pp. 16, 33, 34

- 1 2 3 Gulrose Karim 1990, p. 74

- 1 2 3 Joseph & Najmabadi 2006, p. 436

- ↑ "Mempawah Sultanate<". Melaju Online.

- ↑ Majlis Kebudayaan Negeri Kedah 1986, pp. 19–69

Bibliography

- A. Ghafar Ahmad, Malay Vernacular Architecture, retrieved 24 June 2010

- Abd. Rahman Ismail (2008), Seni Silat Melayu: Sejarah, Perkembangan dan Budaya, Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 978-983-62-9934-5

- Abdul Rashid Melebek; Amat Juhari Moain (2006), Sejarah Bahasa Melayu ("History of the Malay Language"), Utusan Publications & Distributors, ISBN 967-61-1809-5

- Abu Talib Ahmad; Tan, Liok Ee (2003), New terrains in Southeast Asian history, Singapore: Ohio University press, ISBN 9971-69-269-4

- Ahir, Diwan Chand (1995), A Panorama of Indian Buddhism: Selections from the Maha Bodhi journal, 1892–1992, Sri Satguru Publications, ISBN 81-7030-462-8

- Ahmad Salehuddin (2009), Serampang dua belas, Tari Tradisional Kesultanan Serdang, retrieved 15 June 2012

- Alexander, James (2006), Malaysia Brunei & Singapore, New Holland Publishers, ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3

- Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M. Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2013). "Changing Ethnic Composition:Indonesia, 2000–2010" (PDF). XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference. Busan, Korea: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Yuzon (1984), A History of Malaysia, London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-27672-8

- Badan Pusat Statistika Indonesia (2010), Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010 - Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa sehari-hari penduduk Indonesia

- Barnard, Timothy P. (2004), Contesting Malayness: Malay identity across boundaries, Singapore: Singapore University press, ISBN 9971-69-279-1

- Barrington, Lowell (2006), After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-06898-2

- BBC News (11 December 2009), Genetic 'map' of Asia's diversity

- Bethany World Prayer Center (1997), The Malay of Malaysia, retrieved 28 February 2014

- Bethany World Prayer Center (1997), The Diaspora Malay, retrieved 28 February 2014

- Bolton, Kingsley; Hutton, Christopher (2000), Triad societies: western accounts of the history, sociology and linguistics of Chinese secret societies, 5, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24397-1

- Boyd, Kelly (1999), Encyclopedia of historians and historical writing, 2, London: Fitzroy Darborn Publishers, ISBN 1-884964-33-8

- Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2009), Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Elsevier Science, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7

- Burgat, François (2003), Face to face with political Islam (L'islamisme en face), New York: I.B Tauris & Co. Ltd, ISBN 1-86064-212-8

- Buyers, Christopher (2008), The Ruling House of Malacca – Johor

- Chew, Melanie (1999), The Presidential Notes: A biography of President Yusof bin Ishak, Singapore: SNP Publications, ISBN 978-981-4032-48-3

- Chihara, Daigorō (1996), Hindu-Buddhist architecture in Southeast Asia, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-10512-3

- CIA World Factbook (2012), Brunei, retrieved 28 February 2014

- CIA World Factbook (2012), Singapore, retrieved 28 February 2014

- Clyne, Michael G. (1992), Pluricentric languages: differing norms in different nations, De Gruyter Mouton, ISBN 978-3-11-012855-0

- COAC (2006), Orang Asli Population Statistics

- Colling, Patricia (1973), Dissertation Abstracts International, A-The Humanities and Social Sciences (Abstracts of Dissertations Available on Microfilm or as Xerographic Reproductions February 1973), 33, #8, New York: Xerox University Microfilms, ISSN 0419-4209

- Collins, Alan (2003), Security and Southeast Asia: domestic, regional, and global issues, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 981-230-230-1

- Cordier, Henri (2009), Ser Marco Polo; notes and addenda to Sir Henry Yule's edition, containing the results of recent research and discovery, Bibliolife, ISBN 978-1-110-77685-6

- Deka, Phani (2007), The great Indian corridor in the east, Mittal Publications, ISBN 81-8324-179-4

- Devan, Subhadra (2010), New interest in an older Lembah Bujang, NST

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc; Beardsmore, Hugo Baetens; Housen, Alex; Li, Wei (2003), Bilingualism: beyond basic principles, Multilingual Matters, ISBN 978-1-85359-625-4

- Draeger, Donn F. (1992), Weapons and fighting arts of Indonesia, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 0-8048-1716-2

- Economic Planning Unit (Malaysia) (2010), Population by sex, ethnic group and age, Malaysia,2010 (PDF)

- Esposito, John L. (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510799-9

- Europa Publications Staff (2002), Far East and Australasia (34th edition), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9

