Hamartia

The term hamartia derives from the Greek ἁμαρτία, from ἁμαρτάνειν hamartánein, which means "to miss the mark" or "to err".[1][2] It is most often associated with Greek tragedy, although it is also used in Christian theology.[3] Hamartia as it pertains to dramatic literature was first used by Aristotle in his Poetics. In tragedy, hamartia is commonly understood to refer to the protagonist’s error or flaw that leads to a chain of plot actions culminating in a reversal from their good fortune to bad. What qualifies as the error or flaw can include an error resulting from ignorance, an error of judgement, a flaw in character, or sin. The spectrum of meanings has invited debate among critics and scholars, and different interpretations among dramatists.

Hamartia in Aristotle’s Poetics

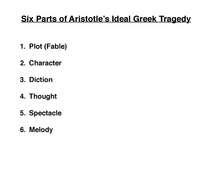

Hamartia is first described in the subject of literary criticism by Aristotle in his Poetics. The source of hamartia is at the juncture between Character and the character's actions or behaviors as outlined by Aristotle.

"Character in a play is that which reveals the moral purpose of the agents, i.e. the sort of thing they seek or avoid."[4]

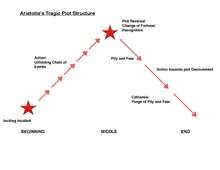

In his introduction to the S. H. Butcher translation of ″Poetics″, Francis Fergusson describes hamartia as the inner quality that initiates, in Dante's words, a ″movement of spirit″ within the protagonist to commit actions which drive the plot towards its tragic end, inspiring in the audience a build of pity and fear that leads to a purgation of those emotions, or Catharsis.[5][6]

Jules Brody, however, argues that "it is the height of irony that the idea of the tragic flaw should have had its origin in the Aristotelian notion of hamartia. Whatever this problematic word may be taken to mean, it has nothing to do with such ideas as fault, vice, guilt, moral deficiency, or the like. Hamartia is a morally neutral non-normative term, derived from the verb hamartano, meaning 'to miss the mark,' 'to fall short of an objective.' And by extension: to reach one destination rather than the intended one; to make a mistake, not in the sense of a moral failure, but in the nonjudgmental sense of taking one thing for another, taking something for its opposite. Hamartia may betoken an error of discernment due to ignorance, to the lack of an essential piece of information. Finally, hamartia may be viewed simply as an act which, for whatever reason, ends in failure rather than success."[7]

In Greek tragedy, for a story to be ″of adequate magnitude″ it involves characters of high rank, prestige, or good fortune. If the protagonist is too worthy of esteem, or too wicked, his/her change of fortune will not evoke the ideal proportion of pity and fear necessary for catharsis. Here Aristotle describes hamartia as the quality of a tragic hero that generates that optimal balance.

"...the character between these two extremes - that of a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty." [8]

Hamartia in Christian theology

Hamartia is also used in Christian theology because of its use in the Septuagint and New Testament. The Hebrew (chatá) and its Greek equivalent (àµaρtίa/hamartia) both mean "missing the mark" or "off the mark".[9] There are four basic usages for hamartia.

- Hamartia is sometimes employed to mean acts of sin "by omission or commission in thought and feeling or in speech and actions" as in Romans 5:12, "all have sinned".[10]

- Hamartia is sometimes applied to the fall of man from original righteousness that resulted in humanity's innate propensity for sin, that is original sin.[11] For example, as in Romans 3:9, everyone is "under the power of sin".[12]

- A third application concerns the "weakness of the flesh" and the free will to resist sinful acts. "The original inclination to sin in mankind comes from the weakness of the flesh."[13]

- Hamartia is sometimes "personified".[14] For example, Romans 6:20 speaks of being enslaved to hamartia (sin).

Tragic flaw, tragic error, and divine intervention

Aristotle mentions hamartia in Poetics. He argues that it is a powerful device to have a story begin with a rich and powerful hero, neither exceptionally virtuous nor villainous, who then falls into misfortune by a mistake or error (hamartia). Discussion among scholars centers mainly on the degree to which hamartia is defined as tragic flaw or tragic error.

