V for Vendetta

| V for Vendetta | |

|---|---|

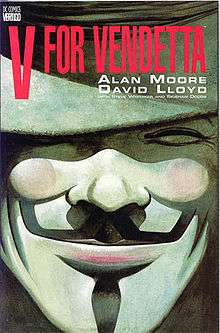

V for Vendetta collected edition cover, art by David Lloyd | |

| Publisher |

UK |

| Creative team | |

| Writer | Alan Moore |

| Artists |

|

| Letterer | Steve Craddock |

| Colourist |

Steve Whitaker Siobhan Dodds David Lloyd |

| Editor |

|

| Original publication | |

| Issues | 10 |

| Date of publication | September 1988 – May 1989 |

| ISBN | 0-930289-52-8 |

V for Vendetta is a graphic novel written by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Lloyd (with additional art by Tony Weare), published by DC Comics. Later versions were published by Vertigo, an imprint of DC Comics. The story depicts a dystopian and post-apocalyptic near-future history version of the United Kingdom in the 1990s, preceded by a nuclear war in the 1980s which had devastated most of the rest of the world. The fascist Norsefire party has exterminated its opponents in concentration camps and rules the country as a police state. The comics follow its title character and protagonist, V, an anarchist revolutionary dressed in a Guy Fawkes mask, as he begins an elaborate and theatrical revolutionist campaign to kill his former captors, bring down the fascist state and convince the people to bring about democratic government, while inspiring a young woman, Evey Hammond, to be his protégé.

Warner Bros. released a film adaptation of the same title in 2006.

Publication history

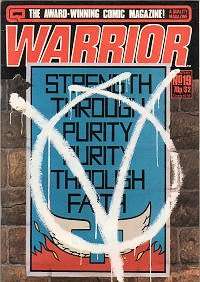

The first episodes of V for Vendetta appeared in black-and-white between 1982 and 1985, in Warrior, a British anthology comic published by Quality Communications. The strip was one of the least popular in that title; editor/publisher Dez Skinn remarked, "If I’d have given each character their own title, the failures would have certainly outweighed the successes, with the uncompromising “V for Vendetta” probably being an early casualty. But with five or six strips an issue, regular [readers] only needed two or three favorites to justify their buying the title."[1]

When the publishers cancelled Warrior in 1985 (with two completed issues unpublished due to the cancellation), several companies attempted to convince Moore and Lloyd to let them publish and complete the story. In 1988, DC Comics published a ten-issue series that reprinted the Warrior stories in colour, then continued the series to completion. The first new material appeared in issue No. 7, which included the unpublished episodes that would have appeared in Warrior No. 27 and No. 28. Tony Weare drew one chapter ("Vincent") and contributed additional art to two others ("Valerie" and "The Vacation"); Steve Whitaker and Siobhan Dodds worked as colourists on the entire series.

The series, including Moore's "Behind the Painted Smile" essay and two "interludes" outside the central continuity, then appeared in collected form as a trade paperback, published in the US by DC's Vertigo imprint (ISBN 0-930289-52-8) and in the UK by Titan Books (ISBN 1-85286-291-2).

Background

David Lloyd's paintings for V for Vendetta in Warrior first appeared in black and white. The DC Comics version published the artwork "colorised" in pastels. Lloyd has stated that he had always intended the artwork to appear in color, and that the initial publication in black and white occurred for financial reasons because color would have cost too much (although Warrior editor/publisher Dez Skinn expressed surprise at this information, as he had commissioned the strip in black and white and never intended Warrior to feature any interior color, irrespective of expense).

In writing V for Vendetta, Moore drew upon an idea for a strip titled The Doll, which he had submitted in 1975 at the age of 22 to DC Thomson. In "Behind the Painted Smile",[2] Moore revealed that the idea was rejected as DC Thomson balked at the idea of a "transsexual terrorist". Years later, Skinn allegedly invited Moore to create a dark mystery strip with artist David Lloyd.[3] He actually asked David Lloyd to recreate something similar to their popular Marvel UK Night Raven strip, a story with an enigmatic masked vigilante set in the United States in the 1930s. Lloyd asked for writer Alan Moore to join him, and the setting developed through their discussions, moving from the 1930s United States to a near-future Britain. As the setting progressed, so did the character's development; once conceived as a "realistic" gangster-age version of Night-Raven, he became, first, a policeman rebelling against the totalitarian state he served, then a heroic anarchist.