- Farish Ahmad Noor; Khoo, Eddin (2003), Spirit of wood: the art of Malay woodcarving : works by master carvers from Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pattani, Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., ISBN 0-7946-0103-0

- Farrer, D. S. (2009), Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-9355-5

- Ford, R. Clyde (1899), "Malay Literature", Popular Science Monthly, 55

- Ganguly, Šumit (1997), Government Policies and Ethnic Relations in Asia and the Pacific, MIT press, ISBN 978-0-262-52245-8

- Gerini, Gerolamo Emilio (1974), Researches on Ptolemy's geography of eastern Asia (further India and Indo-Malay archipelago, Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, ISBN 81-7069-036-6

- Ghulam Sarwar Yousof (1997), The Malay Shadow Play: An Introduction, The Asian Centre, ISBN 983-9499-02-5

- Gopal, Lallanji (2000), The economic life of northern India: c. A.D. 700–1200, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0302-2

- Guoxue (2003), Chronicle of Mongol Yuan

- Green, Thomas A. (2001), Martial arts of the world: An Encyclopedia., Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Inc, ISBN 1-57607-150-2

- Gulrose Karim, Information Malaysia 1990–91 Yearbook (1990), Muslim identity and Islam: misinterpreted in the contemporary world, Kuala Lumpur: Berita Publishing Sdn. Bhd, ISBN 81-7827-165-6

- Hall, Daniel George Edward (1981), History of South East Asia, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-24163-9

- Harper, Timothy Norman (2001), The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya, London: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00465-7

- Hatin, WI; Nur-Shafawati, AR; Zahri, M-K; Xu, S; Jin, L; et al. (2011), "Population Genetic Structure of Peninsular Malaysia Malay Sub-Ethnic Groups" in PLoS ONE 6(4): e18312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018312

- He, Baogang; Galligan, Brian; Inoguchi, Takashi (2007), Federalism in Asia, London: Edward Elgar Publications, ISBN 978-1-84720-140-9

- Hunter, William Wilson; Roberts, Paul Ernest (2010), A History of British India: To the Overthrow of the English in the Spice Archipelago, Nabu Press, ISBN 978-1-145-70716-0

- Hussin Mutalib (2008), Islam in Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-230-758-3

- I Ching (2005), Takakusu, Junjiro, ed., A Record of the Buddhist Religion As Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671–695), Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-1622-6

- IBP USA (2007), Brunei Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu'izzaddin Waddaulah Handbook (World Strategic and Business Information Library, International Business Publications, ISBN 978-1-4330-0444-5

- Ismail Said (2005), Criteria for Selecting Timber Species in Malay Woodcarving (PDF), University Teknologi Malaysia, retrieved 15 January 2011

- Ismail Said (2002), Visual Composition of Malay Woodcarvings in Vernacular House of Peninsular Malaysia (PDF), University Teknologi Malaysia, retrieved 15 January 2011

- James, Michael (1994), Black Belt, Rainbow Publications, ISSN 0277-3066

- Jamil Abu Bakar (2002), A design guide of public parks in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit UTM, ISBN 983-52-0274-5

- Jan Henket, Hubert; Heynen, Hilde (2002), Back from utopia: the challenge of the modern movement, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, ISBN 90-6450-483-0

- Jermsawatdi, Promsak (1989), Thai art with Indian influences, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-090-7

- Johan Jaaffar; Safian Hussain; Mohd Thani Ahmad (1992), History of Modern Malay Literature, Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka & Ministry of Education (Malaysia), ISBN 983-62-2745-8

- Johns, Anthony Hearle; Lahoud, Nelly (2005), Islam in world politics, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32411-4

- Joseph, Suad; Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2006), Economics, Education, Mobility And Space (Encyclopedia of women & Islamic cultures), Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-12820-0

- Kementerian Kebudayaan; Belia dan Sukan (2009), Pakaian Tradisi, Pelita Brunei, retrieved 20 July 2010

- Leyden, John (1821), Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown

- Littrup, Lisbeth (1996), Identity in Asian literature, Richmond: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, ISBN 0-7007-0367-5

- Lockard, Craig A. (2009), Southeast Asia in world history, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533811-9

- Lumholtz, Carl Sofus (2004), Through Central Borneo, Kessinger publishing, ISBN 978-1-4191-8996-8

- M. G. Husain (2007), Muslim identity and Islam: misinterpreted in the contemporary world, New Delhi: Manak Publications, ISBN 81-7827-165-6

- Majlis Kebudayaan Negeri Kedah (1986), Intisari kebudayaan Melayu Kedah: Kumpulan rencana mengenai kebudayaan Negeri Kedah, Majlis Kebudayaan Negeri Kedah

- Malaysia.com (2011), Nasi Lemak, retrieved 6 July 2010

- Marshall Cavendish (2007), World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, New York: Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3