Critical Argument for flaw

Poetic justice describes the obligation of the dramatic poet, along with philosophers and priests, to see that their work promotes moral behavior.[15] 18th century French dramatic style honored that obligation with the use of hamartia as a vice to be punished[16][17] Phèdre, Racine's adaptation of Euripides' Hippolytus, is an example of French Neoclassical use of hamartia as a means of punishing vice.[18][19]Jean Racine says in his Preface to Phèdre, as translated by R.C. Knight:

″The failings of love are treated as real failings. The passions are offered to view only to show all the ravage they create. And vice is everywhere painted in such hues, that its hideous face may be recognized and loathed.″ [20]

The play is a tragic story about a royal family. The main characters respective vices; rage, lust and envy lead them to their tragic downfall.[21]

Critical argument for error

In her 1963 Modern Language Review article, The Tragic Flaw: Is it a Tragic Error?, Isabel Hyde traces the twentieth century history of hamartia as tragic flaw, which she argues is an incorrect interpretation. Ms. Hyde draws upon the language in Butcher's interpretation of Poetics regarding hamartia as both error and ″defect in character.″ Hyde points out a footnote in which Butcher qualifies his second definition by saying it is not a ″natural″ expression to describe a flaw in behavior.[22] Hyde calls upon another description from A.C. Bradley's Shakespearean Tragedy of 1904 which she contends is misleading:

"...the comparatively innocent hero still shows some marked imperfection or defect, irresolution, precipitancy, pride, credulousness, excessive simplicity, excessive susceptibility to sexual emotion and the like...his weakness or defect is so intertwined with everything that is admirable in him..." [23]

Hyde goes on to elucidate interpretive pitfalls of treating hamartia as tragic flaw by tracing the tragic flaw argument through several examples from well-known tragedies including Hamlet and Oedipus the King. Hyde observes that students often cite ″thinking too much″ as Hamlet's tragic flaw upon which his demise in the story depends. That citation does not, however, offer explanation for the moments when Hamlet does act impulsively and violently. It also embarks down a trail of logic that suggests he ought to have murdered Claudius right away to avoid tragedy, which Hyde asserts is problematic. In Oedipus the King, she observes that regard of Oedipus' hasty behavior at the crossroads, or his trust in his intellect as the qualities upon which the change of fortune relies, is incomplete. Instead, to regard his ignorance of the true identity of his parents as the keystone to his downfall takes into account all of his decisions that lead to the tragic end. Rather than a flaw in character, error, in Oedipus' case based upon lack of information, is the more complete interpretation.

In his 1978 Classical World (journal) article Hamartia, Ate, and Oedipus, Leon Golden compares scholarship that examines where to place hamartia's definition along a spectrum connecting the moral, flaw, and the intellectual, error. His goal is to revisit the role, if any, Ate, or divine intervention, plays in hamartia. The Butcher translation of ″Poetics″ references hamartia as both a ″single great error″, and ″a single great defect in character″, prompting critics to raise arguments. Mid-twentieth century scholar Phillip W. Harsh sees hamartia as tragic flaw, observing that Oedipus assumes some moral ownership of his demise when he reacts excessively with rage and murder to the encounter at the crossroads.[24] Van Braam, on the other hand, notes of Oedipus' hamartia, ″no specific sin attaching to him as an individual, but the universally human one of blindly following the light of one's own intellect.″[25] He adds that a defining feature of tragedy is that the sufferer must be the agent of his own suffering by no conscious moral failing on his part in order to create a tragic irony. O. Hey's observations fall into this camp as well. He notes that the term refers to an action that is carried out in good moral faith by the protagonist, but as he has been deprived of key pieces of information, the action brings disastrous results.[26] J.M. Bremer then conducted a thorough study of hamartia in Greek thought, focusing on its usage in Aristotle and Homer. His findings lead him, like Hyde, to cite hamartia as an intellectual error rather than a moral failing.[27]

Critical arguments on divine intervention

J.M. Bremer and Dawe both conclude that the will of the gods may factor into Aristotelian hamartia. Golden disagrees.[28] Bremer observes that the Messenger in Oedipus Rex says, ″He was raging - one of the dark powers pointing the way, ...someone, something leading him on - he hurled at the twin doors and bending the bolts back out of their sockets, crashed through the chamber,″.[29] Bremer cites Sophocles' mention of Oedipus being possessed by ″dark powers″ as evidence of guidance from either divine or daemonic force. Dawe's argument centers around tragic dramatists' four areas from which a protagonist's demise can originate. The first is fate, the second is wrath of an angry god, the third comes from a human enemy, and the last is the protagonist's frailty or error. Dawe contends that the tragic dénouement can be the result of a divine plan as long as plot action begets plot action in accordance with Aristotle. Golden cites Van Braam's notion of Oedipus committing a tragic error by trusting his own intellect in spite of Tiresias' warning as the argument for human error over divine manipulation. Golden concludes that hamartia principally refers to a matter of intellect, although it may include elements of morality. What his study asserts is separate from hamartia, in a view that conflicts with Dawe's and Bremer's, is the concept of divine retribution.[30]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Hamartia". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Hamartia: (Ancient Greek: ἁμαρτία) Error of Judgement or Tragic Flaw. ″Hamartia″. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Cooper, Eugene J. ″Sarx and Sin in Pauline Theology″ Laval théologique et philosophique. 29.3 (1973) 243–255. Web. Érudit. 1 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Aristotle. "Poetics". Trans. Ingram Bywater. The Project Gutenberg EBook. Oxford: Clarendon P, 2 May 2009. Web. 26 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ Fergusson 8

- ↑ The Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

- ↑ Jules Brody, "Fate, Philology, Freud," Philosophy and Literature 38.1 (April 2014): 23.