Moore and Lloyd conceived the series as a dark adventure-strip influenced by British comic characters of the 1960s, as well as by Night Raven,[4] which Lloyd had previously worked on with writer Steve Parkhouse. Editor Dez Skinn came up with the name "Vendetta" over lunch with his work colleague Graham Marsh — but quickly rejected it as sounding too Italian (in fact the word "vendetta" is Italian in origin). Then V for Vendetta emerged, putting the emphasis on "V" rather than "Vendetta". David Lloyd developed the idea of dressing V as Guy Fawkes after previous designs followed the conventional superhero look.

During the preparation of the story, Moore made a list of what he wanted to bring into the plot, which he reproduced in "Behind the Painted Smile":

Orwell. Huxley. Thomas Disch. Judge Dredd. Harlan Ellison's "Repent, Harlequin!" Said the Ticktockman, Catman and The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World by the same author. Vincent Price's Dr. Phibes and Theatre of Blood. David Bowie. The Shadow. Night Raven. Batman. Fahrenheit 451. The writings of the New Worlds school of science fiction. Max Ernst's painting "Europe After the Rain". Thomas Pynchon. The atmosphere of British Second World War films. The Prisoner. Robin Hood. Dick Turpin...[2]

The influence of such a wide number of references has been thoroughly proved in academic studies,[5] above which dystopian elements stand out, especially the similarity with George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four in several stages of the plot.[6]

The political climate of Britain in the early 1980s also influenced the work,[7] with Moore positing that Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government would "obviously lose the 1983 elections", and that an incoming Michael Foot-led Labour government, committed to complete nuclear disarmament, would allow the United Kingdom to escape relatively unscathed after a limited nuclear war. However, Moore felt that fascists would quickly subvert a post-holocaust Britain.[2] Moore's scenario remains untested. Addressing historical developments when DC reissued the work, he noted:

Naïveté can also be detected in my supposition that it would take something as melodramatic as a near-miss nuclear conflict to nudge Britain towards fascism... The simple fact that much of the historical background of the story proceeds from a predicted Conservative defeat in the 1983 General Election should tell you how reliable we were in our roles as Cassandras.[8]

The February 1999 issue of The Comics Journal ran a poll on "The Top 100 (English-Language) Comics of the Century": V for Vendetta reached 83rd place.[9]

Plot

Book 1: Europe After the Reign

On Guy Fawkes Night in London in 1997, a financially desperate 16-year-old, Evey Hammond, sexually solicits men who are actually members of the state secret police, called "The Finger". Preparing to rape and kill her, the Fingermen are dispatched by V, a cloaked anarchist wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, who later remotely detonates explosives at the Houses of Parliament before bringing Evey to his contraband-filled underground lair, the "Shadow Gallery". Evey tells V her life story, which reveals that a global nuclear war in the late 1980s has since triggered the rise of England's fascist government, Norsefire.

Meanwhile, Eric Finch, a veteran detective in charge of the regular police force—"the Nose"—begins investigating V's terrorist activities. Finch often communicates with Norsefire's other intelligence departments, including "the Finger," led by Derek Almond, and "the Head", embodied by Adam Susan: the reclusive government Leader, who obsessively oversees the government's Fate computer system. Finch's case thickens when V mentally deranges Lewis Prothero, a propaganda-broadcasting radio personality; forces the suicide of Bishop Anthony Lilliman, a Paedophile priest; and prepares to murder Dr. Delia Surridge, a medical researcher who once had a romance with Finch. Finch suddenly discovers the connection among V's three targets: they all used to work at a former Norsefire "resettlement camp" near Larkhill. That night, V kills both Almond and Surridge, but Surridge has left a diary revealing that V—a former inmate and victim of Surridge's cruel medical experiments—was able to destroy and flee the camp, and is now eliminating the camp's former officers for what they did at the camp. Finch reports these findings to Susan, who suspects that this vendetta may actually be a cover for V, who, he worries, may be plotting an even bigger terrorist attack.

