Gravitropism

Gravitropism (also known as geotropism) is a turning or growth movement by a plant or fungus in response to gravity. It is a general feature of all higher and many lower plants as well as other organisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first to scientifically document that roots show positive gravitropism and stems show negative gravitropism. That is, roots grow in the direction of gravitational pull (i.e., downward) and stems grow in the opposite direction (i.e., upwards). This behavior can be easily demonstrated with any potted plant. When laid onto its side, the growing parts of the stem begin to display negative gravitropism, growing (biologists say, turning; see tropism) upwards. Herbaceous (non-woody) stems are capable of a small degree of actual bending, but most of the redirected movement occurs as a consequence of root or stem growth outside.

Gravitropism in the root

Root growth occurs by division of stem cells in the root meristem located in the tip of the root, and the subsequent expansion of cells in a region just primal to the tip known as the elongation zone. Differential growth during tropisms mainly involves changes in cell expansion versus changes in cell division, although a role for cell division in tropic growth has not been formally ruled out. Gravity is sensed in the root tip and this information must then be relayed to the elongation zone so as to maintain growth direction and mount effective growth responses to changes in orientation and continue to grow its roots in the same direction as gravity (Perrin et al., 2005).

Abundant evidence demonstrates that roots bend in response to gravity due to a regulated movement of the plant hormone auxin known as polar auxin transport (Swarup et al., 2005). This was described in the 1920s in the Cholodny-Went model. The model was independently proposed by the Russian scientist N. Cholodny of the University of Kiev in 1927 and by Frits Warmolt Went of the California Institute of Technology in 1928, both based on work they had done in 1926.[1] Auxin exists in nearly every organ and tissue of a plant, but its has been reoriented in the gravity field, can initiate differential growth resulting in root curvature.

Gravitropism in shoots

Gravitropism is an integral part of plant growth, orienting its position to maximize contact with sunlight, as well as ensuring that the roots are growing in the correct direction. Growth due to gravitropism is mediated by changes in concentration of the plant hormone auxin within plant cells.

Differential sensitivity to auxin helps explain Darwin's original observation that stems and roots respond in the opposite way to the forces of gravity. In both roots and stems, auxin accumulates towards the gravity vector on the lower side. In roots, this results in the inhibition of cell expansion on the lower side and the concomitant curvature of the roots towards gravity (positive gravitropism). In stems, the auxin also accumulates on the lower side, however in this tissue it increases cell expansion and results in the shoot curving up (statolithic gravitropism).

Upward growth of plant parts, against gravity, is called "negative gravitropism", and downward growth of roots is called "positive gravitropism".

Statoliths: how plants sense gravity

In the root cap (a tissue at the tip of the root) there is a special subset of cells, called statocytes. Inside the statocyte cells, some specialized amyloplasts are involved in the perception of gravity by the plant (gravitropism). These specialized amyloplasts—called statoliths—are denser than the cytoplasm and can sediment according to the gravity vector. The statoliths are enmeshed in a web of actin and it is thought that their sedimentation transmits the gravitropic signal by activating mechanosensitive channels. The gravitropic signal then leads to the reorientation of auxin efflux carriers and subsequent redistribution of auxin streams in the root cap and root as a whole. The changed relations in concentration of auxin leads to differential growth of the root tissues. Taken together, the root is then turning to follow the gravity stimuli. Statoliths are also found in the endodermic layer of the inflorescence stem. The redistribution of auxin causes the shoot to turn in a direction opposite that of the gravity stimuli.

Modulation by phytochrome

Apart being itself the tropic factor (phototropism), light may also suppress the gravitropic reaction. As changes introduced by red light can often be reversed by the far red light, this regulation is believed to be phytochrome-mediated.[2]

Compensation

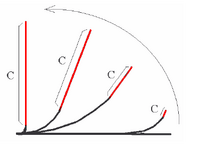

Bending mushroom stems follow some regularities that are not common in plants. After turning into horizontal the normal vertical orientation the apical part (region C in the figure below) starts to straighten. Finally this part gets straight again, and the curvature concentrates near the base of the mushroom. This effect is called compensation (or sometimes, autotropism). The exact reason of such behavior is unclear, and at least two hypotheses exist.

