2022 FIFA World Cup

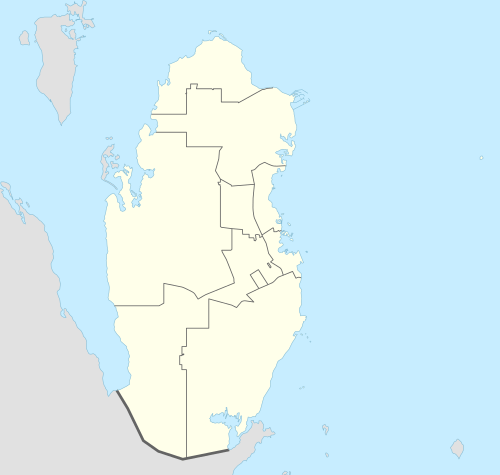

| كأس العالم لكرة القدم 2022 Qatar 2022 | |

|---|---|

|

Bid logo | |

| Tournament details | |

| Host country | Qatar |

| Dates | 21 November – 18 December 2022 (28 days) |

| Teams | 32 (from 5 or 6 confederations) |

| Venue(s) | 8 or 12 (in 7 municipalities) |

The 2022 FIFA World Cup is scheduled to be the 22nd edition of the FIFA World Cup, the quadrennial international men's football championship contested by the national teams of the member associations of FIFA. It is scheduled to take place in Qatar in 2022. This will be the first time the World Cup will be held in the Middle East, and in an Arab and a Muslim country. Provided the current format is not changed for this tournament, it will involve 32 national teams, including the host nation.

This will also mark the first World Cup not to be held in June or July; the tournament is instead scheduled for late November till mid-December. It is to be played in a reduced timeframe of around 28 days, with the final being held on 18 December 2022, which is also Qatar National Day.[1]

Accusations of corruption have been made relating to how Qatar won the right to host the event. FIFA completed an internal investigation into these allegations and a report cleared Qatar of any wrongdoing, but the chief investigator Michael Garcia has since described FIFA's report on his inquiry as "materially incomplete and erroneous".[2] On 27 May 2015, Swiss federal prosecutors opened an investigation into corruption and money laundering related to the awarding of the 2018 and 2022 World Cups.[3][4]

On 7 June 2015, it was announced that Qatar would possibly no longer be eligible to host the event, if evidence of bribery was proven. According to Domenico Scala, the head of FIFA's Audit And Compliance Committee: "Should there be evidence that the awards to Qatar and Russia came only because of bought votes, then the awards could be cancelled".[5][6]

Qatar has faced strong criticism due to the treatment of foreign workers involved in preparation for the World Cup, with Amnesty International referring to "forced labour" and stating that workers have been suffering human rights abuses, despite worker welfare standards being drafted in 2014.[7]

Host selection

| Wikinews has related news: FIFA announce Russia to host 2018 World Cup, Qatar to host 2022 World Cup |

The bidding procedure to host the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups began in January 2009, and national associations had until 2 February 2009 to register their interest.[8] Initially, eleven bids were made for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, but Mexico later withdrew from proceedings,[9][10] and Indonesia's bid was rejected by FIFA in February 2010 after the Indonesian Football Association failed to submit a letter of Indonesian government guarantee to support the bid.[11] Indonesian officials had not ruled out a bid for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, until Qatar took the 2022 cup. During the bidding process, all non-UEFA nations gradually withdrew from the 2022 bids for the 2018 one, thus making the UEFA nations ineligible for the bid.