Book 2: This Vicious Cabaret

Four months later, V breaks into Jordan Tower, the home of Norsefire's propaganda department, "the Mouth"—led by Roger Dascombe—to broadcast a speech that calls on the people to resist the government. V escapes using an elaborate diversion that results in Dascombe's death. Finch is soon introduced to Peter Creedy, the new head of the Finger, who provokes Finch to strike him and thus get sent on a forced vacation. All this time, Evey has moved on with her life, becoming romantically involved with a much older man named Gordon. Evey and Gordon unknowingly cross paths with Rose Almond, the widow of the recently killed Derek. After Derek's death, Rose reluctantly began a relationship with Dascombe, but now, with both of her lovers murdered, she is forced to perform demoralizing burlesque work, increasing her hatred of the unsupportive government.

When a Scottish gangster named Ally Harper murders Gordon, a vengeful Evey interrupts a meeting between Harper and Creedy, the latter of whom is buying the support of Harper's thugs in preparation for a coup d'état. Evey attempts to shoot Harper, but is suddenly abducted and then imprisoned. Amidst interrogation and torture, Evey finds an old letter hidden in her cell by an inmate named Valerie Page, a film actress who was imprisoned and executed for being a lesbian. Evey's interrogator finally gives her a choice of collaboration or death; inspired by Valerie, Evey refuses to collaborate, and, expecting to be executed, is instead told that she is free. Stunned, Evey learns that her supposed imprisonment is in fact a hoax constructed by V so that she could experience an ordeal similar to the one that shaped him at Larkhill. He reveals that Valerie was a real Larkhill prisoner who died in the cell next to his and that the letter is not a fake. Evey forgives V, who has hacked into the government's Fate computer system and started emotionally manipulating Adam Susan with mind games. Consequently, Susan, who has formed a bizarre romantic attachment to the computer, is beginning to descend into madness.

Book 3: The Land of Do-As-You-Please

The following 5 November (1998), V blows up the Post Office Tower and Jordan Tower, killing "the Ear" leader Brian Etheridge; in addition to effectively shutting down three government agencies: the Eye, the Ear, and the Mouth. Creedy's men and Harper's associated street gangs violently suppress the subsequent wave of revolutionary fervor from the public. V notes to Evey that he has not yet achieved what he calls the "Land of Do-as-You-Please", meaning a functional anarchistic society, and considers the current chaotic situation an interim period of "Land of Take-What-You-Want". Finch has been mysteriously absent and his young assistant, Dominic Stone, one day realises that V has been influencing the Fate computer all along, which would explain V's consistent foresight. All the while, Finch has been travelling to the abandoned site of Larkhill, where he takes LSD to conjure up memories of his own devastated past and to put his mind in the role of a prisoner of Larkhill, like V, to help give him an intuitive understanding of V's experiences. Returning to London, Finch suddenly deduces that V's lair is inside the abandoned Victoria Station, which he enters.

V takes Finch by surprise; resulting in a scuffle which sees Finch shoot V and V wound Finch with a knife. V claims that he cannot be killed since he is only an idea and that "ideas are bulletproof"; regardless, V is indeed mortally wounded and returns to the Shadow Gallery deeper within, dying in Evey's arms. Evey considers unmasking V, but decides not to, realising that V is not an identity but a symbol. She then assumes V's identity, donning one of his spare Guy Fawkes costumes. Finch sees the large amount of blood that V has left in his wake and deduces that he has mortally wounded V. Occurring concurrently to this; Creedy has been pressuring Susan to appear in public, hoping to leave him exposed. Sure enough, as Susan stops to shake hands with Rose during a parade, she shoots him in the head in vengeance for the death of her husband and the life she has had to lead since then. Following Rose's arrest, Creedy assumes emergency leadership of the country, and Finch emerges from the subway proclaiming V's death.

