French phonology

|

| Part of a series on the |

| French language |

|---|

| History |

|

|

| Grammar |

| Orthography |

| Phonology |

|

French phonology is the sound system of French. This article discusses mainly the phonology of Standard French of the Parisian dialect. Notable phonological features include its uvular r, nasal vowels, and three processes affecting word-final sounds: liaison, a specific instance of sandhi in which word-final consonants are not pronounced unless they are followed by a word beginning with a vowel; elision in which certain instances of /ə/ (schwa) are elided (such as when final before an initial vowel) and enchaînement (resyllabification) in which word-final and word-initial consonants may be moved across a syllable boundary, with syllables crossing word boundaries:

An example of the various processes is this:

- Written: On a laissé la fenêtre ouverte.

- Meaning: "The window has been left open."

- In isolation: /ɔ̃ a lɛse la fənɛːtʁ uvɛʁt/

- Together: [ɔ̃.na.lɛ.se.laf.nɛː.tχu.vɛχt]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | (x) | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | |||

| Approximant | plain | l | j | ||||

| rounded | ɥ | w | |||||

Phonetic notes:

- /n, t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪],[2][3] while /s, z/ are dentalized laminal alveolar [s̪, z̪] (commonly called 'dental'), pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the back of the upper front teeth, with the tip resting behind lower front teeth.[2][4]

- /l/ is usually apical alveolar [l̺] but sometimes laminal denti-alveolar [l̪].[3] Before /f, ʒ/, it can be realised as retroflex [ɭ].[3]

- In current pronunciation, /ɲ/ is merging with /nj/.[5]

- The velar nasal /ŋ/ is not a native phoneme of French, but it occurs in loan words such as camping, bingo or kung-fu.[6] Some speakers who have difficulty with this consonant realise it as a sequence [ŋɡ] or replace it with /ɲ/.[7]

- The approximants /j, ɥ, w/ correspond to the close vowels /i, y, u/. While there are a few minimal pairs (such as loua /lu.a/ 's/he rented' and loi /lwa/ 'law'), there are many cases where there is free variation.[8]

- Some dialects of French have a palatal lateral /ʎ/ (French: l mouillé, 'moistened l'), but in the modern standard variety, it has merged with /j/.[9] See also Glides and diphthongs, below.

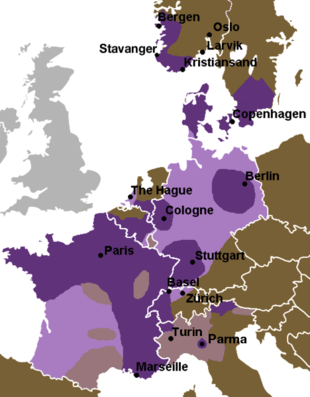

- The French rhotic has a wide range of realizations: the voiceless or voiced uvular fricatives [χ] and [ʁ] (the latter also realized as an approximant), the uvular trill [ʀ], the alveolar trill [r], and the alveolar tap [ɾ]. These are all recognized as the phoneme /ɲ/,[8] but all except [ʁ] and [χ] are considered dialectal. [ʁ] is the standard consonant. Although the voiceless [χ] is pronounced before or after a voiceless obstruant or at the end of a sentence, the voiced symbol [ʁ] is often used in phonemic transcriptions. See French guttural r and map at right.

- The phoneme /x/ is not a native phoneme of French but occurs in loan words such as khamsin, manhua or jota. People who have difficulty with this sound usually replace it with either /ʁ/, or use a spelling pronunciation (i.e. /kam.sin/, /man.wa/…).

- Some speakers pronounce /k/ and /ɡ/ as [c] and [ɟ] before /i, e, ɛ, a, ɛ̃/ and at the end of a word.[10]

| Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Example | Gloss | IPA | Example | Gloss | ||

