Ethnic groups in Burundi

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Burundi |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

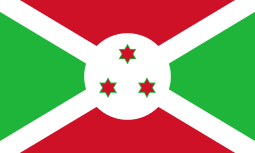

Symbols |

|

The indigenous population of Burundi belongs to three major ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa.[lower-alpha 1] Its ethnic make-up is similar to that of Rwanda.[1] Other groups from elsewhere in Africa, Europe, and Asia are also represented as a result of recent immigration.

Indigenous population

Ethnic groups

Native Burundians belong to one of the three major ethnic groups in Burundi: the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa peoples. The historical origins of ethnic differentiation between Hutu and Tutsi are disputed, however members of both groups consider themselves distinct.[2][3]

The Hutu are the largest ethnic group in Burundi, representing approximately 80 percent of Burundians.[2] Historically, they lived as agriculturalists. Under Burundi's Tutsi-dominated postcolonial government between 1965 and 2001, the Hutu population was marginalised and subordinated to the Tutsi elites.[2] The first Hutu to become head of state was Melchior Ndadaye in 1993, although he was assassinated shortly after taking power.[4] Since the end of the Burundian Civil War (1993–2005), Hutus have been dominant in political life.[2]

Tutsi represent approximately 19 percent of the national population.[2] Historically, the Tutsi dominated political institutions in Burundi, including the nation's monarchy. They lived as pastoralists. Even after the abolition of the monarchy in 1966, the subsequent dictatorial regimes of Michel Micombero (1966–76), Jean-Baptiste Bagaza (1976–87), and Pierre Buyoya (1987–93) were dominated by Tutsi elites which often consciously discriminated against the Hutu majority.[5]

The Twa are the smallest indigenous ethnic group in Burundi and are a pygmy people. There are estimated to be between 30–40,000 Twa living in Burundi (one percent of the national population).[6] As an ethnic group, they have links to the pygmy peoples of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They traditionally lived as hunter-gatherers and musicians but, following bans on hunting and land re-distribution, now often work as unskilled labourers.[7][6] The Batwa have been economically and politically marginalised by the other two ethnic groups.[7] They are often disproportionately poor and suffer from legal discrimination.[6]

Ethnic tensions and violence

Since Burundi became independent from Belgian colonial rule in 1962, it has seen extensive violence between members of the Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups.[8] Ethnic violence peaked in 1972 when 100,000 people, mainly Hutu, were killed by the Tutsi regime in the Burundian Genocide.[2] Twa have also been targeted, specifically in violence directed against the Tutsi with whom they are sometimes associated.[6] Ethnic violence has often been attributed to the agitation of political factions attempting to consolidate their power, as well as to competition for resources.[1] Burundi's ethnic tensions have been compared to those in Rwanda which saw similar ethnic tension between Hutu and Tutsi flare up into violence on several occasions, notably during the Rwandan Genocide.[8]

As a measure to limit the possibilities for discrimination, the 2005 Burundian constitution prescribes ethnic quotas (usually 60 percent Hutu to 40 percent Tutsi) in certain government institutions, including the military.[9] Three seats in each house of the Burundian government are allocated to the Twa.[6]

Immigrant ethnic groups

A significant number of recent immigrants live in Burundi. Most come from neighbouring Central African countries (especially the Congo, Tanzania, and Rwanda) but other come from West Africa. There is also a European and Asian community in the country.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ In most Bantu languages, the prefix ba- (or wa-) is added to a human noun to form a plural. As such, Bahutu would refer collectively to members of the Hutu ethnic group, Batutsi to Tutsi, and Batwa to the Twa.

Footnotes

- 1 2 Uvin 1999, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jones, Cara E. (15 December 2015). "There are signs of renewed ethnic violence in Burundi". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Uvin 1999, p. 254.

- ↑ Uvin 1999, p. 262.

- ↑ Ndura, Elavie (2015). "Ethnic Relations and Burundi's Struggle for Sustainable Peace" (PDF). United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Twa". World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. Minority Rights Group International. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 "An indigenous community in Burundi battles for equal treatment". Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (United Nations). Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Burundian time-bomb". The Economist. 23 April 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ "Twa people in Burundi: "We want to be fully integrated in institutions"". IWACU English News. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Grira, Safwene (1 March 2016). "Plongé dans une crise sécuritaire, le Burundi recense ses étrangers". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Uvin, Peter (1999). "Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence". Comparative Politics. 31 (3): 253–71. JSTOR 422339.