Due to his LSD-induced epiphany, Finch leaves his position within "the Nose". The power struggle between the remaining leaders' results in all of their deaths; with Harper betraying and killing Creedy at the behest of Helen Heyer (wife of "the Eye" leader Conrad Heyer; who had outbid Creedy for Harper's loyalty), and Harper and Heyer killing each other as a consequence of Heyer's attack on Harper following his discovery of Harper's affair with his wife. With the fate of the top government officials' unknown to the public, Stone acts as leader of the police forces deployed to ensure that the riots are contained should V still be alive and make his promised public announcement. Evey appears to a crowd, dressed as V, announcing the destruction of 10 Downing Street the following day and telling the crowd they must "...choose what comes next. Lives of your own, or a return to chains", whereupon a general insurrection begins. Evey destroys 10 Downing Street[10] by blowing up an Underground train containing V's body, in the style of an explosive Viking funeral. She abducts Stone, apparently to train him as her successor. The book ends with Finch quietly observing the chaos raging in the city and walking down an abandoned motorway whose lights have all gone out.

Characters

V

V is a masked anarchist who seeks to systematically kill the leaders of Norsefire, a fascist dictatorship ruling a dystopian United Kingdom. He is well-versed in the arts of explosives, subterfuge, and computer hacking, and has a vast literary, cultural and philosophical intellect. V is the only survivor of an experiment in which four dozen prisoners were given injections of a compound called Batch 5. The compound caused vast cellular anomalies that eventually killed all of the subjects except V, who developed advanced strength, reflexes, endurance and pain tolerance. Throughout the novel, V almost always wears his trademark Guy Fawkes mask, a shoulder-length wig of straight dark-brown hair and an outfit consisting of black gloves, tunic, trousers and boots. When not wearing the mask, his face is not shown. When outside the Shadow Gallery, he completes this ensemble with a circa-17th century conical hat and floor-length cloak. His weapons of choice include daggers, explosives and tear gas.

The book suggests that V took his name from the Roman numeral "V", the number of the room he was held in during the experiment.

Evey Hammond

Evey "Eve" Hammond is a sixteen-year-old (seventeen-year-old as of Book 2) whom V saves from the Fingermen. The novel details her life's story: how she lost every person she ever loved due to the Norsefire party and its criminal connections, how she met V and grew to understand him and, finally, how she became his successor.

Adam Susan

Adam Susan, also known as the "Leader", is the dictator of the Norsefire Party and its functions, although some of his power is ceremonial. Susan is in love with Fate (a computer system) and prefers its cold, mathematical companionship to that of his fellow human beings. Susan also expresses a solipsist belief that he and God (referring to the Fate computer) are the only truly "real" beings in existence, though he also believes that he must devote his life to leading his people. He is an adherent of fascism and racist notions of "purity", and genuinely believes that civil liberties are dangerous and unnecessary. He appears to truly care for his people, however, and it is implied that his embrace of fascism was a response to his own loneliness. Before the War, he was a Chief Constable. He is assassinated by Rose Almond, the widow of one of his former lieutenants.

Eric Finch

Eric Finch is the chief of New Scotland Yard and Minister of Investigations, which has become known as the Nose. Finch is a pragmatist who sides with the government because he would rather serve in a world of order than one of chaos. He is nevertheless honourable and decent, and the Leader trusts him as reliable and lacking ambition. He eventually achieves his own anagnorisis and self-knowledge, expressing sorrow over his complicity with Norsefire's atrocities.

Supporting characters

- Derek Almond: A high-ranking official of the Norsefire government. He ran the government's secret police force, known as The Finger. Almond is warned by Finch that Surridge will be the last of V's targets and goes to her house to prevent him but is killed by V. Almond is replaced by Peter Creedy. His death sets in motion one of the novel's major story arcs; that of his widow, Rose, who is left penniless and traumatised by the loss of her husband, who was cold and abusive toward her but whom she nevertheless loved. In her grief and desperation, she blames her plight on Norsefire's leader, Adam Susan, and assassinates him at the novel's climax.

- Rosemary "Rose" Almond: The abused wife of Derek Almond. When her husband is murdered, Rose becomes depressed and must turn to Roger Dascombe (whom she strongly dislikes) for company and support. After Dascombe is also killed (also at the hands of V), she is forced to become a showgirl as a means of supporting herself. After V shuts down the surveillance systems, she uses the opportunity to buy a gun and assassinate Adam Susan. She is last shown in an interrogation conducted by the Finger and her fate is unknown. She is the only supporting character who at one point in the story drives the narrative through an inner monologue, which besides her is only done by V, Evey, Adam Susan and Finch.