| /p/ | /pu/ | pou | 'louse' | /b/ | /bu/ | boue | 'mud' |

| /t/ | /tu/ | tout | 'all' | /d/ | /du/ | doux | 'sweet' |

| /k/ | /ku/ | cou | 'neck' | /ɡ/ | /ɡu/ | goût | 'taste' |

| /f/ | /fu/ | fou | 'crazy' | /v/ | /vu/ | vous | 'you' |

| /s/ | /su/ | sous | 'under' | /z/ | /zo/ | zoo | 'zoo' |

| /ʃ/ | /ʃu/ | chou | 'cabbage' | /ʒ/ | /ʒu/ | joue | 'cheek' |

| /m/ | /mu/ | mou | 'soft' | ||||

| /n/ | /nu/ | nous | 'we, us' | ||||

| /ɲ/ | /ɲuf/ | gnouf | 'prison' (slang) | ||||

| /ŋ/ | /paʁkiŋ/ | parking | 'parking lot' | ||||

| /l/ | /lu/ | loup | 'wolf' | ||||

| /ʁ/ | /ʁu/ | roue | 'wheel' | ||||

Geminates

Although double consonant letters appear in the orthographic form of many French words, geminate consonants are relatively rare in the pronunciation of such words. The following cases can be identified.[12]

The pronunciation [ʁː] is found in the future and conditional forms of the verbs courir ('to run') and mourir ('to die'). The conditional form il mourrait [ilmuʁːɛ] ('he would die'), for example, contrasts with the imperfect form il mourait [ilmuʁɛ] ('he was dying'). Other verbs that have a double ⟨rr⟩ orthographically in the future and conditional are pronounced with a simple [ʁ]: il pourra ('he will be able to'), il verra ('he will see').

When the prefix in- combines with a base that begins with n, the resulting word is sometimes pronounced with a geminate [nː] and similarly for the variants of the same prefix im-, il-, ir-:

- inné [in(ː)e] ('innate')

- immortel [im(ː)ɔχtɛl] ('immortal')

- illisible [il(ː)izibl] ('illegible')

- irresponsable [iʁ(ː)ɛspɔ̃sabl] ('irresponsible')

Other cases of optional gemination can be found in words like syllabe ('syllable'), grammaire ('grammar'), and illusion ('illusion'). The pronunciation of such words, in many cases, a spelling pronunciation varies by speaker and gives rise to widely varying stylistic effects.[13] In particular, the gemination of consonants other than the liquids and nasals /m n l ʁ/ is "generally considered affected or pedantic".[14] Examples of stylistically marked pronunciations include addition [adːisjɔ̃] ('addition') and intelligence [ɛ̃telːiʒɑ̃s] ('intelligence').

Gemination of doubled 'm' and 'n' is typical of the Languedoc region, as opposed to other southern accents.

A few cases of gemination do not correspond to double consonant letters in the orthography.[15] The deletion of word-internal schwas (see below), for example, can give rise to sequences of identical consonants: là-dedans [laddɑ̃] ('inside'), l'honnêteté [lɔnɛtte] ('honesty'). Gemination is obligatory in such contexts. The elided form of the object pronoun l' ('him/her/it') can optionally (in nonstandard, popular speech) be realized as a geminate [lː] when it appears after a vowel:

- Je l'ai vu [ʒǝl(ː)evy] ('I saw it')

- Il faut l'attraper [ilfol(ː)atχape] ('it must be caught')

Finally, a word pronounced with emphatic stress can exhibit gemination of its first syllable-initial consonant:

- formidable [fːɔʁmidabl] ('terrific')

- épouvantable [epːuvɑ̃tabl] ('horrible')

Liaison

Many words in French can be analyzed as having a "latent" final consonant that is pronounced only in certain syntactic contexts when the next word begins with a vowel. For example, the word deux /dø/ ('two') is pronounced [dø] in isolation or before a consonant-initial word (deux jours /dø ʒuʁ/ → [døʒuːʁ] 'two days'), but in deux ans /døz‿ɑ̃/ ('two years'), the linking or liaison consonant /z/ is pronounced.

Vowels

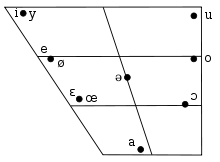

Unrounded vowels are shown to the left of the dots and rounded vowels to the right.

The speaker in question does not exhibit a contrast between /ɡ/ and /ɑ/.

Chart with audio

Standard French contrasts up to 13 oral vowels and up to 4 nasal vowels. The schwa (in the center of the diagram next to this paragraph) is not necessarily a distinctive sound. Even though it is often realised as other vowels, its patterning suggests that it is a separate phoneme (see the sub-section Schwa below).