- ↑ Aristotle. "Poetics". Trans. Ingram Bywater. The Project Gutenberg EBook. Oxford: Clarendon P, 2 May 2009. Web. 26 Oct. 2014.

- ↑ http://www.blbclassic.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H2398&t=KJV, http://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?strongs=G266, and http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/miss+the+mark

- ↑ Thayer, J. H. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Harper, 1887), s.v. ?µa?t?a online at https://books.google.com/books?id=1E4VAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thayer++Greek-English&hl=en&sa=X&ei=EsAdVdiLBM6uogSsn4LADw&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Thayer%20%20Greek-English&f=false.

- ↑ Cooper, Eugene "Sarx and Sin in Pauline Theology" in Laval théologique et philosophique. 29.3 (1973) 243-255. Web. Érudit. 1 Nov 2014 and

Thayer, J. H. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Harper, 1887), s.v. ?µa?t?a online at https://books.google.com/books?id=1E4VAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thayer++Greek-English&hl=en&sa=X&ei=EsAdVdiLBM6uogSsn4LADw&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Thayer%20%20Greek-English&f=false. - ↑ http://biblehub.com/romans/3-9.htm

- ↑ Edward Stillingfleet, Fifty Sermons Preached upon Several Occasions (J. Heptinstall for Henry Mortlock, 1707), 525. Online at https://books.google.com/books?id=kSVWAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22weakness+of+the+flesh%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Abridged in One Volume (Eerdmans, 1985), 48.

- ↑ Burnley Jones and Nicol, 125

- ↑ Burnley Jones and Nicol,12,125

- ↑ Thomas Rymer. (2014). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/514581/Thomas-Rymer

- ↑ Worthen, B. The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama 5th ed. 444-463. Boston: Thomson Wadsworth. 2007. Print.

- ↑ Racine, Jean. Phèdre, Harvard Classics, Vol. 26, Part 3. Web. 11 Dec. 2014. http://www.bartleby.com/26/3/

- ↑ Worthen,446

- ↑ Euripedes. Hippolytus, Harvard Classics, 8.7. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. http://www.bartleby.com/8/7/

- ↑ Butcher, Samuel H., Aristotle’s Theory of Poetry and Fine Art, New York 41911

- ↑ Bradley, A. C. 1851-1935. Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures On Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. London: Macmillan and co., limited, 1904. Web, 13 Dec. 2014. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000240890;view=1up;seq=1

- ↑ Golden, Leon. ″Hamartia, Ate, and Oedipus″. The Classical World, 72.1 (Sep., 1978), 3-12. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4348969

- ↑ P. van Braam, ″Aristotle's Use of Ἁμαρτία″ The Classical Quarterly, 6.4 (Oct., 1912), 266-272. London: Cambridge UP. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/635946

- ↑ Hey, O. ″ἁμαρτία Zur Bedeutungsgeschichte des Wortes″ Philologus 83 1-15, (1928). Web. 7 Dec. 2014.

- ↑ Bremer, J.M. "Hamartia." Tragic Error in the Poetics of Aristotle and in Greek Tragedy. Amsterdam, Adolf M. Hakkert, 1969.

- ↑ Golden, 6

- ↑ Worthen, 85

- ↑ Golden, 10

References

- Bremer, J.M. "Hamartia." Tragic Error in the Poetics of Aristotle and in Greek Tragedy. Amsterdam, Adolf M. Hakkert, 1969.

- Cairns, D. L. Tragedy and Archaic Greek Thought. Swansea, The Classical Press of Wales, 2013.

- Dawe, R D. "Some Reflections on Ate and Hamartia." Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 72 (1968): 89-123. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Hyde, Isabel. "The Tragic Flaw: is It a Tragic Error?" The Modern Language Review 58.3 (1963): 321-325. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Moles, J L. "Aristotle and Dido's 'Hamartia'" Greece & Rome, Second Series 31.1 (1984): 48-54. JSTOR. St. Louis University Library, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Stinton, T. C. W. "Hamartia in Aristotle and Greek Tragedy" The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Dec., 1975): 221 - 254. JSTOR. St. Louis University, St. Louis. 29 Apr. 2008.

- Golden, Leon, "Hamartia, Ate, and Oedipus", Classical World, Vol. 72, No. 1 (Sep., 1978), pp. 3–12.

- Hugh Lloyd-Jones, The Justice of Zeus, University of California Press, 1971, p. 212.