- The hypothesis of plagiogravitropic reaction supposes some mechanism that sets the optimal orientation angle other than 90 degrees (vertical). The actual optimal angle is a multi-parameter function, depending on time, the current reorientation angle and from the distance to the base of the fungi. The mathematical model, written following this suggestion, can simulate bending from the horizontal into vertical position but fails to imitate realistic behavior when bending from the arbitrary reorientation angle (with unchanged model parameters).

- The alternative model supposes some “straightening signal”, proportional to the local curvature. When the tip angle approaches 30° this signal overcomes the bending signal, caused by reorientation, resulting straightening.

Both models fit the initial data well, but the latter was also able to predict bending from various reorientation angles. Compensation is less obvious in plants, but in some cases it can be observed combining exact measurements with mathematical models. The more sensitive roots are stimulated by lower levels of auxin; higher levels of auxin in lower halves stimulate less growth, resulting in downward curvature (positive gravitropism).

Gravitropic mutants

Mutants with altered responses to gravity have been isolated in several plant species including Arabidopsis thaliana (one of the genetic model systems used for plant research). These mutants have alterations in either negative gravitropism in hypocotyls and/or shoots, or positive gravitropism in roots, or both. Mutants have been identified with varying effects on the gravitropic responses in each organ, including mutants which nearly eliminate gravitropic growth, and those whose effects are weak or conditional. Once a mutant has been identified, it can be studied to determine the nature of the defect (the particular difference(s) it has compared to the non-mutant 'wildtype'). This can provide information about the function of the altered gene, and often about the process under study. In addition the mutated gene can be identified, and thus something about its function inferred from the mutant phenotype.

Gravitropic mutants have been identified that effect starch accumulation, such as those affecting the PGM1 gene in Arabidopsis, causing plastids - the presumptive statoliths - to be less dense and, in support of the starch-statolith hypothesis, less sensitive to gravity. Other examples of gravitropic mutants include those affecting the transport or response to the hormone auxin. In addition to the information about gravitropsim which such auxin-transport or auxin-response mutants provide, they have been instrumental in identifying the mechanisms governing the transport and cellular action of auxin as well as its effects on growth.

There are also several cultivated plants that display altered gravitropism compared to other species or to other varieties within their own species. Some are trees that have a weeping or pendulate growth habit; the branches still respond to gravity, but with a positive response, rather than the normal negative response. Others are the lazy (i.e. ageotropic or agravitropic) varieties of corn (Zea mays) and varieties of rice, barley and tomatoes, whose shoots grow along the ground.

See also

- Clinostat - a device used to negate the effects of gravitational pull.

- Amyloplast - starch organelle involved in sensing gravitropism

References

- ↑ Janick, Jules (2010). Horticultural Reviews. John Wiley & Sons. p. 235. ISBN 0470650532.

- ↑ E. Liscum and R. P. Hangarter, 1993 Genetic Evidence That the Red-Absorbing Form of Phytochrome B Modulates Gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology, 103 no. 1 15-19

- Hou G, Kramer VL, Wang YS, Chen R, Perbal G, Gilroy S, Blancaflor EB (2004). The promotion of gravitropism in Arabidopsis roots upon actin disruption is coupled with the extended alkalinization of the columella cytoplasm and a persistent lateral auxin gradient.Plant J. 39(1):113-25.

- Meškauskas A., Moore D., Novak Frazier L. (1999). Mathematical modelling of morphogenesis in fungi. 2. A key role for curvature compensation ('autotropism') in the local curvature distribution model. New Phytologist, 143, 387-399.

- Meškauskas A., Jurkoniene S., Moore D. (1999). Spatial organization of the gravitropic response in plants: applicability of the revised local curvature distribution model to Triticum aestivum coleoptiles. New Phytologist 143, 401-407.

- Perrin RM, Young LS, Murthy U M N, Harrison BR, Wang Y, Will JL, Masson PH (2005). Gravity signal transduction in primary roots. Ann Bot. 2005 Oct;96(5):737-43.

- Swarup R, Kramer EM, Perry P, Knox K, Leyser HM, Haseloff J, Beemster GT, Bhalerao R, Bennett MJ (2005). Root gravitropism requires lateral root cap and epidermal cells for transport and response to a mobile auxin signal. Nat Cell Biol. Nov;7(11):1057-65.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gravitropism. |