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||||

| Close | oral | i | y | u | |

| Close-mid | ɥ | ø | ə | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ (ɛː) | œ | ɔ | ||

| nasal | ɛ̃ | (œ̃) | ɔ̃ | ||

| Open | ɑ̃ | ||||

| oral | a | (ɑ) | |||

Open vowels

The phonemic contrast between front /ɡ/ and back /ɑ/ is sometimes not maintained in Standard French, which leads some researchers to reject the idea of two distinct phonemes.[16] However, the distinction is still clearly maintained in other dialects such as Quebec French.[17]

While there is much variation among speakers in France, a number of general tendencies can be observed. First of all, the distinction is most often preserved in word-final stressed syllables such as in these minimal pairs:

- tache /taʃ/ → [taʃ] ('stain'), vs. tâche /tɑʃ/ → [tɑːʃ] ('task')

- rat /ʁa/ → [ʁa] ('rat'), vs. ras /ʁɑ/ → [ʁɑ] ('short').

There are certain environments that prefer one open vowel over the other. For example, /ɑ/ is preferred after /ʁw/ and before /z/:

The difference in quality is often reinforced by a difference in length (but the difference is contrastive in final closed syllables). The exact distribution of the two vowels varies greatly from speaker to speaker.[19]

Back /ɑ/ is much rarer in unstressed syllables, but it can be encountered in some common words:

Morphologically complex words derived from words containing stressed /ɑ/ do not retain it:

- âgé /ɑʒe/ → [ɑˑʒe] ('aged', from âge /ɑʒ/ → [ɑːʒ])

- rarissime /ʁaʁisim(ə)/ → [ʁaʁisim] ('very rare', from rare /ʁɑʁ/ → [ʁɑːʁ]).

Even in the final syllable of a word, back /ɑ/ may become [a] if the word in question loses its stress within the extended phonological context:[18]

- J'ai été au bois /ʒe ete o bwɑ/ → [ʒe.ete.obwa] ('I was in the woods'),

- J'ai été au bois de Vincennes /ʒe ete o bwɑ dǝvɛ̃sɛn/ → [ʒe.ete.obwadvɛ̃sɛn] ('I was in the Vincennes woods').

Mid vowels

| Vowel | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Orthography | Gloss | |

| Oral vowels | |||

| /i/ | /si/ | si | 'if' |

| /e/ | /fe/ | fée | 'fairy' |

| /ɛ/ | /fɛ/ | fait | 'does' |

| /ɛː/ | /fɛːt/ | fête | 'party' |

| /ə/ | /sə/ | ce | 'this'/'that' |

| /œ/ | /sœːʁ/ | sœur | 'sister' |

| /ø/ | /sø/ | ceux | 'those' |

| /y/ | /sy/ | su | 'known' |

| /u/ | /su/ | sous | 'under' |

| /o/ | /so/ | sot | 'silly' |

| /ɔ/ | /sɔːʁ/ | sort | 'fate' |

| /ɡ/ | /sa/ | sa | 'his'/'her', |

| /ɑ/ | /pɑːt/ | pâte | 'dough' |

| Nasal vowels | |||

| /ɑ̃/ | /sɑ̃/ | sans | 'without' |

| /ɔ̃/ | /sɔ̃/ | son | 'his' |

| /œ̃/ | /bʁœ̃/ | brun | 'brown' |

| /ɛ̃/[20] | /bʁɛ̃/ | brin | 'sprig' |

| Semi-vowels | |||

| /j/ | /jɛʁ/ | hier | 'yesterday' |

| /e/ | /plɥi/ | pluie | 'rain' |

| /w/ | /wi/ | oui | 'yes' |

Although the mid vowels contrast in certain environments, there is limited distributional overlap so they often appear in complementary distribution. Generally, close-mid vowels are found in open syllables, and open-mid vowels are found in closed syllables. However, there are minimal pairs:[21]

- open-mid /ɛ/ and close-mid /e/ contrast in final-position open syllables:

- likewise, open-mid /ɔ/ and /œ/ contrast with close-mid /o/ and /ø/ mostly in closed monosyllables, such as these:

- jeune [ʒœn] ('young'), vs. jeûne [ʒøːn] ('fast', verb),

- roc [ʁɔk] ('rock'), vs. rauque [ʁoːk] ('hoarse'),

- Rhodes [ʁɔd] ('Rhodes'), vs. rôde [ʁoːd] ('[I] lurk'),

- Paul [pɔl] ('Paul', masculine), vs. Paule [poːl] ('Paule', feminine),

- bonne [bɔn] ('good', feminine), vs. Beaune [boːn] ('Beaune', the city).