In the end, there were five bids for the 2022 FIFA World Cup: Australia, Japan, Qatar, South Korea and the United States. The twenty-two member FIFA Executive Committee convened in Zürich on 2 December 2010 to vote to select the hosts of both tournaments.[12] Two FIFA executive committee members were suspended before the vote in relation to allegations of corruption regarding their votes.[13] The decision to host the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, which was graded as having "high operational risk",[14] generated criticism from media commentators, American, Australian, and British officials.[15] It has been criticised as many to be part of the FIFA corruption scandals.[16]

The voting patterns were as follows:[17]

| Bidders | Votes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 | |

| 11 | 10 | 11 | 14 | |

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | — | |

| 3 | 2 | — | — | |

| 1 | — | — | — | |

There have been allegations of bribery and corruption in the selection process involving members of FIFA's executive committee. These allegations are being investigated by FIFA. (See § Bidding corruption allegations, below.)

Qatar is the smallest nation by area ever to have been awarded a FIFA World Cup – the next smallest by area is Switzerland, host of the 1954 FIFA World Cup, which is more than three times as large as Qatar and only needed to host 16 teams instead of the current 32. On current population, Qatar would be the smallest host country by population – Uruguay had a population of 1.9 million when it hosted the 1930 World Cup,[18] more than Qatar's 2013 population of 1.7 million.[19] However, the Qatar Statistical Authority predicts that the total population of Qatar could reach 2.8 million by 2020.

Qualification

The qualification process for the 2022 World Cup has not yet been announced. All FIFA member associations, of which there are currently 211, are eligible to enter qualification. Qatar, as hosts, qualified automatically for the tournament.

The allocation of slots for each confederation was discussed by the FIFA Executive Committee on 30 May 2015 in Zürich after the FIFA Congress.[20] It was decided that the same allocation as 2014 would be kept for the 2018 and 2022 tournaments.[21]

Qualified teams

| Team | Order of qualification |

Method of qualification |

Date of qualification |

Finals appearance |

Last appearance |

Previous best performance |

FIFA Ranking at start of event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Host | 2 December 2010 | 1st |

- ^A Qatar may still qualify for the 2018 FIFA World Cup. If they do, they will appear in the World Cup for the first time in 2018 and for the second time in 2022. Otherwise, they will make their debut appearance in 2022.

Venues

The first five proposed venues for the World Cup were unveiled at the beginning of March 2010. The stadiums aim to employ cooling technology capable of reducing temperatures within the stadium by up to 20 °C (36 °F), and the upper tiers of the stadiums will be disassembled after the World Cup and donated to countries with less developed sports infrastructure.[22] All of the five stadium projects launched have been designed by German architect Albert Speer & Partners.[23] Leading football clubs in Europe wanted the World Cup to take place from 28 April to 29 May rather than the typical June and July staging, due to concerns about the heat.[24]

A report released on 9 December 2010 quoted FIFA President Sepp Blatter as stating that other nations could host some matches during the World Cup. However, no specific countries were named in the report.[25] Blatter added that any such decision must be taken by Qatar first and then endorsed by FIFA's executive committee.[26] Prince Ali bin Al Hussein of Jordan told the Australian Associated Press that holding games in Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, and possibly Saudi Arabia would help to incorporate the people of the region during the tournament.[27]

According to a report released in April 2013 by Merrill Lynch, the investment banking division of Bank of America, the organizers in Qatar have requested FIFA to approve a smaller number of stadiums due to the growing costs.[28] Bloomberg.com said that Qatar wishes to cut the number of venues to 8 or 9 from the 12 originally planned.[29]

| Lusail | Doha | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lusail Iconic Stadium | Khalifa International Stadium | Sports City Stadium | Education City Stadium |

| Capacity: 86,250 (planned) |

Capacity: 40,000 (plans to expand to 68,030) |

Capacity: 47,560 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,350 (planned) |

| Al Khor | Madinat ash Shamal | ||

| Al-Khor Stadium | Al-Shamal Stadium | ||

| Capacity: 45,330 (planned) |

Capacity: 45,120 (planned) | ||

| Al Wakrah | Umm Salal | ||

| Al-Wakrah Stadium | Umm Salal Stadium | ||

| Capacity: 45,120 (Under construction) |

Capacity: 45,120 (planned) | ||

| Doha | Al Rayyan | ||

| Doha Port Stadium | Thani bin Jassim Stadium | Qatar University Stadium | Ahmed bin Ali Stadium |