- Peter Creedy: A coarse, petty man who replaces Derek Almond as the security minister of the Finger after the latter's death. He aims to replace the weakening Susan as Leader, but as part of Mrs. Heyer's plot, Alistair Harper's thugs kill him (Creedy had hired the thugs to bolster the weakening Finger, but Helen Heyer offered them more).

- Roger Dascombe: The technical supervisor for the Party's media division and the Propaganda Minister of The Mouth. In the first scene with him, he is presented as being openly effeminate. After Derek Almond's death, Dascombe sets his sights on his widow, Rosemary, who eventually turns to him for support. During V's attack on Jordan Tower, he is set up as a dummy V and killed by the police.

- Brian Etheridge: Head of The Ear. He is killed in the demolition of the Post Office Tower, which served as The Ear's headquarters.

- Alistair "Ally" Harper: The Scottish organised crime boss who kills Evey's lover Gordon. Initially Creedy hires him and his men to temporarily bolster the police force after V destroys the government's surveillance equipment, but Helen Heyer recruits him to her side to ensure Creedy's downfall by offering to place him in charge of the Finger after Conrad comes to power. He temporarily becomes Helen's lover. After Creedy's takeover, Ally fulfills his end of the bargain with Helen and kills Creedy with a lethal slash from his straight razor. Conrad beats Harper to death with a wrench as Ally fatally slices his neck.

- Gordon: A petty criminal specialising in bootlegging. After V abandons Evey during Book 2, Gordon takes her in as an act of kindness after he catches her stealing from his home and the two eventually become lovers. He is murdered by Alistair Harper, a ruthless gangster who is trying to expand Scotland's organised crime syndicate into London.

- Conrad Heyer: In charge of "The Eye" — the agency that controls the country's CCTV system. His wife Helen dominates him, and she intends for him to become leader, leaving her as the power behind the throne. V sends Conrad a videotape of Helen being unfaithful and he snaps, killing her lover Alistair Harper but sustaining a fatal wound from Harper's straight-edge razor in the process. When Helen learns what he has done, she is enraged at the destruction of her plans and leaves him to bleed to death, setting up a video camera connected to their TV so that he can watch himself die.

- Helen Heyer: The ruthless, scheming wife of Conrad Heyer. She uses sex and her superior intellect to keep her husband (for whom she feels nothing but contempt) in line, and to further her own goal of controlling the country after he becomes Leader. At the same time, she sleeps with Harper and turns him against Creedy. Her master plan collapses and she is last seen offering her body in exchange for protection and food to a semi-drunken gang after being rejected by Finch (who she hoped would join her in taking over what was left of the Party after her husband, Peter Creedy and Alistair Harper are all killed) and after anarchy has spilled into London.

- Bishop Anthony Lilliman: The voice of the Party in the Church. Lilliman is a corrupt priest who molests the young girls in his various parishes. Like Prothero, he worked at Larkhill before being given a higher employment by the state. Lilliman was a priest who was hired to give spiritual support to the prisoners being given Batch 5 drugs. He is killed after he almost rapes Evey Hammond (who is dressed up as a young girl), when V forces him to take communion with a cyanide-laced wafer.

- Valerie Page: A critically acclaimed actress who was imprisoned at Larkhill when the government found out she was a lesbian. Her tragic fate at the hands of the regime inspires V to fight against Norsefire.

- Lewis Prothero: The former Commander of Larkhill, the concentration camp that once held V. He later becomes The Voice of Fate, the government radio broadcaster who daily transmits "information" to the public. V stops a train carrying Prothero and kidnaps him. He is driven insane by a combination of an overdose of Batch 5 drugs and the shock of seeing his prized doll collection burned in a mock recreation of Camp Larkhill in V's headquarters. He remains incapacitated for the rest of the story.

- Dominic Stone: Inspector Finch's partner and protegé. Dominic is the one who figures out the connection between V and the former Larkhill camp staff and V's hacking into the Fate computer system. Very much like Finch, he only works as an officer in the Nose due to a sense of dedication to his country and not due to any political affiliation to the Norsefire Party. At the end, Evey rescues Dominic from a mob and takes him to the Shadow Gallery where it is implied she will train him as her successor after she has taken the persona of V.