Beyond the general rule, known as the loi de position among French phonologists,[22] there are some exceptions. For instance, /o/ and /ø/ are found in closed syllables ending in [z], and only [ɔ] is found in closed monosyllables before [ʁ], [r], and [a].[23]

The phonemic opposition of /ɛ/ and /e/ has been lost in the southern half of France, where these two sounds are found only in complementary distribution. The phonemic oppositions of /ɔ/ and /o/ and of /œ/ and /ø/ in terminal open syllables have been lost in all of France, but not in Belgium, where pot and peau are still opposed as /pɔ/ and /po/.[24]

Nasal vowels

The phonetic qualities of the back nasal vowels are not very similar to those of the corresponding oral vowels, and the contrasting factor that distinguishes /ɑ̃/ and /ɔ̃/ is the extra lip rounding of the latter according to some linguists,[25] but other linguists have come to the conclusion that the main difference is in tongue height.[26] Speakers who produce both /œ̃/ and /ɛ̃/ distinguish them mainly through increased lip rounding of the former, but many speakers use only the latter phoneme, especially most speakers in northern France such as Paris (but not farther north, in Belgium).[25][26]

In some dialects, particularly that of Europe, there is an attested tendency for nasal vowels to shift in a counterclockwise direction: /ɛ̃/ tends to be more open and shifts toward the vowel space of /ɑ̃/ (realised also as [æ̃]), /ɑ̃/ rises and rounds to [ɔ̃] (realised also as [ɒ̃]) and /ɔ̃/ shifts to [õ] or [ũ]. Also, there also is an opposite movement for /ɔ̃/ for which it becomes more open and unrounds to [ɑ̃], resulting in a merger of Standard French /ɔ̃/ and /ɛ̃/ in this case.[26][27] In Quebec French, this shift has the clockwise direction: /ɛ̃/ → [ẽ], /ɑ̃/ → [ã], /ɔ̃/ → [õ].[28]

Schwa

When phonetically realised, schwa (/ə/), also called ⟨e⟩ caduc ('dropped ⟨e⟩') and ⟨e⟩ muet ('mute ⟨e⟩'), is a mid-central vowel with some rounding.[21] Many authors consider it to be phonetically identical to [œ].[29][30] Geoff Lindsey suggests the symbol ⟨ɵ⟩.[31][32] Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006) state, more specifically, that it merges with /ø/ before high vowels and glides:

- netteté /nɛtəte/ → [nɛtøte] ('clarity'),

in phrase-final stressed position:

- dis-le ! /di lə/ → [di.lø] ('say it'),

and that it merges with [œ] elsewhere.[33] However, some speakers make a clear distinction, and it exhibits special phonological behavior that warrants considering it a distinct phoneme. Furthermore, the merger occurs mainly in the French of France; in Quebec, /ø/ and /ə/ are still distinguished.[34]

The main characteristic of French schwa is its "instability": the fact that under certain conditions it has no phonetic realisation.

- That is usually the case when it follows a single consonant in a medial syllable:

- rappeler /ʁapəle/ → [ʁaple] ('to recall'),

- It is most frequently mute in word-final position:

- table /tabl(ə)/ → [tabl] ('table').

- Word-final schwas are optionally pronounced if preceded by two or more consonants and followed by a consonant-initial word:

- une porte fermée /yn(ə) pɔʁt(ə) fɛʁme/ → [ynpɔχt(ə)fɛʁme] ('a closed door').

- In the future and conditional forms of -er verbs, however, the schwa is sometimes deleted even after two consonants:

- tu garderais /ty ɡaʁdəʁɛ/ → [tyɡaʁd(ə)ʁɛ] ('you would guard'),

- nous brusquerons [les choses] /nu bʁyskəʁɔ̃/ → [nubʁysk(ə)ʁɔ̃] ('we will precipitate [things]').