|

| ||

| Capacity: 44,950 (planned) |

Capacity: 21,282 (plans to expand to 44,740) |

Capacity: 43,520 (planned) |

Capacity: 21,282 (plans to expand to 44,740) |

Controversies

A number of groups and media outlets have expressed concern over the suitability of Qatar to host the event,[30][31] with regard to interpretations of human rights, particularly worker conditions, the rights of fans in the LGBT community,[31][32][33][34] climatic conditions and accusations of Qatar for supporting terrorism both diplomatically and financially.[35]

The selection of Qatar as the host country has been controversial; FIFA officials were accused of corruption and allowing Qatar to "buy" the World Cup,[36] the treatment of construction workers was called into question by human rights groups,[37] and the high costs needed to make the plans reality were criticised. The climate conditions caused some to call hosting the tournament in Qatar infeasible, with initial plans for air-conditioned stadiums giving way to a potential date switch from summer to winter. Sepp Blatter, who was FIFA President when Qatar was selected, later remarked that awarding the World Cup to Qatar was a "mistake" because of the extreme heat.[38][39]

Workers' conditions

The issue of migrant workers' rights has also attracted attention, with an investigation by The Guardian newspaper claiming that many workers are denied food and water, have their identity papers taken away from them, and that they are not paid on time or at all, making some of them in effect slaves. The Guardian has estimated that up to 4,000 workers may die due to lax safety and other causes by the time the competition is held.[37] These claims are based upon the fact that 522 Nepalese[40] workers and over 700 Indian[41] workers have died since 2010, when Qatar's bid as World Cup's host was won. That's about 250 Indian workers dying each year.[42] Given that there are half a million Indian workers in Qatar, the Indian government says that is quite a normal number of deaths.[42] In the United Kingdom, in any group of half a million 25–30-year-old men, an average of 300 die each year, a higher rate than among Indian workers in Qatar.[42]

In 2015, a crew of 4 journalists from the BBC were arrested and held for two days after they attempted to report on the condition of workers in the country.[43] The reporters had been invited to visit the country as guests of the Qatari government.[43]

The Wall Street Journal reported in June 2015 the International Trade Union Confederation's claim that over 1,200 workers had died while working on infrastructure and real-estate projects related to the World Cup, and the Qatar government's counter-claim that no-one had.[44] The BBC later reported that this often-cited figure of 1,200 workers having died in World Cup construction in Qatar between 2011 and 2013, is not correct, and that the 1,200 number is instead representing deaths from all Indians and Nepalese working in Qatar, not just of those workers involved in the preparation for the World Cup, and not just of construction workers.[42] Most Qatar nationals avoid doing manual work or low skilled jobs; additionally, they are given preference at the workplace.[45][46]

Move to November and December

Sports Illustrated reported on 18 February 2015 that the event will be staged from mid-November to mid-December.[47] Owing to the climate in Qatar, concerns have been expressed since the bid was made about holding the event during the traditional months for the World Cup finals of June and July. In October 2013, a task force was commissioned to consider alternative dates and report after the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.[48] On 24 February 2015, the FIFA Task Force proposed that the tournament be played from late November to late December 2022,[49] to avoid the summer heat between May and September and also avoid clashing with the 2022 Winter Olympics in February and Ramadan in April.[50]