- Dr. Delia Surridge: Larkhill camp doctor whom V kills by lethal injection of an unspecified drug. Surridge (the only one of V's former tormentors who feels remorse for her actions) apologises to him in her final moments of life. Finch also mentions that he has feelings for her, and he feels maddened at her death and determined to end V's life.

Themes and motifs

The series was Moore's first use of the densely detailed narrative and multiple plot lines that would feature heavily in Watchmen. Panel backgrounds are often crammed with clues and red herrings; literary allusions and wordplay are prominent in the chapter titles and in V's speech (which almost always takes the form of iambic pentameter, the line most commonly associated with William Shakespeare).

V reads Evey to sleep with The Magic Faraway Tree. This series provides the source of "The Land of Do-As-You-Please" and "The Land of Take-What-You-Want" alluded to throughout the series. Another cultural reference rings out – mainly in the theatrical version: "Remember, remember, the Fifth of November: the gunpowder treason and plot. I know of no reason why the gunpowder treason should ever be forgot". These lines allude directly to the story of Guy Fawkes and his participation in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Anarchism versus fascism

The two conflicting political viewpoints of anarchism and fascism dominate the story.[11] The Norsefire regime appears to share the fascist ideology of Hitler's National Socialist party: it is highly xenophobic, rules the nation through both fear and force, and worships strong leadership. In Moore's fictional fascist regime several different types of state organisations engage in power struggles with each other yet obey the same leader, again as was the case with Nazi Germany. V, meanwhile, ultimately strives for a "free society" ordered by its own consent using violence based revenge as his modus operandi.

Identity

V himself remains an enigma whose history is only hinted at. The bulk of the story is told from the viewpoints of other characters: V's admirer and apprentice Evey, a 16-year-old factory worker; Eric Finch, a world-weary and pragmatic policeman who is hunting V; and several contenders for power within the fascist party. As the story's central character V's destructive acts appear morally righteous given the fascistic system he rebels against. Thus a central theme of the series is the rationalization of atrocities in the name of a higher goal, whether it is stability or freedom.

Moore stated in an interview:

| “ | The central question is, is this guy right? Or is he mad? What do you, the reader, think about this? Which struck me as a properly anarchist solution. I didn't want to tell people what to think, I just wanted to tell people to think and consider some of these admittedly extreme little elements, which nevertheless do recur fairly regularly throughout human history.[12] | ” |

Moore has never clarified V's precise background, beyond stating, "that V isn't Evey's father, Whistler's Mother, or Charley's Aunt"; he does point out that V's identity is never revealed in the book. The ambiguity of the V character is a running theme through the work, which leaves readers to determine for themselves whether V is sane or psychotic, hero or villain. Before donning the Guy Fawkes mask herself, Evey comes to the conclusion that V's identity is unimportant compared to the role he plays, making his character itself the idea he embodies.

Adaptations

Film

The first filming of an adaptation of V for Vendetta for the screen involved one of the scenes in the documentary feature film The Mindscape of Alan Moore, shot in early 2002. The dramatisation contains no dialogue by the main character, but uses the Voice of Fate as an introduction.

On 17 March 2006 Warner Bros. released a feature-film adaptation of V for Vendetta, directed by James McTeigue (first assistant director on The Matrix films) from a screenplay by the Wachowskis. Natalie Portman stars as Evey Hammond and Hugo Weaving as V.

Alan Moore distanced himself from the film, as he has with every screen adaptation of his works to date. He ended co-operation with his publisher, DC Comics, after its corporate parent, Warner Bros., failed to retract statements about Moore's supposed endorsement of the movie.[13] After reading the script, Moore remarked:

| “ | [The movie] has been "turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country.... It's a thwarted and frustrated and largely impotent American liberal fantasy of someone with American liberal values standing up against a state run by neoconservatives – which is not what the comic V for Vendetta was about. It was about fascism, it was about anarchy, it was about England.[14] | ” |