- On the other hand, it is pronounced word-internally when it follows more pronounced consonants that cannot be combined into a complex onset with the initial consonants of the next syllable:

Pronouncing [ə] as [œ] is a way to emphasise the syllable. For instance, pronouncing biberon ('baby bottle') [bibœʁɔ̃] instead of [bibəʁɔ̃] is a way to draw attention to the e (to clarify the spelling, for example).

In French versification, word-final schwa is always elided before another vowel and at the ends of verses. It is pronounced before a following consonant-initial word.[36] For example, une grande femme fut ici [yn(ə) ɡʁɑ̃d(ə) fam(ə) fyt‿isi], would be pronounced [ynəɡʁɑ̃dəfaməfytisi], with the /ə/ at the end of each word being pronounced.

Schwa cannot normally be realised as a front vowel ([œ]) in closed syllables. In such contexts in inflectional and derivational morphology, schwa usually alternates with the front vowel /ɛ/:

- harceler /aʁsəle/ → [aχsœle] ('to harass'), with

- [il] harcèle /aʁsɛl/ → [aχsɛl] ('[he] harasses').[37]

A three-way alternation can be observed, in a few cases, for a number of speakers:

- appeler /apəle/ → [ap(œ)le] ('to call'),

- j'appelle /ʒ‿apɛl/ → [ʒapɛl] ('I call'),

- appellation /apelasjɔ̃/ → [apelasjɔ̃] ('brand'), which can also be pronounced [apɛ(l)lasjɔ̃].[38]

Instances of orthographic ⟨e⟩ that do not exhibit the behaviour described above may be better analysed as corresponding to the stable, full vowel /œ/. The enclitic pronoun le, for example, always keeps its vowel in contexts like donnez-le-moi /dɔne lə mwa/ → [dɔnelœmwa] ('give it to me') for which schwa deletion would normally apply, and it counts as a full syllable for the determination of stress.

Cases of word-internal stable ⟨e⟩ are more subject to variation among speakers, but, for example, un rebelle /ɛ̃ ʁəbɛl/ → [ɛ̃ʁœbɛl] ('a rebel') must be pronounced with a full vowel in contrast to un rebond /ɛ̃ ʁəbɔ̃/ → [ɛ̃ːʁœbɔ̃] or [ɛ̃ʁbɔ̃] ('a bounce').[39]

Length

Except for the distinction still made by some speakers between /ɛ/ and /ɛː/ in rare minimal pairs like mettre [mɛtχ] ('to put') vs. maître [mɛːtχ] ('teacher'), variation in vowel length is entirely allophonic. Vowels can be lengthened in closed, stressed syllables, under the following two conditions:

- /o/, /ø/, /ɑ/, and the nasal vowels are lengthened before any consonant: pâte [pɑːt] ('dough'), chante [ʃɑ̃ːt] ('sings').

- All vowels are lengthened if followed by one of the consonants /v/, /z/, /ʒ/, /ʁ/ (not in combination), or by the cluster /vʁ/: mer/mère [mɛːʁ] ('sea/mother'), crise [kχiːz] ('crisis'), livre [liːvʁ] ('book').[40] However, words such as (ils) servent [sɛʁv] ('(they) serve') or tarte [taχt] ('pie') are pronounced with short vowels since the /ʁ/ appears in clusters other than /vʁ/.

When such syllables lose their stress, the lengthening effect may be absent. The vowel [o] of saute is long in Regarde comme elle saute! In which it is final but not in Qu'est-ce qu'elle saute bien!.[41] In the latter case, the vowel is unstressed because it is not phrase-final. An exception occurs, however, with the phoneme /ɛː/ because of its distinctive nature, provided it is word-final, as in C'est une fête importante which fête is pronounced with long /ɛː/ despite being unstressed in that position.[41]