The notion of staging the tournament in November is controversial since it would interfere with the regular season schedules of domestic leagues around the world. Commentators have noted the clash with the Western Christmas season is likely to cause disruption, whilst there is concern about how short the tournament is intended to be.[51] It would also force the postponement of the 2023 Africa Cup of Nations from January to June to prevent African players from having a quick turnaround. FIFA executive committee member Theo Zwanziger said that awarding the 2022 World Cup to Qatar's desert state was a "blatant mistake".[52] Frank Lowy, chairman of Football Federation Australia, said that if the 2022 World Cup were moved to November and thus upset the schedule of the A-League, they would seek compensation from FIFA.[53] Richard Scudamore, chief executive of the Premier League, stated that they would consider legal action against FIFA because a move would interfere with the Premier League's popular Christmas and New Year fixture programme.[54] On 19 March 2015, FIFA sources confirmed that the 2022 World Cup final would be played on Sunday 18 December.[55]

Bidding corruption allegations

.jpg)

Qatar has faced growing pressure over its hosting of the World Cup in relation to allegations over the role of former top football official Mohammed bin Hammam played in securing the bid.[56]

A former employee of the Qatar bid team alleged that several African officials were paid $1.5m by Qatar.[57] She retracted her claims, but later said she was coerced to do so by Qatari bid officials.[58][59] More suspicions emerged in March 2014 when it was discovered that disgraced former CONCACAF president Jack Warner and his family were paid almost $2 million from a firm linked to Qatar's successful campaign. The FBI is investigating Warner and his alleged links to the Qatari bid.[60]

Five of FIFA's six primary sponsors, Sony, Adidas, Visa, Hyundai and Coca-Cola, have called upon FIFA to investigate the claims.[61][62] The Sunday Times published bribery allegations based on a leak of millions of secret documents.[63] FIFA vice-president Jim Boyce has gone on record stating he would support a re-vote to find a new host if the corruption allegations are proven.[64][65] FIFA completed a lengthy investigation into these allegations and a report cleared Qatar of any wrongdoing.

Despite the claims, the Qataris insist that the corruption allegations are being driven by envy and mistrust while Sepp Blatter said it is fueled by racism in the British media.[66][67]

In the 2015 FIFA corruption case, Swiss officials, operating under information from the United States Department of Justice, arrested many senior FIFA officials in Zurich, Switzerland. They also seized physical and electronic records from FIFA's main headquarters. The arrests continued in the United States where several FIFA officers were arrested and FIFA buildings raided. The arrests were made on the information of at least a $150 million (USD) corruption and bribery scandal.[68]

On 7 June 2015, Phaedra Almajid, the former media officer for the Qatar bid team claimed that the allegations would result in Qatar not hosting the World Cup.[69] In an interview published on the same day, Domenico Scala, the head of FIFA's Audit And Compliance Committee, stated that "should there be evidence that the awards to Qatar and Russia came only because of bought votes, then the awards could be cancelled".[5][6]

Broadcasting rights

-

Australia – SBS[70]

Australia – SBS[70] -

Brazil – Rede Globo, SporTV[71]

Brazil – Rede Globo, SporTV[71] -

Canada – CTV, TSN, RDS[72]

Canada – CTV, TSN, RDS[72] - Caribbean – International Media Content, SportsMax[73]

-

India – Sony SIX

India – Sony SIX -

Europe – European Broadcasting Union (37 countries)[74]

Europe – European Broadcasting Union (37 countries)[74] -

Germany – ARD, ZDF[75]

Germany – ARD, ZDF[75] -

Portugal – RTP[76]

Portugal – RTP[76] -

United Kingdom - BBC, ITV

United Kingdom - BBC, ITV - Middle East – beIN Sports

-

United States – Fox, Telemundo[77]

United States – Fox, Telemundo[77]

See also

References

- ↑ "FIFA Executive Committee confirms November/December event period for Qatar 2022". FIFA.com. 19 March 2015.

- ↑ "Fifa report 'erroneous', says lawyer who investigated corruption claims". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Criminal investigation into 2018 and 2022 World Cup awards opened". ESPN FC. ESPN. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland seizes documents at FIFA". The Federal Council. The Swiss Government. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- 1 2 "'Russia & Qatar may lose World Cups' – Fifa official". BBC News. 7 June 2015.

