Development of the Christian biblical canon

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Interpretation |

|

Perspectives |

|

|

The Christian biblical canons are the books Christians regard as divinely inspired and constituting a Christian Bible. Books included in the Christian biblical canons of both the Old and New Testament were decided by the 5th century for the ancient undivided Church (which includes both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions) and was reaffirmed by the Catholic Church in the wake of the Protestant Reformation at the Council of Trent (1546). The canons of the Church of England and English Calvinists were decided definitively by the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) and the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647), respectively. The Synod of Jerusalem (1672) established additional canons that are widely accepted throughout the Orthodox Church. The Old and New Testament canons did not develop independently of each other and most primary sources for the canon specify both Old and New Testament books. A comprehensive table of biblical scripture for both Testaments, with regard to canonical acceptance in Christendom's various major traditions, can be found here.

Development of the Old Testament canon

The Old Testament (sometimes abbreviated OT) is the first section of the two-part Christian Biblical canon and is based on the Hebrew Bible but can include several Deuterocanonical books or Anagignoskomena depending on the particular Christian denomination. For a full discussion of these differences, see Books of the Bible.

Following Jerome's Veritas Hebraica, the Protestant Old Testament consists of the same books as the Hebrew Bible, but the order and numbering of the books are different. Protestants number the Old Testament books at 39, while the Jews number the same books as 24. This is because the Jews consider Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles to form one book each, group the 12 minor prophets into one book, and also consider Ezra and Nehemiah a single book.

The traditional explanation of the development of the Old Testament canon describes two sets of Old Testament books, the protocanonical books and the deuterocanonical books (the latter considered non-canonical by Protestants). According to this theory, certain Church fathers accepted the inclusion of the deuterocanonical books based on their inclusion in the Septuagint (most notably Augustine), while others disputed their status and did not accept them as divinely inspired scripture (most notably Jerome). Michael Barber, a Roman Catholic theologian, argues that this reconstruction is grossly inaccurate.[1]

| ~ Books of the Old Testament ~ |

|---|

| The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh.

Common to Judaism, Samaritanism and Christianity (excepting the minority of Protestant denominations sometimes called New Testament only Christians which reject the "Old Testament") |

| Common to Judaism and Christianity but excluded by Samaritans

|

Included by Roman Catholics, Orthodox, but excluded by Jews, Samaritans and most Protestants:

|

Included by Orthodox (Synod of Jerusalem):

|

| Included by Russian and Ethiopian Orthodox: |

| Included by Ethiopian Orthodox: |

| Included by Syriac Peshitta Bible: |

Development of the New Testament canon

The development of the New Testament canon was, like that of the Old Testament, a gradual process.

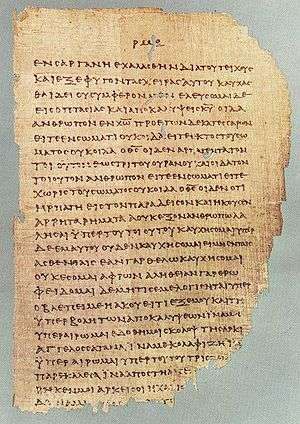

Irenaeus (died c. 202) quotes and cites 21 books that would end up as part of the New Testament, but does not use Philemon, Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 3 John and Jude.[3] By the early 3rd century Origen of Alexandria may have been using the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Revelation,[4] see also Antilegomena. Likewise by 200 the Muratorian fragment shows that there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to what is now the New Testament, which included four gospels and argued against objections to them.[5] Thus, while there was plenty of discussion in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the "major" writings were accepted by almost all Christian authorities by the middle of the second century.[6]

The next two hundred years followed a similar process of continual discussion throughout the entire Church, and localized refinements of acceptance. As the Church worked to become of one mind, the approximate completeness of agreement merged gradually closer to unity. This process was not yet complete at the time of the First Council of Nicaea in 325, though substantial progress had been made by then. Though a list was clearly necessary to fulfill Constantine's commission in 331 of fifty copies of the Bible for the Church at Constantinople, no concrete evidence exists to indicate that it was considered to be a formal canon. In the absence of a canonical list, the resolution of questions would normally have been directed through the see of Constantinople, in consultation with Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (who was given the commission), and perhaps other bishops who were available locally.