The following table presents the pronunciation of a representative sample of words in phrase-final (stressed) position:

| phoneme | vowel value in closed syllable | vowel value in open syllable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-lengthening consonant | lengthening consonant | |||||

| /i/ | habite | [a.bit] | livre | [liːvʁ] | habit | [a.bi] |

| /e/ | — | été | [e.te] | |||

| /ɛ/ | faites | [fɛt] | faire | [fɛːʁ] | fait | [fɛ] |

| /ɛː/ | fête | [fɛːt] | rêve | [ʁɛːv] | — | |

| /œ/ | jeune | [ʒœn] | œuvre | [œːvʁ] | — | |

| /ə/ | — | le | [lə] | |||

| /ø/ | jeûne | [ʒøːn] | joyeuse | [ʒwa.jøːz] | joyeux | [ʒwa.jø] |

| /y/ | débute | [de.byt] | juge | [ʒyːʒ] | début | [de.by] |

| /u/ | bourse | [buχs] | bouse | [buːz] | bout | [bu] |

| /o/ | saute | [soːt] | rose | [ʁoːz] | saut | [so] |

| /ɔ/ | sotte | [sɔt] | mort | [mɔːʁ] | — | |

| /ɡ/ | rate | [ʁat] | rage | [ʁaːʒ] | rat | [ʁa] |

| /ɑ/ | appâte | [a.pɑːt] | rase | [ʁɑːz] | appât | [a.pɑ] |

| /ɑ̃/ | pende | [pɑ̃ːd] | genre | [ʒɑ̃ːʁ] | pends | [pɑ̃] |

| /ɔ̃/ | réponse | [ʁe.pɔ̃ːs] | éponge | [e.pɔ̃ːʒ] | réponds | [ʁe.pɔ̃] |

| /œ̃/ | emprunte | [ɑ̃.pχœ̃ːt] | grunge | [ɡʁœ̃ːʒ] | emprunt | [ɑ̃.pχœ̃] |

| /ɛ̃/ | teinte | [tɛ̃ːt] | quinze | [kɛ̃ːz] | teint | [tɛ̃] |

In the examples above, the final [ə] (shown in parentheses) is elided when preceding a vowel-initial word; similarly, it is deleted when preceding a word beginning with a consonant cluster. Also, if the following word begins in a consonant cluster and the first consonant is distinct from the final consonant of the previous word, the second last syllable of the previous word is long. Otherwise, the syllables are separated by a schwa and the vowel of the second last syllable is short.

Elision

The final vowel (usually /ə/) of a number of monosyllabic function words is elided in syntactic combinations with a following word that begins with a vowel. For example, compare the pronunciation of the unstressed subject pronoun, in je dors /ʒə dɔʁ/ [ʒə.dɔʁ] ('I am sleeping'), and in j'arrive /ʒ‿aʁiv/ [ʒa.ʁiv] ('I am arriving').

Glides and diphthongs

The glides [j], [w], and [e] appear in syllable onsets immediately followed by a full vowel. In many cases, they alternate systematically with their vowel counterparts [ũ], [u], and [y] such as in the following pairs of verb forms:

The glides in the examples can be analysed as the result of a glide formation process that turns an underlying high vowel into a glide when followed by another vowel: /nie/ → [nje].

This process is usually blocked after a complex onset of the form obstruent + liquid (a stop or a fricative followed by /l/ or /ʁ/). For example, while the pair loue/louer shows an alternation between [u] and [w], the same suffix added to cloue [klu], a word with a complex onset, does not trigger the glide formation: clouer [klue] ('to nail') Some sequences of glide + vowel can be found after obstruent-liquid onsets, however. The main examples are [ɥi], as in pluie [plɥi] ('rain'), [wa], and [wɛ̃].[42] They can be dealt with in different ways, aa by adding appropriate contextual conditions to the glide formation rule or by assuming that the phonemic inventory of French includes underlying glides or rising diphthongs like /ɥi/ and /wa/.[43][44]

Glide formation normally does not occur across morpheme boundaries in compounds like semi-aride ('semi-arid').[45] However, in colloquial registers, si elle [siɛl] ('if she') can be pronounced just like ciel [sjɛl] ('sky'), or tu as [tyɑ] ('you have') like tua [tɥa] ('[he] killed').[46]

The glide [j] can also occur in syllable coda position, after a vowel, as in soleil [sɔlɛj] ('sun'). There again, one can formulate a derivation from an underlying full vowel /i/, but the analysis is not always adequate because of the existence of possible minimal pairs like pays [pɛi] ('country') / paye [pɛj] ('paycheck') and abbaye [abɛi] ('abbey') / abeille [abɛj] ('bee').[47] Schane (1968) proposes an abstract analysis deriving postvocalic [j] from an underlying lateral by palatalization and glide conversion (/li/ → /ʎ/ → /j/).[48]