- Marzuki bin Haji Mohd Seruddin (2009), Program Kerjasama Brunei-Malaysia tingkatkan seni Budaya, Pelita Brunei, retrieved 15 June 2012

- Matusky, Patricia Ann (1993), Malaysian shadow play and music: continuity of an oral tradition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 967-65-3048-4

- Maznah Mohammad (1996), The Malay handloom weavers: a study of the rise and decline of traditional manufacture, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 981-3016-99-X

- McNair, Sylvia (2002), Malaysia (Enchantment of the World. Second Series), Children's Press, ISBN 0-516-21009-2

- Melayu Online (2005), Melayu Online.com's Theoretical Framework

- Milner, Anthony (2010), The Malays (The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4443-3903-1

- Ministry of Culture, Singapore (1973), Singapore: facts and pictures, ISSN 0217-7773

- Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi (2005), The architectural heritage of the Malay world: the traditional houses, Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit UTM, ISBN 983-52-0357-1

- Mohamed Anwar Omar Din (2011), Asal Usul Orang Melayu: Menulis Semula Sejarahnya (The Malay Origin: Rewrite Its History), Jurnal Melayu, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, retrieved 4 June 2012

- Mohd. Aris Hj. Othman (1983), The dynamics of Malay identity, Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, ISBN 978-967-942-009-8

- Mohd Fauzi Yaacob (2009), Malaysia: Transformasi dan perubahan sosial, Kuala Lumpur: Arah Pendidikan Sdn Bhd, ISBN 978-967-323-132-4

- Moore, Wendy (1998), West Malaysia and Singapore, Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd, ISBN 962-593-179-1

- Mysarawak.org (2009), Seni Bermukun Semakin Malap, retrieved 15 June 2012

- Mukerjee, Radhakamal (1984), The culture and art of India, Coronet Books Inc, ISBN 978-81-215-0114-9

- Muljana, Slamet (1981), Kuntala, Sriwijaya Dan Suwarnabhumi, Yayasan Idayu, ASIN B0000D7HOP

- Muljana, Slamet (2006), Stapel, Frederik Willem, ed., Sriwijaya, PT. LKiS Pelangi Aksara, ISBN 978-979-8451-62-1

- Munoz, Paul Michel (2006), Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, ISBN 981-4155-67-5

- Murdock, George Peter (1969), Studies in the science of society, Singapore: Books for Libraries Press, ISBN 978-0-8369-1157-2

- O'Reilly, Dougald J. W. (2007), Early civilizations of Southeast Asia, Rowman Altamira Press, ISBN 978-0-7591-0278-1

- Omniglot (2012), Malay (Bahasa Melayu)

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004), Southeast Asia: a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-770-5

- Pande, Govind Chandra (2005), India's Interaction with Southeast Asia: History of Science,Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 1, Part 3, Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 978-81-87586-24-1

- Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia (2003), Royal and Palace Cutoms:Dresses For Ceremonies And Functions, retrieved 20 July 2010

- Pogadaev, V.A. (2012), Malay World (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore). Lingua-Cultural Dictionary), Vostochnaya Kniga, ISBN 978-5-7873-0658-3

- Rashahar Ramli (1999), Masyarakat Melayu dan penanaman padi di Selatan Thailand : kajian kes di sebuah mubaan dalam Wilayah / Narathiwat (PDF), UM Digital Repository

- Richmond, Simon (2007), Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei, Lonely Planet publications, ISBN 978-1-74059-708-1

- Ryan, Neil Joseph (1976), A History of Malaysia and Singapore, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-580302-7

- Sabrizain (2006), Early Malay kingdoms

- Sarkar, Himansu Bhusan (1970), Some contributions of India to the ancient civilisation of Indonesia and Malaysia, Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, ISBN 0-19-580302-7

- Sheikh Shamsuddin (2005), The Malay art of self-defense: Silat Seni Gayung, Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, ISBN 1-55643-562-2

- Sneddon, James N. (2003), The Indonesian language: its history and role in modern society, University of New South Wales Press, ISBN 0-86840-598-1

- Srinivasa, Kodaganallur Ramaswami (2003), Asian variations in Ramayana, Singapore: Sahitya Academy, ISBN 81-260-1809-7

- Stearns, Peter N. (2001), The Encyclopedia of World History ( volume 1), Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4

- Suryadinata, Leo (2000), Nationalism & Globalization: East & West, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-230-078-2

- Sweeney, Amin (1987), A full hearing:orality and literacy in the Malay world, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05910-7

- Syed Husin Ali (2008), The Malays, their problems and future, Kuala Lumpur: The Other Press Sdn Bhd, ISBN 978-983-9541-62-5

- Tan, Liok Ee (1988), The Rhetoric of Bangsa and Minzu, Monash Asia Institute, ISBN 978-0-86746-909-7

- TED (1999), Taman Negara Rain Forest Park and Tourism