He later adds that if the Wachowskis had wanted to protest about what was going on in the United States, then they should have used a political narrative that directly addressed the issues of the USA, similar to what Moore had done before with Britain. The film arguably changes the original message by having removed any reference to actual Anarchism in the revolutionary actions of V. An interview with producer Joel Silver reveals that he identifies the V of the comics as a clear-cut "superhero... a masked avenger who pretty much saves the world," a simplification that goes against Moore's own statements about V's role in the story.[15]

Co-author and illustrator David Lloyd, by contrast, embraced the adaptation.[16] In an interview with Newsarama he states:

| “ | It's a terrific film. The most extraordinary thing about it for me was seeing scenes that I'd worked on and crafted for maximum effect in the book translated to film with the same degree of care and effect. The "transformation" scene between Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving is just great. If you happen to be one of those people who admires the original so much that changes to it will automatically turn you off, then you may dislike the film—but if you enjoyed the original and can accept an adaptation that is different to its source material but equally as powerful, then you'll be as impressed as I was with it.[17] | ” |

Steve Moore (no relation to Alan Moore) wrote a novelisation of the film's screenplay, published in 2006.

Cultural impact

Anonymous, an Internet-based group, has adopted the Guy Fawkes mask as their symbol (in reference to an Internet meme). Members wore such masks, for example, during Project Chanology's protests against the Church of Scientology in 2008. Alan Moore had this to say about the use of the Guy Fawkes motif adopted from his comic V for Vendetta, in an interview with Entertainment Weekly:

| “ | I was also quite heartened the other day when watching the news to see that there were demonstrations outside the Scientology headquarters over here, and that they suddenly flashed to a clip showing all these demonstrators wearing V for Vendetta Guy Fawkes masks. That pleased me. That gave me a warm little glow.[18] | ” |

_by_anonymous.tif.jpg)

According to Time, the protesters' adoption of the mask has led to it becoming the top-selling mask on Amazon.com, selling hundreds of thousands a year.[19]

The film allegedly inspired some of the Egyptian youth before and during the 2011 Egyptian revolution.[20][21][22][23]

On 23 May 2009 protesters dressed up as V and set off a fake barrel of gunpowder outside Parliament while protesting over the issue of British MPs' expenses.[24]

During the Occupy Wall Street and other ongoing Occupy protests, the mask appeared internationally[25] as a symbol of popular revolution. Artist David Lloyd stated: "The Guy Fawkes mask has now become a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny – and I'm happy with people using it, it seems quite unique, an icon of popular culture being used this way."[26]

On 17 November 2012 police officials in Dubai warned against wearing Guy Fawkes masks painted with the colours of the UAE flag during any celebration associated with the UAE National Day (2 December), declaring such use an illegal act after masks went on sale in online shops for 50 DHS.[27]

The Humanity Party, a registered political party in the United States, is represented by "Anonymous." It also uses the Guy Fawkes mask. This has led some to criticize the Humanity Party for its possible connection to "hackers": "[H]acktivists are asking US voters to write the word 'Anonymous' in the write-in space on their ballots."[28]

Others criticize the party for being associated with the "New World Order," disapproved by some conservatives and conspiracy theorists.[28]

Others found the party's message to be sufficiently noteworthy that they posted the official video for the party on their website. One posting garnered half a million views and over 7,000 comments.

One news media outlet wrote:

| “ | "The Vote Anonymous 2016 initiative is being backed by a brand new political party calling themselves 'The Humanity Party.' The Humanity Party just like any other political party, has written its own preamble, as well as a complete party platform to let us all know exactly what it is that they stand for and against. The newly formed Humanity Party claims that they officially register themselves as an official American Political party so long as they receive a majority of the vote in the upcoming Presidential elections. At which point they will begin calling for the complete restructuring of the United States Government to actually be made up of, by, and for the people; eliminate State’s rights; create a new modernized U.S. Constitution; Create new laws that are the same for all citizens; drastically reduce the power and size of local police forces; apologize to all other foreign nations for the United States reign of terror and bullying on a global scale and several other equally important and vital issues plaguing the American people."[29] | ” |

Collected editions

The entire story has appeared collected in paperback (ISBN 0-930289-52-8) and hardback (ISBN 1-4012-0792-8) form. In August 2009 DC published a slipcased Absolute Edition (ISBN 1-4012-2361-3); this includes newly coloured "silent art" pages (full-page panels containing no dialogue) from the series' original run, which have not appeared in any previous collected edition.[30]

References

- ↑ Harvey, Allan (June 2009). "Blood and Sapphires: The Rise and Demise of Marvelman". Back Issue!. TwoMorrows Publishing (34): 71.