- 1 2 Owen Gibson (7 June 2015). "Russia and Qatar may lose World Cups if evidence of bribery is found". The Guardian.

- ↑ http://www.eurosport.com/football/amnesty-says-workers-at-qatar-world-cup-stadium-suffer-abuse_sto5416371/story.shtml

- ↑ Goff, Steve (16 January 2009). "Future World Cups". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ↑ "2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup bids begin in January 2009". Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ↑ "World Cup 2018". 5 January 2015.

- ↑ "Indonesia's bid to host the 2022 World Cup bid ends". BBC Sport. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 March 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Combined bidding confirmed". FIFA. 20 December 2008. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ↑ Wilson, Steve (18 November 2010). "World Cup 2018: meet Amos Adamu and Reynald Temarii, the Fifa pair suspended over corruption". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ "World Cup 2022: Blow to Qatar's 2022 bid as FIFA brands it "high risk"". Bloomberg. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ James, Stuart (2 December 2010). "World Cup 2022: 'Political craziness' favours Qatar's winning bid". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ↑ "Qatar world cup part of FIFA corruption scandal". 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Doyle, Paul; Busfield, Steve (2 December 2010). "World Cup 2018 and 2022 decision day – live!". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ URUGUAY: historical demographic data of the whole country. Populstat Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ "Population structure". Qatar Statistics Authority. 31 January 2013.

- ↑ "2022 FIFA World Cup to be played in November/December". FIFA.com. 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "Current allocation of FIFA World Cup™ confederation slots maintained". FIFA.com. 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "Bidding Nation Qatar 2022 – Stadiums". Qatar2022bid.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ↑ "2022 FIFA World Cup Bid Evaluation Report: Qatar" (PDF). FIFA. 5 December 2010.

- ↑ Richard Conway (30 October 2014). "World Cup 2022: European clubs want spring finals in Qatar". BBC Sports. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ "Report: Qatar neighbors could host 2022 WC games". Fox Soccer/AP. 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "FIFA 'backs' winter 2022 Qatar cup – FOOTBALL". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ "Jordan's Prince Ali calls for winter WCup in Qatar". Yahoo! Sports/AP. 13 December 2010.

- ↑ "Qatar 2022: Nine stadiums instead of twelve? –". Stadiumdb.com. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Fattah, Zainab (22 April 2013). "Qatar Is in Talks to Reduce World Cup Stadiums, BofA Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Kaufman, Michelle. "Tiny Qatar beats out America for World Cup – Total Soccer | Fútbol Total". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- 1 2 James, Stuart (2 December 2010). "World Cup 2022: 'Political craziness' favours Qatar's winning bid". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Geen, Jessica. "Gay groups' anger at 'homophobic' World Cup hosts Russia and Qatar". Pink News. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "Qatar's World Cup won't be gay-friendly". news.com.au. 3 December 2010.

- ↑ "Still Slaving Away." The Economist. 6 June 2015: 38-39. Print.

- ↑ Samuel, Martin (18 March 2014). "New Qatar controversy as World Cup hosts are linked to terrorism". dailymail.co.uk. London.

- ↑ "Valcke denies 2022 'bought' claim". BBC News. 30 May 2011.

- 1 2 Booth, Robert. "Qatar World Cup construction 'will leave 4,000 migrant workers dead'". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Sepp Blatter: awarding 2022 World Cup to Qatar was a mistake | Football". theguardian.com. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ "Sepp Blatter admits summer World Cup in Qatar mistake – CBC Sports – Soccer". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ http://www.itv.com/news/2015-06-09/fifa-2022-world-cup-the-human-cost-in-qatar/

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (24 September 2013). "More than 500 Indian workers have died in Qatar since 2012, figures show | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33019838

- 1 2 Matthew Weaver. "Fifa to investigate arrest of BBC news team in Qatar". the Guardian.

