Elliptic divisibility sequence

In mathematics, an elliptic divisibility sequence (EDS) is a sequence of integers satisfying a nonlinear recursion relation arising from division polynomials on elliptic curves. EDS were first defined, and their arithmetic properties studied, by Morgan Ward[1] in the 1940s. They attracted only sporadic attention until around 2000, when EDS were taken up as a class of nonlinear recurrences that are more amenable to analysis than most such sequences. This tractability is due primarily to the close connection between EDS and elliptic curves. In addition to the intrinsic interest that EDS have within number theory, EDS have applications to other areas of mathematics including logic and cryptography.

Definition

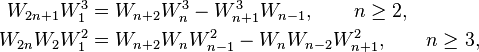

A (nondegenerate) elliptic divisibility sequence (EDS) is a sequence of integers (Wn)n ≥ 1 defined recursively by four initial values W1, W2, W3, W4, with W1W2W3 ≠ 0 and with subsequent values determined by the formulas

It can be shown that if W1 divides each of W2, W3, W4 and if further W2 divides W4, then every term Wn in the sequence is an integer.

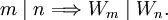

Divisibility property

An EDS is a divisibility sequence in the sense that

In particular, every term in an EDS is divisible by W1, so EDS are frequently normalized to have W1 = 1 by dividing every term by the initial term.

Any three integers b, c, d with d divisible by b lead to a normalized EDS on setting

It is not obvious, but can be proven, that the condition b | d suffices to ensure that every term in the sequence is an integer.

General recursion

A fundamental property of elliptic divisibility sequences is that they satisfy the general recursion relation

(This formula is often applied with r = 1 and W1 = 1.)

Nonsingular EDS

The discriminant of a normalized EDS is the quantity

An EDS is nonsingular if its discriminant is nonzero.

Examples

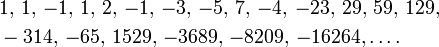

A simple example of an EDS is the sequence of natural numbers 1, 2, 3,… . Another interesting example is the sequence 1, 3, 8, 21, 55, 144, 377, 987,… consisting of every other term in the Fibonacci sequence, starting with the second term. However, both of these sequences satisfy a linear recurrence and both are singular EDS. An example of a nonsingular EDS is

Periodicity of EDS

A sequence (An)n ≥ 1 is said to be periodic if there is a number N ≥ 1 so that An+N = An for every n ≥ 1. If a nondegenerate EDS (Wn)n ≥ 1 is periodic, then one of its terms vanishes. The smallest r ≥ 1 with Wr = 0 is called the rank of apparition of the EDS. A deep theorem of Mazur[2] implies that if the rank of apparition of an EDS is finite, then it satisfies r ≤ 10 or r = 12.

Elliptic curves and points associated to EDS

Ward proves that associated to any nonsingular EDS (Wn) is an elliptic curve E/Q and a point P ε E(Q) such that

Here ψn is the n division polynomial of E; the roots of ψn are the nonzero points of order n on E. There is a complicated formula[3] for E and P in terms of W1, W2, W3, and W4.

There is an alternative definition of EDS that directly uses elliptic curves and yields a sequence which, up to sign, almost satisfies the EDS recursion. This definition starts with an elliptic curve E/Q given by a Weierstrass equation and a nontorsion point P ε E(Q). One writes the x-coordinates of the multiples of P as

Then the sequence (Dn) is also called an elliptic divisibility sequence. It is a divisibility sequence, and there exists an integer k so that the subsequence ( ±Dnk )n ≥ 1 (with an appropriate choice of signs) is an EDS in the earlier sense.

Growth of EDS

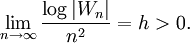

Let (Wn)n ≥ 1 be a nonsingular EDS that is not periodic. Then the sequence grows quadratic exponentially in the sense that there is a positive constant h such that

The number h is the canonical height of the point on the elliptic curve associated to the EDS.

Primes and primitive divisors in EDS

It is conjectured that a nonsingular EDS contains only finitely many primes[4] However, all but finitely many terms in a nonsingular EDS admit a primitive prime divisor.[5] Thus for all but finitely many n, there is a prime p such that p divides Wn, but p does not divide Wm for all m < n. This statement is an analogue of Zsigmondy's theorem.

EDS over finite fields

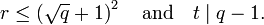

An EDS over a finite field Fq, or more generally over any field, is a sequence of elements of that field satisfying the EDS recursion. An EDS over a finite field is always periodic, and thus has a rank of apparition r. The period of an EDS over Fq then has the form rt, where r and t satisfy

More precisely, there are elements A and B in Fq* such that

The values of A and B are related to the Tate pairing of the point on the associated elliptic curve.

Applications of EDS

Bjorn Poonen[6] has applied EDS to logic. He uses the existence of primitive divisors in EDS on elliptic curves of rank one to prove the undecidability of Hilbert's tenth problem over certain rings of integers.

Katherine Stange[7] has applied EDS and their higher rank generalizations called elliptic nets to cryptography. She shows how EDS can be used to compute the value of the Weil and Tate pairings on elliptic curves over finite fields. These pairings have numerous applications in pairing-based cryptography.

References

- ↑ Morgan Ward, Memoir on elliptic divisibility sequences, Amer. J. Math. 70 (1948), 31–74.

- ↑ B. Mazur. Modular curves and the Eisenstein ideal, Inst. Hautes Études Sci. Publ. Math. 47:33–186, 1977.

- ↑ This formula is due to Ward. See the appendix to J. H. Silverman and N. Stephens. The sign of an elliptic divisibility sequence. J. Ramanujan Math. Soc., 21(1):1–17, 2006.

- ↑ M. Einsiedler, G. Everest, and T. Ward. Primes in elliptic divisibility sequences. LMS J. Comput. Math., 4:1–13 (electronic), 2001.

- ↑ J. H. Silverman. Wieferich's criterion and the abc-conjecture. J. Number Theory, 30(2):226–237, 1988.

- ↑ B. Poonen. Using elliptic curves of rank one towards the undecidability of Hilbert's tenth problem over rings of algebraic integers. In Algorithmic number theory (Sydney, 2002), volume 2369 of Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., pages 33–42. Springer, Berlin, 2002.

- ↑ K. Stange. The Tate pairing via elliptic nets. In Pairing-Based Cryptography (Tokyo, 2007), volume 4575 of Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci. Springer, Berlin, 2007.

Further material

- G. Everest, A. van der Poorten, I. Shparlinski, and T. Ward. Recurrence sequences, volume 104 of Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2003. ISBN 0-8218-3387-1. (Chapter 10 is on EDS.)

- R. Shipsey. Elliptic divisibility sequences. PhD thesis, Goldsmith's College (University of London), 2000.

- K. Stange. Elliptic nets. PhD thesis, Brown University, 2008.

- C. Swart. Sequences related to elliptic curves. PhD thesis, Royal Holloway (University of London), 2003.

External links

- Graham Everest's EDS web page.

- Prime Values of Elliptic Divisibility Sequences.

- Lecture on p-adic Properites of Elliptic Divisibility Sequences.