In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books that would formally become the New Testament canon,[7] and he used the word "canonized" (kanonizomena) in regard to them.[8] The first council that accepted the present Catholic canon (the Canon of Trent) may have been the Synod of Hippo Regius in North Africa (393); the acts of this council, however, are lost. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Councils of Carthage in 397 and 419.[9] These councils took place under the authority of St. Augustine, who regarded the canon as already closed.[10] Pope Damasus I's Council of Rome in 382, if the Decretum Gelasianum is correctly associated with it, issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above,[7] or if not the list is at least a 6th-century compilation[11] claiming a 4th-century imprimatur.[12] Likewise, Damasus's commissioning of the Latin Vulgate edition of the Bible, c. 383, was instrumental in the fixation of the canon in the West.[13] In 405, Pope Innocent I sent a list of the sacred books to a Gallic bishop, Exsuperius of Toulouse. When these bishops and councils spoke on the matter, however, they were not defining something new, but instead "were ratifying what had already become the mind of the church."[14] Thus, from the 5th century onward, the Western Church was unanimous concerning the New Testament canon.[15]

The last book to be accepted universally was the Book of Revelation, though with time all the Eastern Church also agreed. Thus, by the 5th century, both the Western and Eastern churches had come into agreement on the matter of the New Testament canon.[16] The Council of Trent of 1546 reaffirmed that finalization for Roman Catholicism in the wake of the Protestant Reformation.[17] The Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563 for the Church of England and the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1647 for English Calvinism established the official finalizations for those new branches of Christianity in light of the break with Rome. The Synod of Jerusalem of 1672 made no changes to the New Testament canon for any Orthodox, but resolved some questions about some of the minor Old Testament books for the Greek Orthodox and most other Orthodox jurisdictions (who chose to accept it).

| ~ Books of the New Testament ~ |

|---|

References

- ↑ Barber, Michael (2006-03-04). "Loose Canons: The Development of the Old Testament (Part 1)". Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ These are one book in the Jewish Bible, called "Trei Asar" or "Twelve".

- ↑ Bruce, F. F. The Books and the Parchments. (Fleming H. Revell Company, 1963) p. 109.

- ↑ Both points taken from Mark A. Noll's Turning Points, (Baker Academic, 1997) pp. 36–37.

- ↑ H. J. De Jonge, "The New Testament Canon," in The Biblical Canons. eds. de Jonge & J. M. Auwers (Leuven University Press, 2003) p. 315.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of the Bible (volume 1) eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans (Cambridge University Press, 1970) p. 308.

- 1 2 Lindberg, Carter (2006). A Brief History of Christianity. Blackwell Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 1-4051-1078-3.

- ↑ Brakke, David (October 1994). "Canon Formation and Social Conflict in Fourth-Century Egypt: Athanasius of Alexandria's Thirty-Ninth 'Festal Letter'". The Harvard Theological Review. 87 (4): 395–419. JSTOR 1509966.

- ↑ McDonald & Sanders' The Canon Debate, Appendix D-2, note 19: "Revelation was added later in 419 at the subsequent synod of Carthage."

- ↑ Everett Ferguson, "Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon," in The Canon Debate. eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002) p. 320; F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 230; cf. Augustine, De Civitate Dei 22.8

- ↑ F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 234

- ↑ Burkitt, F. C. (1913). "The Decretum Gelasianum". Journal of Theological Studies. 14: 469–471. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ↑ F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 225

- ↑ Everett Ferguson, "Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon," in The Canon Debate. eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002) p. 320, which cites: Bruce Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origins, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon, 1987) pp. 237–238, and F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 97

- ↑ F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 215

- ↑ The Cambridge History of the Bible (volume 1) eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans (Cambridge University Press, 1970) p. 305; cf. the Catholic Encyclopedia, Canon of the New Testament

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, Canon of the New Testament

Further reading

- Armstrong, Karen (2007) The Bible: A Biography. Books that Changes the World Series. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-969-3

External links

- WELS Topical Q&A: Canon - 66 Books in the Bible, by Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (Confessional Lutheran perspective)