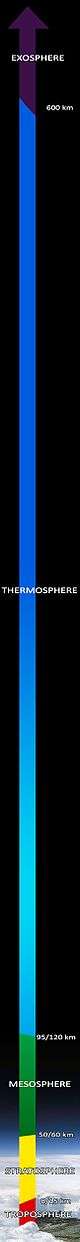

Exosphere

The exosphere (Ancient Greek: ἔξω éxō "outside, external, beyond", Ancient Greek: σφαῖρα sphaĩra "sphere") is a thin, atmosphere-like volume surrounding a planet or natural satellite where molecules are gravitationally bound to that body, but where the density is too low for them to behave as a gas by colliding with each other.[1] In the case of bodies with substantial atmospheres, such as Earth's atmosphere, the exosphere is the uppermost layer, where the atmosphere thins out and merges with interplanetary space. It is located directly above the thermosphere.

Several moons, such as the Moon and the Galilean satellites of Jupiter, have exospheres without a denser atmosphere underneath,[2] referred to as a surface boundary exosphere.[3] Here, molecules are ejected on elliptic trajectories until they collide with the surface. Smaller bodies such as asteroids, in which the molecules emitted from the surface escape to space, are not considered to have exospheres.

Earth's exosphere

The most common molecules within Earth's exosphere are those of the lightest atmospheric gasses. Hydrogen is present throughout the exosphere, with some helium, carbon dioxide, and atomic oxygen near its base. Because it can be difficult to define the boundary between the exosphere and outer space (see "Upper boundary" at the end of this section), the exosphere may be considered a part of interplanetary or outer space.

Lower boundary

The lower boundary of the exosphere is called the exobase. It is also called exopause and 'critical altitude' as this is the altitude where barometric conditions no longer apply. Atmospheric temperature becomes nearly a constant above this altitude.[4] On Earth, the altitude of the exobase ranges from about 500 to 1,000 kilometres (310 to 620 mi) depending on solar activity.[5]

The exobase can be defined in one of two ways:

If we define the exobase as the height at which upward-traveling molecules experience one collision on average, then at this position the mean free path of a molecule is equal to one pressure scale height. This is shown in the following. Consider a volume of air, with horizontal area and height equal to the mean free path , at pressure and temperature . For an ideal gas, the number of molecules contained in it is:

where is the universal gas constant. From the requirement that each molecule traveling upward undergoes on average one collision, the pressure is:

where is the mean molecular mass of the gas. Solving these two equations gives:

which is the equation for the pressure scale height. As the pressure scale height is almost equal to the density scale height of the primary constituent, and because the Knudsen number is the ratio of mean free path and typical density fluctuation scale, this means that the exobase lies in the region where.

The fluctuation in the height of the exobase is important because this provides atmospheric drag on satellites, eventually causing them to fall from orbit if no action is taken to maintain the orbit.

Upper boundary of Earth

In principle, the exosphere covers distances where particles are still gravitationally bound to Earth, i.e. particles still have ballistic orbits that will take them back towards Earth. The upper boundary of the exosphere can be defined as the distance at which the influence of solar radiation pressure on atomic hydrogen exceeds that of Earth's gravitational pull. This happens at half the distance to the Moon (the average distance between Earth and the Moon is 384,400 kilometres (238,900 mi)). The exosphere, observable from space as the geocorona, is seen to extend to at least 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi) from Earth's surface. The exosphere is a transitional zone between Earth's atmosphere and space.

Moon's exosphere

On 17 August 2015, based on studies with the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) spacecraft, NASA scientists reported the detection of neon in the exosphere of the moon.[1]

References

- 1 2 Steigerwald, William (17 August 2015). "NASA's LADEE Spacecraft Finds Neon in Lunar Atmosphere". NASA. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ Day, Brian (20 August 2013). "Why LADEE Matters". NASA Ames Research Center. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ "Is There an Atmosphere on the Moon?". NASA. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Bauer, Siegfried; Lammer, Helmut. Planetary Aeronomy: Atmosphere Environments in Planetary Systems, Springer Publishing, 2004.

- ↑ "Exosphere - overview". UCAR. 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

External links

- Gerd W. Prolss: Physics of the Earth's Space Environment: An Introduction. ISBN 3-540-21426-7