Stress

Word stress is not distinctive in French so two words cannot be distinguished on the basis of stress placement alone. In fact, grammatical stress is always on the final full syllable of a French word (the final syllable with a vowel other than schwa). Monosyllables with schwa as their only vowel (ce, de, que, etc.) are generally unstressed clitics but rarely may receive stress.[29]

The difference between stressed and unstressed syllables in French is less marked than in English. Vowels in unstressed syllables keep their full quality, giving rise to a syllable-timed rhythm (see Isochrony). Moreover, words lose their stress to varying degrees when pronounced in phrases and sentences. In general, only the last word in a phonological phrase retains its full grammatical stress (on its last syllable unless this is a schwa).[49]

Emphatic stress

Emphatic stress is used to call attention to a specific element in a given context such as to express a contrast or to reinforce the emotive content of a word. In French, this stress falls on the first consonant-initial syllable of the word in question. The characteristics associated with emphatic stress include increased amplitude and pitch of the vowel and gemination of the onset consonant, as mentioned above.[50]

- C'est parfaitement vrai. [sɛpaχfɛtmɑ̃ˈvʁɛ] ('It's perfectly true.' No emphatic stress)

- C'est parfaitement vrai. [sɛ(p)ˈpaχfɛtmɑ̃vʁɛ] (emphatic stress on parfaitement)

For words that begin with a vowel, emphatic stress falls on the first syllable that begins with a consonant or on the initial syllable with the insertion of a glottal stop or a liaison consonant.

- C'est épouvantable. [sɛte(p)ˈpuvɑ̃tabl] ('It's terrible.' Emphatic stress on second syllable of épouvantable)

- C'est épouvantable [sɛ(t)ˈtepuvɑ̃tabl] (initial syllable with liaison consonant [t])

- C'est épouvantable [sɛˈʔepuvɑ̃tabl] (initial syllable with glottal stop insertion)

Intonation

French intonation differs substantially from that of English.[51] There are four primary patterns:

- The continuation pattern is a rise in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a rhythm group (typically a phrase).

- The finality pattern is a sharp fall in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a declarative statement.

- The yes/no intonation is a sharp rise in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a yes/no question.

- The information question intonation is a rapid fall-off from high pitch on the first word of a non-yes/no question, often followed by a small rise in pitch on the last syllable of the question.

See also

- History of French

- Phonological history of French

- Varieties of French

- French orthography

- Reforms of French orthography

- Phonologie du Français Contemporain

- Quebec French phonology

References

- ↑ Map based on Trudgill (1974:221)

- 1 2 Fougeron & Smith (1993:79)

- 1 2 3 Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:192)

- ↑ Adams (1975:288)

- ↑ Phonological Variation in French: Illustrations from Three Continents, edited by Randall Scott Gess, Chantal Lyche, Trudel Meisenburg.

- ↑ Wells (1989:44)

- ↑ Grevisse & Goosse (2011, §32, b)

- 1 2 Fougeron & Smith (1993:75)

- ↑ Grevisse & Goosse (2011, §33, b), Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:47)

- ↑ Recasens (2013:11–13)

- ↑ Fougeron & Smith (1993:74–75)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:149–150)

- ↑ Yaguello (1991), cited in Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:51)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:150)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:151–153)

- ↑ "Some phoneticians claim that there are two distinct as in French, but evidence from speaker to speaker and sometimes within the speech of a single speaker is too contradictory to give empirical support to this claim".Casagrande (1984:20)

- ↑ Postériorisation du / a /

- 1 2 Tranel (1987:64)

- ↑ "For example, some have the front [a] in casse 'breaks', and the back [ɑ] in tasse 'cup', but for others the reverse is true. There are also, of course, those who use the same vowel, either [a] or [ɑ], in both words".Tranel (1987:48)

- ↑ //John C. Wells// prefers the symbol /æ̃/, as the vowel has become more open in recent times: http://phonetic-blog.blogspot.com/2010/07/french-nasalized-vowels.html

- 1 2 Fougeron & Smith (1993:73)

- ↑ Morin (1986)

- ↑ Léon (1992:?)

- ↑ Kalmbach, Jean-Michel (2011). "Phonétique et prononciation du français pour apprenants finnophones". Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 Fougeron & Smith (1993:74)

- 1 2 3 Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins 2006, p. 33-34.