- ↑ Rory Jones and Nicolas Parasie (4 June 2015). "Blatter's Resignation Raises Concerns About Qatar's FIFA World Cup Prospects". WSJ.

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3106899/The-squalid-conditions-building-Qatar-s-tainted-260-billion-World-Cup-4-000-predicted-die-tournament.html

- ↑ http://www.migrant-rights.org/2015/10/qatar-no-country-for-migrant-men/

- ↑ Wahl, Grant (18 February 2015), "Insider notes: Qatar set for winter World Cup, MLS CBA update, more", Planet Football, Sports Illustrated, retrieved 19 February 2015,

Multiple sources say it's a done deal that World Cup 2022 will take place in November and December of 2022 in Qatar. A FIFA task force will...make that recommendation, and the FIFA Executive Committee is set to make the decision final...next month.

- ↑ "World Cup 2022: Fifa task force to seek new dates for tournament". BBC Sport. 4 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ↑ "Late-November/late-December proposed for the 2022 FIFA World Cup". FIFA.com. 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "2022 World Cup: Qatar event set for November and December". BBC Sport. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Whether in June or November, Qatar's World Cup is about death and money". The Guardian. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar World Cup decision 'a blatant mistake' – RTÉ Sport". Rte.ie. 24 July 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Lutz, Tom (2013-09-17). "World Cup 2022: Australia wants Fifa compensation for failed bid". The Guardian.

- ↑ Peck, Tom (2014-02-24). "Premier League chief Richard Scudamore threatens to sue over November/December proposal". The Independent. London.

- ↑ "World Cup final 2022 one week before Christmas". Rte.ie. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ "Fresh corruption claims over Qatar World Cup bid". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Sports Illustrated, "Sorry Soccer", 23 May 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ FIFA tight-lipped over whistleblower. Al Jazeera. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Qatar World Cup whistleblower retracts her claims of Fifa bribes. The Guardian. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Watt, Holly (18 March 2014). "World Cup 2022 investigation: demands to strip Qatar of World Cup". The Telegrph. London. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ "Qatar 2022: Fifa sponsor demands 'appropriate investigation'". BBC Sport. 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Blitz, Roger (8 June 2014). "Big sponsors pile pressure on Fifa over Qatar World Cup". Financial Times. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Plot to buy the World Cup". The Sunday Times. 1 June 2014.

- ↑ Conway, Richard (5 June 2014). "BBC Sport – World Cup 2022: Qatari officials consider legal action". BBC.com. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "2022 World Cup bribery accusations denied by Qatar organizers – World – CBC News". Cbc.ca. 2 June 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "BBC Sport – Qatar 2022: Sepp Blatter says corruption claims are racist". BBC Sport.

- ↑ Owen Gibson. "Sepp Blatter launches broadside against the 'racist' British media". the Guardian. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ ABC News. "FIFA Officials Arrested Over Alleged 'Rampant, Systematic' $150M Bribery Scheme". ABC News. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ Withnall, Adam (7 June 2014). "Fifa corruption whistleblower says Qatar will be stripped of 2022 World Cup". London: The Independent.

- ↑ Hassett, Sebastian (28 October 2011). "SBS locks in two more World Cups". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Globo buys broadcast rights to 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups™". FIFA. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bell Media lands deal for FIFA soccer from 2015 through 2022". TSN. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ Myers, Sanjay (28 October 2011). "SportsMax lands long-term FIFA package". Jamaica BServer. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "EBU in European media rights deal with FIFA for 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups™" (Press release). European Broadcasting Union. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "BBC, ITV, ARD and ZDF sign World Cup TV deals". sportspromedia.com. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ Barros, Carlos. "RTP e Seleção Nacional até 2018". RTP.pt. Rádio e Televisão de Portugal. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Longman, Jeré (21 October 2011). "Fox and Telemundo Win U.S. Rights to World Cups". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FIFA World Cup 2022. |