- 1 2 3 Moore, Alan (1983). "Behind the Painted Smile". Warrior (17).

- ↑ Brown, Adrian (2004). "Headspace: Inside The Mindscape Of Alan Moore" (http). Ninth Art. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "David Lloyd Comic Artist 09: Night Raven inspiration for V...," VideoSurf. Accessed 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Keller, James R. (2008). V for vendetta as cultural pastiche. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3467-1.

- ↑ Galdon Rodriguez, Angel (2011). George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four as an Influence on Popular Culture Works: V for Vendetta and 2024. Albacete: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

- ↑ Boudreaux, Madelyn (1994). "Introduction". An Annotation of Literary, Historic and Artistic References in Alan Moore's Graphic Novel, "V for Vendetta". Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Moore, Alan, Introduction. V for Vendetta. New York: DC Comics, 1990.

- ↑ The Comics Journal No. 210, February 1999, page 44

- ↑ Moore, Alan (w), Lloyd, David (p). "V for Vendetta" V for Vendetta v10,: 28/6 (May 1989), DC Comics

- ↑ "Authors on Anarchism — an Interview with Alan Moore". Strangers in a Tangled Wilderness. Infoshop.org. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ MacDonald, Heidi (2006). "A for Alan, Pt. 1: The Alan Moore interview". The Beat. Archived from the original on 4 April 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "Moore Slams V for Vendetta Movie, Pulls LoEG from DC Comics". comicbookresources.com. Comic Book Resources. 22 April 2006.

- ↑ MTV (2006). "Alan Moore: The last angry man". MTV.com. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Douglas, Edward (2006). "V for Vendetta's Silver Lining". Comingsoon.net. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "V at Comic Con". Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "David Lloyd: A Conversation". Newsarama. Archived from the original on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-14.

- ↑ Gopalan, Nisha (21 July 2008). "Alan Moore Still Knows the Score!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ Carbone, Nick (29 August 2011). "How Time Warner Profits from the 'Anonymous' Hackers". Time. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ "V for Vendetta": The Other Face of Egypt's Youth Movement, Jadaliyya

- ↑ اليوم السابع | V» for Egypt». Youm7.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-12.

- ↑ ريفيو فيلم: V for Vendetta :: مجلة مِصّرِي :: حين قامت ثوره 25 يناير السنة الماضية ساند مسيرة الثوره الكثير من الفنانين من مختلف الميادين، واسترجع الشباب اشعار نجم واغانى إمام. Myegyptmag.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-12.

- ↑ V for Vendetta masks: From a 1980s comic book to the Egyptian revolution – Stage & Street – Arts & Culture – Ahram Online. English.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved on 2013-08-12.

- ↑ "BBC.com news report, Saturday, 23 May 2009 16:49 UK". BBC News. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ↑ "V for vague: Occupy Sydney's faceless leaders". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Waites, Rosie (20 October 2011). "V for Vendetta masks: Who". BBC News. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ↑ Barakat, Noorhan (17 November 2012). "Vendetta masks in UAE colours draw warning". Gulf News. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- 1 2 Balotsky, Denis (7 April 2016). "Celebrity X". Sputnik News. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- ↑ Pinkman, Walter (29 March 2016). "Are You Sick And Tired Of Voting For The Lesser Of Two Evils?". American News X.

- ↑ "Absolute V For Vendetta" to feature 100 additional pages at no extra cost Comicbookresources.com. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: V for Vendetta |

- V for Vendetta – The Ultimate Collection Website official collection site

- V for Vendetta official site at DC Comics

- V for Vendetta: Comic vs. Film at IGN

- An Annotation of Literary, Historic and Artistic References in Alan Moore's Graphic Novel, V For Vendetta by Madelyn Boudreaux

- Interview with the British man who designed the Anonymous (V for Vendetta) mask, what he thinks of how it’s being used by PostDesk