Single-use zoning

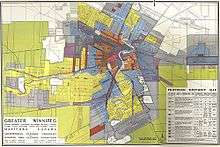

Single-use zoning, also known as Euclidean zoning, is a tool of urban planning that controls land uses in a city. The earliest forms of single-use zoning were practiced in New York city in the early 1900's to guide its rapid population growth from immigration.[1] Land uses were divided into residential, commercial and industrial areas, now referred to as zones or zoning districts in cities. Single-use zoning became known as Euclidean zoning because of a court case in Euclid, Ohio that established its constitutionality, Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

Euclidean zoning has been the dominant system of zoning in much of North America since its first implementation.[2] The predictable model for dividing land use patterns generated by the Euclidean system have been charged by many commentators as playing a direct role in a number of problems in land use planning evident in the United States and elsewhere. Single-use zoning is a basic model that has not evolved to create appropriate solutions for the increasing complexity of social, political and environmental challenges in cities.[1]

Problems affiliated with Euclidean-style zoning policy include suburban sprawl, urban decay, environmental pollution, racial and socioeconomic segregation, negative economic impacts and an overall reduced quality of life.[3][4] Land use regulations associated with a high separation of land uses have also been criticized as being fraught with legal obstacles to rehabilitating neighbourhoods affected by the aforementioned problems [3] (such efforts are often referred to as urban rehabilitation or urban renewal).

Euclidean zoning represents a functionalist way of thinking that uses mechanistic principles to conceive of the city as a fixed machine. This conception is in opposition to the view of the city as a continually evolving organism or living system, as first espoused by the German urbanist Hans Reichow.

Criticisms

Planning and community activist Jane Jacobs wrote extensively on the connections between Euclidean zoning and the destruction and displacement of communities in New York City. Her work details how conventional zoning often leads to the decay of municipal infrastructure and social capital and perpetuates brutal cycles of poverty and chronic under-funding in certain neighbourhoods.[5] Jacob's writings, along with increasing public dissatisfaction with the attendant problems of urban sprawl, is often credited with inspiring the New Urbanism movement and the ensuing body of literature concerned with solutions to uneven city development.

Critics argue that putting everyday uses out of walking distance of each other leads to an increase in traffic since people have to get in their cars and drive to meet their needs throughout the day. Single zoning and urban sprawl have also been criticized as making work–family balance more difficult to achieve, as greater distances need to be covered in order to integrate the different life domains.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 Elliot, Donald (2012). A Better Way to Zone : Ten Principles to Create More Livable Cities. Island Press.

- ↑ in 1916 New York became the first became the first city of implement this type of zoning law, later upheld in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926). “Operating from the premise that everything has its place, [Euclidean] zoning is the comprehensive division of a city into different use zones.” JULIAN CONRAD JUERGENSMEYER & THOMAS E. ROBERTS, LAND USE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT REGULATION LAW § 4.2, at 80 (1998) (cited in BLACK’S LAW DICTIONARY under Euclidean zoning.

- 1 2 Hall, E. (2006). Divide and sprawl, decline and fall: A comparative critique of Euclidean zoning. U. Pitt. L. Rev., 68, 915.

- ↑ Jay Wickersham, Jane Jacob’s Critique of Zoning: From Euclid to Portland and Beyond, 28 B.C. ENVTL. AFF. L. REV. 547, 557 (2001).

- ↑ Jacobs, Jane. The Life and Death of Great American Cities. Vintage.

- ↑ Katharine Baird Silbaugh: Women's Place: Urban Planning, Housing Design, and Work-Family Balance, Fordham Law Review, Vol. 76, 2008 Boston Univ. School of Law Working Paper No. 07-12. Downloaded on January 15, 2012, from: Social Science Research Network (abstract, fulltext), see page 1825