- ↑ Hansen, Anita Berit (1998). Les voyelles nasales du français parisien moderne. Aspects linguistiques, sociolinguistiques et perceptuels des changements en cours (in French). Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-495-4.

- ↑ Oral articulation of nasal vowel in French

- 1 2 Anderson (1982:537)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:88)

- ↑ Lindsey, Geoff. "Le FOOT vowel". English Speech Services. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Lindsey, Geoff. "Rebooting Buttocks". English Speech Services. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:59)

- ↑ Timbre du schwa en français et variation régionale : un étude comparative retrieved 14 July 2013

- ↑ Tranel (1987:88–105)

- ↑ Casagrande (1984:228–29)

- ↑ Anderson (1982:544–46)

- ↑ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:63) for [e], TLFi, s.v. appellation for [ɛ].

- ↑ Tranel (1987:98–99)

- ↑ Walker (1984:25–27), Tranel (1987:49–51)

- 1 2 Walker (2001:46)

- ↑ The latter two correspond to orthographic ⟨oi⟩, as in trois [tχwa] ('three'), which contrasts with disyllabic troua [tχua] ('[he] punctured').

- ↑ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:37–39)

- ↑ Chitoran (2002:206)

- ↑ Chitoran & Hualde (2007:45)

- ↑ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:39)

- ↑ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:39). The words pays and abbaye are more frequently pronounced [pei] and [abei].

- ↑ Schane (1968:57–60)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:194–200)

- ↑ Tranel (1987:200–201)

- ↑ Lian (1980)

Sources

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1975), "The Distribution of Retracted Sibilants in Medieval Europe", Language, Linguistic Society of America, 51 (2): 282–292, doi:10.2307/412855, JSTOR 412855

- Anderson, Stephen R. (1982), "The Analysis of French Shwa: Or, How to Get Something for Nothing", Language, 58 (3): 534–573, doi:10.2307/413848, JSTOR 413848

- Casagrande, Jean (1984), The Sound System of French, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, ISBN 0-87840-085-0

- Chitoran, Ioana; Hualde, José Ignacio (2007), "From hiatus to diphthong: the evolution of vowel sequences in Romance", Phonology, 24: 37–75, doi:10.1017/S095267570700111X

- Chitoran, Ioana (2002), "A perception-production study of Romanian diphthongs and glide-vowel sequences", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 32 (2): 203–222, doi:10.1017/S0025100302001044

- Fagyal, Zsuzsanna; Kibbee, Douglas; Jenkins, Fred (2006). French: a linguistic introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82144-4.

- Fougeron, Cecile; Smith, Caroline L (1993), "Illustrations of the IPA:French", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 23 (2): 73–76, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004874

- Grevisse, Maurice; Goosse, André (2011). Le Bon usage (in French). Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Duculot. ISBN 978-2-8011-1642-5.

- Léon, P. (1992), Phonétisme et prononciations du français, Paris: Nathan

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19814-8.

- Lian, A-P (1980), Intonation Patterns of French (PDF), Melbourne: River Seine Publications, ISBN 0-909367-21-3

- Morin, Yves-Charles (1986), "La loi de position ou de l'explication en phonologie historique", Revue québécoise de linguistique, 15: 199–231

- Recasens, Daniel (2013), "On the articulatory classification of (alveolo)palatal consonants", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 1–22, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000199

- Schane, Sanford A. (1968), French Phonology and Morphology, Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, ISBN 0-262-19040-0

- Tranel, Bernard (1987), The Sounds of French: An Introduction, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31510-7

- Walker, Douglas (2001), French Sound Structure, University of Calgary Press, ISBN 1-55238-033-5

- Wells, J.C. (1989), "Computer-Coded Phonemic Notation of Individual Languages of the European Community", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 19 (1): 31–54, doi:10.1017/S0025100300005892

- Yaguello, Marina (1991), "Les géminées de M. Rocard", En écoutant parler la langue, Paris: Seuil, pp. 64–70

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French pronunciation. |

- Foreign Service Institute's freely downloadable course on French phonology from their extensive Language Materials:

- Large collection of recordings of French words

- mp3 Audio Pronunciation of French vowels, consonants and alphabet

- French Vowels Demonstrated by a Native Speaker (youtube)

- French Consonants Demonstrated by a Native Speaker (youtube)